Walter Greenwood is well-known for his novel Love on the Dole (1933), which is remembered as the iconic British novel of the Depression. By 1940 it had sold some 46, 290 copies in the UK, and had been seen in a stage adaptation by some 3 million people in Britain. Love on the Dole was often regarded as authentic testimony from a working-class author who had experienced unemployment in Salford between 1929 and 1933. Indeed it was unemployment (and the typewriter which he removed from his last place of employment in lieu of wages) which gave him the opportunity to write (see Geenwood’s memoir, There Was a Time, 1967. p.199). However, he did not begin by writing a novel, but by writing short stories about working-class life intended for fiction magazines. However, only one of these stories was accepted (‘A Maker of Books’), earning him twenty-five guineas in 1931, enough, he said, to live on for six months (There Was a Time, p.215). When Greenwood wrote to the successful popular novelist Ethel Mannin for help, she advised him to turn the short stories into a novel if he wished to make a living as a writer. This he did, reworking the stories to produce Love on the Dole in 1933.

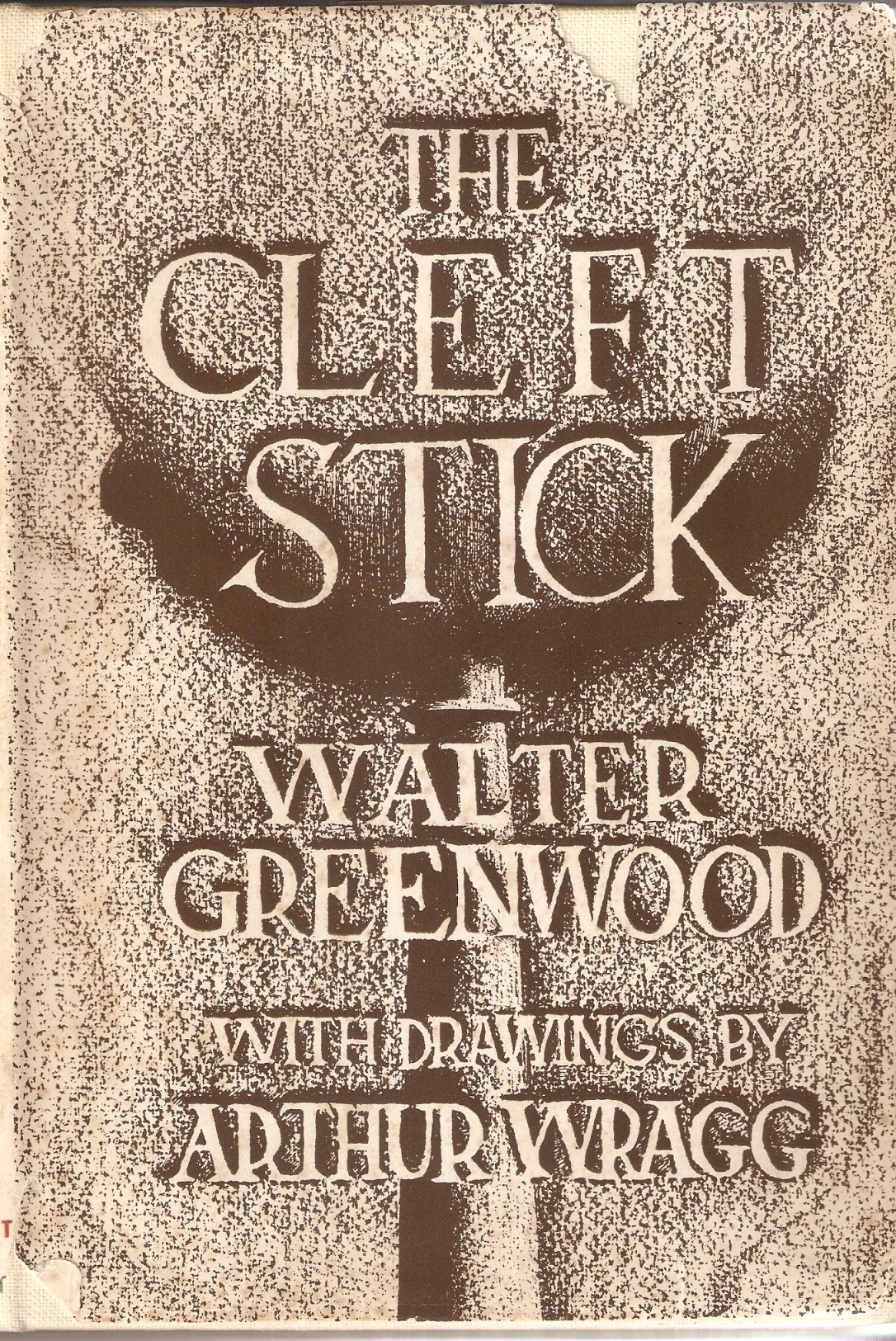

It was not until 1937 that Greenwood published the original short stories in a form very different from that he first planned. They appeared in a lavish edition called The Cleft Stick which was a co-produced work with the artist Arthur Wragg (a graduate of Sheffield School of Art who was also, like Greenwood, from a poor background). The book included full-page illustrations, illustrated end-papers and an embossed cover as well as an illustrated dust-wrapper. By this time both Greenwood and Wragg had a certain celebrity status as working-class writers, and the book sold well. Arthur Wragg had published a number of illustrated works, often with highly original and strikingly contemporary versions of Christian themes. These included the controversial Psalms for Modern Life in 1933, which juxtaposed the texts of the psalms with his stark black and white drawings of contemporary life and Jesus Wept of 1934, either of which might have attracted Greenwood’s attention for their illustrations of the unemployment, poverty and dereliction of thirties Britain. The Cleft Stick has been extraordinarily neglected, yet it was favourably reviewed as a controversial sequel to Love on the Dole, and was widely read in Britain and the USA (there are still quite a few copies available second-hand at a certain price, but it would be excellent if the volume were re-printed).

If Love on the Dole was the most celebrated book about British working-class life in the thirties, The Cleft Stick was not that far behind, and it also kept Greenwood and his reputation in the news, as well as extending his celebrity by associating him with the artist Arthur Wragg, who was equally newsworthy. Many reviewers thought that The Cleft Stick showed considerable development, giving an even more pessimistic vision of British working-class life than did Love on the Dole. Indeed, The Cleft Stick is not even just another work of working-class fiction by the author of Love on the Dole: it is in fact a text which is intimately connected to Love on the Dole, for which it may be seen as either a prequel or sequel or even as the original version of what became Love on the Dole. If we are interested in Love on the Dole and working-class writing we certainly should be interested in The Cleft Stick too.

In their adverts the publishers, Selwyn and Blount, drew attention to Greenwood and Wragg’s joint work with the underlined heading, ‘A Brilliant Collaboration.’ They also quoted from a review in the south Wales newspaper, the Western Mail which emphasised the co-operative nature of the work: ‘Remarkable for the grim power and stark reality of the stories, and for the tremendously gripping drawings’.(in the Sunday Times, 21 November, 1937, p. 11). In a follow-up advert (11December) the publishers quoted what may seem (even to Greenwood fans) like extravagant praise from Edith Sitwell, stating that The Cleft Stick is ‘A wonderful book. It contains two of the greatest short stories that have been produced in a hundred years – I don’t mean in England, I mean in the world. Arthur Wragg is an enrichment of one’s life.’ Some reviews discussed only Greenwood’s texts, but most saw drawings and stories as equal contributions.

In his ‘Author’s Preface’ to The Cleft Stick Greenwood includes this account of the striking book’s origins and the leading role of Wragg:

Editors of popular magazines, whom I considered ought to have been proud to have included these stories in their pages, thought differently, though all were generous in their praise, one of them actually paying twenty-five guineas for the privilege of printing one. I was invited to write football stories, but, not having any feeling for such subjects, the effort would have been a waste of time.

Miss Ethel Mannin, a complete stranger to me at the time, was good enough to read the collection and to advise me to write a novel using some of the characters. I followed her advice, and Love on the Dole was the consequence.

Had it not been for a holiday in Cornwall last year when I spent a good deal of time in the company of my friend Arthur Wragg, the artist, I guess the short stories comprising most of this volume would still be in their brown-paper parcel (p.9).

In form The Cleft Stick is a two-hundred-and-twenty-page collection of fifteen short stories, accompanied by sixteen illustrations, of which twelve are full double-page images and four are full single page images. Thus each story has one accompanying illustration, apart from the final one, ‘The Old School’, which has two, though it is not strictly a story, since it is sub-titled ‘an autobiographical fragment’ (p. 212). There is also the three-page ‘Author’s Preface’. Of the fifteen short stories, twelve date to the period of unemployment when Greenwood first started writing — that is from 1928 to1931 — while the autobiographical fragment was first published in Graham Greene’s anthology The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape) in 1935. The two remaining stories, ‘Patriotism’ and ‘Any Bread, Cake or Pie?’, Greenwood tells us in his Preface (p.9), ‘are of recent vintage’ and are thus clearly written after Love on the Dole (1933). Wragg’s images were completely new pieces of work responding in his own unique style to Greenwood’s stories.

A number of the characters in Love on the Dole are shared by The Cleft Stick and some are portrayed in Wragg’s illustrations. Thus Ted Munter (pictured above by Wragg, on the thresh-hold of starting his own book-making venture), Sam Grundy’s side-kick in the novel, is the protagonist of the first story, ‘A Maker of Books’, while the Scodger family, minor characters in the novel, have a whole story to themselves in ‘Mrs Scodger’s Husband’. The title story, ‘The Cleft Stick’ gives a more complete account of the awful life of Mrs Cranford, whose story is told in passing in the novel, and the final end of Blind Joe Riley, who opens and closes the novel in his job as a human alarm-clock or ‘knocker-up, is told in ‘Joe Goes Home’. Ned Narkey, one of the villains of the novel, appears as an even more villainous exploiter of women in ‘The Son of Mars’, while two of the novel’s chorus of older women, Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle are joined in ‘The Practised Hand’ by a third much less scrupulous and indeed murderous older woman who is not included in the novel at all, Mrs Haddock (Mrs Bull makes an appearance alone in ‘The Cleft Stick’). The character of Harry in ‘Any Bread, Cake or Pie?’ may bear some resemblance to Harry Hardcastle as a boy in the novel. A number of stories and their characters have no real equivalent in the novel, including two about small shops and businesses in Hanky Park. The shops might suggest the possibility of individual success and social mobility – and that would not fit with the overall theme of Love on the Dole which sees no way out of Hanky Park for most (except death). The two small-business stories are ‘The Little Gold Mine’ (which greatly expands a reference in the novel to Mr Hulkington’s grocery shop) and ‘ “All’s Well That Ends Well” ’ (which tells the story of ‘Babson’s High-Class Supper Bars’, a successful business which does not make it into Love on the Dole in any form). It should also be noted that two key figures in the novel have little direct equivalent in the short story collection: Larry Meath, the working-class intellectual and activist has no story, and there is no direct equivalent for Sally Hardcastle, the working-class woman who makes a desperate and appalling deal with the bookie Sam Grundy for the benefit of her male relatives and mother.

‘The Cleft Stick’ was in fact the second story which Greenwood wrote, as he recalled in an interview in the nineteen-seventies, and was originally called by the more literal title of ‘Jack Cranford’s Wife’ (‘Dole Cue’: interview with Catherine Stott, the Guardian, 2 April, 1971, p. 10). It is about the desperation of Mrs Cranford, who has too many children and not enough money: she decides to put her head in the gas-oven and end it all – but is defeated by not having a penny for the gas-meter – she is in the cleft stick. Though he did not place the story first in The Cleft Stick, Greenwood (and presumably Wragg) clearly felt that its mood and title summed up the atmosphere of the whole collection. There was not so much working-class writing published in the nineteen thirties that we can afford totally to forget such a once well-known and aesthetically interesting collaboration between a successful working-class writer and successful working-class artist.

Chris Hopkins

PS for another review of The Cleft Stick, see Sylvia D’s on the Reading 1900-1950 site: Another Cleft Stick Review