Love on the Dole made Deborah Kerr into a star, and her achievement in the film was noted by a number of newspaper reviews in 1941, including one by James Agate in the Tatler (11/6/1941, p.6). However, a recent BFI book on Deborah Kerr by Sarah Street notes that a significant article in Picture Post predicted in December 1940, even before its release, that Love on the Dole would make her name (Vo. 9, number 10, 7 December 1940, pp. 18-19). I was not aware of this feature before and am grateful to have had it drawn to my attention. Picture Post only launched in 1938 but quickly became very popular, using in this case its novel photojournalistic approach to do its best to ensure that its prediction would come true, putting Deborah Kerr on the front cover and printing a lavish double-page photospread, accompanied by snappy captions and a concise article about her career so far (1) This article will explore how Picture Post presented and made the case for their future star. It is probably useful to read it in conjunction with my article on Deborah Kerr as an unusual kind of star in her (almost) debut appearance in Love on the Dole: Deborah Kerr, Stardom, and Love on the Dole – Walter Greenwood: Not Just Love on the Dole (waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com)

The magazine’s treatment of Deborah Kerr, both on the cover and in the article, is in many ways in accordance with the director John Baxter and the author Walter Greenwood’s view that she was perfect for the part of Sally Hardcastle because she did not bring with her a star persona, but had a strongly ordinary quality. Picture Post also brings in some testimony which asserts to her exceptional and star-like beauty, so it perhaps has things both ways: Deborah Kerr is the extraordinary-ordinary woman. Here are the photographs which make up the majority of the feature in the order in which they are presented in the magazine (all photographed from a copy of Picture Post in the author’s collection – the front cover is missing though, which is why I needed the assistance of Alamy for that image!). All the captions are the original Picture Post ones – my own commentary on the images comes after all the photographs.

She is talked of as the new star of British films, but there is nothing luxurious about the way she lives. At present she is working at Elstree and lives in a tiny room. She makes breakfast for herself when she gets up.

She has acted in films before. She has acted on the stage with a repertory company. For a time she learned ballet. Her album recalls those other days. She shows it while they are waiting to go on the film set.

Deborah Kerr is called by her discoverers a ‘Botticelli blonde’. She has reddish hair and blue eyes. Now she makes up for her film work.

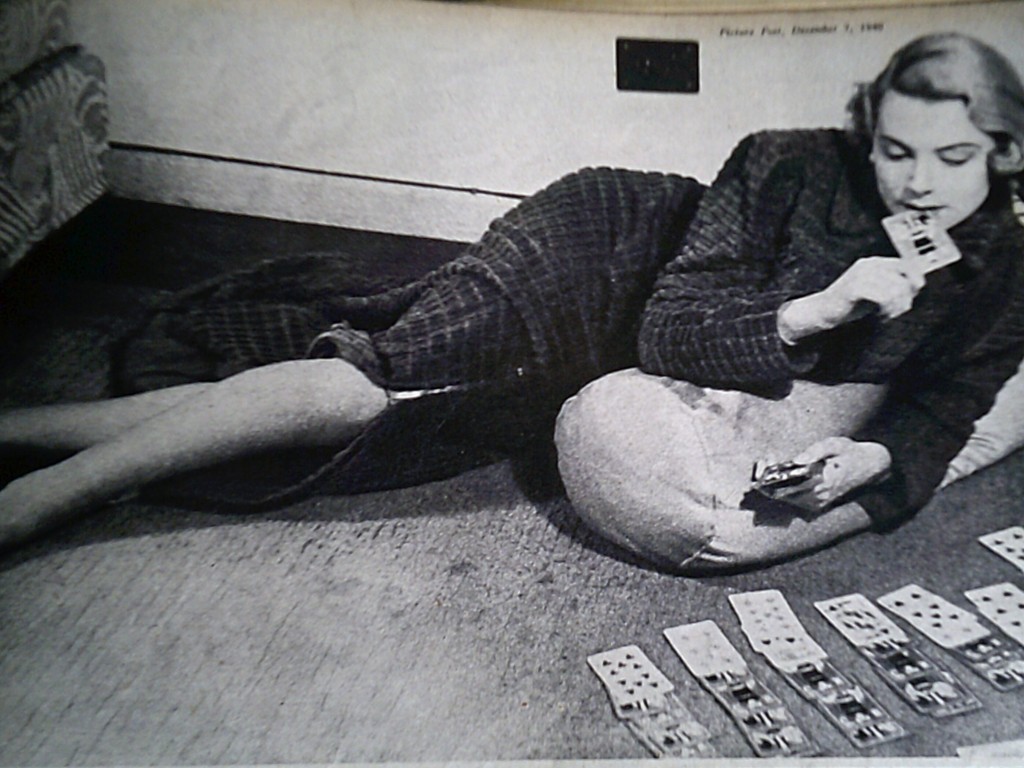

Deborah Kerr works hard at Elstree all week. Her recreation is a game of patience. At week-ends she takes her dog to the country – to see more dogs.

‘Love on the Dole’ was a great success on the stage. London flocked to find out about unemployment. Now they are making a film of it. Deborah Kerr plays the girl who goes off with the bookmaker. The author, Walter Greenwood, reads over her part with her.

The cover itself seems to want to present Kerr as ordinary and perhaps ‘homely’, showing her quite unexceptional tweed jacket and stressing her fondness for her dog (and perhaps suggesting she is not at present particularly participating in a social world populated by other stars). This is reinforced by the caption to the fourth photograph of Kerr which shows her playing patience, where the text represents her as living when not working in a positively dog-centric personal world!

The first photograph reinforces the ‘ordinary girl’ theme by showing Kerr doing an everyday activity – boiling the kettle in the morning and getting her own breakfast – while the caption makes this ordinariness very explicit, and stresses that she lives in a single small room. Though we are used to current magazines doing the ‘ordinary girl’ treatment on celebrities, and while Picture Post is undoubtedly strongly representing the actress in a certain and overtly thematised way, there is also a basis in truth to the modest lifestyle claim at this point, since Kerr when cast in Love on the Dole could only afford to live in London in a room at a YWCA hostel. One aspect of the image which may strike the viewer as slightly less ordinary is the garment Deborah Kerr is wearing to make her breakfast, which looks very carefully cut, with a snazzy and presumably colourful pattern, and entirely elegant and fashionable. Is this really what an ordinary women threw on first thing in the morning in the early forties? The answer is that this is an interestingly ambiguous garment which in itself may add another level of reinforcement to the ordinary/extraordinary theme. The item is a ‘house-coat’, something which was usually made of printed cotton, was often stylishly cut, and yet was said by some to be intended to be worn for doing house-work. I am grateful to Christine Boydell’s excellent essay on the house-coat in her Festival of Pattern site for clarifying my thinking on this (‘At Home Glamour’: explaining the housecoat to consumers in mid-twentieth century Britain. | Festival of Pattern (wordpress.com). She explains that the ‘house-coat’ from the thirties to the fifties was indeed ‘a contradictory item of clothing’:

It was an elegant, tailored, full-length and often voluminous indoor outfit which has no equivalent today. Its meaning and purpose were contested and there was disagreement about what it was for, and when it should be worn: was it a more glamorous cousin of the dressing gown; was it suitable for wearing to dinner parties; was it practical for household duties; could one answer the front door wearing one?

Again while this image stresses Kerr’s ordinariness, it also shows her as capable of stylishness in the most domestic of circumstances.

The second photograph focuses again on her ordinariness, and also on her relative inexperience in the world of acting. She only has a brief professional history (though it has some variety) and it is recorded in that then common repository for memories, her photograph album. The other person in this photo who she is sharing her memories with is the actress Mary Merrall, who played Mrs Hardcastle in the film of Love on the Dole. Merrall had first appeared on stage in 1907, though she was a newcomer to film herself (see: Mary Merrall – Wikipedia). She appears in this image as a motherly figure perhaps, echoing her role in Greenwood’s story, and suggesting a down-to-earth and kind mentoring relationship with her younger colleague. The image is redolent of a homely atmosphere on set and of the modesty of an actress who has just been given a key role.

The third photograph shows us behind the scenes as she is made-up ready for camera, but she does not look like a pampered star, wearing what is clearly her own dressing-gown, as in the fourth photograph, and doing her own nails (I have not been able to identify the make-up artist). However, here the caption adds in an element of the ‘extraordinary’ by referring to those who have seen her as a ‘Botticelli blonde’. This idea is stated more fully in the Picture Post article itself and was the idea of Nicholas Davenport, the financial director of Capitol Film Productions and a stockbroker who acted as a financial adviser to Gabriel Pascal. Pascal was the director of the film of Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara, in which Kerr acted the Salvation Army soldier, Jenny Hill, in 1940, just before Love on the Dole was filmed. The article quotes Davenport as saying that her face: ‘impressed me . . . because of its profile resemblance to the woman in Botticelli’s Purification of the Leper‘. This painting is part of Botticelli’s three frescoes which make up his Temptations of Christ in the Sistine Chapel, Rome (painted 1480-82). I think the female figure referred to by Davenport is the woman in profile with reddish-blond hair in the middle-ground on the left of the scene, standing behind the seated men who are closest to the high-priest and the cured leper. Kerr does indeed bear some resemblance to this subject of Botticelli’s- see below or the larger image from the Wikipedia entry on the painting: File:05 Tentaciones de Cristo (Botticelli).jpg – Wikimedia Commons . Davenport’s comment also of course associated Deborah Kerr with high art, adding cultural status to her image. (2)

The fourth photograph shows her at leisure, again in her dressing gown, playing patience, which might perhaps suggest self-reliance and independence. Finally, the fifth photograph shows her during rehearsal, with Walter Greenwood (in an image not widely known among Greenwood / Love on the Dole scholars). She looks serious and is clearly concentrating on the work in progress. She is in her costume of raincoat, hat and scarf, a costume which signifies her ordinary social status in the story: she is presentable and not wearing the older-fashioned shawl which the film shows many of the other mill-girls as wearing, but is not dressed any more opulently than other young women who work for a living, and who might indeed go to the cinema. This mode of dress is in the film eventually contrasted with the more showy clothing provided by Sam Grundy, and which includes a fox fur.

The article itself in fact only overlaps with the photograph captions on the issue of Botticelli, though in a way which suggests that Kerr herself is not keen on this construction of her persona. The article opens by suggesting that this is not a good time for an emerging star, when the ‘British film industry is pretty far down in the dumps’, but nevertheless says there are still films in production and that ‘a pretty girl is still noticed by the men who make these films’ (oh dear – exactly the power structure and male-gaze assumptions we might expect of the period- but Kerr gets in a riposte later). There then follows Nicholas Davenport’s view quoted above that Kerr has a ‘Botticelli blonde’ profile which constitutes a ‘new type of face on screen’. After that is a brief biography of Kerr so far, beginning inaccurately with the death of her father of wounds ‘soon after the last war’ (he in fact died in 1937, though this may have been a consequence of an infection to the stump of the leg amputated after the battle of the Somme in 1916). (3). It continues with her false start as a ballet student, her brief drama training and repertory theatre experience, and her first film casting in Contrabrand (director Michael Powell, British National Films, April 1940 – but in fact her cigarette-girl scenes were all cut before release). (4) Then comes the story of how Gabriel Pascal cast her in the relatively small but important role of the Salvation Army soldier, Jenny Hill, in his Shaw film, Major Barbara (Gabriel Pascal Productions, August 1941). However, Kerr also has a chance here to express her dislike of female appearance as the main basis of publicity and casting:

Nothing distresses her more than publicity which harps on ‘glamour’. ‘Just because I’m blonde everybody types me’, she grumbles. ‘I like playing parts with guts’.

The final paragraph deals with Love on the Dole and sums up what the article concludes are Deborah Kerr’s distinctive characteristics:

Whether Miss Kerr was at home as a Salvation Army Lassie must be judged from the film. But now she certainly has her chance as the girl who comforts the rich bookmaker in Love on the Dole [one of the oddest descriptions I have read of what happens in the story].

She is a lovely girl. She is crystal fresh in quality. She has intelligence, and that uncommon quality of common sense which endears the best young American actresses to the world’s audiences’.

Sarah Street argues that this Picture Post feature had a quite long-lasting effect on the development of Kerr’s film career:

The early years of her career were fundamentally important in establishing an expectation of future excellence on screen, prompted by her looks, which Picture Post likened to a ‘Botticelli blonde’ with ‘reddish gold hair, light blue eyes and face capable of expressing spiritual wistfulness.’ As a star subsequently identified with significant British colour films, this typage informed appreciations that connected her physiological attributes to a performance style and ethos that was considered to be graceful, marked by an assured physical stature that was ‘ladylike’ yet , at the same time, easily adaptable to playing assertive, distinctive characters (5)

Love on the Dole was not, of course, a colour film, though Sally Hardcastle’s blonde hair is visible in black and white (and in contrast to all the stage Sallies, including Wendy Hiller and Ruth Dunning, who played her as a brunette), but Deborah Kerr’s capacity to be ‘ladylike’ and assertive were certainly brought into play. Perhaps of even more immediate importance though were her ambiguous qualities as ordinary/ extraordinary – characteristics which the Picture Post article overtly thematised, while also sometimes falling into perhaps unintended contradictions. The feature undoubtedly did its utmost to soften up a potential audience for a new star, and perhaps a new kind of star. It may have played its part too therefore in helping make a mainly serious and partly grim film about past British social and economic failure into a notable success, even in the other and freshly grim circumstances of the early war years.

NOTES

Note 1. Sarah Street, Deborah Kerr, BFI/ Bloomsbury, 2018, p.11.

Note 2. Kerr became good friends with Davenport and his wife and records that she learnt a great deal about art and culture from them – see Deborah Kerr by Eric Braun (W.H. Allen, London, 1977) pp.50-1.

Note 3. See Eric Braun, Deborah Kerr, pp. 18 and 31-2.

Note 4. See Eric Braun, Deborah Kerr, pp. 43-4.

Note 5. Sarah Street, Deborah Kerr, BFI/ Bloomsbury, 2018, p. 11.