From the publication of Love on the Dole in 1933 onwards, Greenwood carefully kept press-cuttings books in which he pasted reviews of his work and other relevant press articles about his life or events he was involved in. These valuable documents are now in the Walter Greenwood Collection in the University of Salford Archives, catalogued as WGC/3/1, WGC/3/2 and WGC/3/3. (1) Greenwood chose to use in all three cases a large format Walker’s CENTURY Scrap and Newscutting Book no. 55. He was not alone in this choice – several archives hold scrapbooks from the same manufacturer compiled by public figures, such as one put together to record her ‘National Kitchen’ activity during the first world war by Florence Horsburgh (1889-1969), who later became one of the first female Conservative MPs, representing Dundee from 1931 until 1945, and Manchester Moss Side from 1951 to 1959. A recent post on the History Association website on possible approaches to scrapbooks as primary sources quotes from some of Walker’s promotional material to suggest that this scrapbook was a rather upmarket or at least ‘literary’ choice, being intended for ‘authors, clergymen, students and All Literary men’ (capitalisation and unthinking sexism as in the original!; 2).

Greenwood’s earliest clippings may have been gathered by the author himself, but the majority (from 1936 onwards according to the Walter Greenwood online catalogue description) were harvested by the Durrant’s Press Cuttings Agency, which attached each clipping to a standard printed label on which the publication source and date were added either in type or handwritten in ink (though sometimes one or the other piece of information is missing, and in addition sometimes page numbers are not included in the clipped portion). Clippings sent to Greenwood are mainly from a wide range of British newspapers, but also include a number of clippings from US papers referring to American editions of his work and the Broadway production of the play of Love on the Dole in 1936.

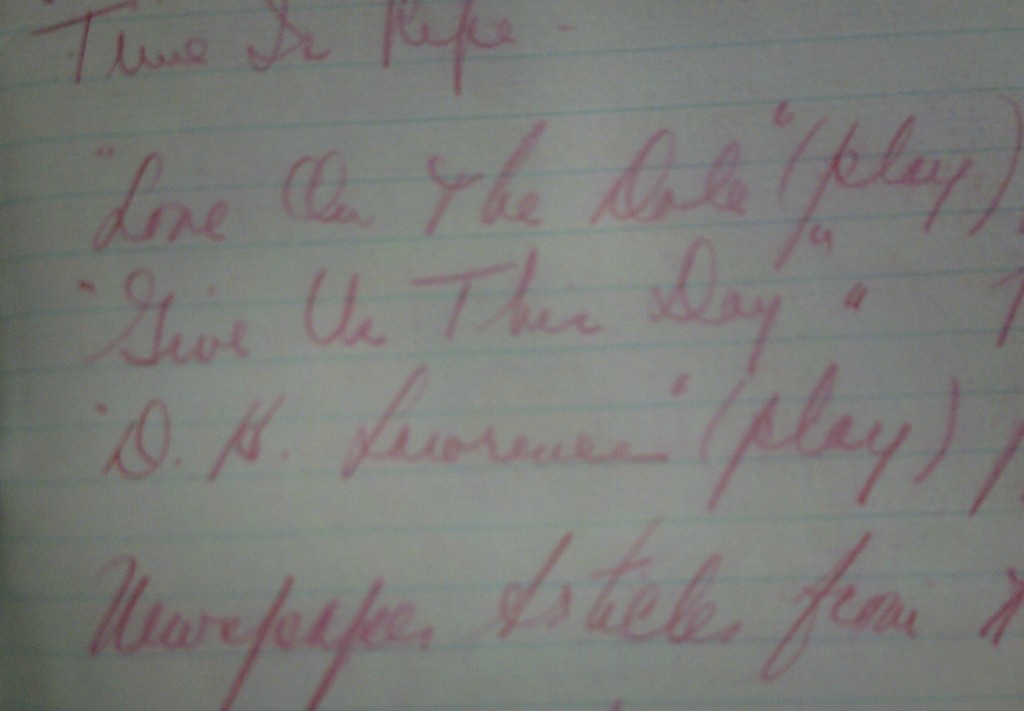

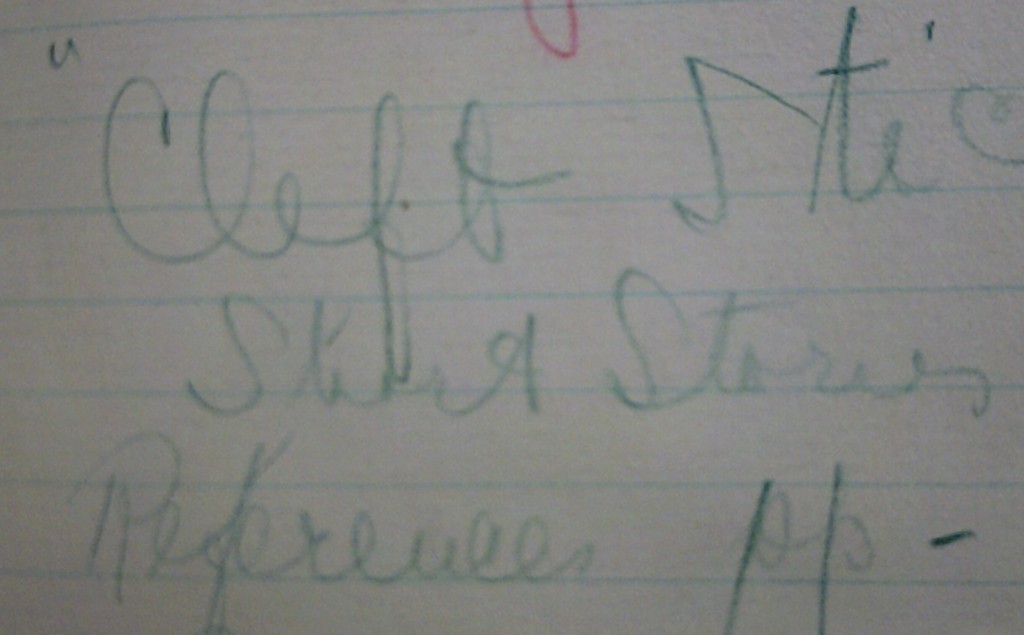

Presumably Durrant’s sent clippings at regular intervals and likewise Greenwood regularly pasted them into his Walker’s CENTURY Scrap and Newscutting Book. He also made use of the opening pages which were prepared with alphabetically-labelled index pages so that users could list the contents and page numbers of their personally selected cuttings. These contents pages are completed in Greenwood’s very recognisable hand in all three volumes, written sometimes in red pencil and sometimes in green.

The Press Cuttings Books are rich resources for researchers working on Greenwood’s work, reception, and life. While newspaper databases have transformed how research can be done across multiple newspapers and periodicals using search terms and parameters, not all newspapers from Greenwood’s time have as yet been digitalised, and his Press Cuttings Books certainly contain reviews which are not currently available in databases. Beyond that though, these scrapbooks also constitute Greenwood’s curation of his own career, using the technologies then available – a cuttings agency, a scrapbook, scissors, paste, and coloured pencils! As the scrapbook historian Cherish Watton suggests, scrapbooks are a kind of self-fashioning, and may ‘have a deliberate eye to legacy making’ (see Note 2). Watton has studied examples in which very varied kinds of material are pasted in next to each other: ‘in what other historical source could you find a newspaper clipping next to a cigarette butt; photographs next to leaves, and letters next to leaflets?’ (see Note 2).

This is not in fact wholly applicable to Greenwood’s ‘scrapbooks’, which actually concentrate entirely on Walker’s second-named function of ‘Newscutting Book’, and in that sense he made more restricted selections of material, using only press-cuttings, though of several genres. The majority of his clippings are reviews of his printed or performed works, but he also included interviews he gave, other biographical pieces, letters he had written to the press (and sometimes references to responses), and a number of short stories which he also published in newspapers between 1934 and 1951. No doubt there were practical aspects to this – in the pre-digital age such information was not very easy to find again after publication day, except by laborious searching in the few hard-copy newspaper libraries. Indeed, other writers certainly kept extensive collections of press-cuttings no doubt for both practical and personal reasons, including Greenwood’s Yorkshire near contemporary J.B. Priestley. (3)

However, I think what we mainly see in Greenwood’s consistent care with his clippings over a period of four decades is a sense of pride not only in having become a writer, but in sustaining that professional and vocational identity over a long period. Looking back from the vantage-point of 1967, Greenwood described in his memoir There was a Time (Cape, 1967) what must have seemed the fantastic ambition to transform himself from an unemployed manual or clerical worker on long-term low wages even when employed into a man who earned his living as a writer. Though the memoir focuses as much on Greenwood’s family and neighbours as on himself, there is one central personal narrative about becoming a writer, with alternating failures and successes along the way, bought back to life in a series of dramatic moments leading to a climactic conclusion. His inspiration to write one of his first stories by the example of his fellow-worker Sandy’s attempted (and failed) escape through becoming a successful ‘bookie’, shows Greenwood’s sense of how big a gamble it was to seek to get out of Hanky Park through writing, yet against the odds he did make it:

Messrs Batterby [a large draper], in company with other firms which felt the draught of the contraction of commerce, merged some of their departments, and those of us who were declared surplus to requirement exchanged our status as Gentlemen [that is their alleged professional identity as shop assistants] for membership of the growing brotherhood of the dole . . . This severe cut in income meant retrenchment for us at home . . . [but] there was . . . the ambition I had been nursing quietly for some time, to try my hand at earning a living from writing. (pp.184-5).

Out of nowhere came the recollection of Sandy Sinclair and his consuming hatred of the Motor Works’ factory environment . . . In his way was he not like me basically, in pursuit of the same thing, searching, like so many, for a way out of intolerable conditions? His desire was to make a book [i.e. set up as a then illegal on-street bookie], mine to write one. ‘A Maker of Books.’ There’s the title, anyway. All that I had to do now was to write the story. (p. 205).

The postman was approaching our door. Would he? Wouldn’t he? He stopped, rapped twice, flicked a letter through the open door, then passed on. I excused myself, resisted the temptation to sprint and strolled across. The letter was headed The Storyteller Magazine and was signed by ‘The Editor’. I read ‘. . . and would like to have your story ‘A Maker of Books’ for publication and offer twenty-five guineas for the first British serial rights . . . (p. 214).

‘Dear Sir,

We have read your novel with great interest. Unfortunately our Spring List is to include a book on a similar theme translated from the German, Mr Hans Fallada’s Little Man, What Now . . .’ (pp.248-9).

‘Dear Sir, We will publish your novel . . .

I was on the threshold of a wonderful year, though this I did not know. (p. 249)

It seems to me that when Greenwood bought his first Walker’s CENTURY Scrapbook & Newscutting Book No.55 in 1933, he was intent on reflecting back to himself in a concrete record that he had achieved his ambition of becoming recognised in the profession of writer, and of thereby wonderfully lifting himself, and perhaps his sister and mother too, out of long-term poverty, while at the same time arguing through his fiction and non-fiction against the conditions which produced and reproduced such conditions. In an interview for the Radio Times in 1971, Greenwood talked to the journalist George Rosie about the lasting consequences of his early poverty:

Old habits die hard, especially those formed by want. And most of Walter Greenwood’s habits were formed by poverty, despite the money and success that came his way after 1933, when his classic of the Depression era Love on the Dole was published. ‘I can’t get rid of that feeling of insecurity,’ he admits. ‘The fear that somehow it is all going to be taken away.’ Which is why he always pays his income tax in advance and will buy nothing unless he can pay cash. (4)

I think that perhaps every time Greenwood pasted another clipping into his Newscuttings Book he confirmed to himself that he was not going back to all that, that he continued to be a writer, the identity which had rescued him, and which he deployed to try to rescue others from the conditions imposed on those from his kind of working-class background.

Note 1. See Walter Greenwood Collection catalogue online: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/salforduniversity/data/gb427-wgc/wgc/3 . There are at the close of volume 3, a number of obituaries of Greenwood, presumably added by a family member in 1974. One from the Manchester Evening News is headlined simply: ‘Love on the Dole Greenwood is Dead’ (14 September, 1974, p. 5).

Note 2. See the useful post ‘Using Scrapbooks as Historical Sources’ by Cherish Watton, 16 December 2019 (https://historyjournal.org.uk/2019/12/16/using-scrapbooks-as-historical-sources) and the online exhibition featuring Horsburgh’ Walker’s CENTURY Scrapbook & Newscutting Book on the Churchill College Archives Centre: https://archives.chu.cam.ac.uk/collections/research-guides/hsbr/ . I am not completely certain from the reference exactly where the quotation from Walker’s promotional material comes from – it may be on the scrapbook itself.

Note 3. Preserved in the J.B. Priestley Archive at the University of Bradford – see the catalogue at https://www.bradford.ac.uk/library/special-collections/collections/collections/j-b-priestley-archive/ .

Note 4. Radio Times, London edition, dated 8 July 1971, p.12. For further discussion of this interview see: Walter Greenwood: ‘Old Habits Die Hard’ Interview (George Rosie, the Radio Times, 1971)