On the 3rd October 1936, the Illustrated London News carried a positive notice about a new drama anthology, which it said:

provides an admirable means of making a preliminary exploration of contemporary drama and finding where one’s tastes lie, and at the same time allows of an idea being formed of the trends of thought and of the ‘movements’ which play such an important part in shaping the progress of the modern English theatre (p.52).

The notice particularly picked out four of the thirty plays extracted in the Anthology: Fanny’s First Play, (George Bernard Shaw, 1911) The Sentimentalists (George Meredith, 1910), Richard of Bordeaux (Gordon Daviot, 1932) – and Love on the Dole (Ronald Gow and Walter Greenwood, 1934, of course). It is good to see Love on the Dole selected so early in its stage-life as one of the representative plays of the period (the anthology covers just 1910 to 1934), suggesting how much impact the play had in its first two years on stage and in print. We can also get a snapshot of at least one drama critic’s view of how the play fitted into the theatre of this time, and of how Greenwood and Gow’s work was introduced to a readership who are envisaged in this volume as keenly self-educating and self-taught. The editor of the anthology was S.R. Littlewood, who had been a theatre reviewer and critic for the News Chronicle since at least 1914. (1)

Littlewood is very clear about the function of his anthology and his rationale for choosing scenes from plays:

I have chosen these examples … not always as in themselves the best bits of the best plays. One essential has been that they should prove lively and understandable on their own account. Another has been that the isolated scenes should at the same time induce readers to make further acquaintance with the plays as a whole – above all, by seeing them acted, wherever possible, and taking part in dramatic readings … Every play here represented has been produced as well as published, and is included through my personal remembrance of its performance. (2)

The play scenes are representative rather than necessarily excellent, must stand alone, must have been staged, should lead readers to read further, and – indicated as a priority – should lead readers to see actual performances or to take an active part in readings. The emphasis on active engagement with the works in the anthology is noticeable – it is a starting point for further activity, including in this case not only private reading, but also the (likely amateur) sociable and cultural practice of drama readings, as well as going to the theatre, if possible (Littlewood may be thinking of cost as a possible obstacle here). The stress on active self-education matches the overall aim of the series, as stated on the inner front dust-wrapper flap:

In order … that the careful and discriminating reader may be able to judge for himself [sic], THE MODERN ANTHOLOGIES have been prepared and issued at a popular price and in handy size … These books do … present some of the best that has been thought, experienced and set down in the English language during the past quarter of a century.

Each prose anthology includes samples of the work of twenty to thirty writers. Consequently, seven or eight volumes of the series afford introductions to some two hundred or more modern books, each of which is worth buying and keeping. The value of the series, as a kind of INDEX INCLUSUS, to those who are gradually acquiring a library will be at once apparent. Not only does the choice of books for sampling guide or warn such a reader, but the Introductions give him further help and inspiration.

The series is aimed at those who are imagined to have relatively modest means and so is at a ‘popular’ price (this anthology is marked on the front dust-wrapper flap at 3/6), though not such modest means that they cannot afford to buy enough books to begin to build a library. The ideal reader is imagined as wanting to benefit from some expert guidance, but also as capable of exercising their own judgement. They will apparently not be put off by a little Latin (I had myself not met index inclusus before), and apparently will not be too shocked by meeting some material about which they may have reservations and may not wish to seek out further in future (I take it that is the force of ‘warn’). The anthology draws on a reference to a very well-known phrase in Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy (1869) to summarise its overall educational aim: to communicate ‘the best that has been thought and said’. (3) The inclusiveness and ambition of the series can be judged from the full range of titles, each edited by an expert in their field:

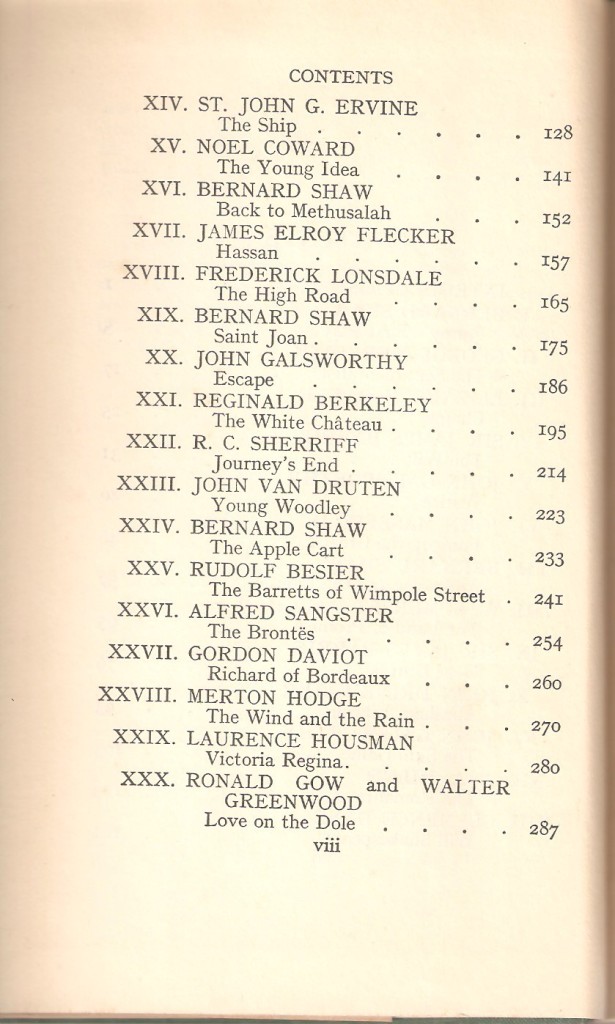

Included in the drama anthology are a number of writers not now very well remembered, such are the vagaries of the canon, the variability of taste and the operations of cultural memory. However, there is one play-wright who is clearly considered a key figure in the period, and who is therefore represented by five plays in this selection of thirty: George Bernard Shaw. Here is the contents list:

I have heard of most of these authors, but have read and seen relatively few of these plays. I actually have read most of the Shaw plays, and seen some. Shaw apart, I think the two plays which have endured best in the theatrical repertoire (and academic canon) are probably R.C Sherriff’s trench play, Journey’s End (1928) and Love on the Dole itself. Greenwood and Gow’s play is the most recent included in the volume, and is printed last (the plays are more-or-less, but not quite, in date order). S.R. Littlewood regards Love on the Dole as representing the most recent development in British theatre, and gives the reader two specific pieces of commentary about it, one as the concluding paragraph of the volume Introduction (p.4), the other as the brief contextualising introduction for the scene from Love on the Dole on page 287 (he writes one for each play).

Littlewood ends his general introduction with Love on the Dole partly because it is the most recent play and the last in the volume, but also as a way of summing up his view of recent theatre. He does not think that this play signifies that British drama has nothing more to say about the middle classes, but he does see a future growth in drama by ‘manual workers’ (I think, sadly, he over-estimated this trend). (4) His sense of the probable audience for Love on the Dole (and any plays like it) as being itself made up of ‘manual workers’ runs counter to a more modern perception that in the thirties its audience was largely middle-class (experiencing working-class poverty in a form they could cope with), which was the main view of the key article by Stephen Constantine from 1982 (5). Littlewood imagines a new drama by working-class writers, but which serves the same functions of entertainment and perhaps social commentary and challenge as that of ‘bourgeois’ theatre, but for working-class audiences. As it happens, he may have hit something up to a point, for the earliest performances of the play in a ‘provincial’ tour after its Manchester premiere did have working-class audiences in venues deliberately chosen by Gow and Greenwood to reach these audiences, including in ‘Salford, Sheffield, Birmingham, Wigan and all the other Northern cotton and pottery towns’ (Gow in the New York Times, 23/2/1935, p. XI). (6) Then, on tour between 1935 and 1937 the play did often pack out variety theatres which generally had popular shows and acts and largely working-class audiences. These included venues such as the Finsbury Park Empire, the Hackney Empire, the Liverpool Empire, the Manchester Hippodrome and, indeed, the Salford Hippodrome (7). Littlewood ends with the humanist disclaimer of historical change that drama, like ‘human nature’ does not fundamentally alter.

This second commentary gives the facts of the first production, and then what makes the play distinctive – its authentic portrayal of its working-class environment and the perspective on this, not from the employer’s viewpoint, but from the level of the working-class home itself. Finally, the nicely-written and concise comment zooms in on the scene extracted and takes the opportunity to refer to the play’s working-class hero, Larry Meath, who does not himself appear in the scene, which features only female characters (who are, indeed, key to the whole play).

I think the scene does meet Littlewood’s criterion of being satisfying in its own right. It is an extract from the end of Act 1, set in the Hardcastle house, and uses the text from the Jonathan Cape edition (pp.41-9). Mrs Hardcastle invites in her neighbours, Mrs Jike, Mrs Bull, and Mrs Dorbell, for a cup of tea, and as it turns out for a séance and then some fortune telling. Topics of conversation include gossip about Sally going out with Larry Meath, and how things have gone downhill since carriage-folk moved out of Hanky Park (in the good old days you could pawn their charitable gifts of shoes and clothes). Then it is time for Mrs Jike to summon the ‘spirets’ (she does this with a hymn on her concertina, something not done in either the novel or the film). The spirits do indeed oblige through her musical intercession. Their superior knowledge is sought by Mrs Dorbell about the outcome of the Irish Sweepstake, and then Mrs Bull reassures Jack Tuttle that she only took the half-crown from his pocket when she laid him out because she knew he’d not need it anymore. However, at that point Sally interrupts: ‘Oh stop it! I never heard anything so daft in my life!’ (p.290). As Mrs Jike complains, this immediately drives the spirits away. Mrs Hardcastle for a while restores peace by asking Mrs Jike to tell Sally’s fortune in the tea-leaves. Mrs Jike sees two men in Sally’s future – a thin man and a fat man (no doubt inspired by her knowledge of Larry Meath and of the desires of Sam Grundy the bookie). Mrs Jike sees growing darkness in the tea-leaves, a darkness which then grows red, ‘like blood’ (p.292). Sally, not surprisingly, is upset (the fortune-telling is based in gossip, but is also a petty revenge for Sally’s assertion of superiority in interrupting the séance) and says the three neighbours must leave: ‘Get outside, all t’lot o’ you’ (p.293). Mrs Hardcastle tells Sally she has shamed her, but Sally responds that they should have nothing to do with such women and their tricks, before ending the scene (and in fact the Act) with a long speech which has no equivalent in the novel:

Mrs Hardcastle. Sally! Y’re not getting’ notions, a’y’?

Sally. Yes, Ah am getting’ notions. It’s about time some of us in Hanky Park started getting’ notions. Y’ call ‘um y’r friends, that pack o’dirty owld women? Oh, Ah’m not blaming ‘um – that’s what Hanky Park’s done for ‘um. It’s what it does to all the women. It’s what it’ll do for you, ma … yes, it will! … and me, too! We’ll all go t’ same road – poverty an’ pawnshops an’ dirt an’ drink! Well, ah’m not going that road, and neither are you, if Ah can help it. Ah’m goin’ t’ fight it – me an’ Larry’s goin’ t’ fight it – an Ah’m starting now. (p.294).

The speech indicates Sally’s emergence as a fighter against the conditions of Hanky Park, which, as she argues reproduce themselves because generation after generation of women are in the same trap which forces them to reproduce poverty because they never have enough money to do anything else. The three older women are denounced by Sally, but she also realises that they are what they are because that is all Hanky Park allows them to be. A cup of tea, a drop of gin, a bet, and the free entertainment of gossip – of which séance and fortune-telling are only specialised forms – is all that they can access. Since these older women have pensions and/or have no children still at home, they are a relative elite in Hanky Park, with some surplus time and sometimes some surplus small change – but it is a very lowly elite and one which does not have the means or inclination for altruism (with the partial exception of Mrs Bull). Sally – partly because she has met Larry’s ideas about the possibility of a different kind of life – is determined to break free, and this speech shows her taking her first steps into agency and away from accepting Hanky Park as normality, as what is to be expected. Once Larry has died after the march against the Means Test, it is a fight she can feels she can only pursue through unorthodox means, and indeed it might be said that her ‘escape’ to live as Sam Grundy’s mistress (for a time) in order to get her father and brother jobs is really a defeat, an admission that she too can find no real way out of the conditions of Hanky Park.

The scene has a satisfying dramatic shape as it draws the reader into the world of Hanky Park, into the living out of that environment by women, into what seems at first merely a harmless way of passing the time, but which develops into something tenser and, for Sally, more intrusive. Mrs Jike’s prediction, based on her knowledge, is in its way accurate: Larry will end in blood and darkness and Sam Grundy’s money will prevail. Sally’s big speech is a sign of hope for the extract to end on, though for anyone knowing the whole play, only a temporary one. The scene is representative of the whole play too in providing entertainment and a serious social point: the older women’s dialogue, self-interest and trickery can be enjoyed as comic, while Sally’s intervention puts their business and self-interested perspectives into a different and larger context for the reader, and the extract ends on that serious note.

As an introduction to Love on the Dole and its place in recent drama, the scene and its brief introduction seems to me to work well. If, in 1936, you wanted to know about this famous, somewhat controversial and much commented on play, then the Nelson Anthology of Modern Drama would help you. Clearly Greenwood, Gow and Cape gave their permission for the scene to be included (and were no doubt pleased about this potential boost to sales of both theatre tickets and play copies). I think that Gow, as a former school-teacher, and Greenwood, coming from an autodidact family tradition would, beyond commercial considerations, have approved of the volume’s intentions. Greenwood’s mother Elizabeth had inherited and was proud of a book-case of books from her father, a union activist and keen socialist (see Walter Greenwood: a Biography). She was determined to educate Walter in the things which mattered and only allowed him out to play in the streets of Hanky Park when he had correctly recited from memory a poem of her choice (one was Wordsworth’s ‘I wandered Lonely as a Cloud’, first published 1807). She also later bought him books, almost certainly second-hand, including Everyman editions of Shakespeare (There Was a Time, pp.80-1 and 201 – see Walter Greenwood’s Memoir: There Was a Time (1967).). When, in the twenties, Walter was working as a teenage stable-lad, he came home complaining that he had been told to exercise a horse called Sisyphus: ’what a daft name for a horse … it doesn’t mean anything’. His mother responds swiftly to correct his educational deficit:

I knew that I had put my foot in it the instant I received the shut-eye look of disdain which was reserved for exhibitions of ignorance or bad manners.

Without a word Mother rose and crossed to Grandfather’s glass-fronted book-case and took out A Smaller Classical Dictionary whose fly leaf was marked ‘6d’, as were several of the books which she was in the habit of bringing home. Of late my sister and I had been hearing a lot about one of my mother’s regular customers at the café, a professor at Manchester University. It was on his advice that she selected many of the titles from the threepenny and sixpenny shelves at the second-hand booksellers. She opened the book at the proper page, placed it on the table in front of me, sat down and said ‘Proceed … and read aloud’ … She pointed at the bookcase … ‘You don’t need money to be well-off … get the habit of reading and you will have a companion for life (There Was A Time, pp.139-140) (8).

I think Elizabeth Greenwood would have approved of the Nelson Anthology of Modern Drama and her son’s presence in it. Perhaps the only problem would have been the price – three shillings beyond the Greenwood family’s modest means for book buying.

NOTES

Note 1. When he described Sadler’s Wells as a ‘poor, wounded old playhouse’, according to the Sadler’s Wells history web-site: https://www.sadlerswells.com/about-us/history/.Though always known professionally as S.R. Littlewood, he was Samuel Robinson Littlewood (1875 – 1963) and his Times obituary records that he had been a drama critic for fifty years (12/8/1963).

Note 2. An Anthology of Modern Drama, edited by S.R. Littlewood, Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, London, 1936, p.1. Subsequent page numbers are from this edition and will be cited in brackets in the text.

Note 3. The series may also share Arnold’s belief that culture and education were necessary defences against the ‘philistinism’ of industrial society and narrow self-interest. See his Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_Arnold .

Note 4. The Dr Pellizzi referred is likely to be Camillo Pellizzi (1896-1979) who taught Italian literature at University College London in the twenties and thirties. The particular work on drama to which Littlewood alludes might be Pellizzi’s Il Teatro Inglese of 1934 (Fratelli Treves, Milan). Information about Pellizzi is derived from an article about his correspondence with Ezra Pound (The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 70, no. 2, 2009, pp. 302–305, by Camillo Pellizzi, and Luca Gallesi: “How I Lost Ezra Pound’s Letters.”: open access via JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.25290/prinunivlibrchro.70.2.0302.)

Note 5. ‘Love on the Dole and its Reception in the 1930s’, Literature and History, Vol 8, Autumn 1982, pp. 232-47. Available only in hard copy in university libraries.

Note 6. For further detail see Chris Hopkins, Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole, Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, 2018, p.5.

Note 7. For further detail see Chris Hopkins, Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole, Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, 2018, pp. 4-5.

Note 8. The Smaller Classical Dictionary referred to is probably a concise edition of the larger classical dictionary by Sir William Smith (1813-1893), a work dating back to 1872, and which was reprinted a number of times in Everyman editions, including in 1916. Smith made important contributions to school education by writing classical and biblical dictionaries. See his Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Smith_(lexicographer)