Introduction

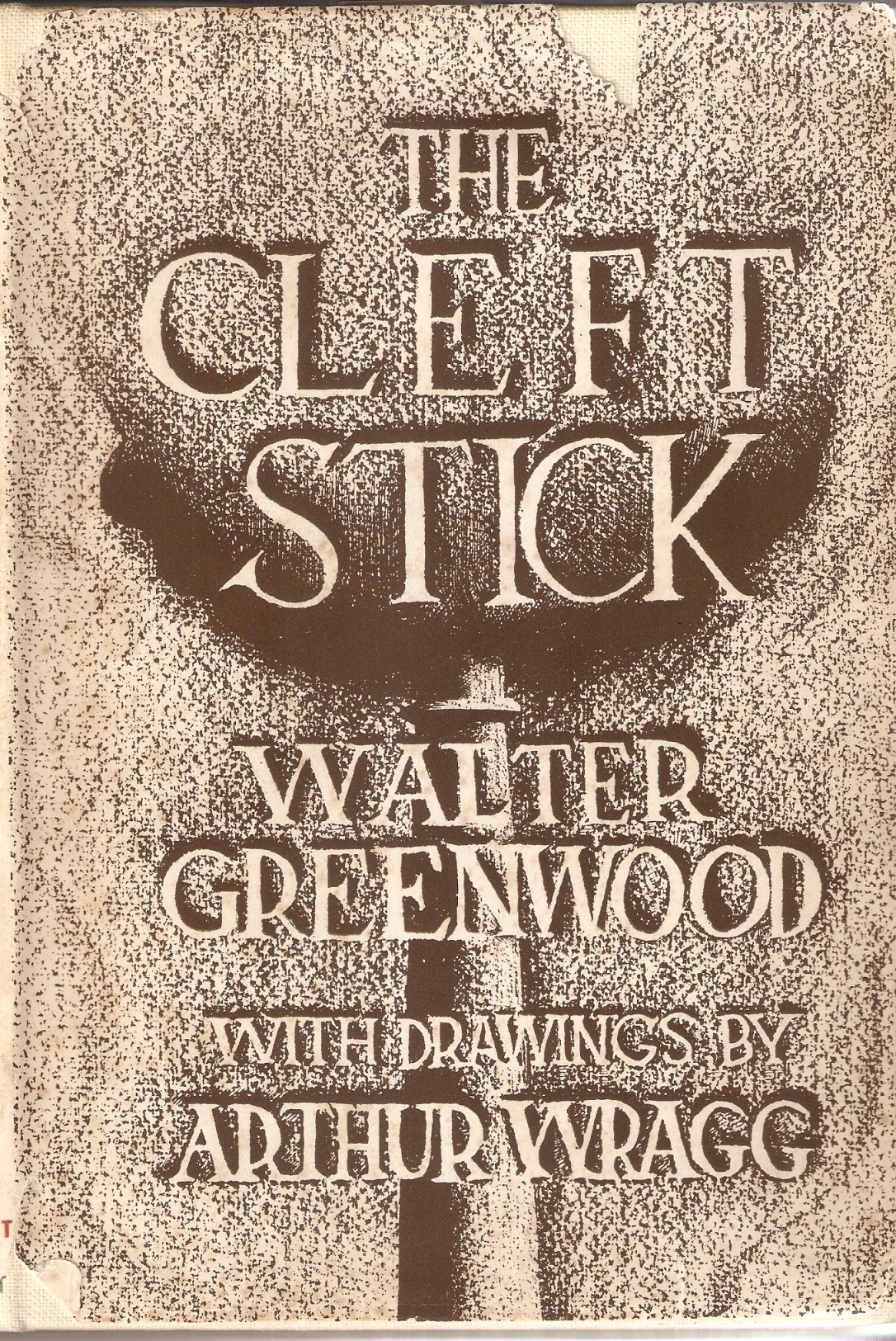

Walter Greenwood is well-remembered for his novel, Love on the Dole (1933), which sold some 46,000 copies and was seen on stage by around 3 million people in Britain. Love on the Dole was seen as authentic testimony from a working-class author who had experienced unemployment – a desperate experience which nevertheless gave him the opportunity to write a major work about the lives of working-people in Salford. He did not though begin by writing a novel, but by writing short stories about working-class life intended for fiction magazines. However, only one of these stories was published. It was not until 1937 that Greenwood published his earlier short stories in a book called The Cleft Stick, co-produced with the Sheffield-trained artist Arthur Wragg, who drew a monochrome illustration for each story, as well as illustrated end-papers and the dust-wrapper. Both Greenwood and Wragg had a certain celebrity status as working-class artists and the book was widely read. The Cleft Stick has never been reprinted, but it was widely written about then as a controversial (and even bleaker) sequel to Love on the Dole. There was not so much working-class work published in the nineteen-thirties that we can afford to forget a once famous collaboration between a successful working-class writer and a successful working-class artist. I am currently working on getting The Cleft Stick republished, but in the meantime below the dust-wrapper image are synopses of each of its stories, with some brief indications of links to characters and themes in Love on the Dole.

The Cleft Stick: Contents and Story Synopses

Author’s Preface

Explains how Greenwood wrote the original stories while on the dole, why magazine editors rejected them (with one exception) and how he came to revisit them with Arthur Wragg’s help in 1936.

- A Maker of Books – a story about a factory worker who thinks he will escape his current life by setting up as an (illegal) street bookie. Alas, his experiences are negative and he loses all he and his family have, but we see him still convinced at the end of the story that betting will rescue him one day if only he keeps investing.

- Patriotism – a new story Greenwood wrote for this volume in 1936, but set earlier than all the other stories and focussing on how a group of Salford characters persecute shop-keepers with German or ‘foreign’ names during World War One, and fully enjoy the stolen fruits seized from broken shop-windows during the exercise of their vigorous ‘patriotism’. See the article about a related but unpublished story: https://waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com/walter-greenwoods-christmas-present-for-arthur-wragg-1937/

- Mrs Scodger’s Husband – Mr Scodger is a blacksmith, but also a diminutive man who is dominated by his wife, whose main pleasure in life is playing the trombone at the ‘North Street Mission Hall – when she is not practising at home. In a rare moment of luck, Alf Scodger wins a bet on a horse and on this basis tries to renegotiate his house-hold relations. He is uncertain that the harmonium on which most of his winnings are spent by Mrs Scodger is an improvement, but he has at least drunk some of the money before handing it over.

- The Cleft Stick – Mrs Cranford has an unemployed and useless husband, and many more children than she can feed, however much laundry she takes in. She feels she can bear no more and decides to kill herself with the help of the gas-oven– but she has no penny to put in the meter. Instead she pawns some of the laundry and buys a nip of whisky That is her ‘cleft stick’ from which there is no escape. This metaphor, from Greenwood’s use of it as the title of the whole collection, presumably sums up most of the working-class lives in Hanky Park. However, there is a glimpse of hope at the story’s end: a female neighbour explains that Mrs Cranford is feeling so bad because of the ‘change of life’ – something of which she has never heard – and that the good news is that now she at least will not have any more children. It seems quite remarkable to find a male author in the thirties dealing with the menopause in his fiction, but in fact The Cleft Stick has a marked interest in women’s lives, as in the following story – and perhaps more so overall than Love on the Dole.

- Magnificat – Amy Wilkinson is a mill-girl who enjoys going to the palais de dance, and especially because the professional male dance-partner who works there reminds her of the male Hollywood stars she also enjoys every week. Alas, one assignation with this flesh-and-blood heart-throb leads to pregnancy, something she has not learned about from the movies. Though her parents tell her she is a slut and ruined, and can never marry, and though she contemplates suicide, she in the end reads her Bible and decides that just as the Virgin Mary’s story turns out all right so will hers: indeed she reflects that baby will be the only thing she has ever had which is wholly hers (the dancing-partner has fled Salford). This is a story deeply unlike anything in Love on the Dole, where religion plays very little part. Is this the influence of Wragg whose work was much concerned with how the modern world interpreted Christianity, or was there originally a religious strand which did not make it into the novel? The story has an ending unusually ambiguous for Greenwood – it may be that Amy is deluded and will soon learn what it is really like to be a single mother in nineteen-thirties Salford, or it may be that she has found an unlikely support in her highly individual interpretation of the New Testament.

- The Little Gold Mine – Mr Hulkington is a kind of character who does not make it into Love on the Dole: he owns a successful grocer’s shop in Hanky Park and is well enough off. The Glynne family are not so well-placed and constantly need fresh credit on the slate, but Mrs Glynne finds that the elderly Mr Hulkington is readier to give her pretty daughter Nance credit than herself. Soon Mrs Glynne encourages Nance to entrap Mr Hulkington into marriage, though she already has a young man called Harry Blake. As so often Greenwood is happy to deal with controversial material, and Nance, while rather explicitly refusing to sleep with Mr Hulkington, becomes completely dominant and increases her power by continually dosing her husband with increasingly large amounts of his own stores of whisky, day and night. He soon succumbs and dies, and she is able to marry Harry Blake, who as it turns out loves the profits from the ‘Little Gold Mine’ much more than he ever loved Nance. Working-class people in Hanky Park certainly relied absolutely on such small shops for all their daily needs, but the shop-owners are markedly missing from Love on the Dole, which is exclusively devoted to the poorest people. This story again introduces an aspect of Salford life which is missing from the novel – but only to use it to show how all wealth corrupts.

- Joe Goes Home – Blind Joe Riley is a character who appears at the very beginning and very end of Love on the Dole. He is the ‘knocker up’ who wakes at dawn for work all those who cannot afford an alarm clock (that is everyone in Hanky Park) by tapping sharply on their bedroom windows with a long pole with wires attached at the end. That is all we know of him in the novel. Here is added a very little – just the sad end of the story of this man who lives alone and has to work into old age. Joe becomes too ill to work and must go into the work-house. He regards this as a death-sentence and gives away his few possessions (including his knocking–up pole). Neighbours assure him he will be back home soon enough, but once the ambulance has collected him, they too talk of him as if he were surely dead already: ‘seventy-five’s not a bad age’.

- ‘All’s Well that Ends Well’ – This story again features a character and a milieu which is quite alien to the novel Love on the Dole. Mrs Babson is a widow who owns a very successful business, consisting of five ‘High Class Supper Bars (Fish, Chips, Beans and Peas – Ribs Friday) located in the busiest streets in Salford. The story concerns Mrs Babson’s vigorous attempts to make sure her daughter marries someone worthy to take over the business in due course, and her own ironic deception by a seemingly superior car salesman who is not all he seems (being already married). As in ‘A Little Gold Mine’, the story explores the psychology, drives and vulnerabilities of those in Salford who are not on the breadline, but successful entrepreneurs.

- A Son of Mars – The protagonist of this story is familiar from Love on the Dole – he is the hyper-masculine and aggressive ex-Sergeant-Major, Ned Narkey. Here, though, we get even more insights into his abusive attitudes to women and his selfishness. The story opens with the unemployed Narkey and his wife waiting for a hearse to collect the coffin of one of their recently deceased children (they have ten, of whom seven now survive, each ailing). Nark’s wife has a black eye, is emaciated and is pregnant again. Narkey does not attend the funeral but waits at home for the life-insurance men to hand over the three pounds generated by the child’s death – he wants to buy some cigarettes and go to the pub. Soon he is able to go out drinking and to meet a mistress – but he also runs into another woman who is pregnant by him. He uses threats of violence to quash her demands that he pays towards the keep of the baby. He ends the day back in the pub, drunkenly arguing with other customers that his life while unemployed is a misery to him and that the working man’s only hope is that another war will break out soon.

- ‘What the Eye Doesn’t See’ -This is a unique Greenwood Hanky Park story – it has a happy ending! A couple who have only been married for eleven months have their first major row, after a spoon is dropped on the floor after dinner. Neither will pick it up nor speak to each other till the other gives an apology and admits it was their fault. However, this trivial incident is really standing in for a major disagreement about whether they should go on holiday this year or move to a house in a new housing estate. The issue is resolve with the help of a neighbour and her small boy – the boy picks up the spoon and accidentally drops it down a drain, while the neighbour explains that the rent at the New Estate is completely unaffordable. Harry and Lil both save face and are delighted to be happily reunited and on their way to the Isle of Man for their two week annual holiday.

- A Quiet Life – Stephen Wain is a clerk at the Law Stationers shop, Blore and Smith. He has worked there for forty-eight years, since 1882 using his perfect copper=plate and his skills as an illuminator to produce handwritten legal documents on parchment and sometimes decorative headings or facsimiles of ancient manuscripts. In fact, he is what makes Blore and Smith’s a successful business, though he is paid only sixteen shillings a week. However, Stephen Wain is happy – he loves his work, he is content on his lodgings and he likes most to be alone. Eventually the genial if not generous Blore senior (Smith was a fiction) dies and his much less interested son takes over. Worse, typewriters are now used for legal documents and illumination is out of fashion. Soon Stephen is told only to come to work if there is a special commission and to live on his ten shillings a week old-age pension. He misses his work and he has to spend his days in the park, because his landlady does not like him staying in the house during the day-time. Inevitably he catches pneumonia and dies. As a number of Greenwood’s writings suggest he feared himself that he might end up as a clerk, ‘cursed by good handwriting’, but this story shows a deep empathy with this clerk as a craftsman whose work is exploited for profit but never appreciated.

- Don Juan – Danny Evans is a car mechanic who exhibits a number of what we might now call obsessive behaviours, which the story blames squarely on his egotism: ‘his low stature was more than compensated in his high opinion of himself’ (p. 171). The behaviours which make him both odd and anti-social in the story are not at first sight evidently linked, but as the story develops, it suggests common roots in a self-obsession. Danny is a dandy, always turned out immaculately with a good suit, wing-collared shirt, chamois gloves and a silver-topped walking stick, the whole oddly always finished off with a cap rather than a bowler or trilby. He also likes to pretend that he is a traffic police-man, often stepping into the middle of the road to direct traffic, if there is no authentic officer on duty. If he sees an engine or machine of any kind he is likely to take it apart on the spot, whether he owns it or not. But above all, as the story title suggests, he is obsessed with women in a disturbingly strange way: ‘his hobby was women. A woman soon disenchanted him, but women——!’ (p. 171). The story centres on his exploitation of women in temporary relationships, but also on how this leads to his downfall. Danny is considering with a pathological anxiety a more permanent relationship with the daughter of the owner of a successful garage business, when his past returns to haunt him. The brother of a woman called Mary Barson who he has taken to Blackpool for the weekend turns out to be the famous boxer, Battling Barson. Danny is compelled to take responsibility for her pregnancy and very unwillingly to enter into a permanent relationship. This resembles a number of stories in The Cleft Stick about exploitative men and unplanned pregnancies, but its portrait of Danny’s obsessions makes it one of the strangest.

- ‘Any Bread, Cake or Pie?’ – Harry and his school-friends are always hungry, for the very natural reason that they are growing boys and that their families don’t have enough food. This story brilliantly depicts how the quest for more food on one particular but characteristic day makes all other thoughts impossible. Harry is big and dominates his friends, but essentially they are all so hungry it is every boy for himself. They have a number of ways to get food when they are desperate, including diverting Mr Hulkington the grocer’s attention, while they steal from his counter, but this pays increasingly fewer dividends as he is alert to their tricks. They also try begging scraps from Babsons high-class supper bar, but are rebuffed as pests. Finally, when Harry has delivered his newspapers (and missed what passes for tea at home), the boys go to wait outside Marlowe’s works for the end of day whistle and call out what is a traditional cry: ‘Any Bread, Cake or Pie?, hoping for some left-overs from the workers’ packed lunches. Only one gift is forthcoming – a package of beef-dripping sandwiches. The boy who has been given the package starts to share it out, but Harry steals the whole package and runs off to eat them all. However, he is still hungry and is tempted to the point of stealing a purse from a woman’s pocket. Sadly, it contains only pawn tickets and three half-pence. Harry thinks that if he returns the purse to the woman’s home, he is bound to get a reward greater than three half-pence. The woman’s husband thanks him grumpily and closes the door. The tough Harry weeps, still very, very hungry. See for a more detailed analysis of this story and its illustration: ‘Any Bread, Cake or Pie?’: Walter Greenwood’s Hunger Story (1937)

- The Practised Hand – Mrs Dorbel’s long-term lodger, Ben, has been ill for fourteen weeks and though on the point of death, she thinks, he is ‘lingering’. This worries her for she has been paying two pence a week into a life insurance policy on him for twelve years and when he dies will receive twelve pounds and ten shillings. Going to the pub for a small whisky for her cough, she meets her neighbour Mrs Nattle and laments the sad state of her lodger. Mrs Nattle has some relevant experience, for her husband had lingered a little and had to be helped by Mrs Haddock, a ‘handy woman’ who acts as a mid-wife at the beginning of life in Hanky Park and as a layer-out at the end. Mrs Haddock when called upon says she will see if she can help the lodger, for a fee of ten shillings. As it turns out, Mrs Haddock is able to help and within half an hour the lodger is dead and Mrs Dorbel and Mrs Nattle setting off to collect the life insurance money (and to ask the parish to bury Ben, since he is penniless). They lament that such a good lodger is gone, but feel a drink will do them good. The Manchester Guardian reviewer of The Cleft Stick felt that this was the most shocking story in a volume that he regarded as generally bleak – he was especially appalled at the idea that Greenwood had also written a one-act play version of the story and hoped that no one would go to see such an inhuman play. See for a more detailed analysis of the story: Walter Greenwood’s Two Manchester Hospital Stories (1935 and 1945)

- The Old School – the final story in the collection is in fact not a story but, as its sub-title states, ‘an autobiographical fragment’. Greenwood had originally written this for Graham Greene’s 1934 collection of essays recalling authors’ generally appalling school days, the whole collection amounting to a severe critique of the British education system. Most essays were by public school boys, with Greenwood’s being the only one about an elementary school of the kind which most working-class children attended. Greene had been impressed by Love on the Dole the previous year and probably asked Greenwood to contribute, partly to help this working-class author, as well as to slightly broaden the scope of his project. The piece is about Greenwood’s time at ‘Langy Road’, that is the Langworthy Road Elementary school, which he attended from the age of five until he was allowed to leave early at the age of thirteen in order to earn money for his family after the early death of his father. In fact, much of Greenwood’s essay is about his poor family circumstances, which explain why his school attendance was brief. He also makes clear that school was a fruitless experience as far as he was concerned: ‘to me the Old School was a place to be avoided, a sort of punishment for being young’ (p.215).

See also my more detailed discussion of some of the stories and their accompanying images in my open access article in the academic journal, Word & Image: