In the papers of the artist Arthur Wragg held in the V&A archives is a folder titled: ‘AAD/2002/11; Correspondence c.1935-1941; Friends’. (1) There are letters mainly from twelve of Wragg’s friends, organised under their names (together with a few other more miscellaneous letters). Fairly regular correspondents include Sir Stafford Cripps and family members, Reverend Patrick McCormick, Ethel Mannin and Walter Greenwood. Among other previously un-noted letters from Greenwood to Wragg is a short story which was, I think, never published and was sent to Wragg as, indeed, ‘A Christmas Present’, which is the title at its head. The story is handwritten by Greenwood and covers six pages of note-paper (unpaginated). It is dated 8th December, 1937.

The story is set in Hanky Park, the scene of Love on the Dole, as well as of The Cleft Stick (1937), a textual/visual collaboration between Greenwood and Wragg. (2) ‘A Christmas Present’ has as Its central character ‘old Mrs Harrop [who] lived in the end-house of one of Hanky Park’s many dilapidated streets’ and the story which is told from her point of view is set during the First World War. We do not learn much of her backstory and Mr Harrop does not seem to be extant, but in recent years she has been looking after her orphaned grandson, Joe. Now he has volunteered for the Lancashire Fusiliers and been sent to the trenches. Joe is important to her for both economic and emotional reasons. She has very little income, and with Joe gone she cannot manage. At this particular point, she does not think she can get to the end of the week: she has nothing left to pawn, and has exhausted her credit with Mr Hulkington, the grocer (who is mentioned in Love on the Dole and is at the centre of a whole story in The Cleft Stick). (3) She thinks to herself that all women in Hanky Park are ‘imprisoned … forever within the narrow confines of that triangle’: home, grocer’s, pawnshop. She can only lament that Joe, who was doing well in his job as an engineer, has gone and that the war is so costly: ‘he oughtn’t to have gone’.

Walking through the streets, she passes Keppel’s pork butchers (also referred to in the story ‘Patriotism’ in The Cleft Stick, discussed below) and realises that Christmas must be approaching – the only reason why Keppel would have a whole pig hanging in his shop-window in Hanky Park. She had forgotten about Christmas, but decides she would like to send a letter and a present out to Joe in Flanders. However, she will have trouble generating any surplus when she cannot even afford necessities. She makes efforts beyond the ordinary for this special need. First, she offers to clean the local pub, but the landlord says no, fearing that she is so frail she may die on his premises (no room in the inn, perhaps?). Then she approaches Mrs Nattle (another character from Love on the Dole) to ask to borrow five shillings in the form of a clothing club cheque, but Mrs Nattle has no doubt this is too bad a risk to take on. (4) Finally, Mrs Harrop realises there are things she can give up – if she eats no meat next week and gives up milk in her tea, she can raise seven-pence and afford a pair of socks for Joe and a stamp for a letter. Mrs Harrop cannot read or write, but her neighbour Mrs Middleton acts as ‘scribe and interpreter’ to produce a letter to Joe. Just as Mrs Harrop is setting out to buy the socks, a telegram arrives: Joe has been killed. Mrs Harrop simply says to herself in the final line of the story: ‘He was always such a good lad to me’.

This is a sad tale indeed, with no offer of escape or amelioration for Mrs Harrop: her only source of survival and comfort is gone, and Joe’s life is cut short. Nor does the story offer much hope for European civilisation – the run up to Christmas has no impact on the killing-fields of the Western front. The title evidently has several meanings. The story is about Christmas as it is now (or anyway some twenty years’ earlier), it is in itself a present for Arthur Wragg, it is about a Christmas present, and of course it makes an obvious reference to Dickens’ still then very popular A Christmas Carol (1843), with its three ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present and Christmas Future. (5) The comparison with the Dickens story is bleak – where it offered the possibility of change, and particularly the possibility that the rich might do something to improve the lives of the very poor, there is no one to care for Mrs Harrop apart from the working-class orphan who feels he must serve his country. Once Joe is gone, and she has exhausted the only mechanisms for survival (which have to be paid for in due course anyway), there are no further safety nets. Part of the point of Greenwood’s reference to the Dickens story may be to point out that in Hanky Park conditions of nineteenth-century poverty have not much changed in the last century, and that A Christmas Carol’s call for philanthropy has not yet been heard in many parts of thirties Britain. Greenwood’s story notably refuses any sentiment (other than Mrs Harrop’s affection for Joe) or explicit commentary – Mr Hulkington, the pawnshop proprietor, the pub landlord and Mrs Nattle are not portrayed as modern-day Scrooges, as they might easily have been, but are instead seen as ‘only’ applying sound business-principles. Mrs Harrop would not be a safe investment: what other values are there?

There are a few glimmers of light though. The one person, Mrs Middleton, a working-class neighbour, who does help Mrs Harrop by writing her letter, does it for free. In this she makes true an idea which in Love on the Dole is stated but, on the whole, rendered ironic. There Mrs Dorbell (in fact, far from a helper of others) declares ‘It’s poor as ‘elps poor aaaall world over’ (6). Moreover, Mrs Harrop herself is a moving example of a character whose liking for another person may start in her need for his economic contribution, but seems to develop into something beyond this, though she cannot well articulate it. Joe is of course her grandson, and though this kinship is so bound up with her material needs, she can in her own way look beyond her own need to survive. She makes sacrifices to afford her Christmas present, and if these are in a sense rendered futile by Joe’s death, she has shown a spirit of selflessness in what is the largest gesture she can afford.

Greenwood’s writing is, of course, usually strongly linked to the nineteen-thirties and its crisis of poverty and unemployment. Love on the Dole indeed has a very specific time-period. It begins with Harry Hardcastle starting his seven-year apprenticeship with Marlowe’s Works and ends with the consequences of the severe economic measures enacted by the National Government after their election in October 1931, giving the narrative a time-line from 1924 till 1931. Here, though, we have a story set some twenty years back in the War-years. There is some reference to the War in Love on the Dole, both as something characters naturally remember and in a few thoughts about a possible future war. Thus, when Harry begins his seven-year engineering apprenticeship, Larry observes that there is not that much to learn these days and tells Harry that during the war when women were taken on to replace men, they learnt all they needed to know in no time (p. 47). (6) Harry, beginning to worry about how quickly his apprenticeship is passing and that he’ll be time-served as soon as he is nineteen, thinks back to watching nineteen-year olds marching off to war the last time (p. 75). Harry, paid at youth rates, reflects that ‘had the present been war-time, the authorities would have termed him a man and hauled him off to the trenches’ (p.91). We also hear a little about ex-sergeant-major Ned Narkey’s war service, and that of Ted Munter and Sam Grundy (when Sam’s running of Crown and Anchor games established the funds for him to set up as a bookie after the war). (7) However, the First World War and the fear of another war does not seem that central a pre-occupation of the novel – it was written early in the thirties, when unemployment was the more immediate crisis.

That is not to say that Greenwood was not interested in the impact of the First World War on Hanky Park. He left school in 1916, aged thirteen, so had clear memories of how the war was experienced in Salford. His memoir, There was a Time (1967), includes, among other things, the declaration of war, anti-German feeling, men joining up, their poor pay, the sending of field post-cards, the commandeering of horses, the desperation of Greenwood’s teen-age pawnshop work-mate Reggie Sniblo to join up as soon as he is of age, and very soon the inevitable news of deaths from the front (see pp. 77, 104-5, 93, 89, 115-6). Greenwood meets his friend Nobby, who as a wartime telegram-delivery boy, has soon developed an indifference to the news he delivers:

‘And I’ve not got all day to waste muckin’ about waiting for Ma Boarder. Look at this lot … ‘Comin’ in by the dozen they are. Bert Harrington’s killed, y’know … an’ Reggie Sniblo … [and] Dick Dacre and Alfie’s Dad’. (p.115).

Mrs Boarder’s telegram tells her that her husband is dead. Two weeks later, a second telegram tell her of the death of her son and she says only (and perhaps a little like Mrs Harrop?) ‘Nay, nay. Not our Harry as well’ (p.116). Leaving the reader to make their own judgement through the lack of explicit commentary is powerful, and echoes the similar technique of ‘A Christmas Present’, written thirty years earlier.

The Cleft Stick, like Love on the Dole, seems mainly set in the thirties, but it has one story among its fifteen which is set during the First World War. I have always thought this slightly jarring, since in a collection of short stories each of which contributes a snap-shot to a portrait of a contemporary Hanky Park, this one story goes back to a different time-period. That may be partly an effect of my imposing Love on the Dole’s strict time-line on the short-story collection, when it does not in fact have such an explicit temporal framework – however, the majority of the stories do seem to take place in a post-war world. The story, the third in the collection, is titled, simply, ‘Patriotism’. It opens with and indeed focusses on a very poor resident of Hanky Park – one Mrs Harrop. Some details of this quite long story – fourteen printed pages, so perhaps four times as long as ‘A Christmas Present’ – flesh out Mrs Harrop’s back-story. However, she is revealed in a very different light, or perhaps really as a completely different character. The story opens with Mrs Harrop’s reaction to a ‘coloured lithographic’ recruiting poster:

His Lordship pointed a finger at all who glanced up or stopped to look at him. Out of his mouth flowed a wavy white line which encompassed the following utterance … ‘YOUR KING AND COUNTRY NEED YOU!’ (p.28)

(8)

Mrs Harrop cannot read, but hoping the poster may offer free soup, asks Mrs Bull (another character also in Love on the Dole) to oblige with an interpretation. Mrs Bull reads the text out loud and adds her own commentary: ‘Oh they do, do they? Well, I’d like to be able to tell ‘em what I need, by gum I would’. Mrs Harrop realises that the poster offers her nothing for her needs, that it is addressed only to men, and that Joe has already gone to answer this call, to her cost.

We get some more precise details of Mrs Harrop’s economic plight than we do in ‘A Christmas Present’:

Joe was Mrs Harrop’s grandson who had exchanged a tradesman’s pay for a shilling a day, a khaki uniform and a dependant’s allowance payable to his grandmother every Friday at the post office.

‘Joe doesn’t understand,’ Mrs Harrop told herself, these words explaining to her own satisfaction the impossibility of a woman paying her way on the meagre money allowed by the War Office to the dependants of the soldiers of the King. (p.29)

Suddenly a disturbance breaks into her thoughts – a ‘row’, she thinks, between neighbours which will provide some free entertainment. In fact, her neighbours have just seen the newspaper headlines announcing the sinking of the Lusitania by a U-Boat (the story of the sinking broke on 8th May 1915 and riots began a few days later) and are enraged by what they see as without any doubt the German murder of civilians. (9) This sparks off one of Mrs Harrop’s neighbours, Mrs Middleton (the helpful literate neighbour in the Christmas story), to make some more local connections:

She turned to her neighbours … and began to inveigh against spies, Germans and civilian shopkeepers with foreign names who were making fortunes out of English women whose husbands and sons were being killed in the trenches in a foreign land (p.33).

Already, the windows of Keppel’s pork butchers have been broken by an angry crowd, and his shop emptied of every piece of meat and sausage. At this point we enter what might seem to us the askew mind-set of these poor Hanky Park women: ‘Mrs Harrop felt she had been victimised. Occasionally she had patronised Mr Keppel; consequently, who had better right than she to be one of the first in looting?’ (p.33). Mrs Harrop sets off immediately, quickly followed by all her neighbours, to make sure she is there at the beginning at Mr Schwartz’s weekly-payment drapery shop. She indeed takes a lead by throwing the first missile at Schwartz’s, but in the rush and brawling for goods which follows she finds she has only ‘managed to get … a parcel of men’s socks’ (p.38). Eventually, after considerable kicking and clawing of her neighbours, Mrs Harrop bears off two men’s overcoats, a pair of men’s boots and the socks. She and all the other women head straight for the pawn-shop, and then ‘she called on Mrs Sarah Ann Nattle and sold both pawn-tickets for a large “nip” of spirits, a currency Mrs Nattle often used in these transaction’ (p.39). Mrs Harrop spends the rest of the day at the Duke of Gloucester, ‘until closing time when the patrons went home obstreperously drunk, singing patriotic songs’ (p.40). (10)

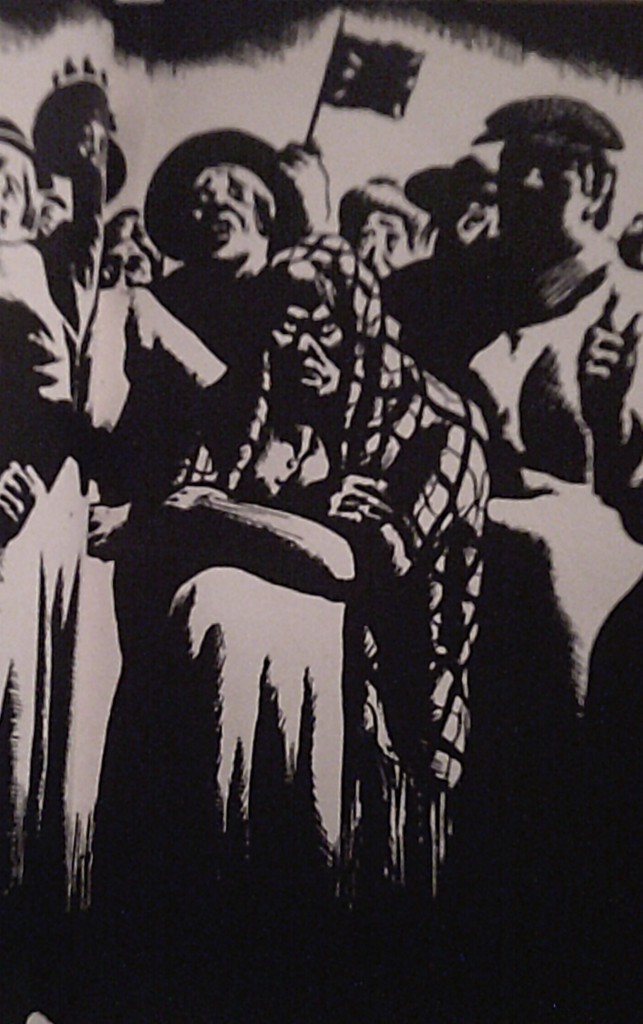

As for each of the stories in The Cleft Stick, there is a Wragg illustration, in this case filling a double page. I think Mrs Harrop, as the focal point of the story, must be the central, foregrounded figure in the drawing. Her shawl perhaps suggests she is the poorest of the crowd of women, in contrast to the rest who each have a hat to wear. As so often in Wragg’s illustrations, masses of an absolute black contrast starkly with the cream of the page, suggesting a lurid but limited lighting from above, and indeed a night-time scene (though the text sees it as a day-time incident). If the shawled woman is Mrs Harrop, she also looks the meanest in mood from her facial expression and folded arms. The story’s title, ‘Patriotism’, is picked up in the background of the drawing by the union flag being waved, though we might read into its position at the rear of the crowd that it is not patriotism in the most obvious sense which is in the forefront of these women’s minds (or is the point that their avarice and quest for vengeance is precisely seen here as the usual root of ‘patriotism’?).

The Cleft Stick was published in mid-November 1937, so ‘A Christmas Present’ was presumably written afterwards, but clearly has a relationship to the short story collection. While Love on the Dole was specifically about the impact of the Depression, The Cleft Stick may instead, with the inclusion of a First World War story and no precise or explicit such time-frame, suggest that poverty is the long-term situation of Hanky Park, slump or not. Another reason why in ‘A Christmas Present’ Greenwood went back to Hanky Park during the First World War may be that, like all good presents, it is carefully designed for its recipient. Arthur Wragg was a prominent Christian socialist pacifist artist, as is seen in his juxtapositions of text and image in his controversial and famous first two books, The Psalms for Modern Life and Jesus Wept – A commentary in black-and-white on ourselves and the world to-day (Selwyn & Blount, London, 1934 and 1935). The images in these two books resemble the illustrations in The Cleft Stick, but are less bound by broadly realist conventions, and draw on surreality and the metaphoric. A number of the drawings suggest that Wragg would have appreciated the way in which ‘A Christmas Present’ saw links between the evils of want and war. For example, there is the image titled ‘Betrayal’ in Jesus Wept, where Wragg, like Greenwood (and Mrs Bull and Mrs Harrop), considers the famous First World War Kitchener recruiting poster, and the question of when and how your country needs you, and whether it meets your needs in return. Had Joe survived, perhaps the dole, at best, would have been his recognition in 1934.

It is good in its own right to recover an unknown and unpublished short story by Greenwood, but it also adds something to our understanding of the relationships across the three major works by Greenwood which centrally portray the poverty of Hanky Park in the period between the nineteen-tens and the nineteen-thirties. These deploy quite different modes at times, the often satirical stance of The Cleft Stick stories contrasting with the often didactic realism of Love on the Dole, and both in turn with the more subtle There Was a Time, which allows the narration to work on the reader more implicitly, dispensing with obvious authorial commentary or interpretation. As I suggest in a recent article in the journal Word & Image, Greenwood had quite a range of alternative ways of representing poverty in Love on the Dole and The Cleft Stick, works which have complex textual relations. (11) ‘A Christmas Present’ adds another piece of new text to that set of relationships, and also shows that, even in the thirties, Greenwood had different techniques at his disposal, and that Hanky Park was an imaginative world which he revisited quite often after nineteen-thirty-three. The habitual focus on him as only the author of Love on the Dole, and on that novel as a self-contained text, has simplified the formal choices, approaches, and range of this working-class author, as well as the complex genesis of his best-remembered work, and his reworkings of it.

NOTES.

Note 1. Read on my visit to the V& A Archives (then at Blythe House, 23 Blythe Rd, London W14 0QX) on 20/6/2019. I am very grateful to the Archives and the Archivist for assisting with my research on Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg.

Note 2. See Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s The Cleft Stick (1937).

Note 3. Mr Hulkington’s grocer’s shop is at the centre of ‘The Little Gold-Mine’, The Cleft Stick (Selwyn & Blount, London, 1937), pp. 79-106. All subsequent page references are to this – the only – edition. My article above has a brief summary of the story of ‘The Little Gold Mine’, as well as the other fourteen stories in the collection.

Note 4. Mrs Nattle is one of the so-called (by newspaper reviews) ‘chorus’ of older women in the novel and play of Love on the Dole. In The Cleft Stick she appears in the penultimate story ‘The Practised Hand’, pp. 194-211.

Note 5. For an introduction to Dickens’ story see the Wikipedia entry: A Christmas Carol – Wikipedia

Note 6. p. 33 in the Penguin edition of 1996; all subsequent references are to this edition and will be given in brackets in the text.

Note 7. Crown and Anchor was a gambling game popular in the Royal Navy and also in the Army during the First World War. The banker in the game was statistically pretty much guaranteed a good return. See Wikipedia entry: Crown and Anchor – Wikipedia .

Note 8. Wikimedia Commons Image from Wikipedia entry about this poster: File:30a Sammlung Eybl Großbritannien. Alfred Leete (1882–1933) Britons (Kitchener) wants you (Briten Kitchener braucht Euch). 1914 (Nachdruck), 74 x 50 cm. (Slg.Nr. 552).jpg – Wikimedia Commons. See this British Library page for more information about this famous poster: ‘Your country needs you’ advertisement – The British Library (bl.uk)

Note 9. There were anti-German riots and looting in Salford in the days following the news of the sinking of the Lusitania. The Manchester Evening News reported the considerable disturbances in both Salford and Manchester on 11th May 1915 (p.5). Further reports followed over the next two weeks including the arrest of some local people who had been found with looted goods.

Note 10. The sinking of the Lusitania and the xenophobic outbreaks which followed are also recalled in There Was a Time – see pp. 103-6. Here the businesses attacked are Hoffman’s butcher’s shop and Scheiner’s draper’s shop. Mr Hoffman is a ‘naturalised British subject of many years’ standing’ and Mr Scheiner has painted ‘WE ARE POLES’ on his window, but neither is spared from being looted (pp.104 and 105). In this telling an unnamed woman may be another version of Mrs Harrop: ‘an old lady wearing … a threadbare shawl’.

Note 11. ‘ “The Pictures … Are Even More Stark than the Prose” (Sheffield Telegraph 2/12/1937): Word and Image in Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s The Cleft Stick (1937)’, Word & Image, Volume 36, 2020, issue 4, pp.321-342. The article is open access and thus free to read online. See Full article: ‘The Pictures … Are Even More Stark Than the Prose’ (Sheffield Telegraph, 2 December 1937): word and image in Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s The Cleft Stick (1937) (tandfonline.com)