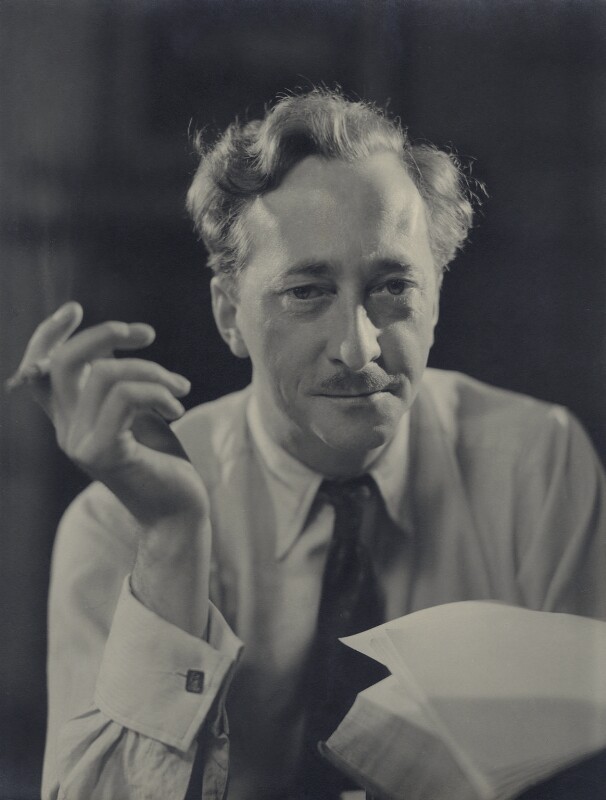

Walter Greenwood, by Howard Costner, print, 10 4/3 ins x 8 1/8 ins (273 mmx208 mm), photograph collection, NPGx1886; reproduced under a Creative Commons licence with kind permission from the National Portrait Gallery. For more on Howard Costner see: Howard Costner NPG Introduction

The photographer Howard Costner took a number of portraits of Greenwood, of which the National Portrait Gallery has eight. This is a characteristic image of Greenwood – always smart, and often pictured smoking. The photograph is not dated, but I think is probably from the early nineteen-forties.

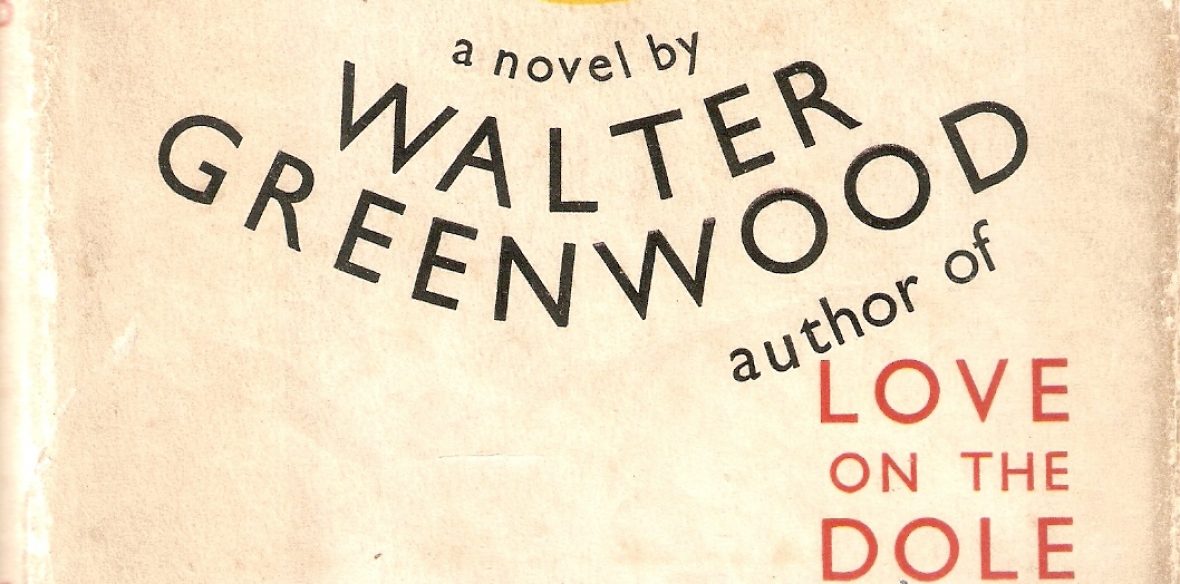

Walter Greenwood is remembered chiefly as the author of the novel, Love on the Dole (1933), and then a play-adaptation (1935), both of which had a wide impact on public perceptions of the intolerable living conditions of the unemployed in the nineteen-thirties. A few years later a film version (1941) was also a critical and popular success. However, there is also much more to his life-story and writing career which should be better-known. Greenwood came from a poor working-class background in Salford and after a variety of low-paid jobs, including working in a pawn shop, being a stable boy, working in a wholesale draper’s, repairing wooden crates, and being a clerk, he was unemployed from late 1929 till 1932 when he was employed in the rather miserable and ill-paid job of a ‘credit draper’s canvasser’ (that is collecting, when possible, the interest on clothing bought on the ‘never-never’ by Salford people who could not afford new garments in any other way). Though he was able to draw the dole for some of this period of unemployment, his benefits were then withdrawn after he had exhausted his period of entitlement under the rules of the time. His last job was as a typist at an extremely dubious property-company. When the Wall Street crash came in October 1929, his bosses disappeared suddenly, owing him three months wages. He took home the office typewriter in lieu and determined to write, both to tell the story of the people of Hanky Park, and to earn a living.

He wrote and sent off a number of short stories to fiction magazines, nearly all of which were rejected. His one success was a story called ‘The Maker of Books’, about a factory worker (based on an acquaintance) who decides to set up as an illegal on-street bookie, and loses his own money, his wife’s money and his mother’s money, but remains convinced at the end of the story that he’ll succeed if he keeps trying and can get his hands on some more cash. Though the story is surely about the perils of betting and hope, it also echoes Greenwood’s own feelings about trying to get into print: ‘In his way was he [Sandy] not like me basically … searching, like so many, for a way out of intolerable conditions? His desire was to make a book, mine to write one’ (There Was a Time, p. 205). The story was published in 1931 in the Story-teller magazine, which paid him what he regarded as the extraordinary amount of twenty-five guineas – a sum he reckoned as sufficient to live on – ‘a pound a week for half a year’ (There Was a Time, p. 215). Feedback from other magazine editors suggested that his work was insufficiently escapist – readers, they said, wanted, ‘romance, entertainment and excitement’ (1). Greenwood wanted to write about working-class life as it currently had to be lived. He specifically recalled being asked if he could write football stories – but he said he couldn’t, his heart wouldn’t be in them. (2)

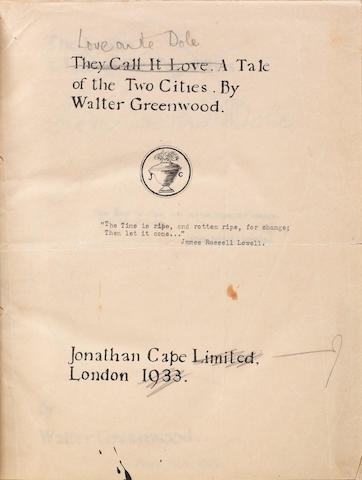

He also recalled sending off a number of novels to publishers and that the pile of rejected manuscripts was, he said later, at least proof of his continued practice. We do not know what kind of novels these were, though I wonder, just because I am not sure when else he would have had free time to write them, if they might have been his never-published historical-novel trilogy about industrial Salford, in which case one volume does survive, the other two being destroyed in the Blitz in 1940. (3) I think it is this trilogy to which Greenwood refers (though not by title) in his ‘Author’s Preface’ to The Cleft Stick in 1937 as ‘a vast, crude novel of noble proportions which now awaits the ministrations of a more practised hand’ (p.8). At some point Greenwood sent some of his short stories to the successful, popular (and socialist) writer, Ethel Mannin, to ask for advice on how to get them published. Her advice was that he should turn his short fictions into a novel, because she could not see a ready market for his short fiction (presumably because it was too serious, whereas this quality might be more marketable in a novel). (4) He followed this advice and reworked some of the characters from his short stories into a continuous long narrative, which became Love on the Dole (though he was still toying with the exact title even when the novel was in proof, as we know from a surviving corrected proof-copy which has two titles printed on variant pages, The Lovers and They Call it Love, together with the addition of the final Love on the Dole in Greenwood’s hand). I wonder whether it would it have caught the public imagination and had the same success under either of the alternative titles? (See image of final printer’s copy below from Bonham’s Auction Catalogue 24 June 2015: https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/22714/lot/262/ ).

Greenwood recalls nineteen-thirty-three being a wonderful year because Jonathan Cape accepted his novel – Greenwood quotes the letter as starting simply, ‘Dear Sir, We will publish your novel’ (There was a Time, p.249). Decades later Greenwood told his friend Thora Hird (admittedly over a glass or two of whisky) that he had sent it out to thirty-nine different publishers before it was accepted. (5) The novel quickly became famous as newspapers exhorted people to read it if they really wanted to know what it was like to be unemployed. The novel was unsurprisingly regarded as an authentic account of the misery caused for individuals and communities by long-term unemployment and poverty. The novel sold well and was reprinted many times during the nineteen-thirties and nineteen-forties, and has remained in print ever since. Both the literary qualities of the novel and its sustained publication history have made it the iconic British novel of the Depression. Its impact was also magnified by the play version (co-written with Ronald Gow in 1935) and eventually a film (directed by John Baxter in1941). Greenwood continued his writing career until the nineteen-seventies, publishing ten more novels, two non-fiction works, and a memoir, some seven plays as well as adaptations of his own work for radio and television, and a number of film scripts over the nineteen-thirties, forties, fifties, sixties and seventies. His last published book was his memoir, There Was a Time, in 1967, while his last stage piece was the theatre adaptation of the memoir, performed under the title Hanky Park in 1971 at the Mermaid Theatre, London. His work about British working-class life after Love on the Dole is undeservedly neglected, and indeed There was a Time is itself a notable working-class autobiography with all the vitality of Love on the Dole from thirty-four years earlier, and a more subtle narrative-style (though it traces Greenwood’s life only up until 1933, the year that novel was published). It is important to note that Greenwood’s later work often referred to or reworked Love on the Dole, so that this work – and its 1930s origins – were kept in readers’ minds from the nineteen thirties until at least the nineteen seventies.

Walter Greenwood was born on 17 December 1903 at No. 56 Ellor Street, off Hankinson Street, Salford (There Was a Time, p. 24). Hankinson Street was a poor area, created without the benefit of planning in the rapid urbanisation of the nineteenth-century and is accurately portrayed in the memorable opening of Love on the Dole. Walter’s father, Tom Greenwood, was a hairdresser and one-time music-hall singer who married Elizabeth Matilda Walter. Tom Greenwood died young, aged forty-five, in 1912, of chronic lung disease, probably assisted, according to Greenwood, by heavy drinking. Elizabeth came from a family with a strong tradition of socialism, union membership, and self-improvement. She had inherited her father’s book-case complete with its socialist book collection, as described in There Was a Time (p.172). However, no actual authors nor titles are identified, with the significant exception of Robert Blatchford and his very influential book of essays on socialism, Merrie England (1893). (6) I wonder if the bookcase also held a copy of Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (1914), which certainly influenced Love on the Dole in its conversion from short stories to a continuous narrative, and contributed to features of its working-class intellectual, Larry Meath. (7)

In contrast to the rich and varied working-class culture of his home life, Walter’s experience of education in Salford was wholly negative: ‘to me, the old School was a place to be avoided, a sort of punishment for being young … the handbell knelled us to punishment from 9 a.m. and 2 p.m.’ (8) There Was a Time records his being able gladly to leave school early (at thirteen) by passing the Board of Education’s ‘Labour Examination’, ‘open to fatherless boys’ so that they could help support their families by going out to work (p.107). Greenwood already worked part-time in a pawnshop and went into full-time employment there. He found it exceptionally dreary, leaving him ‘sullenly rebellious against the shop’s corroding tedium and its suffocating oppression’ (p.108). His mother found him a better job as a clerk for a seemingly ideal employer: the Pendleton Co-Operative Society. (9) According to an article in the Nottingham Journal (1/2/1935, p.12), for which Greenwood was interviewed, the building included a Co-Operative dairy, where he met Alice Myles in 1918. The article notes that Alice is now the manageress of the dairy and quotes Greenwood announcing their intention to marry shortly. This is not what happened in the end, as we shall see. Also, despite Alice’s presence, he was not much happier with the routine there than at the pawn-shop. Greenwood escaped from the Co-op by finding a job as a stable-lad at the house of a cotton- manufacturer (he had been reprimanded at the Co-op for decorating ‘account books and registers’ of members with ‘pencil drawings of horses’ – There Was a Time, 1967, p.128). However, as the depression kicked in, the manufacturer retrenched and Greenwood had to return to Salford to do a series of low-paid jobs – some manual, some clerical. As business after business went under, Greenwood joined ‘the growing brotherhood of the dole’ (p.184). His unemployment benefit was eighteen shillings a week – a drastic reduction to the family’s income. Greenwood later told his friend Bernard Miles that:

‘The family piano and much other furniture was sold under the means-test rule. Even the kitchen table went, and he did his writing on an old mahogany trouser-press’ (obituary, ‘Fame on the Dole’, Sunday Times, 15 September 1974, p.3).

However, this long period of unemployment gave Walter time for: ‘the ambition I had been nursing quietly for some time to try my hand at earning a living from writing. (p.185).

After the success of Love on the Dole, he firmly took up writing as his living and vocation. While the novel alone made him a celebrity, the play version greatly magnified his fame and the reach of his plea for something to be done for the unemployed and those living in sustained poverty. He was in fact approached in 1933 or 1934 by another writer, Ronald Gow, who suggested that Love on the Dole could potentially make a good play. The two met and agreed to co-write an adaptation for theatre (perhaps partly because Gow knew more about the world of theatre and had contacts, and already had one critical dramatic success to his name). They agreed that while making its serious points, the play must also hold and entertain an audience (making them laugh and cry), and not be ‘a high-brow piece’. (10) The play was first performed by the Manchester Repertory Theatre, with which Gow was closely involved, at the Rusholme Theatre (on Wilmslow Road, Manchester) in February, 1934. There was then a local tour – Gow noted that ‘a successful try-out in Manchester gave us the required confidence … to take the play into neighbouring towns’ (article in New York Times, 23/2/1935, p. XI). He recorded that the venues included ‘Salford, Sheffield, Birmingham, Wigan and all the other Northern cotton and pottery towns’ and that largely working-class audiences ‘realised that it was themselves they were seeing upon the stage, and that Love on the Dole was a slice of life – their own life’. The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette in 1937 (27 February, p.10) recounted the story that in February 1934 a well-known theatre agent was coincidentally detained in Manchester with a broken leg, and seeing Love on the Dole, immediately realised its potential and bought the rights from Gow and Greenwood. I am not certain, but it seems likely that this agent was Tom Vernon. The Manchester Evening News when reporting Vernon’s rather early death in February 1940 said that:

He was one of the men who saw the possibilities of the play founded on Walter Greenwood’s novel Love on the Dole. Putting a considerable amount of money into buying a share in the launching of the play, he reaped a rich reward when it ran successfully in London and on tour (22/2/1940, p.3, signed by George Mould).

His investment was surely a good one, and Vernon was a key figure in getting the play transferred to the Garrick Theatre in London. There it was a huge success, with three-hundred and ninety-one performances, presumably for a largely different kind of audience from the 1934 regional tour. The production made the name of the actress Wendy Hiller, who played Sally Hardcastle, and she also took that part in the likewise successful Broadway production which opened in 1936 at the Shubert Theatre. In addition, two separate productions toured British towns and cities between 1935 and 1937, and there were further productions until the outbreak of war in 1939. In short, the play was a phenomenal success, being seen, said Greenwood, by three million people by 1940 (letter to the Manchester Guardian, 26/2/1940). It is no wonder that Greenwood, who had lived on 15 shillings a week on the dole, could, in a rare public reference to his finances, later say that he had earned around £5000 in the year the play went to London (1935). (11) See Walter Greenwood’s Finances and Love on the Dole

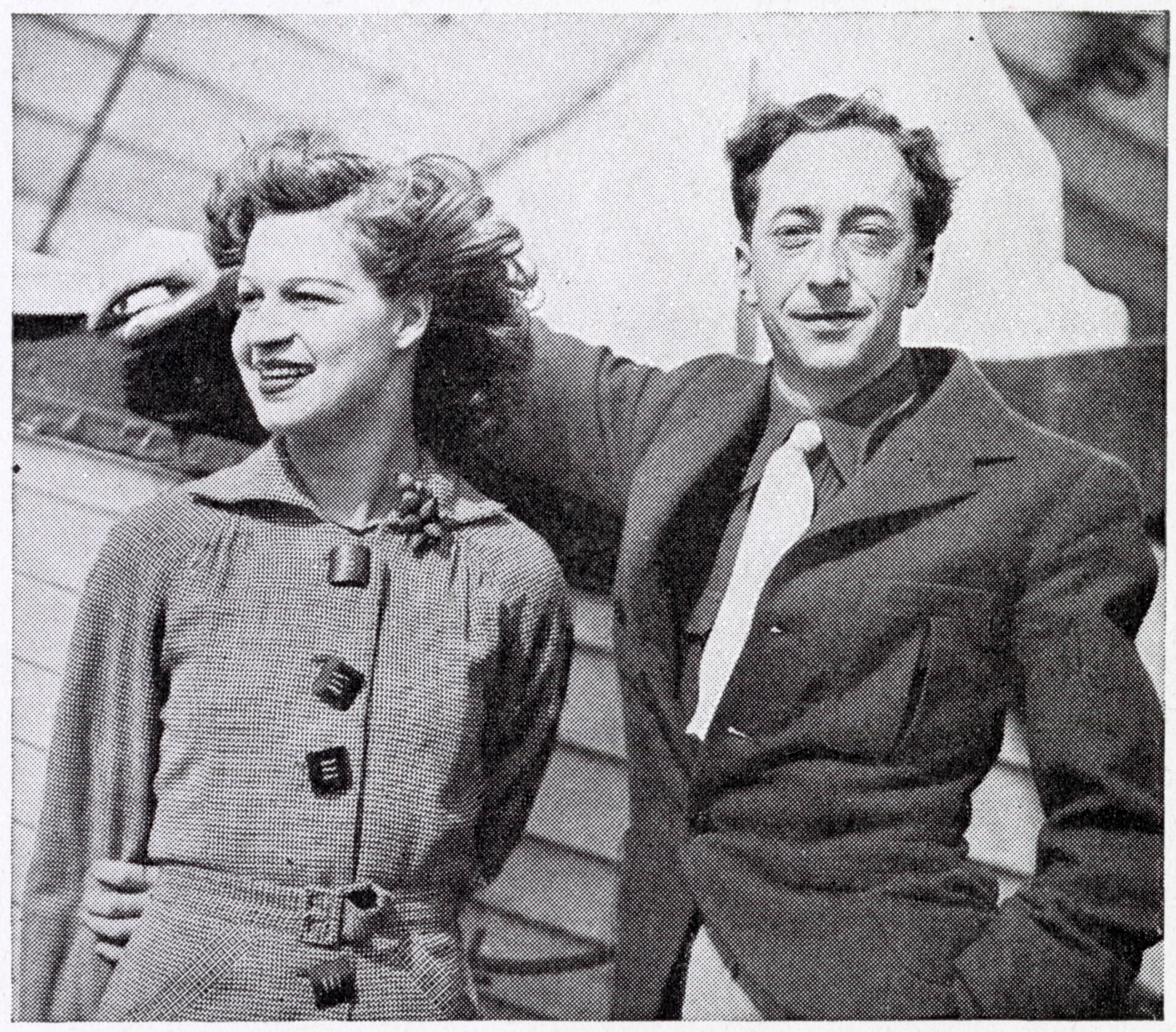

His private plans also changed during the period. Though he had known Alice Myles for a long time, since they were teenagers, and though in February 1935 he had publicly announced that they would marry soon, he broke it off by October 1935, and Alice sued him for breach of promise (a man withdrawing from an engagement could then be held to be breaking a contract, and therefore liable to legal consequences). He settled out of court (paying £700 and damages to Alice – a very considerable sum then), and acknowledged that he did have obligations to her. About six months later Greenwood met a US actress and dancer, Pearl Alice Osgood, at a theatrical party, while visiting New York in April 1936 to see the Broadway production of Love on the Dole. The two married in London on 22 September 1937, with their wedding much reported by the press (they divorced quietly in 1944).

Though their marriage was widely reported in 1937, there were few photographs published. Here are Pearl and Walter on the passenger liner S.S. Berengaria, returning the previous year from the States. The caption read: ‘Arriving in Southampton on the Berengaria, Mr Walter Greenwood and Miss Pearl Alice Osgood’ (from the Tatler, 22/4/1936, p.70; image is © Illustrated London News/Mary Evans, and reproduced with their kind permission). Walter does not at this point have his trademark moustache – unless it is pencil-thin on his upper lip!

In the thirties, he also wrote three further novels about Salford, all published by Cape, and all of which were widely read. First came His Worship the Mayor (1935) which explored not only the very poor of the city, but also its political elites in the form of local councillors, and their adequacy and willingness (or otherwise) to do anything actually to improve the situation for the poor. This was based partly on Greenwood’s own experience of being a Labour councillor in Salford during 1934 to 1935. Next was Standing Room Only or ‘a Laugh in Every Line’ (1936) which refers in a comic mode to Greenwood’s own transformation from unemployed man into professional writer. It tells of the experiences of Henry Ormerod, working-class author of a successful play, and his dealings with the world of theatrical agents and London theatres. Henry does make some money from his play, but not as much as others in the business. Greenwood’s next novel was The Secret Kingdom (1938), in several respects based on the lives of his parents in its story of an improvident and short-lived barber and his contrasting wife, a principled and self-taught socialist. Their son echoes Greenwood’s own success by becoming a classical pianist and a BBC radio star. For the first time Greenwood published two novels that year: the other was a gangster novel set in London, published by Hutchinson and called Only Mugs Work. Most reviewers did not think it a classic of that genre.

More of a hit was his only short story collection, The Cleft Stick, or ‘It’s the Same the Whole World Over’ (Selwyn & Blount, London, 1937), with striking monochrome drawings by the then celebrated artist and book-illustrator, Arthur Wragg. This drew on his early unpublished short stories, all about Hanky Park and with a number of characters who also featured in Love on the Dole. It was if anything, an even grimmer version of Hanky Park (though there is one story with a happy romance ending, ‘’What the Eye Doesn’t See’), and though too pessimistic for some reviewers, it was generally commended and seems to have sold well in both UK and US editions. It was often treated as a sequel to Love on the Dole, but actually twelve of the fifteen stories were written first, between 1928 and 1931, so it might also be considered as a prequel. While they inhabit an overlapping world, the two books have significant differences, and The Cleft Stick richly deserves re-publication as another of Greenwood’s most important works. The drawings (one for each story) by Wragg are also superb and an integral part of the whole effect. See Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s The Cleft Stick (1937) and Word and Image in Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s The Cleft Stick (1937)

Perhaps because he was pre-occupied with film work for his production company, Greenpark Ltd, which took on many commissions from government agencies, Greenwood published only one novel, Something in My Heart (1944), during the war. However, it was an important novel which was much noted and praised during the latter part of the war, and as Britain looked forward to a new kind of post-war society. The story opens in 1937 and initially concerns three main characters from Salford: Helen Oakroyd, who works in a textile mill, Harry Watson, and Taffy Lloyd, both of whom are on the dole. Indeed, this novel is a wartime sequel to Love on the Dole, which has been surprisingly forgotten. The first edition rear dust-jacket refers to Harry and Taffy as ‘two of that vast army of the unemployed’ who have now joined the RAF. The meaning of unemployment is thus shifted towards something more heroic than the dominant hopelessness represented in Love on the Dole. These transformations and modernisations of Love on the Dole are key to this wartime novel’s message. What was a call for help from the forgotten region of Hanky Park is here put into the larger perspective of ‘Act 2’ of the nineteen thirties, the road to war and thence eventually to the hoped-for post-war settlement for Britain. The novel asks if the State can intervene and mobilise social resources in wartime, why can it not also do so once peace is achieved? It was one of Greenwood’s contributions to shaping a debate about the shape of post-war Britain.

When the novel appeared in 1944, Greenwood was still very much in people’s minds. This was a result of his finally achieving a long-held ambition – to get Love on the Dole on the screen. Greenwood and Gow had first set out to do this in 1935 and had come to an agreement with the large and successful Gaumont-British company that they should make the film-version. However, all proposed British films were then sent before production started to the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC). There was no point spending money before it was clear if the film could be made, and the BBFC had interests in controlling cinema-audiences’ contact with quite a range of topics, including matters political, international, moral, religious and sexual. Most commonly, a short scenario or story outline was sent for scrutiny, but Greenwood-Gow-Gaumont sent the entire play-text (in the Cape edition), which two censors, Colonel Hanna and Miss Shortt, duly read. We know that the censors, whose reports are preserved at the BFI (British Film Institute) Reuben Library, found much to object to, both in the overall topics covered, and in some of the detail of the dialogue. The latter the proposers did not have to provide, but they may perhaps have felt that a published play which was currently touring, and widely available too as a novel, might carry with it considerable force as to its already-established public acceptability. As it was, even a simple scenario doubtless would also have alerted the censors to material unacceptable to their usual expectations. With slightly differing emphases, both concurred that without major alterations, a film version was impossible, despite the fact that the work could be read or seen in the theatre. This was essentially because they felt a more working-class audience might see the film version and feared they would be more easily influenced by what they regarded as controversial material. They objected to some sexual content (implications that sex outside marriage took place in Hanky Park, and Sally’s desperate deal with Sam Grundy), to bad language (probably profane use of religious terms), to the depiction of such depth of poverty in Britain, to the play’s political tendencies, and to the Means Test march scene where the police are seen striking demonstrators with their truncheons. We know from later press discussion that Greenwood consistently and repeatedly refused to alter any fundamentals of the story in order to make the film more commercially viable. Nevertheless, the following year, 1936, another film company, Atlantic Productions, proposed the film again to the BBFC. Again, they sent in the whole play-script, which Colonel Hanna conscientiously considered, and said, ‘I have read this play a second time, but cannot modify the first report in any way. I still consider it very undesirable’. (12)

There was intermittent discussion in the press during the later thirties about whether a film version might be on the cards again, and who might play Sally Hardcastle. In 1940, Greenwood showed he certainly had not forgotten about the way the film had been blocked, writing letters to the Manchester Guardian (26/2/1940, p.10) and the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer (27/2/1940, p.6) to protest against what he plainly saw as continuing unreasonable censorship. He especially put this in the context of the war, which he said British people were told they were fighting to defend democracy and freedom of speech. In fact, the Daily Herald reported on 27 February 1940 that the BBFC had yet again refused a proposal to make a film version of Love on the Dole. In 1941, there was an unexpected intervention from the Ministry of Information who asked the secretary to the BBFC, J. Brooke-Wilkinson, to contact Gow and Greenwood to tell them that they must make a film version of Love on the Dole without delay because of hints ‘from someone “higher up” ’. Sadly, the fresh BBFC censorship report which must have been written is in one of the few BBFC files which is missing. It would be good to know how it explained the sudden change of mind. (13) The film company British Lion produced the film, which was, after some false starts, skilfully directed by John Baxter, and rapidly completed under difficult war-time conditions in London during the Blitz (see The Film of Love on the Dole (1941)). Reviewers were impressed, often seeing the film as one of the best British films produced during the war. (14) Audiences also liked it and it played in cinemas throughout the war and after. Hence, Greenwood’s wartime novel of 1944, Something in My Heart, which argued that after the war the social conditions of the thirties must never be allowed again in Britain, readily picked up afresh, and for a new purpose, the concerns of Love on the Dole.

At the end of the war, and after, Greenwood worked on a number of plays, so that it was not until 1956 that he completed his next fiction project, The Trelooe Trilogy. The trilogy was set in Cornwall, where Greenwood was then living and was made up of So Brief the Spring (1952), What Everybody Wants (1954), Down by the Sea (1956). Reviews mainly noted the trilogy’s merits as entertainment. Nevertheless, all three novels show a strong sense of the changes brought about after the War: there are frequent references to increased taxation, the National Health Service, Nationalisation, and the Welfare State by richer and poorer characters alike. The three novels share a number of characters, but each also introduces new characters who interact with the population of the fictional Cornish village of Treeloe. As the language used in reviews of the trilogy suggests, it has many features (including happy endings for the good, and some pastoral tendencies in the depiction of Cornwall) which we might call middle-brow. Where earlier in his career, Greenwood is happy to use popular conventions allied with an urge for social reform, there is in these fifties novels less pressure from social issues, though there is always a running commentary on obsession with money as a perversion of a satisfying life. However, Treeloe is not idyllic – the fishermen have to sign on the dole to make ends meet, and for some in the new post-war order self-interest still far outweighs the collective good. The Treeloe Trilogy sold steadily and is still highly readable.

Walter Greenwood, by Howard Costner, print, 8 ins x 6 ins (203 mm x 152 mm), photograph collection, NPGx10688; reproduced under Creative Commons with the kind permission of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG licence 10688).

This photograph is again undated, but was used on the rear of the dust-wrapper for his novel Down by the Sea in 1956, perhaps suggesting that it was taken in the mid-nineteen- fifties, when Greenwood was working on The Trelooe Trilogy.

Greenwood’s final novel Saturday Night at the Crown is set entirely in a Manchester pub over the course of a single day, and its urban, wholly working-class setting makes it interestingly comparable to his pre-war fiction. It follows the fortunes of the landlord Harry Boothroyd, the barmaid Sally Earnshaw, the cook Maudie, and a number of customers, including the dominant Ada Thorpe and her husband (who does not get the chance to speak for the entire course of the novel), her son Bert Thorpe, and US troops from a nearby base. This is a story notably set in a new world of 1950s working-class prosperity. Some of the younger characters, such as Bert Thorpe, work in the thriving successor to Love on the Dole’s Marlowe’s works and are seen as able to live much fuller lives than their parents and grand-parents, including through access to the new popular medium of television. For further detail see: Walter Greenwood’s Other Books

As mentioned, theatre also took up much of Greenwood’s energy in the post-war period, with the production of several original plays including The Cure for Love: A Lancashire Comedy in Three Acts in 1945 and Too Clever for Love in 1952 (both had a number of BBC radio productions in the 1940s and 1950s). Two post-war theatrical friendships were important to Greenwood – with the actor Robert Donat and the actress Thora Hird. Donat directed and acted in The Cure for Love in its 1945 premiere before putting much energy into getting the 1949 film version made, while Thora Hird, who played Mrs Dorbell in that film, went on to act in other plays Greenwood wrote, including Happy Days (1959), which was written with her in mind. His last work for theatre – a stage version of his memoir There Was a Time (later produced under the title Hanky Park) – was performed in 1967 and revived in 1971. Equally, the theatrical career of Love on the Dole continued, with innumerable productions at larger and smaller theatres in Britain since 1945. The National Theatre listed the play in its One Hundred Plays of the Century in 1999 (15). There was a musical version produced at the Nottingham Playhouse in 1970 (book by Terry Hughes based on Gow and Greenwood’s play, lyrics by Robert A. Gray, and music by Alan Fluck).

Greenwood wrote a number of post-war feature-film scripts. These include the highly watchable The Eureka Stockade (1949) which had what might seem an uncharacteristic setting for Greenwood in 1850s Australia, but was focused on a key event in the development of Australia when gold miners suffering taxation without representation rebelled against the British authorities and eventually won democratic reforms. Greenwood visited Australia in 1948 to work on the script for this with the director, Harry Watt. More obviously characteristic in that it returned to the themes of co-operation between labour and capital discussed in Something in My Heart, was the 1950 film Chance of a Lifetime. This was directed by Bernard Miles and caused considerable controversy because of its story-line about the absolute need for co-operation between workers and management. While the film’s urge for consensus now seems moderate rather than revolutionary, film distributors were unable to see this and were unwilling to screen the film until Harold Wilson intervened. See Walter Greenwood and Film

Greenwood was also engaged with radio and in the new possibilities of television. Love on the Dole remained a firm favourite for adaptations during and after his lifetime, holding the record for the most-produced play in the BBC radio’s ‘Saturday Night Theatre’ programme, which ran from 1943 until 1996 (BBC productions of the play included six separate versions in 1942, 1945, 1949, 1955, 1965, and 1972, with further productions after Greenwood’s death, in 1980 and 1987). There was also a BBC TV production of The Secret Kingdom in eight parts in 1960, while versions of Love on the Dole were produced by BBC TV Sunday Night Theatre in 1960, by Granada TV in 1967, and again by the BBC in 1969. See Walter Greenwood on Radio and TV

Though Saturday Night at the Crown (1959) was Greenwood’s final novel, he wrote one further successful prose work: his memoir There Was a Time, published by Jonathan Cape in 1967 (its popularity was confirmed by a Penguin paperback edition later that year). It was praised as a twentieth-century working-class autobiography evoking a now unimaginable world. As in Saturday Night at the Crown, Greenwood felt confident here that much better times for working-class people were now irrevocably established:

Meritorious children of my contemporaries … are graduates of Oxbridge, Red-brick and the local school of Advanced Technology. Yesterday the Depression and lo! By a hop skip and a jump the Space Age and a Welfare State. A five-day, forty-hour week, holidays with pay, superannuation pension schemes, lunch vouchers and works’ canteens; an inrush of immigrants to fill the rising tide of jobs … and organised Labour in conference with employers on equal terms. (251)

He seemed less confident by the 1970s. In an interview for the Guardian with Catherine Stott in 1971, Greenwood is reported as ‘gloomily’ foreseeing ‘another slump just round the corner’ (‘Dole Cue’, 2 April 1971, p. 10). In an amateur interview with Greenwood filmed in Salford in 1973 he expressed the view that, overall, there had been ‘a marvellous change for the better’, and referred several times to the benefits of the post-war welfare state, especially improved child nutrition and health, and access to education. However, he regretted the loss of ‘neighbourliness’ and had sharp reservations about high-rise flats (14) Some of the footage is taken outside ‘Walter Greenwood Court’, the fifteen-storey-block built to replace the demolished Hanky Park area in 1964 and named in his honour. The block was itself demolished in 2001 after being used as a hostel for homeless young people (see Walter Greenwood Court (15 Storeys, 1964-2001 ) ).

Greenwood supposedly ‘retired’ to Kirk Michael on the Isle of Man in the nineteen-sixties, but certainly did not stop writing. In an interview with the Aberdeen Press and Journal on 27th October,1967, he said that he had very quickly written the stage version of his memoir, There Was a Time, on the Isle of Man, that he constantly took notes for new projects, and that he was currently working on a novel of contemporary Manchester to be called, It Takes All Sorts. The paper interviewed him partly to mark the world-premiere of There Was a Time at the Dundee Repertory Theatre (Greenwood said film would be the best medium for the play really, so he was clearly hoping for another adaptation too). There are a number of references to Greenwood’s novel in progress of late nineteen-sixties or early nineteen-seventies Manchester, and though it was not published for whatever reason, there are a number of draft manuscripts and typescripts of it at various stages of development in the Walter Greenwood Collection at the Salford University Archives.

The 1971 production of Hanky Park gave Keith Dewhurst an opportunity in the Guardian to look back over Greenwood’s career. He argued that he was ‘a writer of interest’ for several of his works:

but that with Love on the Dole he is far more’: he is part of English literature and of the history of English society and taste … [he] is not a great highbrow master like D.H. Lawrence, but he is and always has been a truly popular writer – a man of the people who entertains all sorts and conditions and appeals instantly and directly to their hearts (2/4/ 1971, p.15).

His obituaries were to take a similar view, though they sometimes under-estimated his artistry and the ways in which he carefully adapted literary and popular culture traditions. The Times said that: ‘his plays and novels owed nothing to modern, nor any other, theories of literature and drama. The stories he told, he convinced both readers and theatre audiences, were the inevitable result of the situations which faced the people he created. He was … a primitive, a literary equivalent to L.S. Lowry’. (16/9/1974, p.16). In 1971 Greenwood was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters by the University of Salford, to which his next of kin sold all the papers now forming the invaluable Walter Greenwood Collection. He died peacefully at his home on the Isle of Man on 11 September 1974, having spent over forty years of his life as a successful, popular, significant, and influential author of working-class origin. (16)

Note 1. Stott, Catherine. ‘Dole Cue’, the Guardian, 2/4/1971, p.10.

Note 2. ‘Author’s Preface’, p.9, to Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s short story collection, The Cleft Stick, or, ‘It’s the Same the Whole World over’, Selwyn & Blount,

London, 1937.

Note 3. The whole trilogy was called The Prosperous Years. We know about the destruction of two volumes because of a note written by Greenwood on the surviving manuscript volume (which is the second novel in the sequence). The manuscript is preserved in the Walter Greenwood Collection at the Salford University Archives: catalogue number WGC/1/1/1.

Note 4. From Mannin’s Young in the Twenties – a Chapter of Autobiography, Hutchinson, London, 1971, p. 143.

Note 5. In Scene & Hird – My Autobiography, Harper Collins, London, 1976, p. 261. See https://waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com/walter-greenwoods-creative-partnerships/

Note 6. See Wikipedia article on Blatchford: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Blatchford

Note 7. See Wikipedia article for information about Tressell’s novel: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ragged-Trousered_Philanthropists.

Note 8. From Greenwood’s ‘The Old School – an Autobiographical Fragment’ in The Cleft Stick, pp. 212 -222, p. 215 and 216.

Note 9. The branch of the Co-op they worked at is supplied from a different article with otherwise similar content in the Liverpool Echo (1/2/1935, p.8).

Note10. Part of a quotation of an interview with Gow in a TV Times article by Laurence Marcus, which introduced the 1967 Granada TV adaptation of the play, broadcast on 19/1/1967; located on the Television Heaven web-site in its Love on the Dole entry (accessed 2/2/2010; sadly, the web-site is no longer live).

Note 11. For more detail on the touring productions, see Chris Hopkins, Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole: Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, 2018, pp. 4-5; for some discussion of Greenwood’s finances see this blog article: insert.

Note 12. British Board of Film Censors Report 1936/87. For fuller discussion of the censors’ responses see Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole: Novel, Play, Film, pp. 141-6 and Jeffrey Richards’ The Age of the Dream Palace: Cinema and Society in Britain, 1930-1939, Routledge, London, 1984, pp.119 and after.

Note 13. See Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole: Novel, Play, Film, pp. 146-9, and Caroline Levine’s earlier excellent article, ‘Propaganda for Democracy: the Curious Case of Love on the Dole, Journal of British Studies, Vol,45 October 2006, pp. 851-65.

Note 14. Kersal Flats local history channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J1xr1UwLbQ0 ; accessed 26 October 2017.

Note 15. National Theatre Hundred Best Plays: <

<http://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/11741/platforms/nt2000-one-hundred-plays-of-thecentury.html>. 1999, accessed 16 July 2010.

Note 16. This biography is more concise than that in my book, but adds a number of pieces of information discovered since 2018, and is the fullest available online.