1. Greenwood’s Three Quotations from ‘It’s the same the whole world over’ or ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’

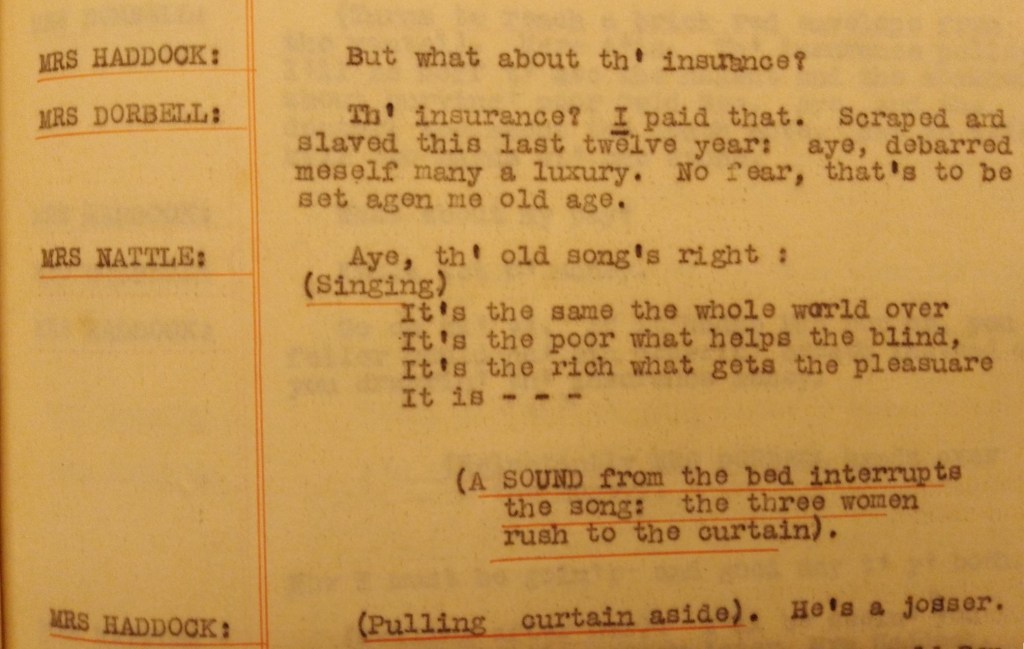

I should have noticed years ago that this popular song from 1930 meant something to Greenwood, but I didn’t. Firstly, it was not a song I knew (indeed, I didn’t know it was a song), secondly I tended rather negligently to ignore the sub-title of the 1937 The Cleft Stick short story collection, generally referring to it by that short title when the full title is really The Cleft Stick, or ‘It’s the same the whole world over’. Partly, this negligence was because I have something of a dislike of sub-titles for fictional works because they seem to me often to undermine or weaken the power and implications of the main title. I am a somewhat reformed reader now, because I see that this unexamined prejudice meant that I missed one plain clue, if another clue in the case was less obvious. However, I would never have picked up the three song references if I had not seen in the recently discovered typescript of Greenwood’s one-act play, The Practised Hand, that Mrs Nattle actually sings the refrain of the song in question during the play, providing new information in two forms: a reasonable chunk of the song lyrics and the explicit knowledge that it was a song. Here is Mrs Nattle’s version of the chorus in the play typescript:

MRS NATTLE: Aye, th’ old song’s right:

(Singing)

It’s the same the whole world over

It’s the poor what helps the blind,

It’s the rich what gets the pleasuare

It is . . . . [sic in text as she is interrupted by Ben the very ill and life-insured lodger dying] (p.14).

As we shall see, Mrs Nattle’s version of the lyrics of chorus is unique, but it is nevertheless unmistakeably the same song as that referred to in Greenwood’s short story sub-title.

Moreover, the same song is also referred to quite clearly in the novel of Love on the Dole too if with a quick reference which nearly passed me by. Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbell are early at the pawnshop to make their commission on neighbours’ items they are ‘obligin’ and have a conversation both about an immediate want and what they regard as an unpromising long-term political and social context:

‘Ah wish they wus open,’ Mrs Dorbell said; ‘Could jus’ do wi’ a nip, Ah could. Ne’er slep’ a wink las’ night, Ah didn’t. Daily Express is right. ’Taint bin same since war. Before that started things was reas’nable. A body could get a drink wi’out hinterference wi’ this ’ere early closin’ an late openin’. But Ah ne’er did hold wi’ Lloyd George nor wi’ any o’ t’ rest of ’em neither. Vote for none on ’em, say I. All same once they get i’ Parli’ment. It’s poor as ’elps poor aaaall world over.’ (p.33).

The relevant phrase from the song has my underlining – and I wonder whether the drawn-out ‘aaaa’ vowel is itself a sign that this was remembered as a sung phrase in origin? Mrs Dorbell’s specific complaint is about the fact that though it is dawn when the pawnshop opens, the pubs are not yet open. She is right that once they would have been open for workers to pop into briefly on their way to the Work’s start-time of six am. This need for drink (apparently for medicinal reasons) by the two women at all hours also matches their need as frequently expressed in the play of The Practised Hand, and their objections there too to the regulation of pub opening hours (see A Unique (?) Typescript Acting Copy of Walter Greenwood’s The Practised Hand, with Rehearsal Notes, and Two Character Sketches by Arthur Wragg (1935) *). Mrs Dorbell is also right in seeing this change as a relatively recent one since it was enacted very early in the First World War on 8 August 1914 as part of the Defence of the Realm Act (known as DORA – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defence_of_the_Realm_Act_1914 ). The rationale for this was to prevent drinking among manual workers which might interfere with efficient war production, so pub opening times were reduced from a free-for-all to just lunch-time and evening slots (from 11 or 12 noon till 14.40 or 15.00, and from 17.30 or 18.30 till 22.30). These regulated opening hours were continued indefinitely by a new Act of 1921 and only altered in living memory by new and less restrictive legislation in 1988 (though in 1977 in Scotland). However, Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle still might not have been pleased, since pubs still could not open until 11 am, until an even more liberal reform in 2005 (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alcohol_licensing_laws_of_the_United_Kingdom). Though no specific link is made to Mrs Dorbel’s introduction of Lloyd George as a good example of in her view an untrustworthy politician, there is almost certainly a link in her mind since he was a life-long teetotaller who publicly stated that alcohol consumption was damaging to the war effort and increased the tax on it as well as reducing the alcohol content of beer in the period when he held a number of key wartime government offices between 1914 and 1918, including as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Minister of Munitions and then Prime Minister (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Lloyd_George). There is thus lots of context for this relatively short speech, but you can perhaps also see why the song reference here did not originally leap out at me. What I have so far presented as song references do not look at first glance identical: ‘It’s the same the whole world over/ It’s the poor what helps the blind’ (short story) and ‘It’s poor as ’elps poor aaaall world over’ (novel). The song reference does not make it into either the play or film versions and is not in ‘The Practised Hand’ short story original either; though Mrs Dorbell’s explanation of why she will not pay for Ben’s funeral could well derive from the sense of the song, I do not think is quite verbally close enough to count as a reference: ‘When you’ve got nothing, you get nothing. That’s the way of this world’ (p.208).

The original song lyrics are these (first verse and refrain only; there were a further five verses, with the refrain repeated exactly) and the shared origin of both Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbel’s versions make their relationship clearer:

She was poor but she was honest,

though she came from ‘umble stock,

And her honest heart was beating

Underneath her tattered frock.

But the rich man saw her beauty,

She knew not his base design,

And he took her to a hotel

And bought her a small port wine.

It’s the same the whole world over,

It’s the poor what gets the blame,

It’s the rich what gets the pleasure,

Isn’t it a blooming shame?

As you can see, the two references by Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbel are somewhat mangled but recognisable from the original, though both (uncharacteristically?) introduce that idea that the poor help each other, which is not in the original song at all.

2. Billy Bennett’s Song (1930)

The song was known sometimes by a title based on the the words of the refrain, ‘It’s the Same the Whole Word Over’ – as when Greenwood names it as his Cleft Stick sub-title – but was also often referred to by a title based on the opening words of the first verse, ‘She was poor but She Was Honest’. The song has in some ways (and several senses) a murky history, of which the fullest account is given on John Baxter’s Folk Song and Music Hall site dedicated to ‘the intersection of folk and music hall, the songs and social history’ (and from where the above lyrics also come; readers can find the lyrics of all the verses there too). There do appear to be some versions, or predecessors, of a song like this dating back to around 1903, though the testimony to this also states categorically that the lyrics were too obscene to reproduce (the cited view and childhood memory of Maurice Wilson Disher, 1863-1969, in his book Victorian Song, Phoenix House, London, 1955, p.46). Greenwood would not have taken kindly to such a version and I shall ignore it too (and likewise what I gather are the equally and later obscene rugby versions). Moreover, in some sense the version of the song we are concerned with does seem to be a new (or anyway thoroughly cleaned) song with a clear publication date of 1930 by the songwriters Lee and Weston for their regular publisher Francis, Day and Hunter (though I have so far failed to find any copy of this as sheet music). Lee and Weston were a famous music-hall song-writing partnership who, as it happens also wrote a First World War song of which Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbel would surely have approved, but Lloyd George could not have done. Called ‘Lloyd George’s Beer’ the song gave a satirical account of wartime beer with the refrain ‘But the worse thing that ever happened in the war / was Lloyd George’s beer’ (see Note 1 below if you would like to listen to a recording of this by its first wartime singer, Eddie Mayne, from 1917). However, Lee and Weston’s ‘She was Poor But she was Honest’ was sung by another music hall artist called Billy Bennett (1887-1942) who was strongly associated with it and quickly recorded it on a 1930 78 rpm disk and then re-recorded a different version in 1932. In many ways the lyrics and their theme sound like those of a folk-song and so does the tune, and are sometimes sung as such, but they are not that exactly since they do seem to be of recent composition.

I think that Billy Bennett’s 1932 recording is rather superior to his 1930 one (due to the banjo accompaniment being rather faint in the earlier one) but will link to the invaluable YouTube reproductions of both in chronological order for the sake of accuracy and completeness. Here is the 1930 gramophone disk (you get the B side too with his song ‘Don’t Send my Boy to Prison’, but feel free to pause at will):

Here is the 1932 recording:

In line with this costuming, Billy Bennett was generally, as the title of this YouTube channel suggests, regarded as a comic singer and indeed, as his Wikipedia entry also suggests, he had a reputation for parodying dramatic monologues and Victorian-style music-hall songs. However, his performances of ‘She was Poor but she was Honest’ seem neither comic nor parodic to me but perfectly serious renditions. For interested readers I will later offer examples of some of the variety of ways in which the song has been performed, some of which bring out (allegedly) comic aspects while others stress rather its touching elements and its criticism of the status quo in terms of class and gender.

3. Greenwood’s Engagement with the Song (1933, 1935, 1937)

For the present though I will stick to the main task which is to record Greenwood’s evident engagement with the song. As we have seen from Mrs Nattle’s and Mrs Dorbell’s quotations from the song, Greenwood had no hesitation in playing games with it himself: both their misquotations have comic, and mostly grimly comic, aspects relating to how the poor interact not so much with the rich but with the poor. Mrs Nattle expresses the view that ‘It’s the poor what helps the blind’ at the very climax of her combined plot with Mrs Haddock and Mrs Dorbell to finish off a very sick old man in order to speed up the pay-out on his life-insurance. Her use of the song (which I notice she calls ‘the old song’ despite its actual recent date) surely displays her own moral blindness (to use that terrible old metaphor). Similarly. given her own ways of making a living out of the small-scale business opportunities offered by the poor, Mrs Dorbell’s assertion through song-reference to the essential self-help given by the poor to each other has an ironic ring coming from her. What then of Greenwood’s own application of the song-title to his short story collection in the prominent position of sub-title? (prominent even if it did take me fifteen years to notice it).

This will take more interpretation than his two characters’ shorter references since there are fourteen stories (and one autobiographical ‘fragment’) to which it should in some way apply, though perhaps not too literally to every story. Here are the titles of the fifteen pieces together with the shortest guides to themes which I can come up with (though despite myself they seem to get less concise as I go on – or maybe Greenwood’s plots got more complex?).

A Maker of Books. A time-clerk tries to make it as an on-street bookie to escape from life at the Works, and despite repeated failure and borrowing money from his family knows that one day his luck will turn and that he will escape Malowe’s works to become an independent businessman . . .

Patriotism. Women loot shops with ‘foreign’ names after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania by a German U-Boat in early May 1915; they especially target meat and clothing to express their patriotism. The looting is undoubtedly a revenge of the ‘British’ against the ‘foreigner’, but that is clearly a merely opportunist mask for a revenge attach by the poor on the (relatively) rich.

Mrs Scodger’s Husband. Mr Scodger, a diminutive blacksmith, is oppressed by his wife, including by her trombone practise of the one hymn she can play: he thinks a win on a bet may help him renegotiate their relationship, but this does not work out as he hopes.

The Cleft Stick. The menopausal Mrs Cranford is so desperately exhausted from looking single-handed after her unaffordable and innumerable children and completely unhelpful unemployed husband that she tries to kill herself – but lacks a penny for the gas meter. Clearly she is in an impossible and inescapable position – a cleft stick.

Magnificat. Amy is made pregnant by Dick Winningham, the professional male dancer at the Palatine Dance Hall, who then skedaddles; she is disowned by her parents, but – deluded? – thinks that she is blessed like the Virgin Mary and that all will turn out well as long as she has her own child, the only thing she has ever had which is wholly her own.

The Little Gold Mine. Mr Hulkington the grocer persuades Nance to marry him because he is – relatively – rich: she encourages him to drink himself to death on whisky so she can re-marry the young foundry-worker Harry Blake, only to find that he loves not her but only the profits from the shop.

Joes Goes Home. Old Joe, who wakes – or ‘knocks-up’ – everyone for work at dawn each morning with a wire-tipped pole is ill and told he must go to the Infirmary: he and all his neighbours know he will die there.

All’s Well That Ends Well. The widow Mrs Babson owns a chain of six fish and chip shops but is determined that her daughter will not marry back into the working-class in which the shop-owner herself started and thus ‘waste’ her property and class advantage; however, Mrs Babson is herself tricked by an apparently upper-class conman who is then sent to prison, while Elsie does marry back into their origin-class – though with the gift of one of the chip-shops to live on.

A Son of Mars. The brutal ex-sergeant-major Ned Narkey abuses his deprived wife and numerous children, spending all available money on drink and on other women – abused in their turn: he is a certain ‘model’ of masculinity but gets no come-uppance.

What the Eye Doesn’t See. A very unusual Greenwood story with a happy ending: there is a marital disagreement between a young couple about whether they go on holiday or put down a deposit on a new concil house – they cannot afford both. However, their mutual misery is resolved positively, in the short-term anyway, as they realise they cannot realistically afford a new council house anyway, so spend their spare savings on the much-wanted seaside holiday. The underlying deeper tension between Lily and Henry Carlow is sparked off by the dropping of a spoon as they clear the table: neither will pick it up and there it stays for some days, continually feeding their mutual resentment about this decision.

A Quiet Life. Stephen is appointed at an early age as a skilled copywriting and ‘enlarging’ clerk with special skills in handwritten legal manuscripts – though on a very low wage; he is happy at his craft as the year’s pass, despite poor working conditions and having to live alone in lodgings, but soon his penmanship is replaced with new typewriters and he is ‘let go’: spending his unoccupied and penurious retirement in a public park during the day, he catches pneumonia and dies (his landlady decides his set of pens is worthless and smashes them.

Don Juan. Don Juan is the metaphorical description of Danny Evans, a motor mechanic with – for these stories – an unusual variety of eccentricities: he is a dandy except that he always wear a cap rather than suitable hat, likes directing the traffic in the absence of a policeman, he steals and takes to bits any interesting piece of machinery whoever owns it – and hence has done short stretches in prison – and he is fascinated by women until they show any interest in permanent attachment, when he runs a mile; nevertheless he goes too far with one woman and though he plans to desert her, her brother turns out to be the champion boxer, Battling Barson, and he forces Danny to do ‘the right thing’ very much against his will (presumably landing his sister, Mary Barson, with having somehow to manage all Danny’s issues).

Any Bread, Cake or Pie? The boy Harry Waring is a bit of a bully and always hungry – and for good reasons, since his mother cannot supply enough food to satisfy let alone nourish her growing children. Harry and the other neighbouring hungry boys have a round of places where they try to beg (and if possible steal) food. The story simply traces their mainly failed attempts, and Harry’s bullying of what food they have even out of his hungry peers, but he still ends the story very, very hungry.

The Practised Hand. This is the origin short story on which the one-act play is based where Mrs Nattle sings her version of the song refrain. Mrs Dorbell has a long-term lodger Ben who is very ill, but seems to be taking a long tome to die – to his landlady’s impatience, after all she has been paying life insurance on him weekly for twelve years. Mrs Nattle suggests that the local midwife, Mrs Haddock, may be able to help speed things up, but only if he is really dying, and of course without doing anything wrong’. Ben does die very quickly and, while collecting on the death benefits, Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbell have to have a whisky to get over the shock of losing such a good tenant.

The Old School. This autobiographical fragment deals with Greenwood’s entire schooldays, such as they were, since he left to go to work aged thirteen. It details what he learnt, or rather what the poor did not learn at an elementary school, since he claims to have learnt nothing and to have felt simply imprisoned, as did the teachers.

I take it that the essential message of the song is that the entire world is organised unjustly, so that the advantaged take advantage while the disadvantaged bear both the penalties and the blame. Perhaps given the breadth of this message it would not be surprising if it takes in many of Greenwood’s stories, but I think it is a bit more precise than that in a number: in the majority of these stories those at the bottom stay at the bottom and suffer from that position while those with any advantage get away with it.

I note that in three of the stories the plot of the song is at root replicated: in ‘Magnificat’, ‘The Son of Mars’ and ‘Don Juan’ a man in a somewhat superior position takes advantage of a young and vulnerable woman (or indeed women) leaving her (or them) in a social disgrace and material poverty from which they cannot escape (though there is no suggestion of taking up sex work as in the song). Mrs Cranford’s narrative is broadly related too to this tale of men taking advantage of women: her experience might be said to be a life-long payment for the youthful mistake of marrying a man who could not keep her, yet made no attempt to limit his children, which makes the situation increasingly bad (indeed, as Mrs Bull tells her in the story the menopause, despite her current feelings of desperation, will be an end to her child-rearing miseries at least). While the song refrain phrases the universal opposition as between rich / poor we might also note that this maps onto male/ female in the song and in these four of The Cleft Stick narratives – and actually several others too.

It is true that this is not the only narrative pattern in the collection, but other stories explore comparable patterns of possession/dispossession and their persistence. Thus five stories are about the power disadvantages of different life stages: three about old age and two about childhood. ‘Joe Goes Home’ is about a man who as far as we know has always been blind but who takes on the essential (but surely poorly-paid) job of ‘knocker-up’, essential because the workers of Hanky Park cannot afford alarm-clocks but must, when in work, each make their clock-on time or be fined. His view of the job is that it has been a very good one, though it involves getting up before dawn in all weathers and seasons, and indeed he has probably become ill because of the life; however, Joe states that he will leave his knocking-up pole to Albert his grandson who in turn can take up this ‘rich’ opportunity. Joe is very sad to have to give up this life in order to enter the infirmary which for him (and all his neighbours) is exactly equivalent to entering the ultimate darkness of death. Part of the point of the story is that what seems a good life to Joe as he is about to leave it behind would seem a pretty poor, repetitive and hard life to many. Riches and poorness are in that sense relative states.

Something very similar forms the dynamic of ‘A Quiet Life’: Stephen Wain is quite content with his lonely, undervalued and underpaid life as a clerk, and is lost when he is dismissed in old age without a thought by his employer because the typewriter and changes in legal fashion have made him excess to requirements. He dies as he has lived, cold and alone and not a penny better off despite a lifetime of work.

In ‘The Practised Hand’ the lodger Ben is barely a character at all from the viewpoints of its other characters – he is merely twelve pounds and ten shillings life-insurance benefit waiting to be realised by Mrs Nattle on his death. He is a powerless victim of old age and, probably like Joe and Stephen, pneumonia. Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbell explicitly describe him as awkward for not dying more quickly – he has been ill for fourteen weeks – and only indulge in the luxury of treating him as human once he is safely dead and cashed in. Then Mrs Nattle remembers what a good lodger he was for thirteen years, who never gave any trouble. Mrs Nattle is not sure she will ever get over him, but Mrs Dorbell suggests a whisky will do them good at a time like this. Mrs Nattle accepts but laments that even so ‘you can’t forget a good lodger in half an hour’ (p.210). Of course, Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle are only relatively rich compared to Ben, but they certainly have the power to exploit him and indeed as it turns out the power of life and death which they turn to profit.

The two narratives focused on childhood equally show how those lowest in the pecking order fare the worst. Harry Waring is superior in size and physical strength to his school-age peers and he uses these advantages without scruple but he still cannot get enough to eat: he is always hungry. Though he does not see himself as a representative figure – on the contrary he acts always as an individual striving to survive as the fittest through competition – it is nevertheless clear in the story that all the children of Hanky Park are in a very weak position in a system where there is just not enough to go round. His mother – and the mothers of the other boys – do their best to get food and distribute it among their children, but as the boys are all aware their fathers are generable unable and/or unwilling to contribute. Harry takes this for granted; he finds his younger brothers and sisters crying on the doorstep:

He knew why they were crying. Why couldn’t his mother hurry with that washing, deliver it and get money for food? It did not occur to him to think of his father in this respect: his father was someone to be despised, someone who was always on the cadge for a pint of beer, who never worked, who slunk in and out of the house as a trespasser (p.185).

The fathers are not in any sense rich, but despite their own material disadvantage they still manage to derive some advantage from their traditional position in the gender / wage hierarchy, even if these are now reduced to pretty marginal advantages. They no doubt expect still to be given more than an equal share of food at family meals.

Walter’s own family situation is not quite the same as this, but his position of childhood powerlessness is a key theme in ‘The Old School’, where he blankly recalls his childhood as a ‘brutalised’ one (p.213) and school as imprisonment and punishment:

To me, the Old School was a place to be avoided, a sort of punishment for being young.

The teachers’ disgust of us was only equalled by our disgust of them and of the School. There was nothing at all of the Harrow-Eton alma mater affection. the handbell knelled us to imprisonment from 9 am and 2 pm. We were released at noon and 4.30 pm (pp. 215 and 216).

After his father dies suddenly (probably of tuberculosis and alcohol combined) Walter is allowed to leave school a year early, aged thirteen, having passed the Board of Education’s ‘Labour Exam’. He is delighted and immediately invokes the idea of freedom to express his release from prison: ‘I was free to find a full-time job’ (p.222). Of course, the retrospective adult Greenwood narrator as well as the reader may well read this ironically, especially given the state of employment in Hanky Park. In fact, he went straight to work full-time in the pawnshop which in his later memoir he, of course, also characterises as ‘a prison’.

Two more stories seem to belong together, the pair about shop-keepers in Hanky Park, who are that rare animal, individuals who have made a success of it and are relatively the rich rather than the poor. In fact, I think these both return with considerable twists to the ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’ plot. In ‘The Little Gold Mine’ Mr Hulkington uses his shopkeeper’s wealth to ‘buy’ Nance as his wife, though he knows full well that she does not find him at all desirable and that she wants to marry a young foundry worker called Harry. It is true that he does not plan to abandon her – but in fact she reverses their power relationship as soon as they marry and in reality abandons him, forbidding any marital relations but freely spending the money which the still doting older man gives her without restraint. Nance is perhaps now ‘Rich but Dishonest’, but is tricked in her turn. Harry Blake who in his thoughts is her idea love and desire agrees to marry her, but is fact is only interested in the profits of the grocery shop, and has to remind himself to pretend to love her. Nance soon realises what all his desires focus on – increasing cash flow – feels she can maintain a certain happiness as long as Harry never explicitly tells her he is completely uninterested on her. She has become the girl deceived by a rich man.

This too becomes, with another twist, the story pattern in the other shop-keeping story, ‘All’s Well that Ends Well’. Mrs Babson, widowed at an early age with a young daughter has through her own efforts built up a chain of six fish and chip shops (or what she calls ‘High-class Supper Bars’). Her greatest anxiety is that her daughter Elsie will fall prey to the lure of a poor working-class young man from the area who will pursue her and marry her not out of love but for the business, income and property she will inherit (as happens with Nance and Harry Blake). Instead Mrs Babson is intent that Elsie will marry a better class of man, who will of course be uninterested in her inheritance prospects and only in her self. This class-assumption is despite the fact that actually Mrs Babson herself comes from a solidly working-class background.

What Mrs Babson has not considered is any future prospect of romance, courtship and marriage for herself, since she is now aged forty. However, one day a very well-dressed and very-well-spoken car-salesman parks his equally smart car outside and asks if the restaurant can provide him with a meal. Both mother and daughter are smitten and rush to prepare food for him. The initial impression is reinforced when he gives then his ‘Royal Automobile Club, London’ card, bearing his name as Mr Hector D. L. G. Pritchard, and even more so when the is able to mend the vital gas-engine in their basement which drives their potato-washer and has unusually broken down (of course that is because when Hector is reconnoitring the job the day before he has temporarily blocked its external exhaust pipe). Hector soon lodges with the Babsons for a few days while working in the area, sells Mrs Babson a luxury saloon and in due course marries her. It is not quite the ‘She was Poor but Honest’ plot because though it seems obvious that Hector as a con-artist will take as much of Mrs Babson’s money as possible before disappearing, and leaving her at least poorer than she was, he in fact plans to make a permanent living out of the arrangement since he knew ‘that it pays to be honest when you are on good thing’ (p.130). However, things are rather taken out of his hands when it turns out that he already has a wife and three children elsewhere in Salford and is arrested and imprisoned for bigamy and desertion. Mrs Babson has been seduced by an apparently ‘rich man’ and is abandoned – and moreover left pregnant with an illegitimate child at the age of forty (that and the fate of her daughter and Harry Blake is tidied up at the end). The song story of ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’ has indeed been reused, if partly converted to a ‘She was Rich but He was Dishonest’ narrative.

That leaves us with just three stories unaccounted for. ‘The Maker of Books’ was the first story Greenwood had accepted for publication (in 1931) and I think not co-incidentally is the first story in The Cleft Stick. It was about gambling and Greenwood felt that his setting out to be a writer was in itself a risky gamble. The story is not obviously a romance or seduction narrative, except that actually one might say Ted is exactly seduced by a dream of riches:

To Ted the present was always stale, flat and unprofitable, the past reproachful and vain, but the future — Ah! In a word, he was as most men, ‘never is but always to be blessed’ (p.11).

He has the unshakeable conviction that if he just had one hundred pounds to spare he could become, like Sam Grundy, a successful book-maker. His widowed mother who has made a success of a small grocery shop absolutely refuses to lend him a hundred pounds for this purpose. She knows very well that with hard work you may be able to make a return on groceries but that you will never make a consistent return on the horses. Instead then Munter ‘invests’ the ten pounds his wife has saved despite her protests. Though Grundy has told him that bookies only ever run books and never bet themselves, Munter bets the money on horses to raise funds: he loses the lot. However, his mother dies and leaves him one-hundred pounds. His wife and friends urge him to take over the grocery shop and hold on to the money, but he does neither since he knows that with that much money he can set up as a successful bookie for life. He has usually regularly taken bets to Sam Grundy from workmates at Marlowe’s Works, but instead he begins to lay them himself. After losing on all these bets, he has to spend much of his £100 paying off his debts. Yet again ignoring Grundy’s ‘professional’ advice, Munter bets all the remaining cash on horses forecast to win by ‘Bendigo of the Sporting News‘ (a fictional racing pundit, p.22). Alas, Bendigo has a spell of poor horse-judgement, and therefore so does Ted: again he loses all his wherewithal. At the end of the story though, his hope is undiminished: he wishes he had used the £100 from his mother’s legacy to run a book rather than used it to bet, but thinks that if he uses what spare wages he has to bet on the basis of all the knowledge he has acquired from hs recent experiences then he’ll soon raise another £100 and can start all over again . . .

This is certainly a story about being in a cleft stick, if one of Ted Munter’s own making and stupidity, though perhaps we should see this rather as an addiction to gambling and to hopeless hope? In that way he personifies the qualities which Collette Colligan saw as typical of Hanky Park folk as a whole, a weakness for delusory hopes which nevertheless help sustain them: ‘the fortune-teller’s vision, the bookie’s promise, and the romantic dream’. (2) However, despite the cleft stick motif and Ted Munter’s dreams of riches I do not think that this story is really characterised at all by the ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’ / ‘It’s the Same the Whole World Over’ motifs.

Equally, ‘Mrs Scodger’s Husband’ also looks like an odd man (as it were) out. It is certainly about dominance, but not really about rich and poor, and the gender hierarchy is the contrary to that in ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’ and those Cleft Stick stories which resemble that song. Of course, it may be exploring the fact that men can have less power than women in some situations despite the prevailing gender hierarchy. Mrs Scodger has no doubt of her superiority to her husband, who, while his trade of blacksmith might leads to an expectation that he is powerfully built, is in fact ‘diminutive’. His wife seems to own all possible tools of superiority, including her physical size, her power over language and her utter self-belief:

Words, Mr Scodger knew, were useless: even had he wished to say anything he was powerless in the face of the self-righteousness which rendered him inarticulate. The enormity of her presumptive impudence was paralysing. (p. 44).

Finally, there is one more story which I think is not well-characterised by the ‘She Was Poor but She was Honest / It’s the Same the Whole World Over’ plots. This is ‘What the Eye Doesn’t See’. It is a story about choosing a more immediate satisfaction or a much longer term source of good: two weeks’ summer holiday on the Isle of Man or putting down a deposit on a house with, of course, the prospect of a long period of further payments. These possibilities or immediate versus deferred satisfaction for working-class people of limited means are a theme in the novel of Love on the Dole, where Larry Meath is unwilling to exchange a life where gramophone records and holidays are possible for a married one where there is not a penny spare, once he has lost his engineer’s job at Marlowe’s. Larry sees his male fellows in Hanky Park nearly always unable to resist the Irish Sweepstake or a bet with Sam Grundy, which offers an immediate pleasure but is based in a probably deluded hope of a longer-term gain. However, Henry and Lilian Carlow are not typical inhabitants of Hanky Park or The Cleft Stick stories, for they are not poverty-stricken, but managing on Henry’s job as a salesman in ‘a Manchester warehouse’ (p.151), and at least able to consider one day owning a house, and there is clearly equality between then in their relationship, so they are not at all candidates for a ‘ She was Poor but she was Honest’ plot. However, this makes them very unusual indeed. When they are temporarily fallen out both their mothers advise them as if marriage in inevitably a battle for dominance in a hierarchy and encourage each never to give in to the other or their defeat will be permanent. The trivial matter of the dropped spoon becomes a brilliantly used domestic symbol of disharmony as they are both aware:

All day they had dallied with the vision of a spoon uppermost in their thought: it was the representative symbol of all concerning the rift: to Lilian it meant a semi-detached villa on New Estate, to Henry it represented a fortnight’s holiday in the Isle of Man. For either to have picked up the spoon would have meant an acknowledgement of submission, a gesture of defeat. So it lay where it had fallen, on the floor. (p.154).

Things get worse: Harry says he will go to Man on his own, Lilian says if he does she will leave him.

Both regret this flare up and the whole spoon incident and think how much they love each other, but feel they cannot go back on their stated intentions. While Harry is out moodily and aimlessly walking the streets, Lilian is visited by an older married woman and her little son; their conversation makes it clear that Mrs and Mr Jack Roper are yet another happily married – and connectedly not hopelessly poor – couple from the neighbourhood. Both Mrs Roper and her son Stanley unwittingly do good works. Mrs Roper tells of how her husband Jack has been desperate to move to the New Estate but after getting out his pencil and paper realises that as well as the deposit they will need to pay twenty-five shillings a week for twenty years before they own the house. Mrs Roper has assured him that if they live on bread and butter and he gives up smoking they could manage that, but somehow the idea has lost its appeal. Then Stanley, naturally bored by such grown-up conversation seeks amusement and is rather bored by this overly-tidy house – until he finds a spoon on the floor and tries to ladle all the water out of a drain in the backyard, down which the utensil eventually disappears.

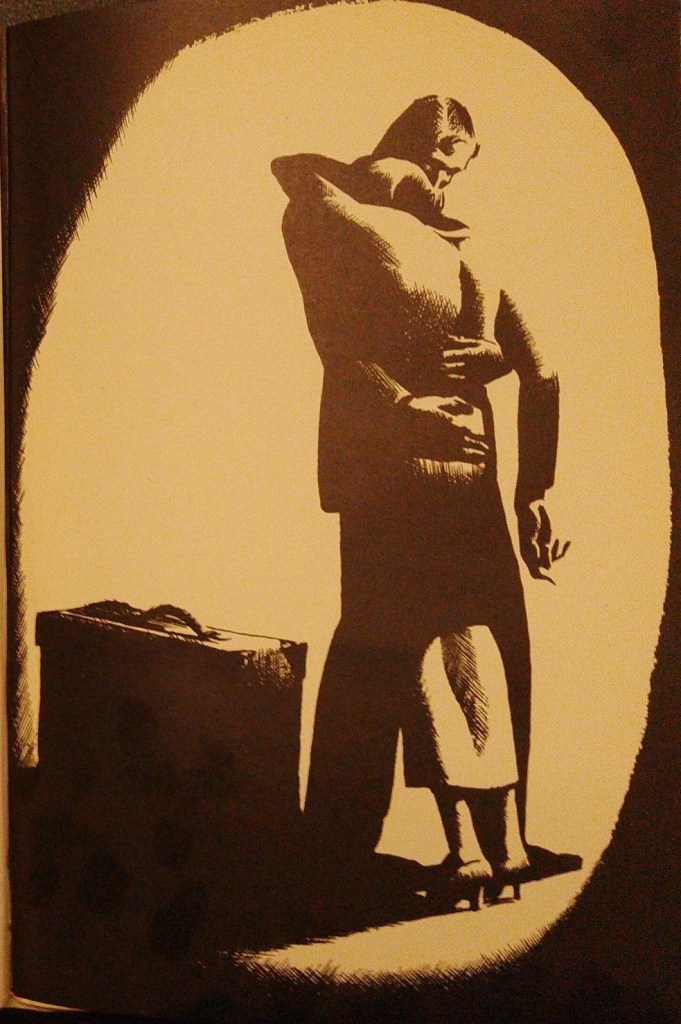

Each of the Carlows thinks the other has picked up that spoon, and anyway Harry is dying to tell Lilian he’d rather forgo the holiday for the eventual house, while Lilian is dying to tell Harry that they can’t afford the house and that they’d better pack their bags for a fortnight in Douglas. ‘The Cleft Spoon’ is thus negotiated and they go for the immediate pleasure: ‘Eeeee! We’ll have the time of our lives, Lil!’ (p.162). I have never discussed either this story or its illustration before, but with his usual brilliance this is how Arthur Wragg pictures that moment of reconciliation and happiness.

Overall, I think we can say that the majority of the stories in the collection are well-characterised by the ‘It’s the same the whole world over’ sub-title and its associated song-title ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’. A few of the stories fit less well, though perhaps all but ‘What the Eye Doesn’t See’ are well-covered by the overlapping implications of The Cleft Stick main title. It is perhaps surprising to find Greenwood referring to a popular song-title as the sub-title of one of his major and most important works – no-one has ever previously noticed that he did so.

4. Greenwood’s Musical Cultures

However, Greenwood was knowledgeable about music, having been bought up by his mother to appreciate both opera and other classical music. In addition, his father certainly advertised both classical music concerts and music hall artistes in in his barber’s shop:

My mother . . . now decided that my education at the council school was wanting in a most important particular – music. She had made a move already to correct this. Playbills from the local theatres were displayed in our shop and for this service, Father was given complimentary tickets. Those to do with musical hall were his preserve; drama in any form and, above all, opera, grand or comic, was Mother’s (p.59).

Mrs Greenwood also got Walter into the choir at St. Thomas’s, Pendleton (though very much against his will – he wanted to be out playing in the streets with his friends) and later arranged piano lessons. In fact, perhaps like most people, he had contact with a variety of musical cultures: throughout the memoir there are references to Greenwood’s experience of classical and popular music. Thus as a young man we see him attending as a regular concerts by the Hallé Orchestra at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, often conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham, and sometimes with free tickets provided by some customers at the café where Mrs Greenwood worked (p.120 and pp. 123-6).

Equally though we see Greenwood at various points partaking of other kinds of music in different ways. His fellow employee/prisoner in the pawnshop, Reggie Sniblo, offers a set of impersonations of music-hall stars, presumably including their songs in the case of singers: Gus Ellen, George Lashwood, Marie Lloyd and Harry Campion (p.88). In Harry Campion’s case Reggie actually sings the first verse of one of his most famous songs, and begins the refrain before his employer silences him by calling him to do some work (the square bracket in the lyrics below indicates where Reggie is interrupted and so where Greenwood’s quotation of the song breaks off).

Just a week or two ago my poor old Uncle Bill

Went and kicked the bucket and he left me in his Will.

The other day I popped around to see poor Auntie Jane

She said, ‘Your Uncle Bill has left to you a old watch and chain’.

I put it on – right across me vest

Thought I looked a dandy as it dangled on me chest

Just to flash it off I started walking round about

A lot of kiddies followed me and all began to shout,

Any old iron, any old i[ron, any, any, any old iron?

You look neat, talk about a treat

You look dapper from your napper to your feet

Dressed in style, brand new tile,

And your Father’s old green tie on

But I wouldn’t give you tuppence for your old watch chain

Old iron, old iron].

This very famous song was titled ‘Any Old Iron’ and Champion himself recorded it as early as 1911 (as well as on later occasions), so I will reproduce that early recording here.

).

Similarly. when very bored as a boy-clerk in the pawn-shop – and especially after Reggie Sniblo has joined the Army – Walter could sometimes secretly steal time to listen to music provided as pledges:

The doorless cupboard by the chimney breast housed pledges of an odd nature . . . [including] a solitary gramophone which had big horn. With this were a couple of single-sided records, vocal numbers, with orchestral accompaniment, by the Irish tunesmith Mr Michael William Balfe who, among other works, had to his credit the ever popular opera, The Bohemian Girl . . . stuffing a bundle down the horn I listened to muffled renderings of:

I dreamt that I dwelt in marble halls

with vassals and serfs at my side (p.96).

Inevitably the pawnbroker hears and stops this entertainment too as soon as he can. Balfe (1808 -1870) was a serious composer but had considerable popular success in Britain and Europe both with his operas and free-standing songs, some originating in the operas. ‘ I dreamt that I dwelt in marble halls’ was one of these, starting life in The Bohemian Girl (1843) but then becoming widely available as sheet music and in due course clearly as a gramophone recording (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_William_Balfe). Greenwood’s pawnshop memory dates to the First World War and I have found a single-sided disk probably from that period with the song sung by the US opera singer Mabel Garrison (1886-1963 – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mabel_Garrison and her discography https://www.discogs.com/release/16229721-Mabel-Garrison-I-Dreamt-I-Dwelt-In-Marble-Halls). However, she released two-sided recordings as well and I think the recording featured below is from a two-sided 1917 gramophone record by Victrola (641-A).

The memoir also recalls that during the war his childhood friend Hetty Boarder joins a music-hall troupe in which she becomes a star-turn singing a First Word War song which has not I think been well-remembered:

Serjeant Brown, Serjeant Brown, keep your eye on Tommy for me,

For he might go wrong on the continong when he lands in Gay Paree.

Parley voo as they always do when a French girl they see,

But if my boy Tommy wants to parley voo, let him come home and parley voo with me. (p.120).

In fact this is the refrain, and the song was clearly enough of a hit at the time to be recorded on this gramophone record from April 1916.

Greenwood’s memoir makes one further reference to a song written during World War One in its penultimate and climactic chapter 44, titled ‘Turn of the Tide’. Greenwood recalls the actual process of writing the novel of Love on the Dole, which dates the memory to 1932. It has been going well but then Greenwood runs into what sounds like a problem with the logic of the narrative rather than writer’s block:

Those are the happy moments in a writer’s life when a tale takes complete possession. For months this one had held me in thrall. Theme, characters and development flowed to within sight of completion, then, that curse of curses, a dead end and the frustrating and jeering challenge of an empty page (p.246).

To try to break through the vexing narrative knot, Greenwood starts repeatedly to walk round public spaces, including the cemetery where one day he hears singing:

Incongruously there floated to my ears the half-muffled masculine warblings of someone not at all displeased with life:

‘The bells are ringing for me and my girl.

The parson’s waiting for me and my girl’.

Clods of earth were being thrown out of a grave some yards away. The vocalist’s coat was folded and lying on a sack next a heap of salvaged wreath frames (p.247).

The singer in the grave (who surely will have reminded Greenwood of the grave-digger in Hamlet) is Walter’s impoverished boyhood friend Mickmack – who has finally had a lucky break and despite the very hard times of 1932 has got a job, as a grave-digger. This has made Mickmac, whom Walter has not seen for a while, extremely happy, for not only does he have a job, but is about to get married on the strength of it. Hence his choice of a song which reflects his mood and good fortune in being a grave-digger if not perhaps the situation of his job. Perhaps Greenwood sees the turning of the tide for Mickmac as a sign for himself too, at least in retrospect, for shortly after this strange meeting his narrative knot resolves itself:

One late afternoon on the third circuit of the public park’s perimeter, revelation, and the vexing problem was gloriously resolved and captured in scribbled synopsis.

My confidence was such that a little over a month before Christmas posted copies simultaneously to two eminent publishers, hoping that, before December 24th, they would be duelling fiercely with cheque books as weapons (p.248).

This is not quite what happened. One publisher, Putnam wrote back with praise but said they could not take the novel (see The Novel Putnam Published Instead of Love on the Dole: Hans Fallada’s Little Man, What Now? (Kleiner Mann Was Nun? 1933) *). However – a miracle – the other publisher, Jonathan Cape, said yes – a decision the firm surely never regretted.

Micmac’s song was one appropriate to his wedding plans and perhaps to Greenwood’s achieving his ambition to be a writer in its more general marking of a joy realised. The song with the verse ‘The bells are ringing for me and my girl’ was a US hit dating back to 1916 with the title ‘For Me and My Girl’ (not to be confused with the later and very similarly titled British hit of 1937, ‘Me and My Gal’ with music by Noel Gay). Here is a phonograph recording of Mickmac’s song.

The recording is four minutes and one second in length. Gratefully borrowed from the Modern Edison channel (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0NWPqHRZws&list=RDY0NWPqHRZws&start_radio=1) The lyrics are by E. Ray Goetz and Edgar Leslie and the music by Geoffrey W. Meyer (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._Ray_Goetz). The singer is Bill Murray (1877-1954 – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Murray_(singer)). I have not been able trace this recording but it may well date to 1916 when Murray was certainly making recordings. ‘For Me and My Girl’ was originally a stand-alone song but twenty-seven years later in 1942 it was revived in a version with a bit of added ‘swing’ by Judy Garland and Gene Kelly and was the inspiration for their movie of the same year (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bGlufdUslfA and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ShowRENlPs).

The memoir has quite a concentration of songs dating from the First World War but Greenwood in his other writings makes a number of knowledgeable references to nineteenth and twentieth-century popular songs. These include in the play version of Love on the Dole (1935) a part performance of a song called ‘The More We Are Together’, ‘Written & Composed’ (though ‘founded on an old air’) by Irving King in 1926. This was something of a hit in the mid-twenties, particularly as sung by (an apparently) Irish singer called Talbot O’Farrell (he had re-invented himself as an Irish singer in 1912, though born in Hull, and having performed in a Scottish persona as Jock or Will McIvor since 1902). Another hit briefly sung in the play is referred to by the title ‘For you’re here and I’m here, so what do we care’. The lyrics given are the refrain to a Broadway musical hit of 1914, properly titled ‘You’re Here and I’m Here’, with words and music by the very successful American songwriters Harry B. Smith (1860-1936) and Jerome D. Kern (1885-1945). It originally formed part of the musical The Laughing Husband, though in Britain also appeared in a revue called The Passing Show. Both of these songs are used, as is often ‘Its the Same the Whole World Over’, ironically with their upbeat messages and tunes sung at inappropriate junctures by – again – the chorus of older women (for fuller discussion and recordings see Two/Three Songs, Two Hymns, Two Socialist Anthems, and a March in the Play of Love on the Dole: Act I and Act III, Scenes 1 and 2 (1934/1935) (and a Coda on a Song in the Film, 1941) * ).

The film of Love on the Dole (1941) had neither of these popular songs but did use another instead. The song this time is one often called after the line at the beginning of its refrain, ‘Just a Song at Twilight’. Strictly, the song’s title is ‘Love’s Old Sweet Song’. The lyrics were written by Graham Clifton Bingham, who then sought a composer to write the music – several offered melodies, but Bingham chose that offered by James Lynam Molloy (1837-1909 – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Love%27s_Old_Sweet_Song). The song was published in 1884, but became a hit quickly and retained its popularity well into the twentieth-century, so it will have been immediately recognised by Love on the Dole cinema audiences. I think it is indeed a fine tune, though over time its sentimentality has often been subject to parody.

Greenwood refers to an older song again in his documentary work How the Other Man Lives (1939) in the section about life in the workhouse. ‘Seventy Years in the Workhouse’ bears witness to literally a lifetime spent in the workhouse system. It mainly draws on the testimony of a now elderly woman, but first in the opening section recalls Greenwood’s boyhood perceptions of the workhouse and the pauper. The very first lines of the piece are two lines from an entirely relevant song, which Greenwood says the children of Hanky Park sang whenever they saw the clearly distinctive ‘workhouse hearse’ pass by:

‘Rattle his bones over the stones, he’s only a pauper who nobody owns’

was the song we kids used to sing when the workhouse hearse drove through the streets (How the Other Man Lives, p.77).

The song is a setting of a poem called ‘The Pauper’s Ride’ published in 1841 by the poet Thomas Noel (1799-1861). It was first set to music in the 1840s by the popular composer Henry Russell (1812-1900), and then again by the also popular composer Sidney Homer (1864-1953) in his Three Songs of 1908. In either case it seems entirely possible that Greenwood and pals knew the song (though since the Horner version was more recent and was released on a 78 Victor recording in 1913, perhaps this is the more likely source?) (for fuller discussion and a recording of the song see Walter Greenwood’s Workhouse Memories (1933 to 1967) * ).

5. Some Conclusions (including about Love on the Dole)

Clearly, ‘It’s the Same the Whole World Over’ / ‘She Was Poor But She was Honest’ had lodged in Greenwood’s ear / mind at some point and resonated as a summing up of some of what he was trying to say about life for the poor in Hanky Park. Curiously, a review of Greenwood’s second novel, His Worship the Mayor (1934) was headed by the first line of the refrain of the song: ‘ It’s the Rich that Gets the Pleasure’ though the song is not directly referred to in that novel, so the theme of the song and Greenwood’s interests clearly chimed for the reviewer too, who was the Manchester novelist Howard Spring (Evening Standard, 20 September 1934; no page number, included in the clipping in Greenwood’s Press-Cuttings Book Volume 1, the Walter Greenwood Collection, Salford University Archives WGC/3/1).

That is really the final clue in the curious case of Walter Greenwood’s theme song, ‘It’s the Same the Whole World Over’ or ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’ except that I should end by observing that the ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’ plot is actually also key to the plot of Love on the Dole too, for surely the final part of the narrative where Sally agrees to Sam Grundy’s very bad bargain in order to save her family from destitution is also a version of the seduction / abuse of a poor young woman by a rich older man? Sally does not enter into the compromised situation naively nor willingly (indeed she repeatedly rejects his temptations and bribes), and she does make Sam Grundy pay, but nevertheless he exploits her because his wealth and position give him the power to do so (for further exploration of Sally’s unwilling arrangements with Grundy see Sam Grundy’s Car: Sally Hardcastle’s Resistance (1933;1941)* and for Greenwood’s later thoughts on the price she exacts see What Sally Did Next: Greenwood’s Sequel to Love on the Dole (‘Prodigal’s Return’, John Bull, January 1938) ). I speculate without a secure basis that this final plot development was Greenwood’s solution to the narrative impasse he had reached towards the end of writing Love on the Dole and which he was pondering as he heard Mickmac singing his grave-digging / wedding song.

5b. PS: Three Other Musical Interpretations of ‘She was Poor but She was Honest’ – Music-Hall, Folk, Swing (1969, 1962, 1940s?)

However, I did earlier promise readers with the musical appetite some examples of how different singers have interpreted this song and I can finally offer three different approaches from various dates: a music-hall version where a female singer as the protagonist tells her own story, a more folk-song-like performance, and to conclude a jazz-inflected version where the song is ‘swung’ a little. Here is Elsa Lanchester’s performance from a 1969 recording on a record titled More Bawdy Cockney Songs Vol II (Tradition disc 2091). I am pleased to say that I don’t think it is bawdy and that despite the odd comic touch it keeps the strong critique of careless rich men which is one of the song’s possibilities.

Here is the more folk-song style performance by Derek Lamb (though the record cover texts claims several different categorisations for its contents!). The refrain is again prominent and there is guitar, banjo and fiddle accompaniment to a version which is surely moving and again critical of the rich man and supportive of the poor young woman,

To end, here is a jazzy version sung by Ella Logan (1913-1969), apparently known as ‘the Swingin’ Scots Lassie’. The songs on the record are from the period 1932 to 1941, but I have not been able so far precisely to date this song – though I think it sounds more nineteen-forties than thirties. I very much like the blues kind of sadness Ella Logan gives it. I note that she replaces the word ‘blooming’ with the more daring and forthright ‘bloody’ in the refrain’s phrase ‘Ain’t it a blooming shame’. This performance again surely supports the victim and criticises the exploiter. For an introduction to Ella Logan’s career see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ella_Logan .

Clearly these three performances of the song are ones I rate, and which I think do the song’s words and music and potential meanings justice. I might be taking too much on my self, but I think Walter would have liked these versions. Curiously all were recorded during his life-time.

NOTES

Note 1. See details including the complete lyrics on the Folk and Music Hall site: https://folksongandmusichall.com/index.php/lloyd-georges-beer/. The site also includes a Youtube performance of the song by its original music hall performer, Ernie Mayne, which I have embedded here:

Note 2. ‘ “Hope on, hope ever. One of these fine days my ship will come in:” The Politics of Hope in Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole (1933)’, Postgraduate English, http://www.dur.ac.uk/postgraduate.english, ISSN 1756-9761, Issue 03, March 2001, pp.1-27, p.6. See https://waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/collette-colligan-article-on-hope-in-lod-2001-1.pdf. Colligan gives a thorough and complex analysis of how hope is both delusion and survival mechanism in Hanky Park and how this ‘doubled’ portrayal can fit with a critical socialist perspective. It is a very good article on Greenwood’s novel.