1. ‘The Present Continued to Inhabit the Shell of the Past’ (M.A Crowther, 1)

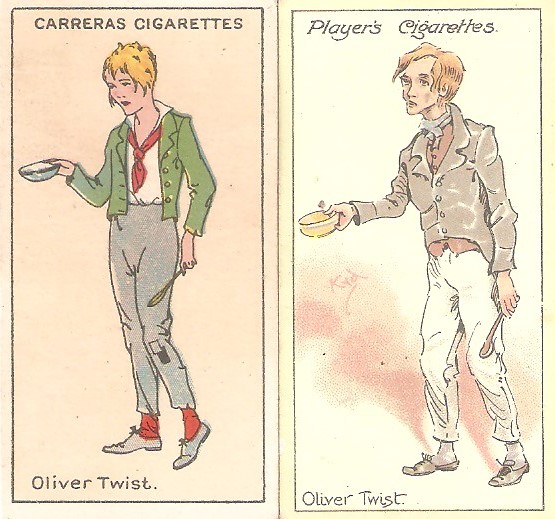

The workhouse is often most readily associated with the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including with Charles Dickens’ critical representation of the workhouse in Oliver Twist, (serial 1837-1839, novel 1838), a novel still of course being read in the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century by quite a wide range of readers, and which was remembered in popular culture, as in these cigarette cards. They focus on one of the most memorable episodes in the novel, when Oliver asks in the workhouse if he can have more gruel. As we shall see further on in this article, food was a big issue in the workhouse, and Greenwood and his characters often call the workhouse ‘the Grubber’, which highlights its role in feeding (in some sense) the desperately poor.

However, as we shall see the workhouse was not just a thing of the past or in classic fiction. It was still in the living memory and indeed experience of Greenwood and his parents and grandparents in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and thus in his writing. The section heading quotation above summarises the view of the long persistence of the workhouse by one of the leading historians of the workhouse system, M.A. Crowther: the phrase seems a key guide to the themes of this article about Walter Greenwood and the workhouse in its latter days. In some ways, what was left of the ‘workhouse system’ was residual, but it was still a large set of institutions and practices, and had real impact on large numbers of working people across England and Wales into the twentieth century. Even the word ‘pauper’ was not discouraged in official use until 1931. (2)

2. An Introduction to the Workhouse

The British workhouse system dated back specifically to legislation from 1834, though it had much older roots in medieval and early modern legislation for addressing (or anyway regulating) pauperism – that is to say a complete inability by an individual or family to support themselves. This was obviously a problem for the individual and the family, but also for wider society, and was seen as a source of harm and potential social disorder, including vagrancy and crime. The attempt to regulate poverty has been traced back as far as the Statute of Cambridge from 1388, which tried to restrict the movement of labour after depopulation resulting from the Black Death, but also implied a level of state responsibility for alleviating or anyway controlling the direst levels of poverty. The Wikipedia entry for workhouses cites research saying that the word ‘workhouse’ in the sense of a building dedicated to providing indoor relief in return for compulsory labour is first found in a document of 1603 from Abingdon in Oxfordshire (3).

The 1834 Act was often called ‘The New Poor Law’ and amended the somewhat elderly Poor Relief Act of 1601, which had itself updated the 1575 Poor Act, said by Wikipedia’s entry on workhouses to have first introduced the principle that those receiving poor relief must earn it through compulsory unpaid labour. The 1834 amendment was specifically a response to an increase in unemployment following the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. The new law was in many ways harsher (though more systematic) than earlier ‘Poor Relief’ under which some help could be granted to the poor living outside the doors of ‘workhouses’. The Act established Poor Law bodies called Boards of Guardians, who replaced the earlier parish overseers in running the workhouses established as part of the newly founded Poor Law Unions (a combining of resources by neighbouring parishes). The role and nature of Boards of Guardians were modified by an Act of 1894, but they continued to administer workhouses until 1930 – indeed, the Board of Guardians is an institution we will meet again in direct connection with Greenwood (for an introduction to Boards of Guardians in general see the Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Board_of_guardians).

The New Poor Law tried to reduce costs and absolutely to avoid making dependence on relief preferable to work for those tempted by what the better-off conceived as ‘idleness’ (a principle called ‘lesser eligibility’). Workhouse regimes were thus designed to be punitive and ‘indoor relief’ was indeed sought only by the utterly desperate who had no hope of surviving even at the lowest level of subsistence outside the workhouse. Nevertheless, the whole system was much criticised, partly by rate-payers who objected to funding it, but also by Chartists and Radicals fighting for reform, who regarded it as another tool in maintaining gross inequalities and the unjust social place of the better-off and the very wealthy. At a visceral and experiential level, the Poor Law and the workhouse were always dreaded by working people. Indeed the language of the workhouse system was clearly used by ordinary people even after official attempts to update terms like ‘the ‘workhouse’ and ‘pauperism’, so that this dread continued from popular memory into more modern times. The actual implementation of the nineteenth-century Poor Law legislation changed considerably over the course of the century, and the legislation was several times amended and its practical organisation reformed towards the end of the period. In particular, ‘workhouses increasingly became refuges for the elderly, infirm and sick rather than the able-bodied poor’ (Wikipedia entry, introduction, paragraph 3). In some of Greenwood’s references to workhouses (though not all) he clearly does intend institutions which have become in whole or part infirmaries, but that does not remove all of the history which the word ‘workhouse’ brings with it nor, as we shall see, the association with dread, shame, loss of independence, a sense of imprisonment, and even death.

Thus the workhouse system was still very much up and running for at least the first two decades of Greenwood’s life, with a number of aspects lingering on until reforms in 1929, 1930, and final abolition in 1948. In 1918 the Local Government Committee on the Poor Law recommended to the short-lived First World War Ministry of Reconstruction (1918 -1919) that workhouses be abolished and their functions taken over by other local government institutions. Nevertheless, it was a further eleven years before legislation followed which allowed (but did not compel) local councils to take over workhouses and convert them to infirmaries. However, the responsibility for workhouses was transferred from the Local Authority Board to the Ministry of Health in 1919, where it remained until 1929, suggesting an alteration in priorities at least (4). Some workhouses had already become infirmaries in the nineteenth century, but in any case the Act (The Local Government Act 1929) also included provision that the entire workhouse system be abolished from 1 April 1930 (though clearly some tidying up remained for the 1948 Act). At this point quite a number of workhouses were simply renamed ‘Public Assistance Institutions’ , though strictly speaking the term ‘workhouse’ had been already officially replaced by the term ‘Poor Law Institutions’ in 1913. (5) As we shall see, these several changes in terminology frequently did not percolate down to those actually in need of such assistance, who simply kept using the term workhouse. In the play of Love on the Dole (1935) the father, Mr Hardcastle, says as things reach a crisis: ‘We’re paupers, livin’ on charity. Dole or workhouse, its all t’ same’ ( Act III, Scene 1, p. 94). He may not be technically correct, but that is how it felt.

In 1929, the last year of the legal existence of the Workhouse/Poor Law institution system, there were still some 139,707 men and women living in the remaining institutions, of which 29.1% were in specialised sick wards, and 37.35% in general wards which might house the sick, those with mental health or learning issues, disabled people, the aged infirm, and paupers (the terminology of the time is unsurprisingly now problematic and I have modified it a little here towards something more modern though without losing the basic distinctions workhouse Guardians operated within at the time). In 1929:

In spite of all pressures towards specialised treatment, in the last year of the system more than 60 per cent of Poor Law inmates were still housed in the sick wards and general wards of unspecialised institutions. (6)

As M.A. Crowther makes clear, there was not simply indifference to this disastrously inefficient and inadequate policy of mixed wards: many medical staff and Poor Law administrators argued for the necessity of a range of reforms, but there was never sufficient investment to end these positively antiquated practices (for example, see Crowther’s discussion in The Workhouse System on pp. 98-100).

Whatever the complexity of the changing legal existence of the system and its relicts, its very real impact on those who had to engage with it continued, as did the collective dread of the workhouse for all working people. It is then not so surprising that the workhouse does indeed form part of Greenwood’s mental and fictional world (as well as the mental worlds of his parents and grandparents) and emerges from his writing a number of times across his oeuvre.

3. ‘Joe Goes Home’: an Infirmary Short Story (from The Cleft Stick, 1929/1937)

Greenwood’s first narrative about the workhouse dates back to the short stories he wrote while unemployed between 1929 and 1932 and was called ‘Joe Goes Home’ (first published as the seventh of fourteen stories in The Cleft Stick, co-produced with the artist Arthur Wragg, Selwyn & Blount, 1937). The workhouse in question has been transformed into an infirmary by the time Joe is admitted, so should be considered as part of the after-life of the workhouse system. Nevertheless, the meaning of the workhouse/infirmary to Joe, his family and his neighbours is made very clear as the extremely concise narrative of just two and a half pages unfolds. The title of the story is clearly deeply ironic.

The character at the centre of the story is known by everybody in Hanky Park as ‘Blind Joe Riley’. As well as in this short story, he also appears at the opening and close of the novel of Love on the Dole. This story tells you why everybody knows him:

They shook their heads, sadly recalling the innumerable years in which Blind Joe Riley, with his long pole tipped with a bunch of wires, clattered around Hanky Park of an early morning knocking on bedroom windows to rouse people for work. ‘Aye, all those years and years. It won’t seem the same whoever gets the job’ (The Cleft Stick, p.107).

Though Joe is at the centre of the story, and we do hear some of his thoughts when he speaks, for much of the time we hear much more of what his neighbours think, all ‘summoned’ to the street by the arrival of the ambulance come for Joe. All the neighbours are of one mind about what going to the infirmary means: ‘I guess it’s the finish of the old lad’, says one. Though Joe does not hear this, he unknowingly agrees and says so: ‘I’ll not come back from where I’m going, lass. When they send you to the infirmary, it’s dickey-up with you’. Mrs Bull (who as in Love on the Dole is ‘the neighbourhood’s uncertificated midwife and often unpaid nurse’) tells him he is wrong: ‘You’ll be out again in a month, fit as a fiddle’. Joe has no time for this false optimism:

No use o’ lying about it, Mrs Bull. I’ve seen too many of ’em go in there. And I’ve never heard of any of ’em coming out agen – not at my time o’life (p.108).

Before being helped into the ambulance, Joe makes his legacies: he gives his life savings of twenty-two shillings and sixpence to his daughter (the equivalent of £53 in 2024, according to the Bank of England Inflation calculator, not much over a working life of some sixty-one years), and his best pair of clogs and his ‘knocking-up stick’ to his grandson Albert:

That stick’s been in the family since my grandfather’s day. It’s a good regular business for our Albert if he looks after himself’ [in an age when pneumonia was difficult to treat, perhaps getting up six days a week before often damp dawns carried some heath risks?].

Once the ambulance has driven off with Joe deep within its interior, Mrs Bull puts into words what they all really think: ‘Ay, well . . . seventy-five’s not a bad age. And that’s how we’ll all go, one of these days’. The Infirmary can mean only one thing in Hanky Park, and that is death.

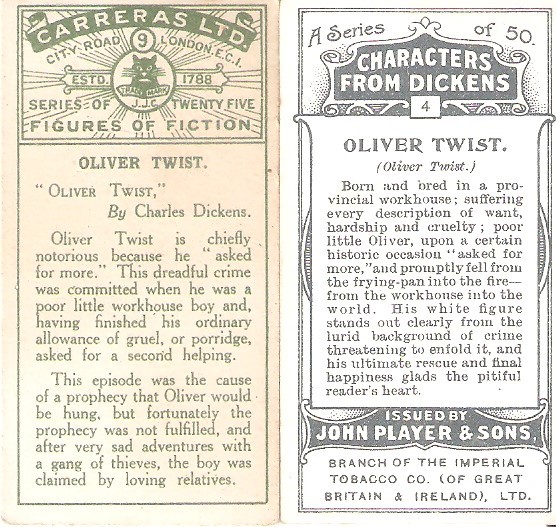

Since this story was finally first published in Greenwood and Wragg’s joint book, The Cleft Stick, there is also Wragg’s accompanying illustration which tells Blind Joe’s story very much in its own way.

As so often in this book, Greenwood’s stories are in a concise realist mode, while Wragg’s illustrations often introduce modernist elements (in a style influenced by German Expressionism, I think). As here, these techniques often bring together story elements which have a temporal sequence in the narrative into a single symbolic image concentrating the whole contents of the story, often together with an inner mental perspective from the character rather than an externally narrated view-point (perhaps doubly so in this instance because of Joe’s blindness). Here Joe is juxtaposed with his inner mental image of his whole life as a knocker-upper: the series of windows receding into infinity are not a literal depiction of Hanky Park streets so much as a surreal depiction of an endless repetitive series which has been his whole experience. The windows seem to tilt over Joe at work in a threatening way, and the static figure from the present echoes the past active self through his walking stick which has replaced his treasured knocking-up stick. It is a life which Joe can recommend to our Albert, but might seem very limited from a wider perspective. Still, it seems preferable to Joe to the darkness into which he is sure he will enter next. As so often in Wragg’s work, intensely dark areas (achieved in the original pen and ink drawings with repeated layers of ink applied with a brush) contrast with smaller areas of the white background paper and with the also large areas of minute cross-hatching. Here these contrasts of texture might suggest the darkness of Joe’s present as compared with his almost nostalgic view of his past life, which might nevertheless look harsh to others (even apart from the oppressive atmosphere of the apparently empty and lifeless buildings, the curling edges of the hatching suggest a cold wind swirling through the image against which Joe’s wind-blown coat and scarf are his only defence). (7)

There is a briefer reference to the workhouse in another Cleft Stick short story, ‘The Practised Hand’, and it has an even more direct association with death. That story concerns Mrs Dorbell who is very worn down by how long it is taking her very ill lodger, Ben, to die. It is a matter of pity, of course, though also of collecting the £12 10 shillings life insurance benefit she has taken out on him. In complaining of her (and his) protracted suffering to her neighbour Mrs Nattle, Mr Dorbell praises the approach she alleges the workhouse used to take to this kind of slow dying:

They ought to be given something to help ’em on their way. You know, like the black bottle they used to keep at the workhouse for the paupers. They weren’t allowed to linger in those days (p.198).

I know of no historical evidence for such a practice, but clearly it is an idea which impresses that frightening humanitarian and believer in insurance, Mrs Dorbell (for more about this grimly ironic story and play by Greenwood see Walter Greenwood’s Two Manchester Hospital Stories (1935 and 1945) * and A Unique (?) Typescript Acting Copy of Walter Greenwood’s The Practised Hand, with Rehearsal Notes, and Two Character Sketches by Arthur Wragg (1935) *).

4. The Workhouse in Love on the Dole (1933)

There are twelve direct references to the workhouse in Greenwood’s famous 1933 novel, showing its continued presence in the experience of poverty even at this late date. Ironically, most of these references are to what would have earlier been termed ‘outdoor relief’, the very thing that the New Poor Law was meant to work against. It is though also notable that the working-class young in the novel are not very familiar with the remaining adapted fragments of this ancient institution. The young people retain the fear of the name of the workhouse, but rely on those experts in relief, the older chorus of ‘entrepreneurs’ of poverty, to unlock the few remaining remnants of outdoor relief which remain.

The first reference to the workhouse comes some 164 pages into the novel (which is 257 pages in total) when the Mrs Hardcastle calls on Mrs Nattle to collect the money raised by pawning her wedding ring (she is wearing a brass one instead). Mrs Hardcastle has also to confess that she cannot afford to pay all of the week’s interest on Harry’s suit from the Good Samaritan Clothing Company. Mr Hardcastle has been laid off from the pit, which has closed, and Harry is still unemployed after nine months. Indeed only Sally is still working and she does not always get a full week’s work. In short the family are not managing and facing a real crisis. Mrs Bull observes that things are the worst she has ever known. Mrs Nattle is notably less pessimistic, because she is doing well (in a small way) from other people’s poverty, while Mrs Jike also feels more sanguine, though oddly enough it is she who introduces the theme of the workhouse.

Mrs Hardcastle shook her head as did Mrs Bull who concluded: ‘Ay, Ah don’t know what’s gonna come of us all. Ah ne’er remember nowt like it in all my born days and Ah’ve seen some hard times.’ Mrs Jike tittered: ‘We’ll all end up in workhouse. Somebody’ll have to keep us,’ with a bright smile: ‘It down’t do to look on dark side,’ offering her empty glass to Mrs Nattle: ‘Another sip, Sair Anne. While y’ve got it, enjoy it, say I. If it down’t gow one wiy it’ll gow another’ (p.165).

Clearly, Mrs Jike does not take the situation too seriously, presumably because actually she does not feel in too much personal danger. For her at this point the workhouse seems something of a joke (hence her ‘tittered’ pronouncement of the word), though beyond that there may be her fatalistic belief that somebody will have to take responsibility if the people of Hanky Park do become utterly impoverished. This does not suggest much knowledge of the origins and design of the workhouse as a deterrent to any such reliance on it as a safety-net. Her strategy of drinking to forget (while she can) shows her general lack of foresight and her avoidance of taking things seriously, though it is a kind of coping strategy.

As the novel moves on, references to the workhouse become more serious, as indeed actual use of it becomes much more likely for some characters. The next reference to the workhouse comes some fifty-seven pages later, and this time is named by the younger generation in a conversation between Harry and Helen Hardcastle about their near desperate situation – they are unmarried, she is pregnant, Harry is long-term unemployed, and they are both homeless:

She fell into step by his side, her troubled eyes searching his profile. ‘But who’ll tek us in, Harry?’ she asked, in a frightened whisper: ‘We’ve got nowt on’y what Ah’m earnin’ . . . An’ Ah’ll be confined soon. You’re knocked off dole, an’ there’s no room at our house . . . What’ll become of us? Oh, if only Ah’d known this was gonna happen . . .’

‘You leave it to me. Everythin’ll be all right. Ah’ll find a place for us, somewhere. Ah’ll . . .’ passionately: ‘Ah’ll join th’ army, afore Ah’ll be beat. Gor blimey, if Ah won’t.’

Either she did not hear him or her mild hysteria refused to be pacified. She kept mumbling to herself in whimpering tones while Harry continued, warming to the optimistic side of the picture: ‘ . . . Besides, when we’re married they’ll be bound t’ give us money at workhouse . . . An’ Ah’ll stand a better chance o’ gettin’ a job wi’ bein’ married (pp.222-223).

They next walk past the workhouse and then straight to the Registrar’s Office to get married without delay (Helen has borrowed the money for the Marriage Licence):

They paused outside the workhouse and stared at each other with expressions of shame-faced self-consciousness. Helen withdrew a ten shilling note from her pocket, limp with the perspiration of the hand that had been clutching it. She offered it to Harry: ‘Here it is, Harry,’ she said: ‘Ah borrowed it from a girl at mill. She says we can pay her back when y’ get work’ (p. 223).

The shame they feel is presumably compounded of a number of elements given their circumstances, but surely one is at the thought of having to seek workhouse relief – the mark of pauperdom which working people had dreaded throughout the nineteenth. century. There is no question though that they are paupers – completely unable to support themselves or the expected child through their own efforts.

Actually, despite his assertion that the workhouse ‘is bound t’ give us money’, neither Helen nor Harry know how to gain workhouse relief, and he has to ask Mrs Dorbell for her expert help. This she is very willing to give, though Harry does not at first understand on what basis. In a conversation with her gossips, Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbell, Mrs Bull observes of the latter that ‘by time she’s finished wi’ young Harry he’ll know all tricks o’ the trade’ (p. 227). This is true, but Mrs Dorbell takes offence at the implication that she will also take her cut – and rather illogically responds by asserting that she certainly will:

Nancy looked hurt and indignant: ‘They’ve got t’ give ’em their rent at workhouse,’ she protested, ‘no matter wot comes or guz,’ adding, warmly: ‘An’ Ah don’t see wot or why a pore, lone, widder ’ooman should go bout her due for sake o’ a young feller’s pride . . . ‘You betcha! Ah’ll show him the ropes. Nancy Dorbell’s lived too long t’ go owt short. Huh!’ (p.228).

Harry’s guess that the workhouse will have to give them their rent is thus borne out – and Mrs Dorbell is indeed willing to rent them a room, though that is only the beginning (’bout’ here means ‘without’). He is very grateful:

As for the workhouse, until Mrs Dorbell had initiated him he had no idea of the procedure necessary when applying for relief. He considered himself rather mean for having been ashamed to have been seen walking in the company of such a dirty old woman after she had taken so much trouble (p. 233).

Mrs Dorbell also introduces Harry to other institutions designed to give outdoor relief to paupers:

Never in his life until now had he heard of the ‘Mission to the Respectable and Deserving Poor’, from which organization, and after much questioning, he had received a layette and an order for a half-crown’s worth of grocery, printed on the back of which was a list of goods, classed as luxuries, which the shopkeeper was instructed not to supply (p. 233).

The two do not, though, always see eye to eye about the best use of such relief: Mrs Dorbell wants to pawn both the baby-clothes and the food-voucher (and as she frankly tells Harry she will buy herself a ‘nip’ with a small portion of her cut of the cash received from the pawnshop). Harry refuses to part with the layette which he is sure Helen will be pleased to have, but to express his thanks to his helper he does let her pawn the food-ticket. She tells him he has a lot to learn and is a ‘softy’ for he is not doing what she asserts every other needy family does in Hanky Park:

‘Yaaa, softy. Wot does a child want wi’ things like that? Ik’ll on’y spew all o’er ’em then they’ll be all spiled. Yaa, nobody about here e’er uses ’em. Allus they get ’em for ’s pop-shop,’ warningly: ‘Y’ll want as much money as y’ can get when she’s confined, lad’ (p.234).

Why on earth waste decent new clothes on a baby when these objects can be pawned for cash? Harry’s pauperdom and reliance on the workhouse is one of the factors which leads Sally to consent to Sam Grundy’s outrageous proposition that she become his unwilling mistress, as is clear in this stream of consciousness passage (not unique in the novel, but not its usual mode):

Brother a pauper: ‘They’re gonna gie me money at workhouse, Sal.’ Parents dependent on her; scratching and scraping until the distraught brain shrank and retarded and the mouth sagged and the eyes lost their lustre. And nevermore to see Larry. God, if only he was alive, half alive; anything if only he breathed, could look at and smile at her (p.242)

Most of the remaining references to the workhouse are on Sally’s part as she reflects on the depths to which her family have sunk and her own desperate decision to save them from this shame. There are, however, two final references by other characters: Mr Hardcastle and Mrs Dorbell. Mr Hardcastle threw his son out of the house for his irresponsibility in getting Helen pregnant when circumstances were already dire, but realises that actually he too has no choice but the workhouse:

These last few months since he had been knocked off the dole he had been living on Sally’s earnings. Living on a woman, his daughter, whom he had just dismissed for living on a man! She was gone now; had taken her income with her. What was he to do to meet the home’s obligations? The workhouse for pauper relief? He shrank from the prospect. Then there only remained Sally. And, to him, the source of her present income was corrupt. Oh, why the devil couldn’t they give him work? The canker of impotence gnawed his vitals. He felt weak; as powerless as a blind kitten in a bucket of water (p.248).

All the ‘choices’ Mr Hardcastle has are shameful – including the shame of having to turn to the workhouse. He knows that he can no longer draw any distinction between his own behaviour and that of Harry or of Sally. The powerful image of the helpless kitten drowning sums up his utter powerlessness, as well as the cruelty of unknown actors (the economic system and/or the response to it of the British government?).

Mrs Dorbell gets a last word on one of her areas of special expertise, the workhouse. Sally to her annoyance has helped Helen and Harry:

‘She’s a hinterferin’ young ’ussy, that’s what she is,’ snapped Mrs Dorbell, angrily: ‘It’s her doin’s as’s got me lodgers t’ tek th’ empty house at top o’ street. Aye, an’ him just startin’ work when he’d ha’ done me a bit o’ good. Me,’ indignantly: ‘Me, mind y’, as got him pay from workhouse an’ a parcel o’ clouts from t’ Mission. Yah! That’s thanks y’ get’ (p.252).

Sally has in effect helped Helen and Harry to regain control of their own outdoor relief, at least, so that they can subsist in a house of their own. Mrs Dorbell, as throughout her help to the young couple with the mechanisms of poor relief, dresses up her own money-making schemes as works of disinterested good-will and charity.

This portrayal in the novel of the workhouse makes perfect sense, but curiously shows as still active an institution which one might have expected to have been dropping out of the picture by 1931, when this part of the novel is set. However, as M.A. Crowther details, there was considerable continuity in the operation of both workhouses and outdoor relief during at least the early nineteen-thirties. Firstly, despite organisational and legal changes after 1929, neither buildings nor administrators of poor relief instantly changed:

In 1929 the Guardians’ powers were handed over to the public assistance committees of the county and borough councils. In fact, many Guardians kept their power over individual cases, for although they lost their powers to raise finance, the new committees were often Guardians themselves writ small. Instead of being directly elected, they were nominated by the elected councillors, who naturally tended to select people who already had experience of administering public relief (Crowther, p.109).

In addition, the very year of the most radical reform was also the year when the Slump began to bite deeply. There was little funding for new buildings or even radical reorganisation of existing resources, and anyway there was in effect a massive and sudden growth of those in or at risk of poverty or even pauperism because of the economics of the Depression:

Mass unemployment, concentrated in the regions of heavy industry, toppled the rickety structure of unemployment insurance and threw ever-increasing numbers of people on to the Poor Law. Outdoor relief had to be given, but the affected [Poor Law] unions could not cope administratively or financially, (8)

Experience quite soon showed that local arrangements could not address what was indisputably a national and international crisis, and in 1934 this was acknowledged with the formation of a new national government body, the Unemployment Assistance Board, so that the ‘unemployed finally ceased to be the concern of the Poor Law’ (which is not to say that unemployed people or their families no longer drew on its institutions). (9) The Unemployment Assistance Board (UAB) was not necessarily better funded, nor more humane nor any better regarded by working (and unemployed) people than its predecessor. Moreover, as we shall see, beneath it was another board for the even worse off, called the Public Assistance Committee, of which Greenwood was openly critical though also knowledgeable.

5. ‘Seventy Years in the Workhouse’ from How the Other Man Lives, (1939)

Though Love on the Dole was sometimes referred to as a ‘documentary’, the only really documentary work Greenwood did in prose (as opposed to film) was in his 1939 Labour Book Service commissioned book, How the Other Man Lives, which was made up of thirty-seven short sections about different contemporary occupations, each based on interviews which Walter had collected during 1937 to 1938 in Manchester/ Salford.

Two of these documentary sections are about the lives of those who have dealt with the workhouse during its long history or are from necessity engaged with its late thirties remnants. Both accounts give great insights into the legacy of the workhouse system, and its continuing incarnations during the nineteen-thirties.

‘Seventy Years in the Workhouse’ bears witness to literally a lifetime spent in the workhouse system. It mainly draws on the testimony of a now elderly woman, but first in the opening section recalls Greenwood’s boyhood perceptions of the workhouse and the pauper. The very first lines of the story are two lines from an entirely relevant song, which Greenwood says the children of Hanky Park sang whenever they saw the clearly distinctive ‘workhouse hearse’ pass by:

‘Rattle his bones over the stones, he’s only a pauper who nobody owns’ was the song we kids used to sing when the workhouse hearse drove through the streets (How the Other Man Lives, p.77).

The meaning of these lines is very clear: the pauper owned nothing in life, and in death is owned by no-one: there are no mourners because no one will miss him or her. I thought at first this might be from a Salford folk or street song, but in fact the lines come from a poem which indeed was set to music. The poem is called ‘The Pauper’s Ride’ and was published in 1841 by the poet Thomas Noel (1799-1861). It was first set to music in the 1840s by the popular composer Henry Russell (1812-1900), and then again by the also popular composer Sidney Homer (1864-1953) in his Three Songs of 1908. (10) In either case it seems entirely possible that Greenwood and pals knew the song (though since the Horner version was more recent and was released on a 78 Victor recording in 1913, perhaps this is the more likely source?). The lyrics of the whole poem/song entirely accord with the reputation of the workhouse, and with the remainder of this introductory section of the chapter in which Greenwood gives his childhood experience and brief mature reflection on that institution. Here is the first verse of Thomas Noel’s poem:

There’s a grim one-horse hearse in a jolly round trot, –

To the churchyard a pauper is going, I wot;

The road it is rough and the hearse has no springs;

And hark to the dirge which the mad driver sings;

Rattle his bones over the stones!

He’s only a pauper who nobody owns!

(see Note 11 below for the complete six verses of the poems).

Here too is a 1913 recording of the musical setting of the poem by Sidney Homer from which Greenwood and friends perhaps learnt their pauper chorus. (12)

This poem and song clearly match in mood and fact Greenwood’s reflections on the workhouse and pauperdom which follows in his prose:

We used to climb on to the cemetery wall and watch the coffins being taken out of the hearse, which itself was a long black coffin on wheels . . . I can see the graveyard drive now; a long long gravel drive through the clustered gravestones ending under this wall where the paupers were buried in unnamed graves. The curate or the priest, or both, used to gabble their words and clear off; there were no mourners, just a couple of men, undertakers’ men doing the job on contract terms . . .

The workhouse was the penultimate step before the grave for the aged, the infirm, the broken and the futile. From the workhouse they were transferred, when ill, to the workhouse infirmary; then, last scene of all, to one of the residences of him whose ‘houses last till doomsday’ (p.77).

The first paragraph reproduces much of what is expressed in ‘The Pauper’s Ride’ (so far I have not located an image of a pauper’s hearse), while the second echoes the view of the workhouse in ‘Old Joe Goes Home’ as the entrance to the domain of death. It is, it seems, a short step from workhouse to infirmary and thence to the third kind of building, the grave – which, as the first Clown in Hamlet (Act 5, Scene i) notes, will last till Doomsday (Greenwood knew his Shakespeare well and often quotes or alludes to Shakespearian texts).

Next Greenwood gives a visual memory of the workhouse he remembers:

The workhouse which I used to pass in my native city as a child was a grim, forbidding place, through whose half-painted, curtainless windows one saw in the dark of early evening the grudging gleam of a minute gas-light (p.77).

There were a number of workhouses (and cemeteries) in the ‘two cities’, so it is not easy to be certain of the geography of this reminiscence. In addition, we know that Greenwood and friends, like other working-class children in Salford, were generally left in what spare time they had to roam wherever they could walk to – adult supervision was not seen as at all necessary (for an example of a particular childhood expedition recalled see ‘Pendlebury’ in Three New Autobiographical Pieces by Walter Greenwood *). Greenwood’s description of the workhouse could easily apply to any of the workhouses established and used in Salford for various periods. However the likeliest match is the New Road or Salford Union Workhouse on the Eccles New Road, built in 1851-3 to replace grossly inadequate previous workhouses of various kinds (and, as we shall see, a reference to the Waverley pub being next door in fact confirms this as the setting of the testimony, as does the material from There Was a Time on the workhouse below in section 7). The Workhouse site has a full history and many useful images of the workhouses of Salford, including the Union Workhouse. (13)

From Greenwood’s own (rather external) boy’s memories of the workhouse and its deceased, the account begins to move to a more inward memory by someone who spent virtually their whole life there. Greenwood introduces the now elderly woman who is the centre of the substantial testimony which makes up this section:

Into this place in the year 1863, when the cotton industry was suffering from the effects of the American Civil War, was brought a two-year old girl whose mother, a worker in one of the local flax mills, had died of consumption at the age of twenty-one.

The little child was destined to spend the remainder of her long life in the institution. She was to outlive the workhouse, was to live to see it pulled down by a more humane city council which, in the place of the old building, erected a model home for aged people to which she was transferred. Now at the age of seventy-seven she looks back (p.78).

This is clearly a terrible story of a whole life constrained and determined by poverty, but there is also a more surprising narrative of improvement which contrasts with the Greenwood workhouse memories we have so so far examined. If the speaker lived in the Salford Union Workhouse then her account of the improvement in her conditions presumably partly relates to the building of a new and more specialised ‘old people’s home’ to the south of the Salford Workhouse Infirmary, to which she will have moved some time after 1924 (see The Workhouse discussion of changes over time to the Salford Union Workhouse). This would have taken her out of the generalised workhouse environment in which she had already lived (and worked without wages) for most of her life into an institution with a somewhat different regime and ethos. In this respect it shows the interviewee’s and Greenwood’s own awareness that there had been some changes (if piecemeal?) to ‘workhouses’ in the opening decades of the twentieth century. Greenwood carefully asks his witness to recall both the classic workhouse conditions she has experienced and the more recent improvements:

I asked her what her feelings had been when she had been transferred from the old workhouse to the new place . . .

‘Well . . . I can tell you, I didn’t like it at all. I cried for a month, But now I wouldn’t go back to the old House for anything. No fear. We’ve got nurses here. At the old House we only had attendants and they didn’t look after anybody . . . Ay, everybody here’s so kind. It’s all so different. You know, I never even want to go outside (p.78).

It seems likely that the speaker is partly from her own experience eliding more general improvements with her own change of status from adult workhouse inmate to old age inmate, but that is not to say that this does not also reflect some overall advances. The final sentence of this section of testimony about not even wanting to go outside may suggest a large degree of institutionalisation, something of which Greenwood shows awareness in his tactful questioning:

I did not forget that in spite of the frightful place the old building was, it had been her only home from childhood, that she had never known anything but its whitewashed walls and stone floors (p.78).

Nevertheless, her testimony about the old workhouse is damning. She recalls working for more than ten hours a day and suffering a serious industrial injury while falling asleep at a stocking-knitting machine. She recalls a monotonous and certainly inadequate diet always with one main meal a day and always of one course only:

Monday – ‘pea soup and dry bread’

Tuesday – ‘a bit of meat and three taters in their skins’

Wednesday – ‘suet pudding and treacle’

Thursday – ‘tater hash’

Friday – ‘rice milk’ [NOT of course as now a vegan milk alternative made from rice, but a kind of gruel of ‘milk boiled and thickened with rice and other ingredients’, OED sense 1]

Saturday – ‘tater hash again’

Sunday – ‘another bit of meat and jacket taters’ (p.80).

Eating habits and British cuisine have of course changed greatly since the interwar period, but this is evidently an extremely reduced version of an average working-class diet of the time: it seems especially deficient in vegetables and fruit, but probably also in vitamins, protein and fat, and even the main nutritional element, carbohydrates, is probably insufficient for men and women carrying out long hours of manual labour. Friday seems an especially thin day to our witness (‘and it was rice milk . . . there wasn’t a bit of sugar and nothing else in it’, though to me this sounds one of the more nourishing dishes, in terms of carbohydrates, protein and fat, if not necessarily tasty given the lack of additional flavourings, p. 80). Moreover, this was the unvarying weekly ‘menu’. This was presumably this woman’s diet for all her adult years until she moved to the new old people’s home – so perhaps from the age of fourteen till the age of sixty-four, a period of fifty years, from 1875 to 1925 (she was born in 1861). She also remembers that workhouse inmates had to wear a kind of uniform so that on the few occasions they did go outside everyone knew at once that they ‘lived at the Grubber’ (this is a word used in the novel of Love on the Dole to mean the Infirmary, p.211, but seems here to mean simply the workhouse in general – we will meet it again in section seven of this article). (14)

Greenwood’s witness also recalled a notable exercise of mindless and uncaring institutionalism when workhouse ‘economies’ were decided on (I do not know the date of this, but the building date of the pub referred to must mean it took place after 1875):

‘Turn me out, that’s what they wanted to do. They wanted to economise, so they said a whole crowd of us had got to go. The Board of Guardians it was who said it, and they gave us half a crown each, and said we’d to go and live outside. Yes, they turned us out into the streets with half a crown in our pockets and with nowhere to go. All of us, like me, with not a friend in the world’ (p.81).

Remember that our unnamed witness had been in the workhouse since she was two years old, and had never had an independent life nor income of any kind. The inhumanity and utter unreality of this proposed scheme, let alone actually carrying it out, should be beyond belief. But nevertheless, our witness found herself one day beyond the walls of the workhouse, having in a highly ironical sense been ‘set free’, and in a way expressed her co-operation with this granting of ‘liberty’. I reproduce most of what she says next because the rhythm of her story (possibly modified by Greenwood’s retelling of it) seems important to understand her peculiar situation at this moment:

‘What did I do?’ You May well ask. I’ll tell you what I did’. Chuckling, she leaned towards me and asked: ‘Do you remember “The Waverley” the public house opposite where the workhouse used to be? Well, I first called at the cake-shop close by, bought myself the nicest cake I could lay my eyes on, then I went off into the pub and called for a glass of whisky and change out of the two shilling piece I’d got left’. Again she laughed, unrestrainedly. ‘Enjoy myself? I never had such a good time in my life. I can see myself in “The Waverley” enjoying those glasses of whisky – I spent the whole of the two shilling – just as it might be yesterday’ (p. 81)

Having enjoyed this unique and self-chosen treat (what kind of cake did she choose to go with her whiskies, I wonder? I think a rich fruitcake might work well), our witness simply goes back to the workhouse and sits on the front steps. The workhouse staff (‘overseers’ she still calls them) pass her on their way home for the day and comment that she hasn’t gone anywhere – our witness agrees and says nor is she likely to. In due course the workhouse Master comes out to see what is going on, and sees he has no choice but to take her back into the workhouse. She is summoned to see the whole Board of Guardians the next week to explain what she did with her half-crown:

‘I’d the loveliest cake you ever saw and a few glasses of whisky to wash it down. I’d the time of my life and I’ve got to thank you all for it’ (p.82).

The Master later tells her that the whole Board was in howls of laughter as soon as she left the room, and clearly she is in no way reprimanded. It is an entertaining story, but more than that: it is the one autonomous act of her life, a form of rebellion which focuses just that once on her choice and her pleasure, and she never forgets it – telling Greenwood that she laughs aloud whenever she remembers it. The context though is a life without choices or autonomy – and even this little act of carnivalesque riot was forced upon her. The story too recalls Greenwood’s initial comment on her character that he was ‘amazed at her spirits, which in most people would have been broken long ago’ (p.78).

Our witness moves from this tale of the Guardians to further reflections about recent improvements: ‘Times have changed since then. We’ve got councillors now instead of the old Board of Guardians. And I say that they are all gentlemen, all of them’ (p.82). This clearly refers to the reforms of 1929, which transferred the administration of workhouses (strictly of course by then ‘Public Relief Institutions’) from the Boards of Guardians to the elected council, though this particular testimony has more faith that this resulted in change than does M.A. Crowther’s larger overview. Our witness is certain that the food situation was transformed, reporting that now:

‘Sunday they give us roast meat, potatoes and a vegetable. Pudding and a drink of tea. Yes, and on Sunday breakfast you get an egg. Why, I’d have fainted if they’d shown me an egg at the old House! Teatime we get tea, jam, bread and butter, And, what do you think? We get supper here every night. Cake and milk one night, and biscuits and milk the other. Why most of us wouldn’t get that if we lived in our own homes, Four meals a day! just think of that. And proper food too’ (p.82).

This does sound a great improvement in terms of likely satisfaction, as well as in terms of carbohydrate, fat, protein and vitamins. Our witness does not detail the weekly menu, so we do not have an exact comparison with the old workhouse weekly diet, but if weekday meals, like the Sunday dinner, included vegetables then that would have been a major enhancement of nutrition.

She also says that for the first time there are ‘amusements’ – something to nourish the mind and to allow those inside the institution to have a sense of ‘leisure’:

‘There’s the newspapers’ – she indicated two or three penny dailies lying on her bed – ‘I read ’em through every day to my bedmates. Then there’s the wireless. Ay, I don’t know how we’d get along without that.’ (p.83).

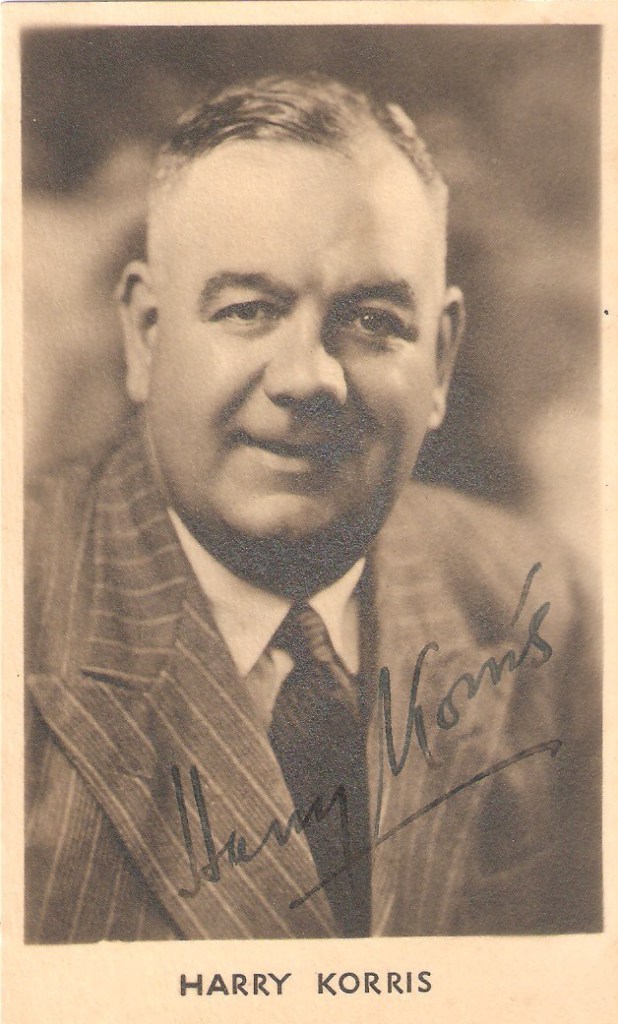

Presumably, not all her companions were able to read for themselves, but she can bring some external input into their lives by reading newspapers aloud. Greenwood asks her what she likes best on the wireless, and is told ‘Variety . . . Music Hall on a Saturday Night’, and especially the comedian Harry Korris. Korris (1891-1971) was a Manx-born comic in a northern music-hall tradition who worked on and behind stage from at least 1911 until he retired in 1950. However, he seems to have been at the peak of his career during the war years when he starred in the BBC radio programme Happidrome in which he played the part of ‘Mr Lovejoy, a harassed variety show manager and theatre manager’, as well as appearing in four film comedies about the Army, of which the first was Somewhere in England (directed by John. E. Blakeley, produced by Mancunian Films, 1940).

Korris’s Wikipedia entry says that he was only occasionally broadcast by the BBC in the nineteen thirties, but that he performed regularly live at Blackpool, and I think our witness must have heard regular BBC Saturday wireless broadcasts of his live variety spot there. Our workhouse witness gives him her highest praise: ‘He’s from Blackpool, and, oh, he’s a villain! Laugh! Well, whenever he’s on I laugh until I ache!’ (p.83). (15) A British Movietone newsreel (16 February 1942) featured Korris in his wartime role of Mr Lovejoy, and may give some sense of what cheered our workhouse witness in the nineteen thirties:

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KYOs1SXHkw, posted by Oop North 1 – 1 minute 49 seconds – laughter not guaranteed by the Author).

Radio is not her only possible outlet, for she tells Greenwood that these days the Workhouse pensioners can ride the trams for free and are also admitted into cinemas gratis. She has not been to see a film for a long time, but ‘years ago’ was very struck by a picture which she clearly recognised as portraying part of her own experience. She says it was called Over the Hill , and this maybe identifies it as the 1931 US movie of that name, directed by Henry King and produced by Fox Film Corporation (released in the USA November 29 1931). This version was an early talkie which remade the silent picture called Over the Hill to the Poorhouse from 1921 (directed by Harry Millarde, also produced by the Fox Film Corporation), though there was also an even earlier 1908 adaptation (directed by Stanner E.V. Taylor). I think our witness probably saw the 1931 picture because I imagine that trips out to the picture house were only permitted after she moved into old age ward after 1924 (though she does say she saw the film ‘years ago’ which imply a time before 1931). As the title of the earlier film makes explicit, the mother of a large family is at the centre of the narrative, and the climax of the film comes when she is left destitute by her grown-up children and has no choice but to go to the ‘poorhouse’ (the US equivalent of the workhouse).

Though our witness had seen the film probably some six or seven years ago (unless it was the 1921 version in which case it was some seventeen years ago), she remembers it sharply: ‘I cried and cried when they dragged the old woman off into the Workhouse. It reminded me of the old days’ (p.84). (16) Apart from being valuable as testimony about the Salford Workhouse, Greenwood’s interview also gives us some unique insights into the cultural experience and tastes of his workhouse witness.

Greenwood ends the piece by asking if there is anything under the new arrangements which could be improved. Our witness thinks it would be nice just to have a small amount of cash to spend as she chose – she thinks a shilling a week would be enough (her ten shillings a week old age pension is taken by the workhouse to help pay for her keep). This whole account is a very moving piece of testimony, recording some of the terrible elements of the workhouse system, and never losing sight of the deprivations of this individual’s life, while also testifying to her resilience and individuality and the impact on her and her peers of recent reforms. Greenwood probably offers these kinds of reform as at least in part a model for ways ahead, as an example of what humane reforms could do in local and national provision. The Local Government Act of 1929 was passed by Ramsay MacDonald’s (minority) government, with Liberal support, along with a number of other progressive reforms, so this context may also inform Greenwood’s good report of its impact, though this would not prevent him from elsewhere criticising sharply MacDonald’s later participation in the National Government of 1931 to 1935, or other aspects of poor relief.

6. ‘The Inquisition’ from How the Other Man Lives (1939)

Indeed, despite his workhouse witness’s good reports, Greenwood’s next account of relief arrangements in How The Other Man Lives is highly critical of arrangements after 1929, when ‘Public Assistance Committees’ took over from the old Boards of Guardians. This is made clear in his documentary section ominously and not at all neutrally titled ‘The Inquisition’. This documentary piece differs from the ‘Seventy Years in the Workhouse’ section in that though this is not explicitly stated I think the chief witness is actually Mr Walter Greenwood, Labour Councillor, in his (probable) capacity as an elected member of the Public Assistance Committee. This would date the testimony to experiences Greenwood had during 1934, the year when he was councillor for St Matthias ward, Salford. The piece does cite a number of other witnesses too, starting with what I think is another member of the Public Assistance Committee, though one with very different political sympathies (or lack of sympathies):

‘Are you aware,’ said the gentleman who had at least £3000 a year,’ are you aware,’ he asked me, indignantly, ‘that there are some men who get more from relief from the rates than they could earn at a job of work?’. He was of the ‘coals in the bath’ type of man, and, of course, he was wrong (p.144).

This ‘gentleman’s’ suppositions, based on the principle of ‘less eligibility’, chime exactly with those articulated in the Poor Law Act of 1834, a century earlier, which tried to ensure that poor relief always resulted in a worse living than that achieved by working (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Less_eligibility). Greenwood has no doubt that these suppositions are ill-founded. He puts into context the part played by the PAC (Public Assistance Committee) in a Britain which has seen considerable efforts since the early twentieth century to establish a new social security system to mitigate periods of unemployment through insurance while in employment. He also makes plain some continuities between the work of the PAC and the older workhouse system:

Generally speaking, the Public Assistance Committee’s ‘cases’ are those of men and women who have no ‘insurable record’, that is to say, they have never been employed in an insurable occupation. In the main they have been in the habit of earning a living as hawkers, newspaper sellers or odd-job men. Then there is that tragedy of ‘business recession’ – the black-coated worker, who until disaster overtook them, earned two hundred and fifty pounds a year or more and who, when he has sold everything that he had, is forced by sheer necessity to present himself to the Relieving Officer as a pauper in need of assistance from the public (p.144).

The PAC clearly caters for those in the least secure (indeed casual) and worst paid occupations, who are not covered by unemployment insurance and are therefore presumably at most risk of falling into pauperdom, though Greenwood also notes that due to the slump, ‘black-coated workers’ (such as clerks) can also easily fall into destitution. I note that he uses the word ‘pauper’ still, and indeed in the following paragraph talks still of the workhouse, though the year is 1934, when strictly there were no workhouses by that name at least. Greenwood explains that when a councillor is elected to the PAC he is given a booklet which offers guidance on how relief is to be administered:

One of these suggestions is that the able-bodied pauper who qualifies for assistance might be relieved to the tune of ten shillings a week, a similar sum for his wife and two shillings a week for each dependent child. Then again the Committee might decide to send the man’s wife and children into the workhouse while he is allowed to retain his freedom to search for work. This does not happen often in these hard times, since the workhouses are not big enough to hold all those who might qualify for them; it is cheaper anyway to give ‘out relief’ (p.144-5).

One notes the continued use of the term and institution of the workhouse for those at the bottom of the occupational hierarchy, though also that in fact there is so much pressure on the system due to the wider economic context that against the original intention of the workhouse system outdoor relief is often more viable than indoor relief.

Greenwood notes that deserving cases are often deterred by the belief that any connection with the workhouse is a source of the deepest shame:

The shame of their circumstances keeps many people away from the Relieving Officer. Over many years people have been taught to believe that a stigma is attached to money received from the city treasury . . . One man of my knowledge, a fine, honest type of work-man had fallen on evil days. He lived, with his wife, on a few shillings a week superannuation money . . .

He had been told that he could be relieved by the Public Assistance Committee but his reply always was: ‘Nay, I’ll starve before I go down there’. He almost achieved this (p.146).

Eventually, a friend of the man’s married daughter tells the Relieving Officer, who visits the man at home and persuades him that he is exactly in a position justly to apply for relief. On the other hand, Greenwood also notes from experience less justified claims (by the expectations of the times) including from men for households where they are not married to the female householder and for children who are not theirs. However, he argues that these kinds of behaviour though ‘deplorable’ are surely less bad than the practices of ‘rack-renting landlords’ who buy up cheaply blocks of slums houses to rent out exclusively to drawers of PAC relief in the knowledge that the PAC allowance for rent means the landlord will always be paid, even if he never has any intention of repairing the houses or addressing their damp and verminous condition.

Greenwood ends the piece by explicitly commenting on the effects of a National Government policy which for the destitute seems to run in a different direction to the 1934 transferral of the support of the unemployed to the national Unemployment Assistance Board:

One of the most expensive items in the budget of any city is the charge of the Public Assistance Committee. This has increased out of all proportion since the National Government threw the burden of the support of the unemployed on to local authorities and the depressed areas which can least afford it . . . A national pooling of rates is a remedy and one which calls for immediate adoption (p.151).

It is notable that here Greenwood draws on his own year of practical politics in local government to argue for a different national policy for the support of the poorest, the contemporary paupers who are still clients of the successor institutions to the workhouse.

7. Mickmac’s Grandparents from There Was a Time (1967)

Greenwood recalled in his memoir a day when his grandfather went to see the grandparents of Walter’s pal, Mickmac – a nickname derived from his family name of McBride, and presumably reflecting (not necessarily positively?) on the family’s Irish heritage. The whole McBride family was poor:

[Mickmac] was bow-legged, barefoot, scabby and one of a large family depending for its support on his father’s casual labour at the docks. The sign that things were exceptionally hard for them was when my mother fetched out the biggest of our three brown earthenware hotpot dishes, baked a huge potato pie in it, then took it to the McBrides concealed under a towel in our laundry basket (p.19).

The introductory description of Mickmac of course shows the symptoms which poverty has visited on him: he is bow-legged from rickets, a result of a vitamin D deficiency as a result of lack of sunlight and/or of dairy products such as milk; his scabbiness is likely be a result of the infectious skin disease, scabies, often arising from crowded living conditions, and his bare feet are equally a symptom of poverty: his family cannot afford the ‘luxury’ of shoes for their children. The memory dates to sometime before the First World War, and probably to the nineteen-tens. Greenwood’s grandfather is going to visit the McBride family to try to help the grandparents who are in a state of crisis (since they have been unable to pay their rent the bailiffs have removed all their furniture apart from the bed, the kitchen table and two chairs). Even the young Walter and Mickmac can sense:

The air of doom from the subdued conversation of the women congregated on the pavement near old Mr and Mrs McBride’s front door. ‘The Grubber. My God what an end’. The Grubber was the local name for the workhouse which, everybody feared, might be their ultimate place of residence (p.19).

Walter’s grandfather looks at the McBride’s carefully kept rent-book and their insurance book and has to tell their son that, though they have paid their premiums for thirty years, they have not been able to continue paying since old Mr McBride had to stop working, so that ‘the policies lapse and the company benefits’. I am uncertain exactly what kind of insurance is being referred to here, but certainly Greenwood’s grandfather, father and mother believe it might have saved the family from the workhouse, and are ‘indignant’ at their fate, as are the neighbours on the pavement, including Mrs Greenwood’s friend Mrs Boarder. However, their view was:

Obviously not shared by our corpulent next-door neighbour Mr Wheelam. Because of his position of authority in the mills and because he owned property locally he considered himself privileged. Listening to the comments from his doorstep he said crabbily: ‘I don’t know what you’re making all the fuss about Annie Boarder. They’ll be sure of a bed in the workhouse, won’t they? They’ll be clothed and fed, aye, and they won’t it have to pay for. Poor Rate, that’s where it comes from and property owners have to find for that’ (p.21).

Mr Wheelam is clearly not in sympathy with his poorer neighbours and is a kindred spirit to the ‘coal in the bath’ member of the Public Assistance Committee in my last section above. He represents those generations of rate payers whose main concern is not the disciplinary regime of the workhouse, or the desperation of its inmates, but the fact that he has to help pay for it. He gets a rough reception from the outspoken Annie Boarder (and also goes bankrupt later in the memoir after making over ambitious investments).

Nevertheless, the system swings into its accustomed routine and the old McBrides are removed to the workhouse. Greenwood gives an account of the ‘Salford Workhouse’ which expands those given nearly thirty years earlier in How the Other Man Lives:

The Salford Workhouse was a bleak barracks of a place whose row on row of un-curtained windows gave it a desolating and forbidding air. Within were flagged, echoing corridors whose walls were of glazed brown brick. Bare, scrubbed tables and benches furnished the common rooms. Fronting it, behind a high bare wall, was a wind-swept concrete yard divided down the middle by a run of spiked iron railings to segregate the sexes.

The women inmates wore a uniform of a blue frock reaching to the ankles, a grey shoulder shawl and a small hard bonnet held in place with elastic hooped round the bun of their hair. The men were shod in heavy boots, and wore suits of grey whipcord and black, broadbrimmed hats. When they walked abroad everybody knew their place of residence (p.22).

This reinforces with further detail the atmosphere of institutional meanness and also the function of the workhouse and its unfortunate inmates as highly visible public warnings to the poor to take every possible means to stay outside, however desperate their situation. As in ‘Joe Goes Home’, to set foot in the workhouse is to enter the portals of death:

My grandfather had prophesied that their committal to the workhouse was a death sentence. It was not long before [the two neighbours] Polly Myton and Annie Boarder were doing the rounds for the old couple’s wreaths (p.23).

8. The Greenwood Family Go Before the Board of Guardians from There Was a Time (1967)

As far as I can see, Greenwood’s last depiction of the workhouse is a directly autobiographical one about going in front of the Board of Guardians as a child (he must have been only ten years old and his sister was younger by several years). After his father’s early death (aged 43) in 1913, the Greenwood’s helpful and strong-minded neighbour, Annie Boarder (who is both like and very unlike Greenwood’s fictional creation, Mrs Bull) says they must draw on outdoor relief, though Mrs Greenwood feels too proud to do so:

‘Look, lass . . . get round to the Board o’ Guardians with the childer. They’ll have to give you out-relief’.

‘Nay, Annie. I couldn’t plead poverty. It’d stick in my craw’.

‘Don’t you talk so daft, woman. That’s just what they want you to do. How’re you going to manage rent, grub and clothes for three on what you earn?’ (p.68).

Despite Mrs Greenwood’s unwillingness, she knows that Annie Boarder’s economics are sound:

We went, Mother, Sister and I, to the Board. A row of wooden forms faced a table at which the three Guardians sat. There could not be any doubt as to what they were guarding. This was in a canvas bag on the table in front of them. There was an account book at its side.

The applicants were old men and women for the most part. They sat there dejected, motionless and silent except for wheezes and coughs . . .

Our turn came. My sister and I stood either side of Mother facing the Guardians. The canvas bag was open in front of the paymaster, coins spilling from its mouth. Mother answered the questions; the Guardians put their heads together and mumbled, then the paymaster, looking at the applicant said: ‘Very well. Half a crown’. He took a coin from the store and tossed it across the table. It bounced, revolved on its rim and stopped. The man reached for his pen to enter the item in his accounts.

Mother did a startling thing. She left the coin where it lay and electrified the room by announcing, in a ringing voice: ‘Half a crown? Half a crown for three for a week?’ I looked up at her alarmed. Her back was straight as a guardsman’s. She tossed her head defiantly. ‘I would not demean myself. I would sooner sing for our crusts in the gutter. Come along, children’. There was no comment from the Guardians nor a round of applause from the audience. As I turned to follow I saw the paymaster reach for the coin and slide it back into the hoard (pp.68-9).

I have given this scene almost complete because, like the whisky and cake at the Waverley passage above, the reader needs the rhythmic unfolding of its drama really to appreciate how skilful Greenwood’s writing is in this, his last published book (indeed I think it may be his best book, though not all agree with me – see Walter Greenwood’s Memoir: There Was a Time (1967). * and ‘Greenwood Come Home’ interview (Geoffrey Moorhouse, the Guardian, 1967) *).

First there is the setting of the scene as a public judgement – the applicants appear each in turn before their three judges. Then there is a sharp and quickly accomplished piece of wit which turns the meaning of ‘Guardians’ a degree – it is obvious what they are ‘guarding’, something absolutely literal and material: a bag of coins, rather than a more abstract principle such as fairness for either claimant or the rate-payer or both. Yet, while the Guardians guard the contents of the bag in one way, they are also careless of it, letting the coins spill ‘from its mouth’ in plain sight, showing that they do have resources in front of applicants to whom such wealth, so many coins, is beyond their imagination. Greenwood’s mother plays her part in answering the questions about their circumstances, and the Guardians collectively pronounce their judgement: ‘Half a Crown’. Half a crown in pre-decimal days was, of course, two shillings and sixpence and in 1912 would have been the equivalent of a little under £12 in 2024 – so the equivalent of four pounds each for rent, food and clothes – and impossible to survive on for long: remember this was a one-off payment not a weekly one (figures about value derived from the Bank of England Inflation Calculator: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator).

However, though the Guardians think they have done their duty and, without a thought for the mother and two children in front of them, immediately begin to move on to the next case, the coin seems to enact the way in which, as far as Mother is concerned, nothing is completed in this transaction. The fact that the coin has been ‘tossed’ at her rather then given to her shows the Guardians’ lack of respect and also leads to the coin stalling on its edge in a position between applicant and Guardians. The act and its seemingly meaningful consequence confirms Mother’s initial sense that to accept outdoor relief would be to demean herself. Nevertheless, despite her ‘startling’, extraordinary, and dramatic expression of dignity, individuality and independence, the Guardians do not react, except by scooping up the coin gladly and putting it back into – note the word – ‘the hoard’ – a depositary which is to be preserved for ever rather than circulated in use. Even sadder, ‘the audience’ for this piece of genuine theatre are too ‘abject’ to respond with applause – if Mrs Greenwood can make herself refuse half a crown, they cannot possibly afford such a gesture.

In fact, Mrs Greenwood must have been forced to make a subsequent application to the Board of Guardians for Greenwood gives an exact account of the slightly better outcome and then subsequent mean-minded bureaucracy in his essay ‘The Old School’ in his 1937 book The Cleft Stick:

The economics of this period should be of interest. I was nine years old when my father died, my sister four years my junior. My mother earned twelve shillings a week plus lunch and tea. we were relived to the extent of eight shillings a week as paupers by the Board of Guardians. This amount was reduced to half a crown when, as a child of twelve, I obtained spare-time work. So, you see the present Means Test is not an innovation (p.218).

9. Conclusions

‘The Greenwood Family Before the Board of Guardians’ completes the series of Walter Greenwood’s memories of the workhouse – and no wonder, for in his remembrance of the scene to which he was a ten-year old witness, he records and dramatises the inhuman face of the Guardians and the justified pride of his mother (who it should be said then worked herself nearly to death in several simultaneous waitressing jobs to keep the family together). This memory is closest to ‘The Inquisition’ in showing the operations of mean ‘Poor Law’ administrators and of pride and shame as factors deterring applicants for relief. His memories of workhouses cover experiences drawn from a longish period from 1913 to 1937, and were reconstructed in narratives between 1928 and 1967. The workhouse experiences described are by no means identical. ‘Mickmac’s Grandparents’ brings us back to the theme of Greenwood’s first workhouse narrative, ‘old Joe Goes Home’: that the workhouse presages death. The Love on the Dole material shows the unofficial ways in which, for good and ill, the late remnants of the workhouse system contributed to the economics of poverty during the Depression, and ‘Seventy Years in the Workhouse’ shows a lifetime of institutionalisation due to being born into poverty, together with some improvements in institutional social care and above all, the survival of individuality and spirit against all the odds -though of course our witness sadly, if necessarily, remains nameless. ‘The Inquisition’ and the Greenwood family appearances before the Board of Guardians shows in detail how the experience of the institutions of the Workhouse might operate and how they feel for claimants. The reference to the operations of the Means Test in the thirties shows Greenwood’s awareness of certain continuities across the ancient Workhouse system and the apparently more modern systems of unemployment benefit and those fragments of poor relief which were a very insubstantial safety net below. I think I am the first critic to identify the workhouse system as something which substantially engaged Greenwood’s attention, and I have taken the liberty of giving some of his workhouse narratives my own titles to identify workhouse material within larger works, and to suggest a genuine coherence across works written from his first days as a writer to his last published book, and in a number of the genres he worked in: short story, novel, documentary and memoir.

NOTES

Note 1. A quotation which exactly sums up what seems now the curious continued existence of the workhouse system into the nineteen-thirties (from M.A. Crowther, The Workhouse System 1834-1929 – the History of an English Institution, Batsford Academic, 1981, p.112). Crowther’s book is a wonderful standard work on the workhouse and as well as discussing the complexity of the system and how it changed over time, it is also a very good read, in my view. It is one of my main sources for knowledge about the workhouse and especially the changes introduced in the first three decades of the twentieth century (though in many cases these were only partially accomplished before the setting up of the post-war Welfare State, including the NHS). My other main source which is, of course, freely accessible online is the Wikipedia entry for ‘Workhouse’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workhouse). It seems a full and well-informed entry with links to the relevant legislation throughout the history of ‘Poor relief’, and I draw gratefully on it. I will later also draw on the knowledge and expertise in the very useful Workhouse site (see Note 13 below).

Note 2. The Workhouse System, p.87.

Note 3. The Wikipedia entry includes the information about the first use of the word ‘workhouse’ in this sense at Abingdon in 1603 (citing as its source material in The Workhouse – the Story of an Institution site, edited by Peter Higginbotham: https://www.workhouses.org.uk/intro/ . The OED entry details a longer, more various and more complex history of the word ‘workhouse’ itself, while also showing that this particular sense of the word (OED 2. b.) does indeed date to the early seventeenth century. In earlier uses (including some in Old English) a ‘workhouse’ was simply a workshop or place where things were made, though by the sixteenth century sense 2.b. was emerging from uses of the word to describe institutions such as ‘Bridewells’, where the criminal and the ‘idle’ could be imprisoned and made to do free labour for a parish in the associated workshop or workhouse.

Note 4. The Workhouse System: Note on Terminology number 4, unnumbered page before Introduction.

Note 5. The Workhouse System, p.87.

Note 6. The Workhouse System, p.89 – figures derived from Crowther’s table citing Parliamentary Papers 1928-9 (114), xvi, 746.

Note 7. There is a silent colour film of a knocker-up at work in Burnley in Lancashire sometime between 1946 and 1949, filmed by the very productive Burnley amateur filmmaker Sam Hanna (1903-1996) and posted on Vimeo by the North Western Film archive. See: https://vimeo.com/showcase/3066233/video/108109027 (and for an introduction to Sam Hanna’s work and legacy see: https://www.mmu.ac.uk/north-west-film-archive/projects/the-films-of-sam-hanna).

Note 8. The Workhouse System, pp.101-2.

Note 9. The Workhouse System, p.109.

Note 10. Thomas Noel has a fairly brief Wikipedia entry (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Noel_(poet)); he also has a DNB entry which adds some more detail, and notes that ‘The Pauper’s Ride’ is sometimes incorrectly attributed to the more famous poet, Thomas Hood (1799-1845), who did publish in 1843 the well-known poem about poverty titled ‘The Song of the Shirt’, a poem about female sweated labour, to which Greenwood refers in his second novel, His Worship the Mayor (1934). The composer Henry Russell has a Wikipedia entry (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Russell_(musician)), as does Sidney Homer (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Homer). The Petrucci Music Library site lists 1908 as the likely date of his Three Songs and hence of his ‘The Pauper’s Ride’ setting (https://imslp.org/wiki/Three_Songs,_Op.18_(Homer,_Sidney)).

Note 11. Here are the complete words of the poem, taken from the online version of Bartleby (2012 – a version of a classic anthology, The World’s Best Poetry, edited by Bliss Carmen and originally published by John D. Morris & Co, Philadelphia, 1904. See https://www.bartleby.com/lit-hub/the-worlds-best-poetry/the-paupers-drive. I note that the final refrain does allocate an ‘owner’ of the pauper and adds the hope of redemption to an otherwise very grim poem.

HERE’s a grim one-horse hearse in a jolly round trot, —

To the churchyard a pauper is going, I wot;

The road it is rough, and the hearse has no springs;

And hark to the dirge which the mad driver sings;

Rattle his bones over the stones!

He ’s only a pauper whom nobody owns!

O, where are the mourners? Alas! there are none,

He has left not a gap in the world, now he ’s gone, —

Not a tear in the eye of child, woman, or man;

To the grave with his carcass as fast as you can:

Rattle his bones over the stones!

He ’s only a pauper whom nobody owns!

What a jolting and creaking and splashing and din!

The whip, how it cracks! and the wheels, how they spin!

How the dirt, right and left, o’er the hedges is hurled!

The pauper at length makes a noise in the world!

Rattle his bones over the stones!

He ’s only a pauper whom nobody owns!

Poor pauper defunct! he has made some approach

To gentility, now that he’s stretched in a coach!

He’s taking a drive in his carriage at last!

But it will not be long, if he goes on so fast:

Rattle his bones over the stones!

He ’s only a pauper whom nobody owns!

You bumpkins! who stare at your brother conveyed,

Behold what respect to a cloddy is paid!

And be joyful to think, when by death you ’re laid low,

You ’ve a chance to the grave like a gemman to go!

Rattle his bones over the stones!

He ’s only a pauper whom nobody owns!

But a truce to this strain; for my soul it is sad,

To think that a heart in humanity clad

Should make, like the brute, such a desolate end,

And depart from the light without leaving a friend!

Bear soft his bones over the stones!

Though a pauper, he’s one whom his Maker yet owns!

Note 12. The recording is from a Victor 12 inch gramophone record (#35285-B, recorded February 14, 1913). The singer is Percy Hemus, baritone (died 1943), who gives a suitably dramatic performance of the song. Lucius1958 plays the record on their Youtube channel on a Columbia BL ‘Sterling’ Disc Gramophone dating to 1910. Given the dates of death of author, composer and performer I take it that this is indeed out of copyright in the UK, as Lucius1958 suggests.

Note 13. Information and knowledge about Salford workhouses provided by the invaluable The Workhouse genealogical site, edited by Peter Higginbotham (see https://workhouses.org.uk/Salford/ ).

Note 14. OED offers fifteen meanings of ‘grubber’, but not this one. It must be derived from sense 4.a ‘an eater, a feeder’, but has in this sense used by Greenwood been transferred from the person who feeds or eats to a building or institution which provides food or feeds – of course a key component of indoor relief, which does the essential thing of stopping the very poor from starving. Note how much emphasis our witness understandably puts on the food provided and its impact on quality of life.