This is a substantial political statement made to (or perhaps better for) a newspaper during 1941 by Greenwood and articulating his own understanding of the value and signifiance of Love on the Dole (novel, play and film). The statement, with a prominent headline and eye-catching typography, was published in two sister Sundays with broadly popular Labour sympathies. It probably therefore reached quite a large and sympathetic audience, especially since it was closely integrated with the film which was currently proving both a critical and cinema success. A box in the centre of the piece drew attention to the author and then handed over to the equally striking headline at the top of the article:

WALTER GREENWOOD wrote the book from which the film Love on the Dole was made. Now let the author tell you what the picture means to the New Britain.

And We Must Win the Peace

LOOKING past the war which is really nothing I more than a ripple on the surface of the sea of mankind’s history, I feel that we are on the threshold of a bright new world. On the threshold of a future which will please only honest men, the men who look to this war to produce a better and finer civilisation for the human race. But when we have won the war, we must see to it that we are not stupid enough to lose the peace, or the vision that we now have of the New Britain will be lost for ever.

For some people, of course, there will be defeat whatever happens to the conflict between Germany and ourselves. But the defeat will not be of Britain, as we want it to be, of Britain as we have always dreamed it ought to be. The losses will be borne by a Britain which must be defeated anyhow, by the Britain of the counterfeit cheapjack, the element which has lived on the success of the most prosperous Victorian generation. It is up to us to see that this war means complete defeat for the cheapjacks of Britain, to see that even when right triumphs, wrong, as represented by them, must be defeated. And we don’t really need the Nazis to help us to win this victory. We could have beaten this enemy long ago if we’d gone to war against him with the same spirit in which we now fight Hitler.

I wrote a book, you may remember. It was called Love on the Dole. Then it became a play. Now it’s become a film. In every guise, Love on the Dole was intended to point to the kind of Britain we don’t want after this war. A Britain of unemployment, misery, repression and injustice. This book was intended to be the harbinger of a New Britain.

Let us fight and beat Hitler by all means. But while we’re doing it, let us bear in mind these other enemies. For they are just as big a threat to democracy and decent living and to happiness as the Panzer Division of the German Army WE MUST BEAT THE ENEMIES AT HOME AS WELL AS ABROAD.

Let’s call out a home guard against the social evils which existed – they will exist again unless we stop them – at the time I wrote my book. Otherwise, we might as well lose that war to Germany.

At the moment we have a new morality. A new sense of social responsibility. ‘Never again must we have the evils of unemployment, of undernutrition, of social injustice’, says the nation.

Fine, I’m glad to hear it. But it’s a great pity it takes a war to make us say it. A still greater pity if we forget these high ideals when the war is won, and slip back, gradually though surely, into the old evils.

It has always been deplorable to me that it takes the catastrophe of war to awaken us all to the possibility of a new morality.

Still, if war is the only medicine, let us act like men and welcome it.

HUMANITY is a stuff that does endure. And never before, in the scarlet and gold procession of the history of these islands, has the national character risen to such an emergency nor shown such great endurance.

For what?

Now that the forgotten men and women of Love on the Dole have been remembered; now that, with all the other members of the community, they have magnificently answered all and every call that has been made upon them, what is it that burns in their hearts?

These men and women have stood up to the savagery of the bomber; these men and women have rallied to the ambulances and the fire services: these elderly people forsake their beds to take turns to patrol, steel-hatted, the midnight streets – all these men and women have aroused the sober respect and enthusiasm of the world.

Men and women are resolved that the dead days of yesterday are well and truly dead, that never again are the money-lending financers to rule the roost; but that humanity is to come first and personal greed nowhere at all.

The ten-per-centers, the crooks and the wise guys will not like it. Our New Britain must not take account of them, except to put them where they belong – in the clink.

Britain, with all its unique reservoir of skilled labour and its inventive genius, all encompassed with a tiny green isle intersected with wonderful communications, can and shall take the van and lead the world again as it did in the brave days when British craftsmen and women were supreme (The Sunday Pictorial and the Sunday Mirror, 17 August 1941, p.7 in both cases).

In my book on Greenwood in 2018 I quoted just the paragraph from this Sunday Mirror article opening ‘ I wrote a book, you may remember’ and I realised then it was a very significant paragraph showing the author’s developing view of the relationship between his work, the new film and strongly emerging ideas about the war as ‘a People’s War’ for a ‘New Britain’. However, I now see that actually quoting the whole article greatly expands our understanding of how Greenwood saw the People’s War, and what is more the article has never been referred to at all in any Greenwood scholarship beyond my own too brief citation (1). So, I have put in the whole piece here in order to follow Greenwood’s thoughts in the early forties. I do not think it is one of his best pieces of prose. Indeed, it is unusually clumsy and rhetorical compared to his usual standards, but that may be partly because of the kind of explicit style the Sunday Mirror and Sunday Pictorial preferred for their political articles, and also because it maybe had to be delivered at speed as a journalistic commission (though Greenwood wrote stylistically better pieces under those kinds of conditions). Nevertheless, it is a unique explanation of Greenwood’s People’s War thinking and hence of his sense of the value of Love on the Dole and is well worth a careful commentary given the lack of notice it has received.

First of all the introduction of Greenwood in the central text-box makes a quite grand claim for the new film of Love on the Dole – that it is a ‘picture’ at the centre of public understanding of an emerging new conception of the British State post-war – a ‘New Britain’ in fact. While it has often been agreed that the novel and play of Greenwood (and Gow’s) work tend to avoid blame and partly therefore keep the maximum number of people on side with its distressed but innocent working-people, this is not quite the case with the author’s commentary on the film here. On the contrary, it identifies some specific enemies within who must be fought in conjunction with the external enemy constituted by Nazi Germany.

First the enemies of the ‘New Britain’ are identified in abstract terms as ‘social evils’, and this seems to be a reference to the ongoing work of Beveridge’s Commission and its goals (though its Report was not published till 1942). Greenwood gives a quotation the source of which I have not located: ‘Never again must we have the evils of unemployment, of undernutrition, of social injustice’ (these exact words do not occur in this form in the final Beveridge Report , a full text of which is available on the Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.275849): Beveridge’s goals were (and were usually quoted as) the abolition of the five social evils of ‘Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness’ rather than these three-term goals Greenwood identifies (Beveridge Report, ‘Three Guiding Principles for Recommendations’, paragraph 8). It may be that Greenwood is quoting an early press report of Beveridge’s work (for an account of Greenwood’s responses to Beveridge mainly in his creative work see Walter Greenwood and the Beveridge Report (1941-1945) * ). There certainly was shared ground between that of the Beveridge Report when it appeared and this early reference by Greenwood, as suggested by this panel from the rear of the 1942 Daily Herald Full Guide to the BEVERIDGE REPORT on the SOCIAL SERVICES. Like the film of Love on the Dole it links pre-war poverty and its solution with post-war poverty and its solution:

Then enemies of the New Britain are seen less abstractly as particular social types. These are somewhat variously labelled as those who are not among the ‘honest men [sic], who want to improve civilisation for all’, and those who are ‘counterfeit cheap-jacks, the element which has lived on the success of the most prosperous Victorian generation’. Presumably, these cheap-jacks are not just those who exploit their peers by selling inferior goods at inflated prices in local markets, but also more elite groups who carry out similar business at a national scale, and who fail to distribute the (potential) benefits of the industrial revolution fairly between owners and workers. I note that the very relevant question of empire in the British economy then is not raised, though towards the end of the article Greenwood wants to see British ‘skilled labour’ leading the world as it did in the past, though still without any comment on any imperial or emerging future post-imperial context. Further on, those of ill-will are referred to as ‘the ten-per-centers, the crooks and the wise guys’. Initially, these are seen simply as those who ‘will not like’ the New Britain, but by the end of the sentence they are all three identified as categories of people who should be in jail. The crooks and wise guys are presumably wartime spivs, inheritors at whatever scale of the ‘cheapjack’ tradition which comes down from the [unequally distributed?] successes of Victorian Britain, but who are the ‘ten-per-centers’?

‘Ten-per-centers’ is an uncommon phrase for which OED gives only one really relevant sense: ‘an investor receiving ten per cent interest’. OED also identifies few usages, linking its definition only to a usage from 1902 in the Westminster Gazette (30 July 9/2): ‘Anxious as he is to make every speculative investor in the mines a ten-per-center’. OED gives the phrase a second meaning as referring in the US to a theatrical agent, who will take 10% commission from an author (given the contents of Greenwood’s 1936 novel Standing Room Only, this might seem quite relevant, but I suspect is not!). Searching the British Newspaper Archive suggests to me that ‘ten-per-center’ was not a phrase that was commonly used during the thirties and forties. It is quite surprising to find Greenwood using a phrase in the first half of the twentieth century the meaning of which is now unclear, but such seems to be the case. In the light of his subsequent demand in the article that ‘the money-lending financers shall never again rule the roost’, it seems reasonable to assume that his ‘ten-per-centers’ are in one way or another speculative investors living on unearned income. Greenwood thinks these are comparable to smaller-time crooks and cheap-jacks, just as in the novel of Love on the Dole, he describes the ‘low finance’ operations of Mrs Nattle as ‘conducted on very orthodox lines; to be precise, none other than those of the Bank of England’s or of any other large money-lending concerns’ (p. 103).

Greenwood makes it very clear that he sees total wartime engagement as needing to remain mobilised into the peace with the related aims of defending and expanding real democracy: ‘Let’s call out a home guard against the social evils which existed’. He even quotes with adaptations of his own the rolling caption by A.V. Alexander at the conclusion of his and Baxter’s film. Here is the original caption:

Our working men and women have responded magnificently to any and every call made upon them. Their reward must be a new Britain. Peace will come. Never again must the unemployed become the forgotten men of the peace.

A.V. Alexander, First Lord of the Admiralty.

Here is Greenwood’s adaptation for his manifesto, with a shift in tense:

Now that the forgotten men and women of Love on the Dole have been remembered; now that, with all the other members of the community, they have magnificently answered all and every call that has been made upon them, what is it that burns in their hearts? (2)

Of course, the answer is the hunger for a new and more equal Britain in which unemployment and poverty and inequality are banished into a terrible past. The article is a significant public statement by its author of his perception of the value of the tri-partite text of his Love on the Dole, and it is a value which is primarily social, historical and political with a real world national impact. It is noticeable that this article asserts the unity of all three texts of Love on the Dole, as if there has been no change in its meaning between 1933 and 1941, but it is clear that for Greenwood the meaning of the novel and play has been greatly expanded by the film adaptation and its new wartime context, and perhaps by his work with the director John Baxter in particular. There is thus a retrospective aspect to Greenwood’s assertion here of the unified purpose of Love on the Dole, but it makes a great deal of sense from the perspective of 1941 (given a large addition of optimism about the victorious outcome of the war, and about post-war political developments). This Sunday Mirror / Sunday Pictorial is a significant statement of Greenwood’s political beliefs and post-war hopes for Britain: the 1941 film of Love on the Dole was not only the realisation of a project long desired by the author, but also a catalyst in developing his own political thinking along a People’s War trajectory.

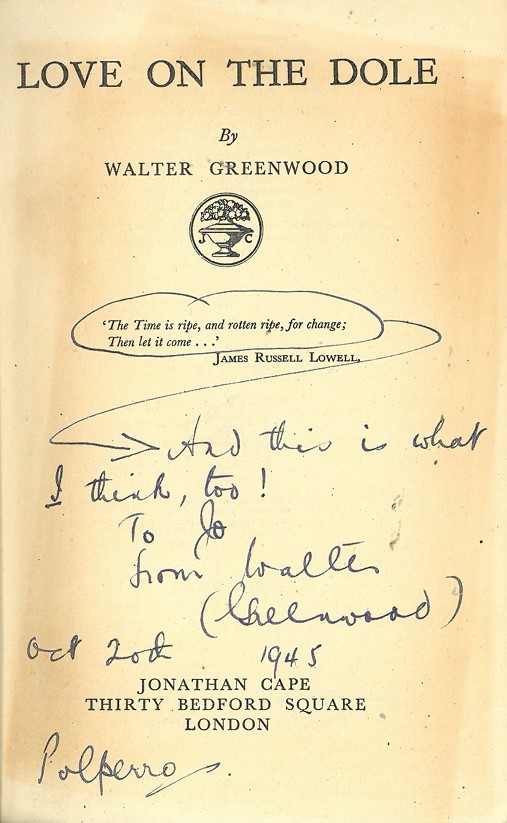

A signed and inscribed copy of a new 1945 reissued edition of the novel of Love on the Dole suggests that Greenwood continued to cherish these ideas throughout the long years of war and that they were very much uppermost in his mind as the war concluded and people could turn their minds towards making a new kind of peace:

(Note that this article is also incorporated into a longer article with a somewhat different project and argument: The Value of Love on the Dole – the Short View and the Long View (1933-1980)).