There are two (or three) songs included in the published play-texts by Samuel French and Jonathan Cape for Love on the Dole (1934, and 1935 respectively), one towards the beginning of the play, the other(s) towards the end. There are also two hymns (or perhaps the same hymn twice), but only in the Cape edition, and in both editions at the very end of the play comes a quite unexpected bridal march. The Samuel French edition replaces the second hymn with a song – hence my equivocation about whether the play contains two or three songs. Before that we hear a Socialist anthem being sung offstage by the marchers protesting against the Means Test – though two different anthems in the two editions. No one has paid these pieces of music any attention, but I think they contributed valuably to characterisation and drama in the performances of the play. Here I do my best to reconstruct the songs and their impact on the play – the first time I think that anyone has looked in any way at these musical elements in the drama since the early performances in the nineteen-thirties.

The first song is in Act I and is sung by Mrs Dorbell just before the séance begins (Cape p.44, French p. 27) and the words of its first line are ‘We’ll laugh an’ we’ll sing an’ we’ll drive away care’. That opening line and the remaining lyrics strongly suggest that it is a folk-song. The song is in fact also in the text of the novel with nearly identical words, but its context is very different – and is a deeply unromantic and cynical one:

A back entry for a love bower! A three-foot wide passage, house backs and backyard walls crowding either side; stagnating puddles in the broken flagging; the sounds of the traffic of people’s visiting the stinking privies, and, hark, over the roof-tops, the sound of a cracked voice singing shrilly. Mrs Dorbell’s, the old hag, who, when drunk, always chose the privy seat on which to sing the same song:

‘We’ll laugh and sing an’ we’ll drive away care;

Ah’ve enough for meself an’ a likkle bit t’ spare.

If a nice yeng man should ride my way

Oooow, Ah’ll make him as welcome as the flowers in May!’

He could imagine the expression of glassy-eyed vacuity on Mrs Dorbell’s face. His arm, round Sal’s waist, relaxed. He could feel the dulling sense of utter hopelessness creeping over him. (p.149)

Larry and Sally are trying to find somewhere private to kiss and say goodnight, but can only find the alley at the back of the Hardcastle house, where this sound-environment entirely ruins the moment, and makes Larry, at least, feel hopeless that anything good could ever thrive in Hanky Park. A viewer of the play who had read the novel might remember this song context, but on the whole it seems unlikely. What novel and play share in respect of the song is that Mrs Dorbell sings it when she has had a few, and perhaps despite the harsh ‘hag’ description in the novel, it is also a sad commentary on her own lost youth, and that of all the older women in Hanky Park, but makes clear her surviving openness to any passing entertainment or imagination thereof.

The nearest folk-song lyrics I have been able to find to these words are from a song known as ‘Drive Away Dull Care’, but the lyrics of the two are very different, as are their themes. In addition, ‘Drive away Dull Care’ was anyway only known from one singer in St Edward Island, Newfoundland, before being more widely popularised by live performances and recordings from the nineteen fifties onwards. Here is ‘Drive Dull Care Away’ sung by the singer and scholar Joe Hickerson, together with a chorus, on his album ‘Drive Dull Care Away, Volume 1’ (Folk-Legacy Records, 1976). It was Hickerson who made the song more widely known: https://youtu.be/CcgOorCbW4k (3 minutes 27 seconds).

While the Edward Island song is about making the best of life by driving away care and instead sharing jollity with friends, Mrs Dorbell’s song is notably and appropriately about ignoring serious issues and taking whatever opportunity for strictly individual pleasure comes your way. Discussions of the St Edward Island ‘Drive Away Dull Care’ often gesture towards a comparable English broadside ballad, but no-one seems to have found it, and nor have I, so far! (1) Perhaps the Love on the Dole song derives from this ballad, though I suppose it is equally possible that Greenwood made up these folk-song like lyrics, and indeed that one of the actors who played Mrs Dorbell might have been expected to improvise a suitably folk-like tune in the play (it is only one verse, after all). On the whole I think it does look like a reasonably convincing folk-song verse, whether ‘authentic’ or not (though I am less convinced by the second line). Here it is in its dramatic context in the Cape edition:

Mrs Dorbel is not invited to sing by the assembled company, but bursts out spontaneously, and I take it loudly, into this song, presumably in anticipation of the free entertainment to be provided by the séance, and also because she is already stimulated by several (large) nips of gin. Mrs Bull is also appreciative, and makes her only comment anywhere in the play (or novel) on the restorative power of music. Mrs Dorbell would like more music, and asks Mrs Jike to show her skills on the concertina (the novel makes only the one comment on this: ‘she was an inexpert performer upon the concertina’, p.37, though elsewhere it refers to her playing the accordion too – see below). Clearly, though, Mrs Jike feels that the wrong tone and atmosphere is being set for a successful séance by Mrs Dorbell’s song (and perhaps also feels she should be the centre of interest). Her comment ‘not that sort o’ music’ implies that this song is inappropriate, and perhaps she is especially disapproving of the song’s openness to sexual opportunity (particularly on Mrs Dorbell’s part?) should (any) ‘nice young man’ ride by. A hymn would much better set a respectful and reverent atmosphere in which to invite the presence of the spirits of the departed. No hymn is named – but one is in the novel in connection with the Spiritualist Mission attended by Mrs Jike and her peer Mrs Scodger:

Presently, from the Scodger abode, came the concerted cacophony of accordion and trombone. As an accordionist Mrs Jike was as ungifted a performer as Mrs Scodger was upon the trombone, nevertheless, between them, they managed to provide musical accompaniment to the hymn singing at the spiritualists’ mission situated over the coal yard at the far end of the street.

The noise of the music attracted the children: congregating round the door and under the window, some, more curious than the rest, muscled themselves on to the sill to peer through and to feed their gazes on the strange spectacle of the two musicians, tiny Mrs Jike stretching and pressing her instrument, buxom Mrs Scodger, puffing, pushing and pulling on the brass, between them managing to arouse the suspicion in a chance auditor that the tune they were playing was ‘Whiter than the Snow’, a hymn of which the mission was inordinately fond (pp.58-9).

The novel does not encourage admiration of the musicianship of Mrs Scodger or Mrs Jike, and the play carries that over to Mrs Jike at least, though in ways that make good dramatic sense in the scenes where the two songs feature. The hymn is correctly known as ‘Whiter Than Snow’, and dates from 1872 (words by James Nicholson, melody by William Gustav Fischer, both of whom contributed to Evangelical Revivalism in the US). (2) It seems likely that this might have been the hymn performed before the séance in the play by Mrs Bull, Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Jike. I am not sure whether Greenwood forgot in the novel that he had earlier said that Mrs Jike played the concertina (p.37) rather than the accordion (p.58) or whether she is an equally uncertain performer on both instruments. They are related in that both are free-reed instruments (where air is passed through a series of fixed-pitch vibrating reeds each in a small frame, usually made in modern instruments from brass) and were mass-produced from the nineteenth century onwards, and often available second-hand therefore for less well-off musicians, but they look rather different, sound rather different, and are played in somewhat different ways. There have been many types of concertina and accordion, but the images below show the main differences in appearance – the first is a concertina, the second a button accordion, the third a piano accordion and the final image shows a splendid collection of concertinas and accordions (all images are free to share and are provided by the Wikipedia entries on concertinas and accordions – for full details see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concertina and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accordion ).

Below is the best I can currently do to guess at what the Love on the Dole folk-song might have been like. I have found it impossible to fit the almost completely different lyrics of this song to the St Edward Island ‘Drive Dull Care Away’ tune, so have improvised a possible tune to go with these lyrics. It ends up as a rather generic ‘folk song’ but is perhaps better than nothing in the absence of any known recordings or clear identification of these lyrics or a tune for them (sung and recorded by the author on 26 January 2024 – if I find something better I’ll willingly replace this . . .).

And here is a version of ‘Whiter Than Snow’ from the A Capella Hymn Youtube site, which helpfully has words, ‘shape note’ notation, accompaniment and a capella singing, and is, I take it, intended for sharing: https://youtu.be/ORslb2Tw3ws (2 minutes). I think this is a rather fine hymn, but like ‘We’ll Laugh an’ Sing an’ Drive Away Care’ (and as we shall see in fact like the final song and music in this play), this is surely deeply ironic in a performance by this ‘Chorus’ – because they are not perhaps evidently or sincerely seeking redemption or being ‘washed whiter than snow’ at this particular point – they want to ask the spirits about the Irish Sweepstake and to tell Jack Tuttle that his posthumous half-crown is in safe hands (those of Mrs Bull, in fact). The recording is of the whole hymn, but it seems more likely the actors might have sung perhaps just two verses plus the chorus twice. This still below from the 1941 film shows from left to right: Sally, Mrs Hardcastle, Mrs Jike, an unnamed neighbour, Mrs Bull and Mrs Dorbell. The particular moment just before the séance caught in the still perhaps makes the scene look more comfortable and convivial than it might do.

While both the Cape and French editions of Love on the Dole include the song, there are some differences in the dramatic context it is given – while Mrs Dorbell finishes one verse at least in the Cape, she is interrupted before she can finish in the French edition, and there Mrs Bull’s enjoyment of the song is replaced by disapproval through both gesture and sarcastic comment (‘freezing the singer with a look’; ‘Well, that’s better out than in’) – and presumably replaces in another voice Mrs Jike’s disapproval of sexual suggestion in the song. There are also differences in the stage directions, and the hymn singing is not there at all, nor Mrs Jike’s concertina accompaniment:

The Samuel French edition is based on the earlier performances at the Manchester Repertory Theatre in 1934, while the Cape edition is based on the later 1935 performances at Garrick Theatre London. (3) At some point the co-authors presumably decided that the severer response was not quite appropriate to Mrs Bull, and replaced it with a more carnivalesque reaction – which I think does seem more in tune with her general character and her (sceptical) enjoyment of the séance. I think the hymn in the Cape edition builds up nicely to the séance and shows us the rather peculiar ‘spiritual’ entertainment in which the three older women participate. However, maybe earlier it was felt more important to get on with the séance scene which has a number of key roles: to show the older women’s enjoyment of free and self-created entertainment, to show their exploitation of any situation which might lead to further possibly useful local knowledge or profit, and to give comic opportunities deriving from the then currently quite influential practices of spiritualists. These elements combined, together with the ironic use of the hymn, may tell us something about Greenwood’s scepticism towards religion more generally, and in this scene in novel, play and film there is an implication that religion of any sort is a tool of capitalist manipulation and distraction from the real issues (as it is for Mrs Jike and Mrs Dorbell’s little enterprises – see also Love on the Dole and the Clergy).

The Socialist anthems come into the play in Act III, Scene 1 – offstage. We hear them from inside the Hardcastle house, as Larry tells Sally he must go and join the march, partly as a labour leader and partly in that capacity to head off a direct clash with the police. In the Cape edition we get this stage direction:

(She holds tightly to him. A big drum starts down the street, and voices sing ‘The Red Flag’. Larry starts up) (Cape edition p.102).

In the Samuel French edition we get an identical stage direction except that ‘The Internationale’ replaces ‘The Red Flag’ (p.57). Both songs were Socialist anthems widely known across Europe and beyond, and always intended to be internationalist in mood and scope. Both stem from Socialist movements in the late nineteenth century; ‘The Internationale’ was written first, in 1871, though not sung to the tune with which it is now linked till 1888. The words were by Eugene Pottier, a member of the Paris Commune, while the tune was added by Pierre de Geyter (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Internationale). ‘The Red Flag’ was written by the Irish Socialist Jim Connell, though he did not intend it to be sung to the ‘O Tannebaum’ tune as it usually now is (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Red_Flag). Here is a one-minute extract from ‘the Internationale’ in what seems an appropriate 1926 British recording released on a fascinating Lansbury Labour Weekly 78 (as usual click back to thi site when the clip repeats on a loop). The singer is John Rufus, also known as John Goss: https://youtube.com/clip/Ugkx2SD95BI5_yDKEO5CjKucSsjVaTsjLZL1?si=EOCBLSoeOcnzA-Xd (from the EMG Colonel Gramaphone collecting Youtube site: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VoSPAbUsZac ). On the same site and again sung by John Rufus on a 1926 Lansbury Labour Weekly 78 is ‘The Red Flag’. Again this is a one-minute extract: https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxXK6HnXCPtk57mm2nWmQXTusYzPZqktf9?si=-dqVYwjyaZkaaCsN ; (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7JYAb1veZs). Remarkably, George Lansbury’s Wikipedia entry includes a link to a speech by him (I think originally on a 78 itself) which introduces this set of 78 records published by his Socialist paper, the Labour Weekly: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:George_Lansbury_Speech_from_Lansbury%27s_Labour_Weekly.ogg (3 mins 3 seconds).

Both songs were very well-known, and indeed ‘The Red Flag’ had been the anthem of the British Labour Party since its foundation (under that name) in 1906. I am unsure why the two editions specified the different anthems. Many reviews of the play in 1935 praised it precisely for not being propaganda or explicitly ‘political’ (though this is in many ways an odd line of argument), but these clearly were political songs. However, they are sung off-stage and the audience probably only got a line or two (as in my musical illustrations), and since they are associated with the marchers whom Larry is trying to ‘moderate’ and protect from the ‘extremism’ of ‘agitators’, might even reinforce the play’s moderation for audience-members who might otherwise not find these anthems to their taste (which is not to say that other audience-members might not enjoy getting even a snatch of Socialist song on to -or nearly on to – the British stage).

The second (‘secular’ rather than political) song of the play comes right at the beginning of Act III, Scene 2 (French p.63, Cape p.113), and has no precedent in the novel. It again involves the three older woman, often referred to in reviews but never in the play itself, as the ‘chorus’, and also again follows a certain number of nips of gin by all three. Unlike the case of the first song in the play, there is no doubt about the lyrics, tune or composer of the second song. It is ‘The More We Are Together’, ‘Written & Composed’ (though ‘founded on an old air’) by Irving King in 1926. This was something of a hit in the mid-twenties, particularly as sung by (an apparently) Irish singer called Talbot O’Farrell (he had re-invented himself as an Irish singer in 1912, though born in Hull, and having performed in a Scottish persona as Jock or Will McIvor since 1902). Here is the cover of the sheet music (with accompaniment for piano or ukulele) published by the Irving King Music Co. and crediting O’Farrell’s success with the song:

The song as printed in the sheet music has an introductory section sung to a foxtrot rhythm which recommends the chorus which follows as the best way to end any convivial party and all go home in good humour. In fact (though coincidentally) the chorus echoes the sentiments of ‘Drive Away Dull Care’ in recommending friendship as the best way of enjoying life. Assuming that the song in the play would need to be relatively brief and because the words are especially (if ironically) appropriate, I think the play’s Chorus would have just sung the refrain, which oddly in this song is the main musical event and heart of it. That chorus therefore is what I have sung below.

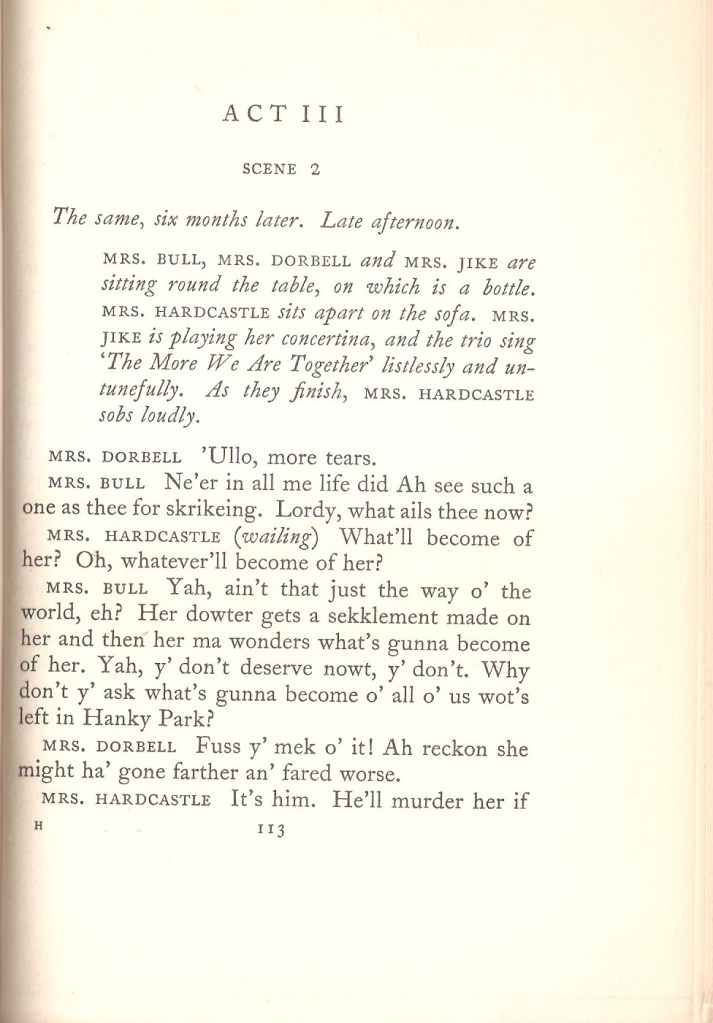

Here is the dramatic context of the song in the Cape play-text (it is pretty much identical in the French edition, though in general the two editions take a different approach to the representation of Salford dialect):

The stage direction (‘the trio sing “The More We Are Together” listlessly and untunefully’) makes clear the ironic use of this explicitly cheering and convivial song. Despite the concertina accompaniment and the ensemble singing of the three women they are not exactly in accord – neither with each other because they are always in competition, nor with the mood in the Hardcastle household at this point in the play, when Mrs Hardcastle weeps at the thought of Sally becoming Sam Gundy’s ‘housekeeper’ in his house in Wales, and very alarmingly fears that Mr Hardcastle may murder Sally when he hears. The three women try to persuade Mrs Hardcastle (each in their own style) that this is a good outcome for her daughter: Mrs Dorbell takes her usual view that acquiring some money is always good, however earned, Mrs Jike enjoys her gin and cannot see why Mrs Hardcastle won’t take a nip too, and Mrs Bull gives her more thoughtful (if hard to take) view that getting away from Hanky Park after Larry’s death will do Sally good and no harm, and that if she stayed she might become suicidal. In the context, Irving King’s very jolly and life-affirming song seems brilliantly unsuitable, but presumably instantly regained audience attention after the scene break, and created an immediate sense of tragi-comic discord and irony.

There are two further pieces of music in the play, also in Act III Scene 2, and both accompanied on concertina. One is played onstage by Mrs Jike to accompany Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Bull, and is again a hymn. We probably only get the first line because Mr Hardcastle asks the trio to leave the house immediately. They are present because they have been trying to persuade Mrs Hardcastle that Sally becoming Sam Grundy’s mistress is a good thing overall. They have also been adding generous measures of gin to their cups of tea and becoming merrier and merrier despite Mrs Hardcastle’s obvious misery and her fears about what Mr Hardcastle will do when he hears the news. Here are the relevant lines and stage direction:

MRS JIKE (who has been drinking diligently). Come on gels! Let’s be happy while we can. Y’re a long time dead.

(She seizes her concertina and launches them into a hymn. The door opens and Hardcastle appears. The music stops. He glares at the three women, They rise uncomfortably).

HARDCASTLE. Get out o’here! (p.118)

The hymn is not named. I think it might be perfectly appropriate if it were a reprise of ‘Whiter Than Snow’, which again would have the ironic relevance of being sung to celebrate while the three are drinking and encouraging the exchange of sex outside marriage for material reward, and the predatory behaviour of Sam Grundy.

The Samuel French edition also specifies a song at this point, but not a hymn, and omits the concertina accompaniment (again presumably because the Manchester Repertory cast had no concertina player to hand). Here is this version of the lines and the stage direction:

MRS JIKE (who has been drinking diligently, fills the three cups). Come on gels! Let’s be happy while we can. You’re a long time dead

(They begin to sing, off key, ‘For you’re here and I’m here, so what do we care etc’. The R. door opens and HARDCASTLE appears. The music stops. He glares at the three women. They rise uncomfortably. Mrs Hardcastle also rises).

HARDCASTLE. Get out of here! (p.66).

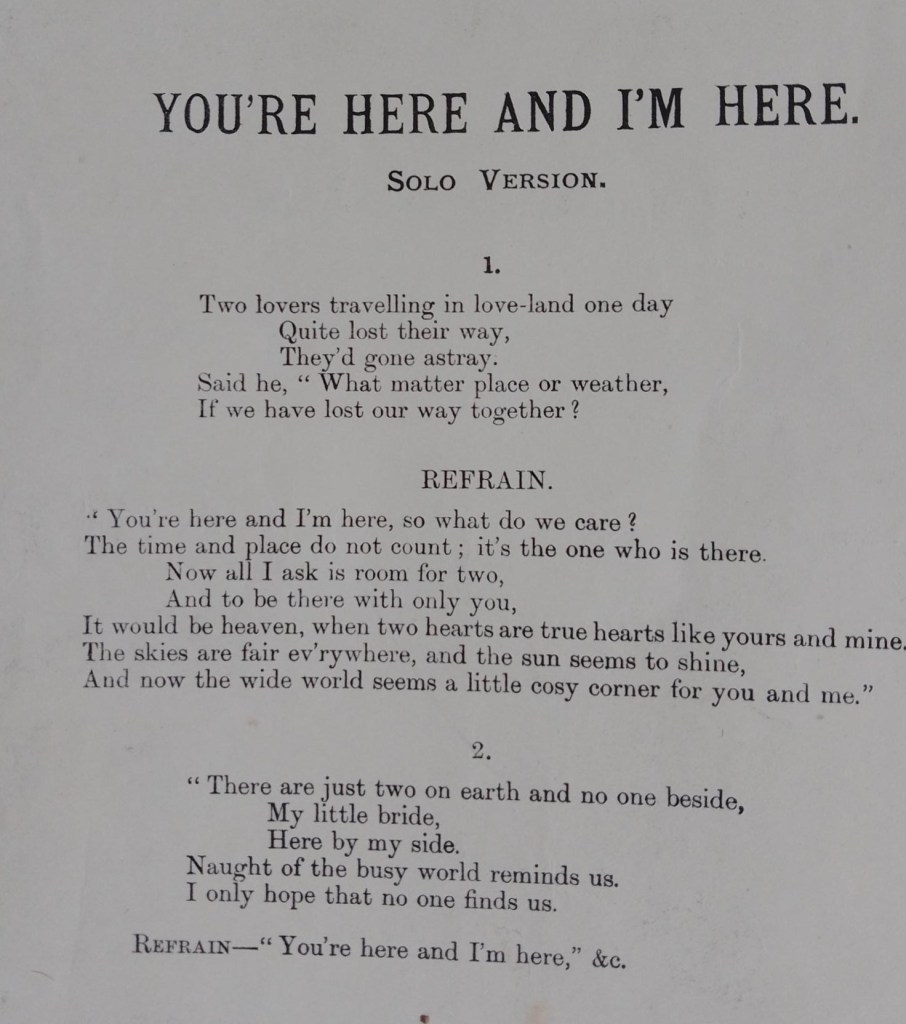

The lyrics given are the refrain to a Broadway musical hit of 1914, properly titled ‘You’re Here and I’m Here’, with words and music by the very successful American songwriters Harry B. Smith (1860-1936) and Jerome D. Kern (1885-1945). It originally formed part of the musical The Laughing Husband, though in Britain also appeared in a revue called The Passing Show. (4) There were sheet-music editions of the song, and, as so often, YouTube gives us a version of the song, though this time not from a 78 recording from the time but a more recent though very much in period-style performance:

Posted on YouTube (28 December 2020) by Sheet Music Singer; vocal and video of the sheet music by Fred Field. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9mq6VhrJ51k&t=118s . Though I imagine in the play we would only get at most one sing-through of the refrain, the inappropriateness of the words and jaunty music about true love to Sally’s actual situation would be immediately clear to any audience members familiar with the song and its context: yet another ironic use of music and song in the play. The lyrics of the refrain superficially resemble those of the earlier Love on the Dole folk-song (‘We’ll laugh and we’ll sing and we’ll drive away care’), but are about nothing mattering if two people are in love, rather than as in the Chorus’s more cynical implication that nothing matters if you have a drink (or three) and can escape for a while.

The final tune of Love on the Dole is played off-stage on the concertina as Sally makes her final exit to the taxi which will take her away from Hanky Park and to Sam Grundy’s house in Wales, essentially of course against her will and yet ‘consented’ to in order to save her family from absolute pauperdom. Here is the preceding and following line of dialogue and the substantial stage direction from the Cape edition:

Mrs DORBELL. Hey! Here’s a taxi come f’your Sally.

(There is an excited talkative crowd in the darkness outside. Sally stands for a moment, hoping that her father will turn his head. The concertina outside strikes up ‘Here Comes the Bride’. Sally bites her lip, and then, drawing herself up proudly, marches out to the taxi. Laughter and jeering are heard. The taxi drives away and the noise dies down. Mrs Hardcastle comes over to her husband).

MRS HARDCASTLE. Don’t tek on so, Henry. Y’ve got a job now. That’s summat to be thankful for (p.125).

As with other uses of music in the play this snatch of tune is instantly recognisable as deeply ironic since marriage is far from what Sam Grundy is offering in his ‘contract’ and far from what Sally wants now that Larry is dead. The shaky performance on the (inappropriate?) concertina is bound to sound comic or I think in the context strikingly tragi-comic.

The Samuel French edition has almost exactly the same stage direction except that the concertina is replaced by singing: ‘Laughter and jeering are heard, then the discordant singing of ‘Here Comes the Bride’ (p.69). We know that in the Garrick production Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jike could play the concertina because this is specified in the opening stage direction of Act II, discussed earlier. It may be that this alteration is simply because the Manchester production had no concertina player available in the cast. Sadly, I can find neither a concertina snatch of the first line of ‘Here Comes the Bride’ nor a suitably shaky performance in character, but I hope this more expert player of the tune on the at least related accordion will give some impression of the effect in the play – the reader will have to imagine it less well played: https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxgP_actXWXDSXO2GHXOvs8d_HC3crWr-k?si=JYdL1-tLbdYmcnow (5).

It is notable, though, that the film did not find any of these two songs necessary, nor the hymns nor the bridal march nor in any scene the concertina, and nor I think did the BBC radio adaptations. Nevertheless, they were part of the original Manchester and Garrick performances which ran into their hundreds, and which according to Greenwood were seen by some three million people by 1940 (in his letter to the Manchester Guardian, 26 February 1940). I have found only one review of the play of Love on the Dole which makes any reference to music being included in the performance, and that is to a piano accompaniment in an amateur production by the Talbot Thespian players: ‘Effective musical accompaniment was arranged by Mr. Gwilym H. Thomas. A.R.C.M., M.R.S.T. and Madame Ethel Thomas as pianist’ (Neath Guardian, 22 April 1938, p.2). The relation of this to the printed stage directions is not spelled out – ‘arranged’ might or might not imply that existing music was adapted for piano or paiano accompaniment. However, I think both songs, and the hymn and the bit of bridal march, have a clear dramatic value in their scenes, especially as no doubt uniquely performed in a melancholy/hilarious/ironic style by Mrs Dorbell, Mrs Jike and Mrs Bull. I hope that this reconstruction of the songs and music and their potential effects might be taken into account by anyone reading or studying the play, and would very much encourage their exploration in performance by anyone working on a contemporary production of the play of Love on the Dole.

A Brief Coda on the Film

I say just above that the film did not find either of these songs (nor the hymn) necessary. That is true in that it features neither the apparent folk-song ‘We’ll Drive Away Care’ nor the popular song ‘The More we Are Together’. However, if you watch and listen carefully to the film (at 50 minutes 20 seconds in) you will find that Mrs Dorbell singing on the privy is rather discretely retained, though she sings the first line of a somewhat different song, and it is not Mrs Dorbel singing, but another of the older female inhabitants of Hanky Park! The different song and singer, though, do have a similar dramatic impact in the film to that of the moment in the play. In the film, we see both the young couples (separately) trying to find somewhere quiet to say good-night in the rear alleys of North Street, where the Hardcastles and Helen’s parents live. Sally is worried because she has heard that Ned Narkey threatened Larry with violence at Marlowe’s works if he does not stop going out with her. Larry says to ignore Narkey. As the couple walk along a dark, lamp-lit alley (in the splendid and large-scale set where exterior scenes were filmed), we hear the film’s version of the soundscape of Hanky Park at night: first a snatch of song by an off-stage voice, then also off-stage, Helen’s drunken parents arguing, as usual. The song this time is one often called after the line at the beginning of its refrain, ‘Just a Song at Twilight’. Strictly, the song’s title is ‘Love’s Old Sweet Song’. The lyrics were written by Graham Clifton Bingham, who then sought a composer to write the music – several offered melodies, but Bingham chose that offered by James Lynam Molloy (1837-1909 – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Love%27s_Old_Sweet_Song). The song was published in 1884, so was considerably older than ‘The More We are Together’, but became a hit quickly and retained its popularity well into the twentieth-century, so it will have been immediately recognised by Love on the Dole cinema audiences. I think it is indeed a fine tune, though over time its sentimentality was often subject to parody. Here is the whole song performed by the great (and genuinely) Irish tenor John McCormack (1884-1945), and recorded for Victor Records in 1927 (helpfully posted on YouTube by Tom Smith; there is no reference to its source but DAHR – the Database of American Historical Recordings – gives the gramophone record reference as Victor CVE 40165, recorded on 10 October 1927: https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/101915/McCormack_John?Matrix_page=13 [3 minutes 32 seconds]; the photograph of McCormack is also not referenced, but looks to be of him in the nineteen-thirties; for an introduction to John McCormack see his Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_McCormack_(tenor)).

The lyrics to the refrain which is our immediate concern are:

Just a song at twilight, when the lights are low,

When the flickering shadows softly come and go,

Tho’ the heart be weary, sad the day and long,

Still to us at twilight comes Love’s old song.

Comes Love’s old sweet song.

(Lyrics from Bell’s Irish Lyrics page: https://www.bellsirishlyrics.com/loves-old-sweet-song.html; curiously there is a slight difference in the version performed in the film where the singer sings ”when the lights are blue‘! Just a slightly misremembered lyric, or an addition of a shade more melancholy or a further allegedly ‘comic’ working-class malapropism?).

Here is the song and surrounding context in the film – click on the play button to start (I have had to use the colourized version of the film which is now the only one available on YouTube; all Youtube clips play as a loop, so do just click back to the article when you have heard / seen it enough times!):

https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxPGCAnHpQY2Q-3cdfCdnal3eQ6XzSsJ1H?si=9ffqnZUQch4PzGd_

Note the ultra-realist touch of the overflowing dust-bin, which was remembered vividly by Deborah Kerr in an interview some fifty-seven years later: ‘My first kissing chore [in films[ smelled . . .Clifford Evans . . . had to kiss me among garbage cans outside my slum home. Our director was a fiend of realism and those cans stank to high heaven’ (Jim Meyer, ‘Deborah Kerr’ in Screen Facts, 1968, p.6 – cited in Michelangelo Capua, Deborah Kerr – a Biography, McFarland and Co, kindle edition 2010, location 196).

In the film we just get the first two lines of the lyrics of the refrain, and unlike the semi-grotesque performances suggested by the dramatic contexts in the play, are rather finely sung, perhaps by Mrs Jike. The words and tune are very appropriate to what Harry and Helen and Sally and Larry are feeling, but nevertheless, there are still ironies. The song’s ‘flickering shadows’ did not perhaps envisage the gas-lit back alleys of North Street, nor did its ‘sad the day and long’ necessarily intend a decade long Depression. Of course in the structure of the film, this scene is followed by the news that ‘More Factories are Closing Down’ (the headline displayed on the Manchester Evening News 53 minutes 30 seconds in), and that workers are to go on to short-time. Clearly Harry and Helen and Sally and Larry’s hopes and dreams are threatened by economics, just as the sentiments of ‘Love’s Old Sweet Song’ are both entirely valid and rendered ironic by the environment of Hanky Park. This is a slightly different effect from the folk-song in the novel and the play, but an equally well-thought-through moment showing the film’s (and its director John Baxter’s) extraordinary attention to every detail, whether sound or visual.

NOTES

Note 1. For the lyrics of ‘Drive Away Dull Care’ (Roud 13988) see https://mainlynorfolk.info/folk/songs/drivedullcareaway.html . It was collected by Sandy Ives and first sung more widely by the folk-singer, librarian and archivist Joe Hickerson who made it famous – many other singers have recorded it since then (for his Wikipedia entry see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joe_Hickerson and for him singing the song see You Tube https://youtu.be/CcgOorCbW4k). The University of California English Broadsides Index does not bring up anything close to either ‘drive Away Dull Care’ nor the Love on the Dole lyrics: see https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu/ .

Note 2. See the Hymnopod entry for the hymn: http://hymnpod.com/2009/06/04/whiter-than-snow/.

Note 3. See Ben Harker’s discussion of the considerable differences between the two play editions in his article ‘Adapting to the Conjuncture – Walter Greenwood, History and Love on the Dole‘, in Keywords – a Journal of Cultural Materialism, Vol.7. 2009, pp.55-72, freely available at: https://raymondwilliamssociety.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/key-words-7.pdf .

Note 4. For introduction to Harry B. Smith and Jerome D. Kern see their Wikipedia entries (neither list this song in fact but both were so prolific that this is not surprising): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_B._Smith ; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerome_Kern

Note 5. Clip taken with gratitude from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKKXzb5W718 where the accordionist Philip Miles shows the tune can work on an accordion (though a comment says it would be ‘perfect for a pirate wedding’!). I hope Philip Miles will understand my slightly niche need!