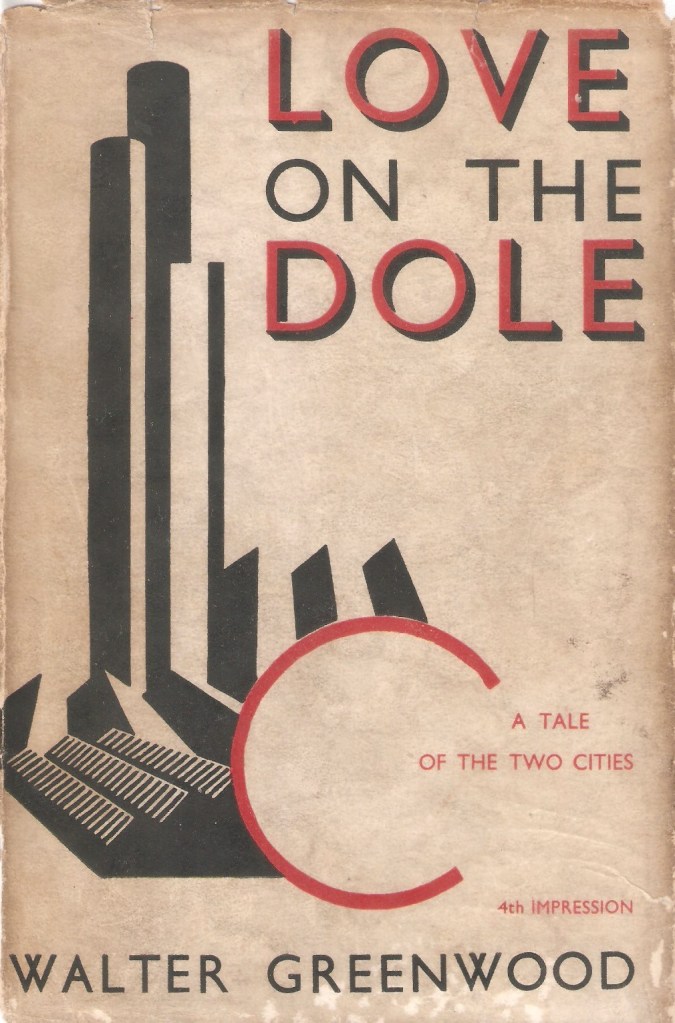

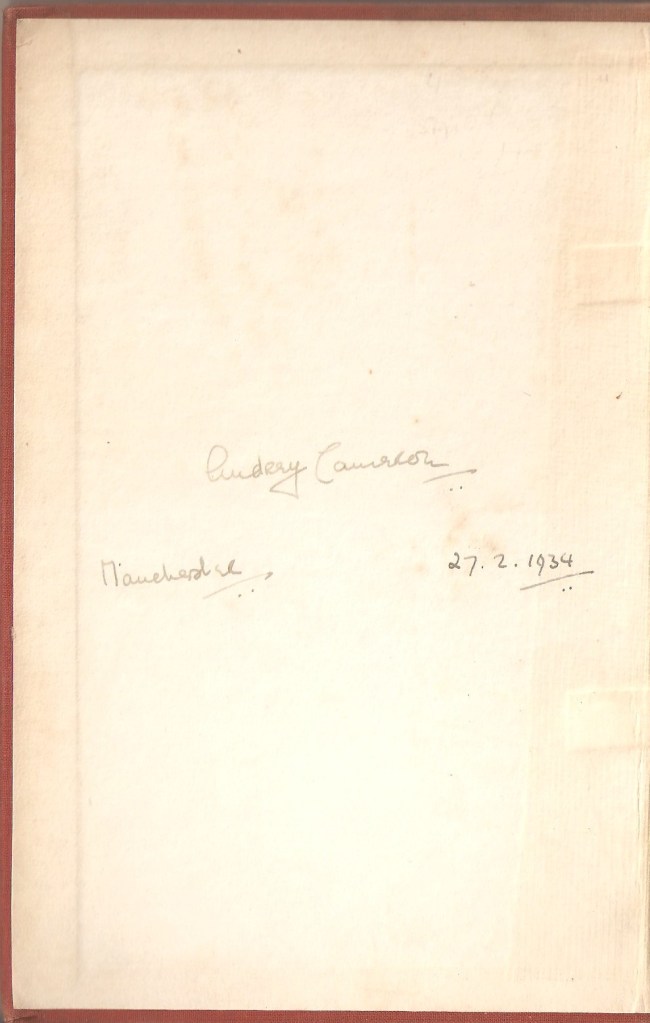

Audrey Cameron (1905-1985) had a varied career as an actress, stage-manager and then BBC producer between the nineteen-tens and the nineteen-sixties, as we shall see at the end of this article, where she will get pride of place. Her contribution to the first production and performance of the play adaptation of Love on the Dole was as the stage-manager. It was clearly an occasion which she regarded as a special one, worth celebrating with a unique spontaneously signed copy of Greenwood’s novel in its first edition and fourth impression. It is signed by Audrey Cameron herself, by Walter Greenwood and the co-author of the play Ronald Gow, as well as by (almost) the entire cast of thirteen (or fourteen) actors, and the producer, Gabriel Toyne (though this term then referred to what we would now most usually call the director).

This article will explore the careers of the director, co-writers, actors, and stage manager who premiered Love on the Dole on that first night, and signed Audrey Cameron’s copy of the novel. It will look at what they did before Love on the Dole, at what they did afterwards and what if any difference Greenwood and Gow’s play made to their careers. In many cases, contributions to repertory theatres were important, though a number also performed extensively in the newer media of radio, film and in due course television. Repertory theatre – that is companies of actors based in one often regional theatre who performed a large repertoire of different plays each year – was actually founded in Manchester, and the Manchester School of playwrights which grew up as a partial result certainly influenced Greenwood and Gow (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Repertory_theatre). As we shall see, some of the actors in the first production of the Love on the Dole left fewer traces than others, while most had successful careers, and one at least became a star of stage and screen.

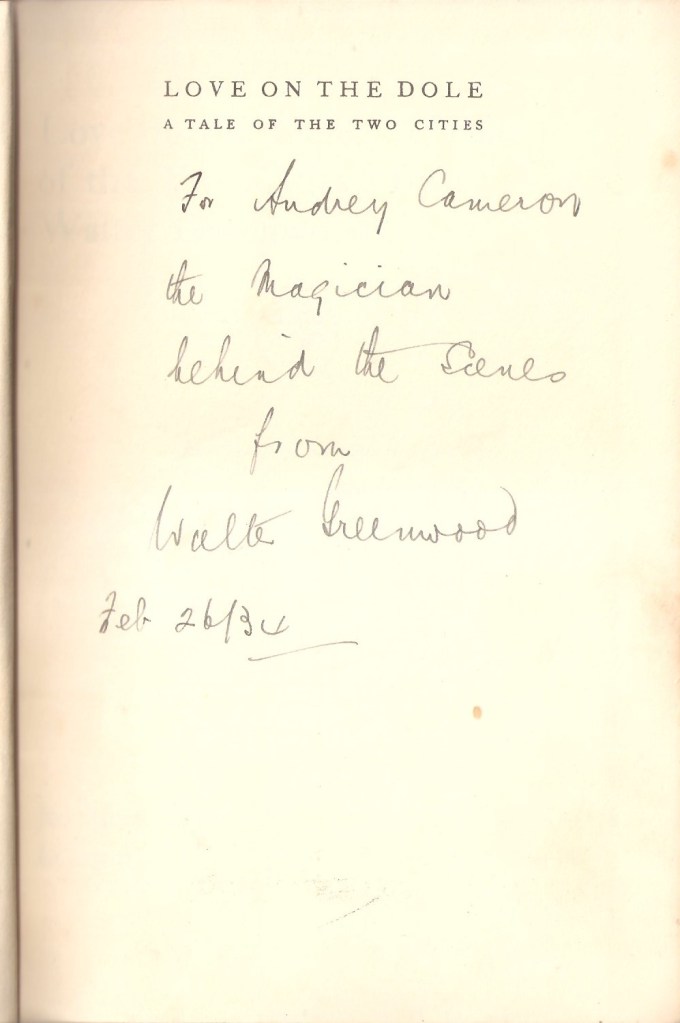

Here is Audrey’s celebratory signed page:

Some signatures are more readable than others, but with the help of the cast list in the first production in the Cape edition of the play (1935) they can all be deciphered:

I shall follow the order of the signatures rather than the cast list in my explorations of these actors, the writers and the producer who jointly realised the premiere of this significant play and collectively marked the occasion. This then is a joint biography of all these witnesses to the first night of Love on the Dole.

1. Gabriel Toyne (director)

So, let us start with Gabriel Toyne (1905-1963), who had a striking and multi-talented career as a stage-manager, director, actor in theatre and film, and perhaps most unusually as a fight director. The IMDB (International Movie Database) has for it an unusually full and useful biography, though it does not mention his role as the first director of Love on the Dole in the theatre. Toyne came from a professional family – his father being the Director of the Brighton Education Committee, though the family also lived in India for part of Gabriel’s childhood. In 1925 Gabriel went up to Corpus Christi, Oxford, to read History. He was active there in OUDS (the Oxford University Drama Society) as well as in fencing (foil) and archery, in which two sports he became a double blue, giving him a genuine command of swordsmanship and the use of the bow, which fed into his expertise for the rest of his career as a fight arranger for theatre and film. He also published a volume of poetry while an undergraduate, aged twenty-two.

As soon as he graduated in 1927, Toyne began working as a director, often in regional theatres, though he also toured Australia and from the early thirties onwards was involved too in film, as both actor and fight arranger. It was presumably the regional theatre experience which brought him to direct the repertory performance of Love on the Dole in in Manchester in 1934. Early in the war Toyne was commissioned into a Gurkha Regiment (perhaps because of his previous experience of India), rose to the rank of Major, and fought against the Japanese invaders in Burma, where he was captured and forced to work on the Burma railway. It was an experience which he, unlike many, survived, but about which he could never bear to speak. He never recovered his full health after this period of extreme privation. After the war, he returned to repertory theatre, including in tours of the Commonwealth, but until his early death in 1963 was mainly engaged in film and TV as a fight arranger.

In the thirties, Toyne was very active in repertory theatre and indeed he was invited to write about his distinctive views and championship of repertory on his appointment to the Manchester Repertory Theatre by the Sheffield Independent newspaper (1 February 1934, p. 6). He saw repertory theatre as having the potential to embody a modern theatre which was accessible and innovative, neither highbrow nor middlebrow nor lowbrow and not primarily commercial, but which delivered something different from (and superior in some respects) to cinema:

Mission —The Breath Of life

I look forward to the time when the Real Theatre, freed from the cloying paraphernalia of the realists, from which the blessed invention of the talkies has relieved us, and released from the sentimental bondage of a system of starred artists, will become also the commercial theatre, and the commercial theatre, as we know it will cease to be.

There will always be enough people who love the drama the Greeks discovered, and the great ones who still present it, and thanks to the universality of the films which have educated the smallest village to expect the best of artists, the number of lovers of high art drama is ever increasing. Finally, the films will have improved to perfection a colour process, a stereoscopic lens, scent and temperature as in the picture shown: in fact, everything short of the real thing – the breath of life; and the good folk will realise the one thing they miss – the people themselves, and they will return to the Real Theatre. (p. 6)

The Stage review praised his direction of the Manchester Repertory premiere of Love on the Dole highly:

Mr. Gabriel Toyne has done his work of producing the play very well indeed. Not only are the scenes skilfully designed, but there are many deft touches in the action that lend material aid to developing the story and toning down its sordid aspects. The result is a play of great sincerity, which will rank high in the category of Lancashire-life dramas. Monday’s hearty reception bv a record audience should give a welcome impetus to the movement for placing this Repertory on a permanent basis (1 March 1934, p.12).

This sees Toyne as playing a key role in translating the script from page to stage, though one might note too the curious praise that he tones down ‘its sordid aspects’ – a terminology which would later haunt the British Board of Film Censors’ judgement in 1934 and 1935 that a film adaptation would be completely unacceptable. In effect, this praises Toyne for being a gatekeeper who undermined harsher points in the play’s critique of current British life. It does though see the play as so important and well-received that it may help establish the currently ad hoc Manchester Repertory Theatre longer term.

Oddly, Toyne’s career at the Manchester Repertory Theatre did not last long beyond this clearly great success which had attracted national attention. On 3 July 1934 the Manchester Evening News announced in a headline ‘Gabriel Toyne to Leave – Manchester Repertory Theatre Surprise’ (p. 9). The writer of the column ‘Roderick Random’ explained that the chairman of the Directors of the company, Mr Vernon Walker, gave no reason for the non-renewal of Toyne’s contract, and then goes on to express his own personal admiration for Toyne’s work at the theatre, especially with innovative uses of lighting and set design and in presenting plays in a ‘fresh and vigorous manner’, naming Love on the Dole as one of his successes. Clearly, however, something had gone wrong between Toyne and the directors (I wonder if they considered him too innovative?). However, this was not the end of Toyne’s involvement with the play, because he continued as producer for the Vernon-Lever touring production which visited most towns and cities in Britain from October 1934 onwards (as we can see for instance from an advertisement for the play in the Todmordern & District News on 19 October 1934, p. 2). It seems likely that Greenwood and Gow’s play, widely regarded as serious, innovative, daring, accessible and entertaining, with a large element of ensemble playing, matched well with Toyne’s own views of what a modern ‘real theatre’ should offer for the broadest possible audience.

2. John Byrne (Charlie)

John Byrne played the relatively small role of Charlie, the side-kick of Sam Grundy the bookie, so it is not surprising that he was a less famous / less reported actor. However, Greenwood must have been happy with his contribution to Love on the Dole, since he was cast in further and sometimes somewhat larger roles in several subsequent Greenwood plays, as well as in a play which was sometimes compared to Love on the Dole, James Lansdale Hodson’s Harvest in the North (1935), in which he played the walk-on part of an ambulance man. The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer picked him out for praise for his role as Harry Evans in Greenwood’s Give Us This Day (the play version of the novel His Worship the Mayor) in a production in Manchester:

The author has kept the same atmosphere as in Love the Dole. One finds the same background of crushing poverty and the same victims struggling hopelessly against the dread unemployment . . . The play would be almost unbearably depressing were it not for the relief Introduced by Miss Winifred Acton, who carried off the honours with brilliant study practical and plain-spoken woman and, in lesser degree, by her husband, played by John Byrne (24 March 1936, p. 4).

The Era made a similar judgement in its review of the play: ‘It is equally impossible to deny that the honours of the production were appropriated by Winifred Acton and John Byrne as Mrs. and Harry Evans, who enlivened things with real comedy’ (25 March 1936. p.3). I have not so far found further references to him in stage plays after 1936, but he may be the John Byrne listed in the cast of a radio play on the BBC Northern service in October 1937. This was ‘Cattle Boat – radio drama of an Atlantic Crossing’ (Evening Despatch, 11 October 1937, p. 3). If he did not make it to the big time, I am hoping that he continued as a working actor. Perhaps not surprisingly, I have not so far found a photograph of him.

3. Edmond W. Waddy (a Policeman)

Edmond W. E. Waddy appeared in a Manchester Repertory Company production of the farce It Pays to Advertise by Walter Hackett and Roi Cooper Megrue in 1933 (1). The Stage review praises him in what sounds a larger role than he had in Love on the Dole: ‘Edmond W. Waddy is exceedingly funny as the energetic publicity manager’ (27 July 1933, p.4). He continued to play the part of a policeman in the touring production of Love on the Dole throughout 1934 and 1935. The Huddersfield Daily Examiner picked him out for praise when the play came to the Huddersfield variety theatre, the Palace, saying that ‘we liked immensely Edmond W. Waddy’s quietly etched in picture of a policeman’ (20 November 1934, p.8). Waddy and Beatrice Varley (see her entry below) were a married couple and were two of only four actors to transfer from the Manchester Repertory production into the Garrick London production.

4. Douglas Quayle (Larry Meath)

Douglas Quayle (1898 -1957) was a successful actor with a long career on the stage, though he also did some later work in television. He consistently worked in repertory. The first reference I can find to him is as playing the male lead, Captain Matt Dennant, in Galsworthy’s play, Escape (1926) about a man who accidentally kills a plain clothes policeman whom he sees apparently harassing a woman. He is then sent to Dartmoor, but escapes and in a series of scenes the play follows the ways he is helped or obstructed or treated by characters from a range of social backgrounds. This production was at the Theatre Royal Hanley in 1929 (Staffordshire Sentinel, 18 April, p.5). (2)

He appeared in a further Manchester Repertory Theatre production a little after Love on the Dole. The Stage reviewed A.A. Milne’s play Michael and Mary, commenting that Quayle ‘is very amusing as the policeman with literary ambitions’ (21 June 1934, p.13). In 1936 Quayle presented a series of repertory productions in Newcastle with Hector Ross (the Stage 11 June 1936, p.8) By November 1937, he was co-leading a Repertory company in Torquay, Devon, in a more formal partnership with Hector Ross, putting on a series of plays at Torquay Pavilion, including Noel Coward’s Private Lives, J.B. Priestley’s Laburnum Grove, 1933 (Torquay Times and South Devon Advertiser, 26 November, 1937, p.1 and subsequent issues). (3)

By 1947 Quayle is being described as a ‘prominent artiste’ in a production of Esther McCracken’s play No Medals (1944) at the New Theatre, Northampton, which the preview says ‘pictures in vivid fashion the wartime experiences of a particular household’ (Market Harborough Advertiser and Midland Mail, 16 May 1947, p. 15). He is still in repertory in May 1951 when ‘Douglas Quayle and the County Players’ are reported as appearing at the Theatre Royal Lincoln in a revival of the musical play Smilin’ Thro’ (Lincolnshire Echo, 4 May 1951, p.2). (4) The repertory company also gave a series of other plays in the same venue, including Macbeth in June. One of Quayle’s latest performances was as Edward IV in a play by Mary Preston, Richard’s Himself Again, which rewrote Shakespeare’s play with Richard as a more positive figure. This was produced at the New Gateway Theatre in January 1957 by the ‘Venturers’ company, though sadly I am not sure where this theatre was. The review comments that ‘the dying Edward IV was expressively depicted by Douglas Quayle, though his bearing was more kingly than his diction’ (The Stage, 24 January 1957, p. 10) . His brief obituary in The Stage (29 August 1957) records that he died on 17 August and gives us a few more details of his whole acting career, saying that he had acted with Sir Barry Jackson’s Birmingham Repertory Theatre early in his career and that he had recently been part of Donald Wolfitt’s company which had revived a number of renaissance plays including two in which Quayle had a part: Ben Jonson’s Volpone (printed 1607) and Philip Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts (printed 1633).

5. Jean Winstanley (Helen Hawkins)

Jean (Beattie) Winstanley was born in Urmston in Lancashire in 1913, and studied sculpture at Manchester Regional College of Art and Design, before going to RADA to study acting, completing her course in 1934. Her role in the premiere of Love on the Dole was clearly therefore one of her first roles (IMDB), though there was at least one also with the Manchester Repertory Company earlier in February 1934. She and a large part of the Love of the Dole repertory cast had appeared in play called Destination Unknown by J. Martin. The Stage reviewer praised most of the actors but expresses barely concealed reservations about the piece itself, which it says ‘runs on melodramatic lines’, has one role which is ‘a trying part’, and a title the import of which is ‘difficult to appreciate’ (The Stage 8 Feb 1934, p.6). The review also reports innovative staging by the producer, Gabriel Toyne, with succeeding scenes playing on an upper and lower level to avoid delays from cumbersome scene changes.

It was, of course, a feature of repertory companies that they performed a relatively large number of different plays within a short period at the same theatre, unlike most touring companies This was a challenge for repertory actors who kept having to learn new parts rapidly. Manchester Repertory Company was no exception for, despite the great success of Love on the Dole in February 1934, it had to keep going with its schedule. Jean Winstanley played a leading part in April 1934 in Elswyth Thane’s The Tudor Wench, with Gabriel Toyne in this case performing the male lead role alongside her. Indeed, the Stage review noted that ‘both the principals, Jean Winstanley and Gabriel Toyne had to respond to repeated calls’ while also remarking that Toyne also gave the audience a thrill with the reality of the duelling scene with Sir Thomas Seymour’ (26 April 1934, p. 13). A new month, another play. In May 1934, the Manchester Repertory company produced April in August, by Clifford Bax, again including Jean Winstanley, which also appeared with the same cast at the Phoenix Theatre in London for one Sunday performance only.

In 1937 Winstanley made her first film appearance in a production which seems to have been quite a success in Britain, though it is not now well-remembered. This was a film called Said O’Reilly to McNab, produced by Gainsborough Pictures, directed by William Beaudine, and released in July 1937 (according to IMDB – the poster below gives December 1937). The screenplay was by Leslie Arliss and others, and the stars were two British comic actors, Will Mahoney and Will Fyffe, both with music hall backgrounds as respectively Irish and Scottish ‘characters’. The two young romantic leads were played by Jean Winstanley and James Carney. The film is mainly a comic vehicle for Mahoney as O’Reilly, an urbane businessman (and as it turns out fraudster), and Fyffe as McNab, a successful Scottish businessman who is careful with his money, and who is unwilling to allow his daughter Mary McNab (Jean Winstanley) to marry O’Reilly’s son, Terry (James Carney) unless he can show he has a good job or at least parental monies. In fact, O’Reilly senior and his female accomplice Sophie (Marianne Davis) have no money at all, and are wanted by police in the US for fraud, which is why they are currently on the run in Scotland. They succeed not only in persuading McNab to allow the two young lovers to marry, but also in getting McNab to fund the manufacture of a patent slimming pill of their own invention (partly by winning a bet on the outcome of a golf game) – which bizzarely becomes a great success, providing both families with assured fortunes and jobs.

Plot and characterisation are decidedly thin in places, with an emphasis on comic set-pieces between O’Reilly and McNab, and indeed the roles played by Jean Winstanley and James Carney are really quite basic, with very little required of them beyond looking young and good-looking, and therefore in this world of mere stereotypes, sympathetic. It was presumably a valuable opportunity for Winstanley, though, as a first breakthrough into the film world. There was a VHS release of the film in a British Classics series, and there is currently a version uploaded on YouTube (though I do not know with what copyright status). (5) From my point of view, it is very good to be able to see a record of Jean Winstanley acting. Overall, it is a watchable and reasonably entertaining film, though it did not seem to me very sophisticated, but see the contemporary professional view below that it was an unusually slick production for a British film of the period (I can see that Will Mahoney and Marianne Davis give slicker and more Hollywood style performances while Will Fyffe and Ellis Drake as his wife give performances in a more British music hall mode). It was widely screened between 1937 and 1939, and most regional newspapers gave it a positive review or notice akin to that carried by the West Middlesex Gazette:

The story of Said O’Reilly to McNab is a lively one, bringing to the screen the wit of two nations recognised the world over as the homes of funny stories. The film has been directed at a fast pace with a wisecrack in every line, and is put over by two of the greatest living exponents of Irish and Scotch humour. Supporting Will Mahoney and Will Fyffe are . . . Jean Winstanley and James Carney, responsible for the romantic interest, and Marianna Davies as the Irishman’s secretary (18 December 1937, p. 16).

Kinematograph Weekly in its review written to inform Cinema Managers took a similar view overall (though it thought the two lovers were merely ‘adequate’):

Production – this is a triumph for Beaudine; all the slickness and polish we expect from an American production is here. The story of the golf match is told by a true artist, and at no moment is there a pause. Pictorially. too, the work is extremely satisfactory (1 July 1937, p. 31).

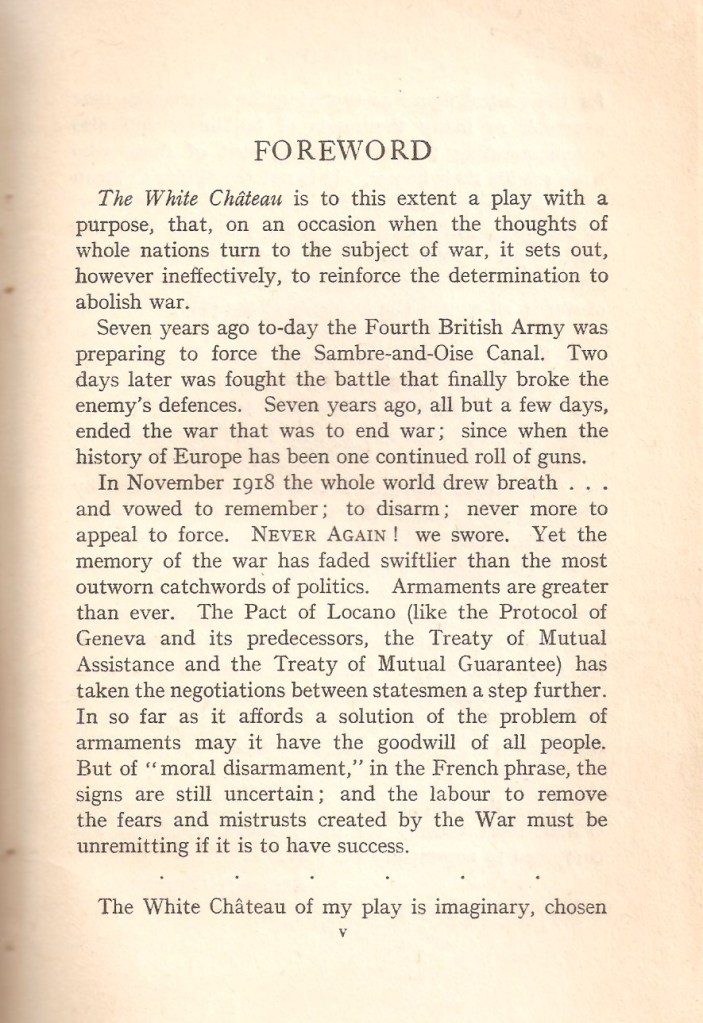

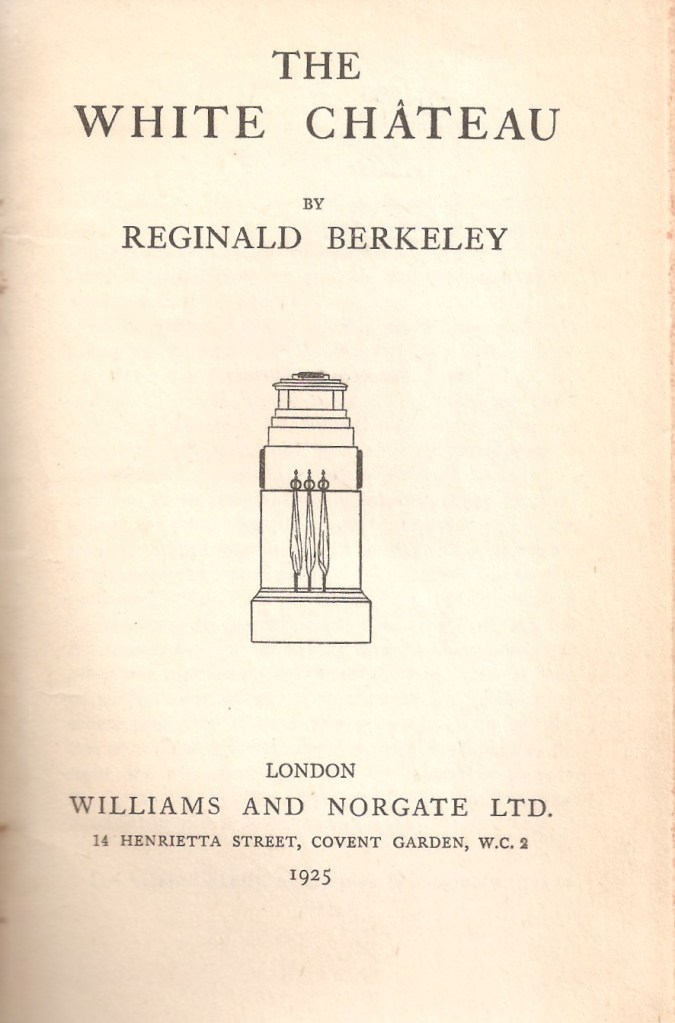

In fact, Jean Winstanley does not seem to have appeared in any further films for cinema, but she did have a role in a rather extraordinary (and very different) live broadcast drama made for the BBC’s pre-war television channel. This was a live television production of a play called The White Chateau by Reginald Berkeley, first performed on BBC radio on Armistice Day in 1925, and then adapted into a theatre play by its author.

The BBC television broadcast was performed thirteen years later for Armistice Day (11 November) 1938 and went on air from 9.00 to 10.30 pm. It included ‘verses’ by T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, Wilfred Owen, Ezra Pound and Ceil Day Lewis (these are not in the original radio play published script, so were presumably added as a new element for the television production). Though relatively few people had televisions at this point, the broadcast seems to have had a considerable impact. Some considered the play in its various forms a significant anti-war play (‘classed among the best plays of the century’ reported the Yorkshire Evening Post on 17 November 1934, p.5), and the Foreword (below) clearly makes a claim for the seriousness of its intent to reinforce post-war support for the refusal of another war. The initial radio version was certainly seen as being a success, the Dundee Courier writing that ‘it proved so popular in that medium that it was decided to write a stage version for the West End’ (25 April 1927, p.8).

In addition, the television broadcast led to considerable publicity for the more immediate reason that police stations near the studio were besieged by callers asking what the explosions were and saying that many women and children were terrified by the noise, apparently caused by the discharge of two howitzers from a Territorial artillery battery:

Radio Guns Reduced to Fireworks, by the Radio Correspondent

TERRITORIAL artillery taking part in the television programme last night used fireworks instead of blank ammunition. As each gun fired there appeared on the screen a brilliant flash which was followed by a cloud of smoke, but there was no heavy report, merely a poof. This toning down of the realism in connection with Reginald Berkeley’s play, The White Chateau followed Friday night’s complaints from people living in the Alexandra Palace district. I watched both performances of this television programme and certainly did not notice that the absence of real gunfire in any way upset the effectiveness of the play. A BBC. official explained afterwards that the fireworks used made practically no noise. ‘We did not wish to upset people around here again. and I can assure you the noise was very different from Friday night.’ he said (14 November, p.11).

Television sound effects were clearly in their infancy, but a production note suggests this broadcast was exceptionally daring and used contemporary resources to the full:

For The White Chateau, the big-scale war-play televised last month Studios A and B at Alexandra Palace were used. Sound and vision from these and from the artillery attack carried out in the grounds of the Alexandra Palace were sorted out by the central control room, presided over by D.H. Munro, the production manager (‘Engineers in Ecstasies’ by The Scanner, Radio Times, 2 December 1938, p.17, quoted on the British Film & Videos Council notes on The White Chateau: http://bufvc.ac.uk/screenplays/index.php/prog/1016 ).

The White Chateau was published by Williams and Norgate in 1925 (See images above and below). Jean Winstanley is listed in the television cast as playing the part of Violet Cording, who is it turns out a minor character, largely because after the first scene of peace in the chateau, the subsequent five scenes are wartime scenes populated almost completely by male army officers, NCOs and soldiers after the chateau has been commandeered and then surrounded by trenches. Violet Cording is the fiancée of the heir to the chateau, Jacques Van Eysen, who she is visiting for the first time and being shown the neighbouring city and its fine cathedral. She fades out of the play after the first three pages of the script, as does the entire Van Eysen household. Still, this was an important and innovative broadcast of a drama designed to engage, as the Foreword suggests, and perhaps controversially, with a national day of memorialisation which had become a new and important part of British culture after 1919, when the two minutes’ silence was first observed at Buckingham Palace. The Cenotaph (’empty tomb’), originally built in wood as a temporary monument in 1919, was incorporated into the public acts of remembrance in November 1920, after being rebuilt as a permanent monument in stone to a design by Sir Edwin Luytens. (8) The printed edition of The White Chateau referred to the Cenotaph in a line-drawing on its title page:

Despite these interesting openings, as far as I can see Winstanley’s acting career on stage or screen seems to have wound down at the end of the thirties. This may well be due to her marriage and then parenthood. The Manchester Evening News reported in 1936 (5 November p.1) that Jean Winstanley and a John Ford are to marry after acting together as understudies in a production of Romeo and Juliet at the New Theatre, London. The same paper subsequently reported the birth of their son (17 September, 1940, p. 5).

6. Grenville Eves (a Young Man)

Grenville Eves had a number of minor parts in Manchester Repertory and other company productions in the thirties, and while not leaving prominent traces of his career seems to have continued on stage and by the later nineteen-forties was playing larger roles in serious theatre, including in George Bernard Shaw’s The Doctor’s Dilemma at the Prince of Wales Theatre (Western Mail, 21 June 1948, p. 21). He is advertised as having a leading role too in a year-long run of Lesley Storm’s play about a wealthy society woman who shop-lifts called Black Chiffon at the Westminster Theatre, London in 1949 to 1950. His father was the well-known portrait-painter Sir Reginald Grenville Eves R.A. (1876-1941 – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reginald_Eves). There is a newspaper report that Grenville Eves served in the RAF with a barrage balloon unit during the war, where he also contributed to entertainments for the troops, partly with his impersonations (‘Round the Memorial – Gossip of the Week, by Observater’, Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 23 January, 1943, p. 4).

7. Clifford Marle (Mr Hardcastle)

Clifford Marle (1883- 1936?) was an experienced actor who had appeared during the nineteen-twenties in a number of silent films, including two shorts The Adventures of Lieutenant Daring R.N. : In a South American Port (1911) and The Gentleman Ranker (1912) and a decade later as Phipps in the feature film adaptation of H.G. Wells’ novel about pioneering cyclists, The Wheels of Chance (1922). (6) He also appeared on stage during that period in leading roles, for example playing Christopher Brent in The Man Who Stayed at Home in May 1917, a popular play about German spies and a British spy-catcher, and Raffles in E.W Hornung and Eugene Preserby’s 1903 adaptation of Raffles (the Amateur Cracksman) in 1922. (7) By the thirties though he was was working mainly in repertory theatre both as a producer and an actor. The Birmingham Daily Gazette notes his role in a production of Arthur Wing Pinero’s Trelawney of the Wells: ‘the star was Clifford Marle, a seasoned actor who having played all sorts of parts all over the world, joined the Birmingham Repertory Company last Autumn’ (30 March 1936, p.3). Before that Marle had already been appearing for at least a decade with the Manchester Repertory Theatre, and the Stage noted in February 1931 that, as well as playing the role of Fluther Good, Marle had taken over as producer of Sean Casey’s The Plough and the Star after the original producer was taken ill (5 February 1931, p. 15). By 1934 Marle was fifty-two, so was a suitable age to cast as a father with two late-teenage children – the Stage review of the Manchester Repertory premiere praised his ‘excellent’ portrayal of Mr Hardcastle (1 March 1934, p.12).

8. Beatrice Varley (Mrs Bull)

Beatrice Varley (1896-1964) was an actress who worked for a long period in diverse kinds of theatre, but for whom her appearance in the Manchester Repertory premiere of Love on the Dole was a distinct turning point. Her husband Edmond W. Waddy (they had married in 1921 – see above) gave a detailed account of her life for her obituary in 1964 (she had given her last performance on Granada TV the week before). Beatrice was born in Queen’s Park, Manchester and went to work in a cotton mill aged fourteen, but because of her singing voice soon went onto the music hall stage full-time (Middlesex County Times, 11 July 1964, p. 14). As early as 1909 (when she was only thirteen!), a Kinematograph Weekly review notes her live contribution to a mainly cinematic show at West’s Picture Palace in Bournemouth: ‘Miss Beatrice Varley is in the last week of her engagement, being highly successful in her descriptive songs’ (7 October 1909, p.39). She subsequently also played the piano, violin, xylophone and post horn in music hall performances, before becoming a regular repertory actor. She was very much a character actor and often had relatively minor parts, but usually ones with considerable impact. She appeared in dozens of plays, usually in striking character parts, and at least seventy films, some quite notable, as well as dozens of television plays, and adaptations and some appearances in ‘soaps’. It is noticeable that though she does have a Wikipeda entry, it makes no reference to her stage career, which clearly spanned some fifty-four years, though the entry does carefully and usefully list all her film roles (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beatrice_Varley). Edmond W. Waddy was very clear about the impact on her career of appearing in Greenwood and Gow’s play: ‘It was as Mrs. Bull in Love on the Dole . . . that Beatrice Varley became a name on theatre-goers’ lips’ (Middlesex County Times, 11 July 1964, p. 14). Indeed she was widely praised in contemporary reviews:

There are some artists, previously unknown to me, in this cast who are so good that to associate acting with them seems out of place. Julien Mitchell as the father, Alex Grandison as his eighteen year old son, and Beatrice Varley as a friend of the family do not appear to be playing parts, they are the people themselves (the Bystander 13 February 1935, p.8).

She was still appearing in repertory theatre productions until at least 1962, as for example her performance, aged 66, in a lead role of the stage version of Keith Waterhouse’s Billy Liar (novel 1959, play1960, co-written with Willis Hall) at the Windsor Theatre Royal. The useful programme also included a photograph of Varley and a helpful overview of her career.

9. Olga Murgatroyd (Mrs Jike)

Olga Murgatroyd was appearing regularly in regional theatres from at least 1923 onwards. Though one might expect Mrs Jike (like Mrs Bull) to be played by a character actor, Olga Murgatroyd does not seem to have specialised in that kind of acting, and was often praised for playing leading and serious roles, including for example the part of Elizabeth Barrett Browning in the play by Rudolf Besier:

The fine dramatic qualities of, The Barretts of Wimpole Street are being thoroughly displayed this week . . . at the Theatre Royal, York. The atmosphere of the Wimpole Street menage, dominated by the supreme egoist, Edward Moulton Barrett, is authentically captured and pervades the whole play. Olga Murgatroyd revealed complete understanding of the character of Elizabeth, torn by two loyalties, and Duncombe Branson was a convincing Robert Browning whose logic finally resolved all her doubts. Arthur Bowers was responsible for a very penetrating study of Edward Barrett, and the suggestion which the play conveys of complexes in his character were just hinted at and not obtruded. He displayed considerable powers of emotion in the final passages. The three leaders were supported by a very capable company (Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 11 January 1933, p.4).

In fact she was perhaps surprisingly praised in related terms when she played Mrs Jike in Love on the Dole too, as in this review headed ‘Sincere Acting’ of a 1938 production by the Court Players, a repertory company, at the Hastings Pier Theatre (an interestingly ‘broadbrow’ venue) when she clearly reprised her Manchester Repertory role:

Three fascinating studies of low life are given with great skill by Olga Murgatroyd, Dulcie Langham and Jean Lester as Mrs. Jike, Mrs. Dorbell and Mrs. Bull, and Douglas Ives is equally true to character as Sam Grundy, the opulent bookmaker (Hastings and St. Leonards Observer, 30 April 1938, p.8).

In 1939 Olga Murgatroyd continued to appear in serious leading roles including with the Court Players:

Jane Eyre next week at the Pier Theatre is a play with very strong appeal The world-famous drama . . . was produced at the Queen’s Theatre, and owing to its success was transferred to the Aldwych. It was adapted by Helen Jerome from Charlotte Bronte’s novel. No doubt the great majority of people have read this story and it will therefore be of double interest to see it enacted on the stage. It is full of strong and thrilling situations. The character of Jane Eyre will be played Olga Murgatroyd, who should prove ideal in this part, requiring as it does the portrayal of a frail woman capable of strong dramatic feelings (Hastings and St. Leonards Observer, 15 April, 1939, p. 8)

I have not however found continuing traces of Olga Murgatroyd’s career during the war or after.

10. Ronald Gow (co-author)

Ronald Gow (1897-1993) gave an interview in 1934 to the well-known drama critic R.B. Marriott, who worked for The Era (an important theatrical paper). Marriot asked Gow to talk about his career thus far:

RONALD GOW, the Bowdon (Cheshire) school-teacher, who had a considerable artistic success when his play, Gallows Glorious, was put on at the Shaftesbury Theatre, London, a few months ago, told me something about himself, his successes, and his ambitions when I talked to him at his home at Bowdon. After writing one-act plays for several years, Gallows Glorious was accepted by a London manager, and Mr. Gow decided to give up his job at the Altrincham High School and to devote his time to playwriting. ‘As I had gone so far, I thought it better to go all the way,’ he said. ‘I took a risk, I know, and, as it turned out, Gallows Glorious didn’t make me any money. In New York it was an utter failure. The man who put it on lost 10,000 dollars, and had to go to Palm Beach to recuperate!’

‘But the London and New York Press reviews were so encouraging that I made up my mind to devote the whole of my working time to writing plays. Since then I have written Love on the Dole, from Walter Greenwood’s novel, and an eighteenth-century comedy. Love on the Dole has been packing Manchester and Stockport theatres for several weeks, and when I saw it at the Metropole Theatre the audience was exceedingly enthusiastic. The eighteenth-century comedy will be produced at the Embassy Theatre probably in July. It is rumoured that Ronald Adam, the Embassy director, will take one of the principal parts.

So far, the risk that Mr. Gow took when he retired from teaching, seems to be well justified, because Love on the Dole, is due in London in a few weeks . . . Wendy Hiller, a brilliant northern discovery, will be seen in the part of a Lancashire lass. Miss Hiller has made a great success of it in the North. I asked Mr. Gow whether any of his plays are to be filmed. An American company has been after Gallows Glorious, and a certain English company is practically certain to take Love on the Dole . . .’

Mr. Gow has made an appreciable sum of money out of Love the Dole, from Lancashire theatres alone, and the author of the book [ that is Greenwood] has been signed up by Jonathan Cape for his next three novels. A few months ago he was out of work and had nothing very exhilarating to look forward to. ‘I began writing one-act plays for schoolchildren,’ Mr. Gow said when I asked him about his efforts. ‘My first I sent to French’s [the drama publishing company ] and it was accepted immediately. I have written many more. My first three-act play was accepted without a lot of effort . . . I write my plays for entertainment and for theatre value. If I happen to say anything worthwhile in them, all the better.’ (The Era, 20 June 1934, p.14).

In some ways Gow is here a little modest about his school-teaching career, which had involved considerable creativity and innovation. He had written not only one-act plays suitable for school performances, and published them, but also in the nineteen-twenties made three short silent films with his classes. Two were about life in pre-historic Britain: The People of the Axe (1928) and The People of the Lake (1929), while the third, The Man Who Changed his Mind (1929) was an adventure story about boy-scouts with the coup of a short guest appearance by Robert Baden-Powell, and a fourth, The Glittering Sword (1929) was a parable about disarmament set in the middle ages.

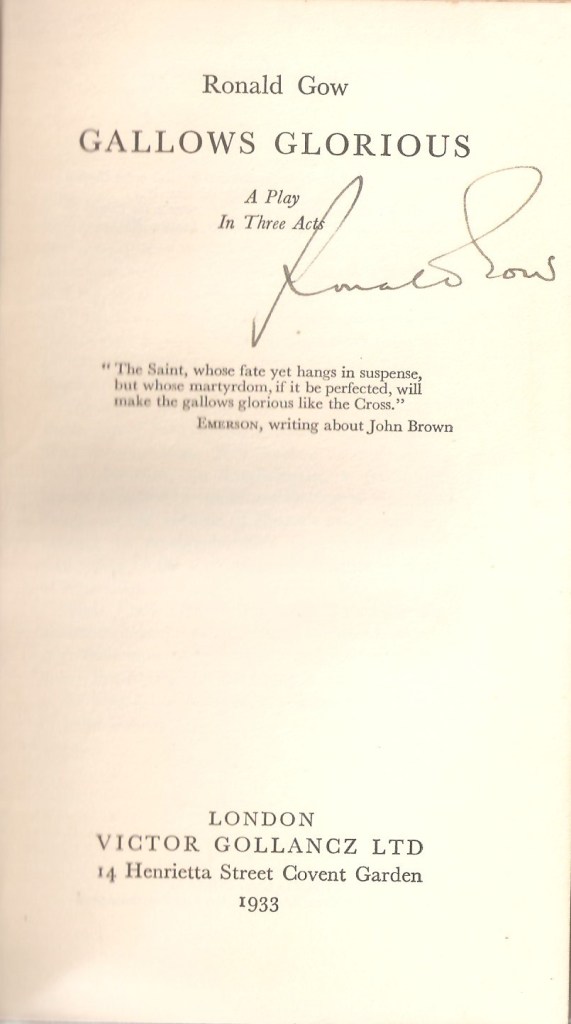

In 1933, his first full-length three act play Gallows Glorious was accepted for production first by the Croydon Repertory Theatre and then by the Shaftesbury Theatre. The play was based on the life of the significant radical slave abolitionist John Brown (1800-1859), the hero of the song ‘John Brown’s Body’, an evangelical Christian who had come to the conclusion that slavery was fundamentally contrary to the teachings of Bible, and to the U.S. Declaration of Independence, but also that it would never be abolished by pacific means, so that radical action including armed force was necessary. He fought against slavery in many different ways, but became prominent as a leader of armed resistance to aggressive supporters of slavery, initiating a number of successful and often lethal raids against the opponents of abolition, as well as attempts to free and arm the enslaved. He was finally captured at the famous raid on the Harper’s Ferry armoury, convicted of treason and hanged, but naturally became a hero for many abolitionists and victims of enslavement. This was clearly a substantial theme and hero for a socially-conscious drama, and proved a great success in Britain if not in the US. Many British newspapers published highly positive reviews supporting both its message and its power as a piece of theatre (despite of course Britain’s own position then as a colonial power ruling over many millions of subject peoples):

Gallows Glorious . . . is characterised by the rare qualities of depth and sincerity. It is a forceful and moving work, and London audiences are indebted to the Croydon Repertory Theatre for a production whoso success has brought it to the West End. The story relates—and if any theatrical embellishments are used they merely serve to emphasise the underlying theme – the struggle of that immortal hero of American history, John Brown, against the institution of slavery. . . . Mr Gow has given to the central figure of the play a superb dignity, and a dominating fanaticism that has yet the spirit of the visionary . It is an exciting piece. Events move swiftly, the raid on Harper’s Ferry and John Brown’s defeat, though ‘his soul goes marching on’ are essentially the stuff of drama (The Scotsman, 24 May 1933, p. 16).

From Gow’s own account of his career in The Era, it is clear that Gallows Glorious was a considerable critical success (it was immediately published by Gollancz), but not a financial one – though Gow had staked his future on it (it was not in fact filmed as a cinema production).

Like The White Chateau, Gallows Glorious was clearly thought a significant work by the BBC which invested in a TV broadcast production put on air on 18 November 1938 (as it happened Audrey Cameron was a member of the cast – see http://bufvc.ac.uk/screenplays/index.php/prog/494). Gow acknowledged that it was the play of Love on the Dole which really launched his career as a professional playwright who could earn a living from his craft (if he and Greenwood took an equal share in the play’s success then it may have brought them up to £5000 each in 1935 – see: https://waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com/walter-greenwoods-finances-and-love-on-the-dole/ .

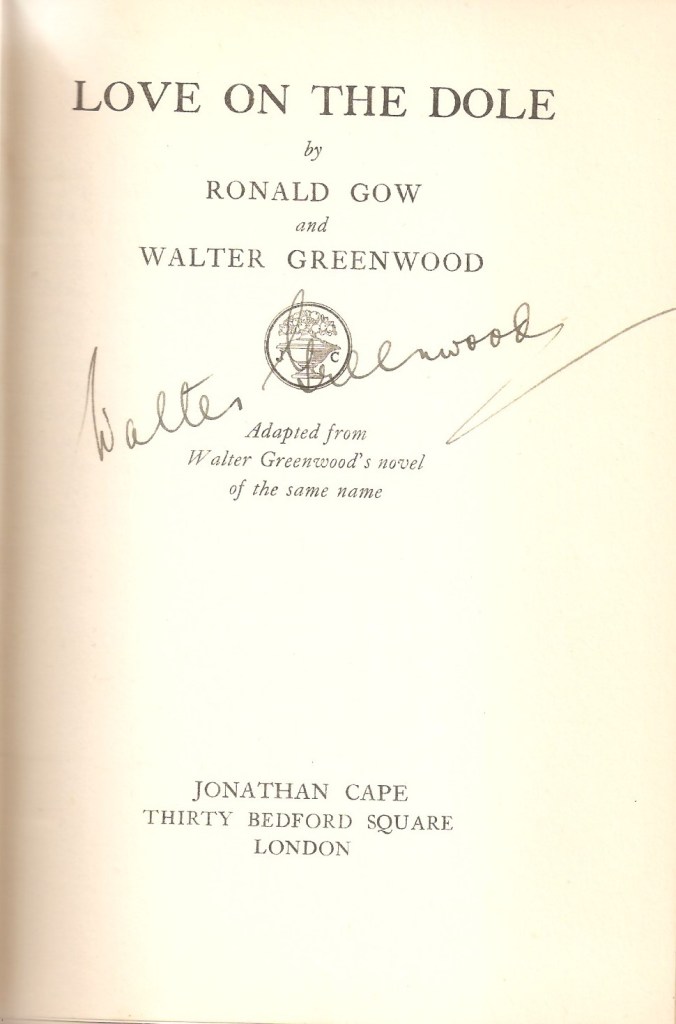

While Gow may have been over-modest about his career as a school-teacher, the same might not be true of his claims about his contribution to the play of Love on the Dole. While it is true that it was Gow who approached Greenwood to suggest working together on a stage adaptation of Love on the Dole, he represents himself here as the sole author and adapter of Greenwood’s best-selling novel, with no active role for Greenwood in writing the play (a view echoed uncritically in his Wikipedia entry which asserts that ‘he wrote Love on the Dole based on Walter Greenwood’s novel’). (9) The play has however always been produced and printed with a joint attribution thus:

This text clearly implies that though the play is adapted from Greenwood’s novel, the play is also co-authored by Gow and Greenwood. What we do not know is exactly how they jointly worked on the play-text, but I certainly assume that it was a collaborative task, even if we cannot know the precise nature of the division of labour. Gow’s theatre aesthetics, as stated in The Era article above in 1934, do seem well-matched to those of Greenwood, though perhaps the novelist might have given the ‘message’ greater priority: ‘I write my plays for entertainment and for theatre value. If I happen to say anything worthwhile in them, all the better’ (I will not add a separate biography of Greenwood to this article – it seems better to refer readers to my biography of him elsewhere on this site: Walter Greenwood: a Biography).

Certainly, after Love on the Dole Gow established himself as a professional playwright and screenwriter first for cinema and then later for television. He and the star of the stage version of Love on the Dole, Wendy Hiller, also married in 1937, so the play had a considerable impact on his life in several ways. She made her first film appearance in a film with a story by Gow in the same year, Lancashire Luck (directed by Henry Cass, produced by British & Dominions Film Corporation, general release date 30 May 1938 – see IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0029107/?ref_=ttrel_ov) .Gow wrote another Lancashire play, Ma’s Bit of Brass (1938), which was later broadcast as a television product by the BBC in 1948 (Beatrice Varley – see above – took the part of Aunt Norah, so perhaps she and Gow had kept in touch after Love on the Dole?). (10) He also wrote the book for a musical by Harry Par-Davies based in a Welsh village and called Jenny Jones, which had a reasonably successful run in the Brighton and then London Hippodrome in the last year of the war, between October 1944 and January 1945. (11) He wrote a number of adaptations of classic novels for BBC television in the nineteen-forties and on into the mid-nineteen-sixties, of which several starred Wendy Hiller.

11. Eileen Draycott (Mrs Hardcastle)

Eileen Draycott (1893-1963) was also born in Lancashire, and worked at Manchester Repertory Theatre for some years before she appeared in Love on the Dole in 1934. The Manchester Evening News interviewed her in 1939 when she returned to the theatre in a touring production of Armitage Owen’s play For Goodness Sake! (1939), and described her as ‘the doyen of Manchester Repertory Theatre actresses’:

‘I love every stick and stone of the place and when I walk on the stage I shall know that I have friends in the auditorium’, she said to me to-day. Miss Draycott left the Repertory Theatre in 1936 after the season at the Prince’s Theatre. I had been there for twelve and a half years’, she told me.’ Then I was very ill, and when I got better and had the offer of going on tour I jumped at It. I felt I should have a better chance of recovery if I got away for a time . . . I spent a small lifetime at the Rep and saw many changes, and whenever I look in it is still the same dear old place.” Lately Miss Draycott has been doing a great deal of radio work. She has a house little more than a stone’s throw from the Repertory Theatre (16 January 1939 p.2).

Eileen Draycott had therefore been working at the Manchester Rep since around 1926 (though in other theatres probably from 1910). In the interview she draws attention to that fact that her role in Armitage Owen’s play is not that of a ‘character actress’ suggesting that she did not wish to be considered as having that kind of specialism. (12)

She was praised for her performance of Mrs Hardcastle in some of the earliest productions of Love on the Dole – ‘verbal bouquets must also go to Eileen Draycott’ wrote the Huddersfield Daily Examiner (20 November 1934, p.6), while The Stage said that ‘Mrs Hardcastle [was] excellently portrayed by Miss Eileen Draycott’ (1 March 1934, p. 12). She continued in the part in the early Vernon-Lever touring production. She did not play Mrs Hardcastle in the Garrick London production but was one of the very few members of the original Manchester Repertory cast to take up her role again in the Broadway production in 1936. She then went on to play the key part of Mrs Shuttleworth in Greenwood’s next play, his undoubtedly sole-authored Give Us This Day, an adaptation of his second novel, His Worship the Mayor. Again, she received many positive reviews; the Sheffield Independent felt that in the production at the Sheffield Empire she played ‘the part of the suffering wife dogged by poverty in characteristic style’ (6 October 1936, p.7), while the Bradford Observer thought that ‘an interesting conception of Mrs Shuttleworth comes from Eileen Draycott’ in a production at the Leeds Empire (24 November 1936, p.7).

Eileen Draycott continued acting, mainly in repertory companies, throughout the forties, fifties and sixties, and also appeared in a number of BBC television productions including Noel Coward’s This Happy Breed in 1952, and an adaptation of Bleak House in 1959 (see her IMDB entry: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1865010/ ). The Stage carried a notice on 28 March 1963 (p.32) that she would be one of a nucleus of players reopening the Alexandra Repertory Theatre in Birmingham, but sadly she was taken ill shortly before that date, and died later that year on 24 September. She had worked continuously till she was seventy years old, putting in fifty-three years years on the stage, and acting in dozens of plays, almost all in repertory, which she said she loved (see the Birmingham Daily Post, 19 March 1963, p.27 for the report of her illness and the Birmingham Daily Gazette 8 April 1953, p.3 for an interview about her long career).

12. Noel Morris (Sam Grundy)

Noel Morris (1900-1952) was a well-known repertory actor in his day, but is not well-remembered – he has little trace in current media sources and no Wikipedia page. The Stage published a concise obituary for him after his early death:

His many friends will be sorry to learn of the sudden death, on February 12, of Noel Morris, at the age of 53. One of his first London engagements was in Jack o’ Jingles, at the New [Theatre]. His last London appearance was in The Crime of Margaret Foley, at the Comedy [Theatre], in which his performance as the Irish pig-farmer was memorable. Much of his career was spent in repertory, of which he was a great champion. He was, at various times, with the Plymouth, Bristol. Manchester and York companies. He also broadcast on numerous occasions and was on his way home from a schools broadcast when he collapsed and was taken to Middlesex Hospital, where he died. He was a splendid actor, a first-class producer and a staunch friend, and the theatre will be the poorer for his untimely death (21 February 1952, p.13).

Jack O’ Jingles was a piece by Leon M. Lion (who as it happened later produced Walter Greenwood’s completion of a D.H. Lawrence play under the title My Son’s My Son in 1934) and Malcolm Cherry, first put on at the New Theatre in 1919 – however Noel Morris does not seem to have been part of the original cast. (13) He was also with Edward Blythe the author of a who-dunnit first produced in 1927: On the Night of the 22nd, produced at the Little Theatre, Gloucester. By 1932 he was running a (summer?) school called the West of England School Of Dramatic Art : ‘Principal: Mr. NOEL MORRIS. OPENING CLASSES IN DRAMATIC ART. ELOCUTION. MIME, FENCING [and] CLASSICAL DANCING’ (Western Morning News, 6 June 1932). Morris had been a member of the Plymouth Repertory Theatre since 1921 but left to joint the Manchester Repertory Theatre in August 1933, some six months before the company gave the premier of Love on the Dole (Western Morning News,18 July 1933, p. 5). The role of Sam Grundy was perhaps like a number of others Morris played in being a striking one though not one actually on stage for that much of the play. However, most reviews took relatively little notice of the character, though several certainly praise Noel Morris’s performance in passing: The Stage said that he, like others in the cast, gave an excellent portrait of Grundy (1 March 1934, p.12).

In March 1940 Morris was appointed as general manager of ‘a Northern Garrison Theatre’, according to a report in the Western Morning News (29 March 1940, p.2). I am slightly puzzled by the indefinite article, but several later newspaper articles between 1940 and 1942 refer to the theatre in the same terms though without specifying a location: perhaps specifying the location was thought unwise in wartime? (I think it may have been near Bradford, but so far my searches have not satisfactorily filled this gap). The theatre apparently seated a (military) audience of seven-hundred, and hosted a mixture of Army bands, the ATS Concert Party, and professional singers (information from the Bradford Observer 2 November 1942, p.3, and the Yorkshire Evening Post 16 January 1940, p. 6). This kind of repertoire is also reported from another Garrison Theatre (I think at Aldershot Camp) in a wartime memoir by Ada Cavadini:

The Garrison Theatre stands behind our cookhouse. The performances are changed weekly, but straight plays do no appeal to most of the soldiers, who prefer variety shows with chorus girls and comedians. An army band sometimes plays there on Sundays. These concerts please everyone, for they are made up of classical music during the first half and dance music during the second half (This Was the A.T.S., Dorothy Crisp & Co. Ltd, London, 1946, p. 66).

Presumably, being the general manager of a Garrison Theatre was a way for Noel Morris, then aged forty, to do his bit during the war.

By 1944, Morris seems to have returned to acting rather than theatre management. He was warmly praised for his performance in a thriller (whose author I have not yet identified) titled Third Party Risk at the New Connaught Theatre in Worthing in September 1944. The review also suggests he had a considerable reputation:

One part stands out above the rest, which typifies a Harley-street specialist, Sir David Layering, M.D., F.R.C.P., in the throes of a possible triangular dilemma which, however, works out as the doctor ordered. John Wise as the doctor in the original production at St Martin’s Theatre. London, could have been no whit better than Noel Morris. whose polished performance reflected his usual careful study, deliberately professional, and exact, delightfully refined with a faultless diction that is rare nowadays and a pleasure to listen to (Worthing Gazette, 27 September 1944, p. 2)

Morris took a clearly striking but less major part in another thriller, The Crime of Margaret Foley, by Percy Robinson and Terence de Marney, which was first produced at the Theatre Royal Birmingham in April 1945. Reviews praised his portrayal of the Irish pig farmer who is murdered shortly into the play: ‘Noel Morris gives the warmth of brief life to the ill-fated pig-breeder’ (Birmingham Mail, 17 April 1945, p. 3). The Stage noted in 1947 that the play, still with Noel Morris in his original part, had come to the West End after ‘three years of provincial and suburban wanderings’ (17 July 1947, p.7). He played a number of roles and also directed plays in the later nineteen-forties. Though he did work on radio, he does not appear to have done any film or television work, which may be a large factor in why he has left little trace in the world of digital reference works, though many traces in the contemporary press.

13. Katherine Hynes (Mrs Dorbell)

I am unsure when Katherine Hynes began her acting career, but by the early nineteen thirties she was appearing very regularly in BBC radio drama of various kinds on the National Programme, with listings in newspapers including her name pretty much every week between at least 1930 and 1936. Quite often she appeared in what sound like ‘light entertainment’ pieces, such as this one:

Specially written for broadcasting by L. du Garde Peach, a multi scenic extravaganza entitled The Path of Glory, will be produced by Howard Rose . . . A large cast Include Gladys Young, Drelincourt Odlum, Andrew Churchman, George Manship, A. Brandon-Cremer, Floy Penrhyn, Philip Wade, Josephine Shand and Katherine Hynes (Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, 16 January 1931, p. 5).

L. Du Garde Peach was a playwright who began working in radio drama early in its history and remained very committed to it (for an introduction to his work see his Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L._du_Garde_Peach). In the same period Hynes also took substantial parts in Repertory productions as well; for example she played Celia in the Huddersfield Repertory Theatre’s fiftieth anniversary production of As You Like It in 1931 (The Era, April 1934, p. 16) and a significant part in a political farce, Important People by F. Wyndham-Mallock, at the Hastings Pier Theatre in 1933 (Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 8 April, 1933, p.5). She was also an active contributor to a group working to ensure the continued life of the Manchester Repertory Theatre on a sound financial footing, as reported in The Stage in 1935: ‘They announce that half the required capital has already been subscribed outside the city, and an opportunity of subscribing the remainder is presumptively to be given to local sympathisers’ (6 December 1934, p.12). Hynes’ performance as Mrs Dorbell in the first performance was generally admired if sometimes in odd terms and often jointly with the other two actors forming the so-called ‘chorus’: ‘Olga Murgatroyd, Katherine Hynes and Beatrice Varley played the three slatterns with broad enjoyment’ (the Manchester Evening News, 27 February 1934, p. 9). She did not, however, join the touring production nor the production at the Garrick, London.

She did though continue working in a number of Repertory companies throughout the thirties, taking a wide variety of parts, and many not the character actor type associated with Mrs Dorbell. The Leeds Mercury reported that Hynes married a well-known BBC sound engineer and announcer (said to have an ‘excellent microphone voice’), Roy de Groot, in 1936 – she had first met him while contributing to a topical piece on St Swithin and St Swithin’s Day, recorded at the BBC’s studios in Leeds (report 25 July 1936, p.10). After 1936 I have found no further traces of Hynes (nor a Katherine de Groot) and her BBC radio performances seem to stop, and as in a previous case, I assume that contemporary expectations about marriage, and perhaps also parenthood, had an impact on her career.

14. Alex Grandison (Harry Hardcastle)

Alex Grandison (1909-1983) has also not left a large footprint on digital media sources at least. He does have a IMDB entry, but it is thin as could be – it associates him with only one work – the pre-war BBC television production of J.B. Priestley’s play When We are Married (1938). He played Fred Dyson, which looks like a relatively small role. Nevertheless, as with all these early BBC TV broadcasts, he was contributing to a new and exciting form of media, in company with in this case the film director Basil Dean, and also the actor George Carney, playing the male lead of Mr Ormanroyd, and who three years later was cast as Mr Hardcastle in the film of Love of the Dole (released 1941). (14) Grandison anyway also left some larger footprints in the contemporary press, which can be traced through the invaluable British Library Newspaper Archive database.

Grandison seems to have started his career with the Manchester Repertory Theatre, appearing together with Edmond W. Waddy and Jean Winstanley in plays including the comedy It Pays to Advertise in 1933 (The Stage, 27 July 1933, p.4). Since Grandison was twenty-five years old in 1934, he was a reasonable if not perfect match for the teenage role of Harry Hardcastle in the premiere of Love on the Dole in February of that year. He was often praised as part of a good ensemble in early reviews of the play, but was also singled out for specific commendation as in the review of the touring production at the Huddersfield Palace: ‘Alex Grandison as Harry Hardcastle is another fine piece of acting’ (Huddersfield Daily Examiner, 20 November 1934, p.6). Grandison was one of the few Manchester Rep actors who was also in the cast of the Garrick Theatre London production (1935 to 1936). In a long and thoughtful review of this production The Tatler thought that ‘Alex Grandison conveys to the life the son’s loutish, pathetic adolescence’ (20 February 1935, p. 23). I am not sure that the part is always played as ‘loutish’ (not for example in the 1941 film, where Harry is plainly very sensitive?), but that could be an aspect of Harry trying to play the part of a man at the age of sixteen and under difficult financial circumstances (how can he be a man, with no suit and still in a boy’s clothes?). The Hull Daily Mail saw his performance in the production at the Hull Tivoli rather differently, seeing Harry performed as a ‘patient and then distraught son’ (10 July 1934, p.7).

After the long run of the Garrick and then Winter Garden production, Grandison moved back to Rep at the Coventry Repertory Theatre, appearing in a minor part in Do You Remember? in March 1937 (The Stage, 27 March 1937, p.11) and then a month later in Ian Hay’s Housemaster (first performed in London in 1936) and ‘doing good work’ as the character Travers (The Stage, 22 April 1937, p.7). He continued to appear at the Coventry Rep during 1937, but by October 1938 was appearing in a larger role (with Beatrice Varley) in J.B. Priestley’s play When We Are Married at St Martin’s Theatre, London, perhaps leading to his BBC TV role the following year. A review praised the cast’s Lancashire dialect and accents, and noted Grandison and Varley’s Manchester Rep background:

The London audience could hardly have realised the authenticity of the northern accents of the players. Everyone was proficient in the dialect. Two of them, Alex Grandison and Beatrice Varley, were, of course, at the Manchester Repertory Theatre. A number of the others, too. had north country theatre experience . . . When We are Married puts Priestley right where he ought to be – as the playwright of north-country people (Aberdeen Press and Journal, 12 October 1938, p. 6).

After that, I have not so far found much trace of Alex Grandison before the war. The distinguished theatre critic James Agate recalls him in his detailed review of the film of Love on the Dole in 1941, though in passing says that he seems to have had a low profile since 1935, and indeed warns Hibbert about the risk of disappearing from view after one much-praised role:

The best performance in the film comes from Geoffrey Hibbert as Sally’s younger brother . . . [which] is excellent, though not so moving as Alex Grandison’s in the stage-play. I have never heard of Grandison since, and I warn young Hibbert that, if he is to become a real film-actor, he will have to do a lot more than succeed in a part which plays itself. However, he has done very well for a beginning (The Tatler, 11 June 1941, p.6)

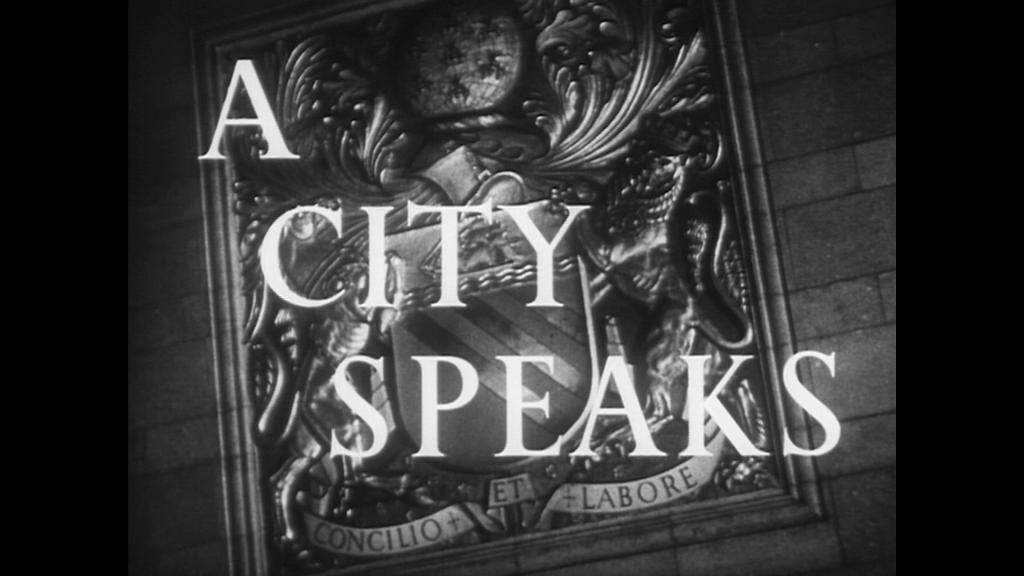

It may well be that Grandison, aged thirty, joined up or was called up in 1939 or 1940. He clearly did war service for he is recorded in 1945 in The Stage as among a number of ex-servicemen (in his case ex-army) who have joined the Theatre Reunion Association, an organisation dedicated to helping veterans resume their acting or theatre careers. (8 November 1945, p.8). The next trace I have found of him is as one of the ‘voices’ or voice-overs for the 1947 film A City Speaks – a Film about Local Government in England, a documentary about Manchester commissioned by the city corporation and focussing on its hopes for post-war reconstruction, which will put right both its nineteenth-century slums and war-time bomb damage.

The film was directed by the pioneering thirties documentary film-maker Paul Rotha, and had a screenplay jointly written by Ara Calder Marshall, Paul Rotha, and one Walter Greenwood. Grandison is credited as one of three named performers ‘among the voices’, the other two being Valentine Dyall (1908-1985) and Deryck Guyler (1914-1999). Both Dyall and Guyler had considerable and long careers including particularly as ‘voice’ and radio actors, as well as in film and television. It is noticeable that the ‘voice-overs’ in the film include some in a standard accent, usually speaking for the benefits of social progress and the material rebuilding of Manchester, and another in a Manchester accent with more immediate concerns, which often queries or doubts the value of local government and of the proposed plans, and also asks where the money will come from. Since Grandison came from Manchester and as we have seen was praised for his Lancastrian accent, and since neither Dyall nor Guyler were Lancastrians, it seems likely that these more grudging voice-overs are Grandisons! The assumptions about accent, class, education, intelligence and progressive thought built into this distribution of accents and attitudes are all too apparent. (15)

In the mid-fifties Grandison was working for BBC Radio as part of a unit called ‘Light Programme Presentation’, and in that capacity made a stage appearance at the Fortune Theatre, London in a play about psychiatry, popular fears, and medical ethics called Silver and Gold, by Warren Chetham-Strode. The production was apparently put on by the ‘BBC Club’. Grandison is reported as excelling as a ‘recovered patient’ (The Stage, 17 November 1955, p. 10). After that date, I have found no further traces of him.

15. Wendy Hiller (Sally Hardcastle)

Wendy Hiller (1912-2003) signed at the very bottom of the page. (16) She clearly contributed enormously to the Manchester Rep production of Love on the Dole, and it brought her instant star status, though paradoxically for portraying Sally as simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary. The Stage review praised many of the cast in what is largely an ensemble production, but did also praise Hiller as standing out individually:

In this role of Sally, Miss Wendy Hiller scores an undoubted success. Sally’s strength of character, independence, and indifference to ‘what they will say’ recalls, in some measure, the character of Fanny Hawthorne in that other Lancashire play, Hindle Wakes, though it takes a different form (1 March 1934, p. 12).

This does capture key elements in Sally’s character, and there is also much truth in the idea that in writing her Greenwood is likely influenced by Stanley Houghton’s Lancashire (and in fact Manchester School) play, Hindle Wakes (1912), and its highly independent mill girl Jenny Hawthorne. (17) The Tatler said of the Garrick production ‘the Sally by Wendy Hiller glows with tenderness and native strength’ (20 Feb 1935, p.23), while the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer praised the overall architecture of her performance in a paragraph headed ‘Miss Hiller’s Success:

Miss Wendy Hiller’s acting of Sally Hardcastle was beyond all praise . . . At first, she seemed over-simple, but there lay her subtlety. In all three acts her character shows consistent development to the final difficult, but defiant, decision (1 February 1935, p.3).

The Illustrated and Sporting Gazette simply reported of the Garrick performance that: ‘Wendy Hiller’s appearance was hailed after the first night “as the rise of a new star” ‘.

Hiller was honoured in 1935 (though the series title is dubious!) with this cigarette card. The text gives an accurate and concise account of her career so far, while the image shows her in the scene in Love on the Dole where she goes rambling on the moors with Larry Meath ((Act II, Scene 2). For further discussion of this artefact see: Love on the Dole: a Second Cigarette Card (1935).

Wendy Hiller began aged 18 with the Manchester Repertory Theatre as a ’student’ (a position which offered the chance to learn about many aspects of theatre while doing useful – if unpaid – work) in 1930. Her father was a Manchester mill owner, so could perhaps afford to help support her in her early theatre career. She played some small parts before becoming assistant stage manager in 1931. This was presumably a paid position, but she was in fact let go in that year presumably because the company could not afford her (it certainly some money problems in the early thirties), before being recalled a three years later to play Sally Hardcastle on the basis that she had a genuine Lancastrian accent (in fact the Manchester Evening News reported that it was a more formal and competitive process than that – she was among fifty others who answered a call to audition for the part, 15 February 1934, p.4 ). At some point George Bernard Shaw saw Love on the Dole and was impressed by Hiller in particular. He invited her to act in Pygmalion at the Malvern Festival in 1936, as well as in St Joan, and then chose her to play the part of Hilda Doolittle in Gabriel Pascal’s 1938 film of Pygmalion. Her performance was acclaimed and she became something of a Shaw specialist, playing the lead role also in the film of Major Barbara (directed by Gabriel Pascal, Gabriel Pascal Productions, 1941). From then on she was a film as well as theatre star.

She played Sally in Manchester, in London and in the New York production; she also, as observed above, married the play’s co-author, Ronald Gow in 1937. In an interview at the beginning of 1938 Hiller showed some reservations about being typecast in Sally-Hardcastle-like roles (whatever they might be?), but later the same year expressed considerable enthusiasm for taking on the same role in a film version. The Sunderland Daily Echo & Shipping Gazette, covering Pascal’s film of Pygmalion and his casting of Wendy Hiller, included an interview with Hiller which is worth quoting at some length for an unusual insight into some of Hiller’s feelings about the role of Sally Hardcastle:

‘Following’ Love the Dole, I did receive a number of rather tempting Hollywood offers, but I turned them all down for two reasons. First, I was not altogether sure that my stage success hadn’t come too quickly. Secondly, I felt I would rather stick to the theatre and later make my acquaintance with the cinema through British films. You see, so far as my future was concerned, I had to live up to my Love-on-the-Dole reputation, and at the same time had to live it down. I was afraid that if I went to Hollywood, I might be faced with the danger of being built up into a player who always features in the same kind of roles (22/1/1938, p.7).

However, Hiller seems to have felt more positive about Sally later in the year. The Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette film critic ‘Stargazer’ reported that Hiller ‘has an ambition’ to be involved in a film version of Love on the Dole and that he ‘has an inkling that it may be one of Pascal’s future productions’ (8/4/1938, p.20). In fact, despite continuing press interest in who might play Sally in a film version of Love on the Dole (see: https://waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com/walter-greenwood-and-gracie-fields/), Greenwood and Gow do not seem to have sent another proposal to make the film to the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) until 1940, and when Greenwood and the director John Baxter were casting the film that year, Hiller was not considered. However, she went on to a long and successful career in film and on stage, but always prioritising her theatre roles. When Hiller went to the US to play Sally in the Broadway production in 1936, this opened up opportunities for other actresses, two of whom, Ruth Dunning and Dorothea Rundle, also launched successful careers from their interpretations of Sally Hardcastle.

Though Hiller always preferred stage acting to movie acting, she nevertheless played numerous starring or cameo roles in films in every decade from the nineteen-thirties till the nineteen-eighties, appearing in some twenty films, as well as in a similar number of television roles from the sixties until the nineteen-nineties. She was made an OBE in 1971 and a DBE in 1975. Throughout her career she always also was acting in major theatre productions, mainly in London, but also in New York (see her Wikipedia entry for an overview of her career and listing of her main theatre, film and television roles: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wendy_Hiller).

16. Audrey Cameron (Stage Manager)

Finally, we come to Audrey Cameron herself – and firstly her signature which we have not yet seen.

The first thing to note about Audrey Cameron is that there were around this period several distinct Audrey Camerons at work in theatre and film, so we need to get the right one. In fact, only one has a birth-date which makes it possible for her to have been an adult in February 1934, and that is the Audrey Cameron who was born in 1908 (and died in 1982). Her obituary in The Scotsman records that she was born in London and educated in England and France, and first appeared on stage aged nine, before working in America for a period, and becoming ‘the first woman stage-manager [in Britain?] at the age of 22’. It then reports that when she returned to Britain, she ‘became a producer in the BBC radio department’ and was made an MBE in 1966.

To this concise overview we can add considerable further detail from press reports about her throughout her life. An earlier Scotsman article tells us that she acted with Ellen Terry aged ten in a production of The Merry Wives of Windsor and that having retired from the BBC in 1966 she in fact returned to the stage, and was in 1968 playing ‘the Barge Woman’ in a production of Toad of Toad Hall at the Lyceum (though I am not sure which Lyceum). The article reports that: ‘Audrey Cameron’s dearest wish would be to go on acting “until I drop”, if she can only get the chance’ (4 January 1968, p.6). The London Daily Chronicle reported in 1930 that she had first acted as an assistant stage manager at the Everyman theatre when she was seventeen in 1922, and that she was still being asked both to stage-manage and act aged twenty-five: ‘ “Oh Audrey will do that” was always ringing in my ears’ (6 February, p. 13). This certainly sounds to modern ears potentially exploitative, but perhaps paid off in the end in her long and successful career as a producer. The play in question was (ironically?) a play about work called Nine Till Six (by Aimee and Philip Stuart), and drew considerable publicity because of its all woman cast and production team, including Cameron as stage-manager (Norwood News, 16 May 1930, p. 21). Though Cameron spent much of her career as a then rare female radio producer, it is clear that actually she continued with her dual roles, since she is frequently listed as an actor in radio drama from the thirties on until the sixties.

Conclusion

I assume that for all the actors appearing in the first night of Love on the Dole it was to an extent business as usual – good to be working rather than resting, good to have the excitement of a first night in a new play. However, Audrey Cameron at least clearly thought it was a rather special first night – worth bringing in her copy of the novel of Love on the Dole, or even worth buying a copy (though of course I would like to believe that she had already bought it and read it!), and worth getting all the named cast members, the producer and the two co-authors to sign it. For most of the cast the Manchester Repertory run of this play was as brief as that of most of the company’s plays. Indeed many had played in the previous Manchester Rep productions and immediately played in further ones – short runs were part of the economy and life of Repertory companies because they had to bring the essentially local audience into the same theatre again and again over the course of a year. However, for a few of the first night cast Love on the Dole provided a long run of employment: Wendy Hiller, Alex Grandison, Beatrice Varley, Edmond W. Waddy and the mysterious Leonard Hart (newsboy) all joined the ‘ first provincial tour’ of the play, which started in May 1934, at the Theatre Royal Hanley. Four of these actors – Hiller, Grandison, Varley and Waddy – in turn were also cast in the London Garrick production which opened in January 1935 and ran until January 1936. Just two – Hiller and Grandison – then transferred to the New York production at the Shubert Theatre, which ran from February to June 1936. So, for most of the cast, Love on the Dole was one engagement among many, but for a few it was a transformational event. Edmond W. Waddy remembering in her obituary his wife of 45 years, Beatrice Varley, was clear that it was the play which made her name, despite her already long acting career. Grandison was praised for his role in the play, and yet never quite made it big in any other part. For Wendy Hiller the play was her launch-pad to stardom in several simultaneous ways – her performance as Sally Hardcastle was reported to be phenomenal in practically every newspaper in Britain, and George Bernard Shaw’s appreciation of her acting (though he did not care for the play) took her to highly praised Shavian film parts (see George Bernard Shaw, Wendy Hiller, and Walter Greenwood). Her marriage with the co-author Ronald Gow in 1937 was also of some importance for their joint careers which often drew on their creative partnership.

However, if Wendy Hiller was the evident star to emerge from Love on the Dole, many others in the cast also went on to (or continued with) life-long careers in which they were in constant demand, many in repertory theatre, but many also making contributions to the newer media of radio, film and television. The biographies above suggest how theatre careers spanned these new media as well, and indeed how central the repertory companies were to both the regional and national theatrical economy of Britain in the interwar period. Indeed, Love on the Dole‘s relationship to repertory theatre seems to have been key both to its dramatic character and its success. The play’s aesthetics had roots in the Manchester School of realist regional theatre which in turn had its roots in the repertory theatre movement, which began, of course, in Manchester itself. As we have seen, Hindle Wakes may have been an influence on Love on the Dole, and we know from Greenwood’s memoir that the Manchester School playwright Harold Brighouse was a writer he regarded as a model – while unemployed and writing Greenwood ritually walked every day in the hope of success past Chapel Street, ‘one of whose bow-fronted shops was reputed to be the original around which Harold Brighouse had written his famous play Hobson’s Choice‘ (There Was a Time, 1967, p.224). Greenwood must have been delighted when Harold Brighouse himself positively reviewed the novel for the Manchester Guardian on 30 June 1933- a review which was quoted in an extract on the first edition dust-wrapper rear inside flap:

One of the aims of repertory theatre was to produce local plays with appeal to a local audience, and Love on the Dole met that criterion, but as the reviews made clear the play also addressed a national problem of sustained unemployment and poverty in a way which theatre audiences all over Britain and from all social classes could understand and empathise with. In fact, it seems to me that without its repertory theatre start and instant fame across major national newspapers, it is unlikely Love on the Dole would ever have made it to a London theatre and the national theatrical success which played a very large part in launching both Greenwood and Gow on sustainable writing careers.

NOTES

Note 1. The first production of this dated back to 1914, but it was extensively revised for a 1924 production as the first of twelve ‘Aldwych farces’ at the Aldwych Theatre London (the remaining eleven farces were all by Ben Travers). See the Wikipedia entry on the play: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/It_Pays_to_Advertise_(play).

Note 2. For an introduction to the play see its Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escape_(play) .

Note 3. For introductions to these two plays see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Private_Lives and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laburnum_Grove_(play) .

Note 4. This was a musical which stemmed from a 1919 song of the same title. The music and lyrics were by Arthur A. Penn. The play was written by Jane Cowl and Jane Murfin and first performed on Broadway in 1919, registering as a distinct hit. There were then film adaptations in 1922, 1932 and 1941. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smilin%27_Through_(play).

Note 5. See: https://rarefilmm.com/2021/10/said-oreilly-to-mcnab-1937/ .

Note 6. For Clifford Marle’s silent film work see: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1183081/ . Though IMDB gives his date of death as 1935, he was praised for his role in the premiere of George Bernard Shaw’s play On the Rocks by the Birmingham Daily Gazette on 16 March 1936, p.3 and as noted in the main text had newly joined Birmingham Repertory Theatre at the end of March 1936. I have not found any further reference to him after that date, nor as yet an obituary.