When the novel, then the play and after a six-year pause the film of Love on the Dole appeared between 1933 and 1941, there were hundreds of positive reviews in the press in both national and regional newspapers. These took a variety of positions on why it was a valuable work, with probably the majority of reviewers of novel and play highlighting its immediate impact in the contemporary context of mass unemployment and the resulting widespread poverty (the film was seen slightly differently against a combined thirties and forties background). However, there were also those who predicted longer-term kinds of value and consequent longevity for Greenwood (and Gow’s) creative work. This article will look at fourteen varied and striking examples of how Love on the Dole in the short term and in the longer term was seen as a uniquely valuable work. The following short quotations (‘headlines’ in effect if not fact) are mainly taken from press reviews and give an overview of the intimations of immortality (or in some cases mortality) felt by reviewers. Each of the quotations immediately below will be quoted a little more fully and then discussed in more detail further on in the piece, when their authors and full sources will also be given.

‘It would be interesting a hundred years hence to hear what students of twentieth-century England have to say about such a book as Love on the Dole . . . As a novel it stands very high, but it is its qualities as a “social document” that its great value lies. Harry Hardcastle and his wife Helen are typical of thousands of their contemporaries and so is Sal Hardcastle and her fated lover, Larry. They all have the tragic gift of vision which makes them loathe the slum in which they exist; they all have the tragic craving for beauty which brings Larry to his death and Sal to humiliation. Harry’s passionate desire to create which made him. at fourteen, throw aside his safe but sordid job as a clerk in a pawnshop for the giant engineering works is killed cruelly and inevitably as he realises he is merely a tiny cog in a soulless machine, which turns him and thousands like him on to the streets at the age of twenty-one with practically no further chance of employment . . . Mr Greenwood gives us a terrible picture of people caught in a trap, helpless and hopeless. (1933). (Quotation 1)

‘The book I liked best since the war is Love on the Dole . . . It has every possible merit that a novel can have . . . It is packed with eagerly living characters. It tells a good story swiftly in clean and cutting English. But the most important thing about it is its passion . . . [about] the appalling conditions in which millions of English men and women are now living’ (1933). (Quotation 2)

‘There is not in this play that imaginative impact which reveals a new world – a world seen first by the artist alone and revealed and universalised by him; it is not, therefore, in the highest sense, an originating work of art, and cannot well endure beyond its occasion; but, being conceived in suffering and written in blood, it profoundly moves its audience in January 1935. (Quotation 3)

Frequently have I sat and listened, with dozens of fellow-Southerners, to speakers attempting to convey something of the conditions which they know to exist in the industrial areas of the country. If the speaker has been a good one he may have been able to convey a fleeting glimpse of the distress in those area – but it is a glimpse which lasts, perhaps, until we return to our comfortable fireside, or perhaps only until we reach the fresh suburban air outside. What do we in the South know of the conditions that actually exist in our country? Little, I fear, or nothing. It takes far more than speakers and writers to convince us that something may be rotten in the state of Denmark – it does in fact require a dramatist . . . [Love on the Dole] is an opportunity to see and understand which should not be missed and certainly not one to be regretted. (Quotation 4)

‘England is to-day comparatively prosperous . . . Would the play stand the test of changed conditions ? Was it a play of one moment only? Would it date? Doubts soon disappeared, the play stood the test of altered conditions splendidly’ (1937). (Quotation 5)

‘Of all contemporary plays possessing claims to immortality none is more certain to be seen by our grandchildren and by their grandchildren than Love on the Dole‘ (1935). (Quotation 6)

‘The play will be useful to future historians, who are in search of an unbiased account of the conditions under which people of Great Britain lived in the 30’s’ (1938). (Quotation 7)

‘Love on the Dole is a picture you will never forget . . . It’s a British Grapes of Wrath. There are no great stars, but there are some fine performances. And they make one of the most tremendous true-to-life stories of the century, a picture that grips everyone who sees it’ (1941). (Quotation 8)

‘A drama of the evil days that followed the last war and a warning and a plea that such conditions should never happen again in the new Britain. British National have made a brilliant adaptation of the successful play Love the Dole’. (Quotation 9)

‘I wrote a book you may remember. It was called Love on the Dole. Then it became a play. Now it’s become a film. In every guise Love on the Dole was intended to point to the kind of Britain we don’t want after this war. A Britain of unemployment, misery, repression and injustice. This book was intended to be the harbinger of a New Britain’ (1941). (Quotation 10)

‘It holds enormous promise for the future. If every man and woman in Britain could see this film. I don’t think we would ever go back to those dreadful pre-war years when two million men and women were allowed to rot in idleness. I don’t think the censors meant us to feel that way about it, but Walter Greenwood did. He succeeds magnificently. So, I beg you, please, please go. It is flawless. and it will win world fame (1941). (Quotation 11)

‘Much of the emotional torment poured into Walter Greenwood’s novel, Love on the Dole . . . seemed outdated and quite incapable of triggering off any warnings about the misery and indignity of being out of work. Frankly, I doubt if people want to know about or be reminded of the bad old days’ (1967). (Quotation 12).

‘A man of the people who entertains all sorts and conditions and appeals instantly and directly to their hearts . . . the paradox and fascination of [Love on the Dole] is that although the situation gave Walter Greenwood a pen of fire it is his approach to fiction that makes his work a classic’ (1971). (Quotation 13)

‘[Love on the Dole] enjoys a unique place in the British repertory as an expression of the working-class social conscience which has enjoyed lasting favour with the bourgeois public’ (1980). (Quotation 14)

Quotation 1.

The TLS (Times Literary Supplement) novel review was published on 29 June 1933. It was written by a regular reviewer, Mrs D.L. Murray (1889-1960), also known professionally as Leonora Eyles, a feminist, socialist and novelist, who reviewed both novels and sociological works (for an introduction to her extraordinary life and career see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonora_Eyles ). The review was unusual in projecting the importance of the novel as historical testimony a century into the future and wondering what the book would have to say to students of the history (rather than literature) of twentieth-century England. This suggested both that the importance of the novel was essentially as a document of social conditions, while also showing faith that the literary work would still be being read (and would stay in print?) till at least 2033. Indeed, the review does also praise the text’s achievement as a novel and gives a moving account of the tragedy in which all its working-class characters are caught up – with aspirations either high or simply ordinary, but all bound to be thwarted. Up to 2024, the prediction of a hundred-year life for the work (as both literary text and historical document) looks on course – the novel is in print and is still being quite widely read, as far as one can tell.

Quotation 2.

This was by the novelist Beverley Nichols (1898-1903), a prolific and very successful novelist, playwright, garden-writer and journalist. It was part of an article published in the Sunday Times on 12 November 1933 (p.iii) titled ‘Books I Have Liked Best Since the War – a Symposium’, and asked five writers for their choices and views. He names several other popular novels, but is certain that Love on the Dole ‘is a finer novel than any of these best-sellers’. though he also notes that ‘comparatively few people seem to have heard of it’. The novelistic ‘merits’ he names at the start of the quotation given above suggest that for him it is both the literary qualities and its core topics which make Greenwood’s novel unique. However, he does reinforce its contemporary significance in his final section on Love on the Dole:

It introduces us to an underworld of which every ‘patriot’ should heartily ashamed. And if its reading were made compulsory for every member of Parliament, there would be no chance of voting for increased Army Estimates while so many millions of decent citizens were forced to lead the lives of caged beasts.

This comment of course predates Herbert Samuel’s advice to MPs in March 1935 that they should all see the play version of Love on the Dole if they really wished to understand what the unemployment figures meant, but clearly shares with it the view that the work showed the truth and mediated it authentically enough to motivate political action and adjust political priorities (though hindsight might modify somewhat the question of Army Estimates in 1933). Nichols’ view is very much a balanced one – content, topicality, and aesthetics combine to make Love on the Dole outstanding over the period from 1918 to the present of 1933.

Quotation 3.

The Times published a review of the London production of the play which was highly positive about its contemporary insights, but which starts by explicitly asserting that it was not an original work of art and that it could not outlive its ‘occasion’:

There is not in this play that imaginative impact which reveals a new world – a world seen first by the artist alone and revealed and universalised by him; it is not, therefore, in the highest sense, an originating work of art, and cannot well endure beyond its occasion; but, being conceived in suffering and written in blood, it profoundly moves its audience in January 1935. Its scene is an industrial town; its subject unemployment; and it has the supreme virtue in a piece of this kind of saying what it has to say in plain narrative, stripped of oration (‘ Garrick Theatre’, 31 January 1935, p.12).

Clearly here art is firmly associated with originality and the creation or discovery of new worlds through a unique artistic vision which can nevertheless be shared. Love on the Dole is seen quite reasonably as doing something different in revealing a world which already exists, though it will be new to most audiences. The play draws on experiences all too actual and presents these powerfully by using simple narrative tools and shunning speechifying and political rhetoric. It speaks to the social crisis in progress since 1929, and once that has receded into the past the play’s work will be completed. The play is wholly adapted to its purpose in the present, but will have no future since it is not an autonomous work of art but dependent on its historical context. Nevertheless, given its immediate focus, its literary means are appropriate and maintain a concentration on the actual rather than on political representation of the actual (the word propaganda seems just under the surface here for the writer): ‘plain narrative, stripped of oration’.

Quotation 4.

A regional review in the southern newspaper the Uxbridge & West Drayton Gazette is equally eloquent and broadly representative too of responses focussed on the play’s bearing witness to a current crisis. However, unlike The Times, it saw the role of artistry in the form of drama as a key part of Love on the Dole‘s contemporary impact:

NOT TO BE MISSED THE PLAY WHICH DARES TO BE VITAL

Frequently have I sat and listened, with dozens of fellow-Southerners, to speakers attempting to convey something of the conditions which they know to exist in the industrial areas of the country. If the speaker has been a good one he may have been able to convey a fleeting glimpse of the distress in those area – but it is a glimpse which lasts, perhaps, until we return to our comfortable fireside, or perhaps only until we reach the fresh suburban air outside. What do we in the South know of the conditions that actually exist in our country? Little, I fear, or nothing. It takes far more than speakers and writers to convince us that something may be rotten in the state of Denmark – it does in fact require a dramatist.

To all those who have the slightest interest in current affairs, I can with all sincerity commend the play by Ronald Gow from Walter Greenwood’s novel, Love on the Dole. The management of the Garrick Theatre have been courageous in bringing such a vivid picture of Lancashire life to laughter-loving London, but their spirit should be rewarded. The play gives Londoners an opportunity to see the tragedy – and fortunately some of the humour – of the life in the industrial areas. It is an opportunity to see and understand which should not be missed and certainly not one to be regretted (by S.R.C., 15 February 1935, p. 13).

This lays much more emphasis on the difficulty of making audiences really engage with worlds which are actual but outside their experience. Notably here, as in many other reviews, southern audiences and audience members are firmly assumed to be comfortably-off (each with a ‘comfortable fireside’ and ‘the fresh suburban air’), as if everyone living south of Watford were middle-class or above. This imagined audience also seemed to this reviewer not too prone to sustained analysis from their comfortable armchair viewpoint. Lecturers and journalists and witnesses have difficulty breaking through this comfort zone, and that is why the drama animating Greenwood and Gow’s Love on the Dole‘s vision is essential. The review is pretty clear the play is about a structural problem with the ‘state’ of Britain, and enlists Shakespeare in that suggestion. It also praises the courage of putting on such a play in London and breaking into the comforting current theatrical preferences of ‘laughter-loving London’ with something much more real.

Quotation 5.

However, some reviews also predicted a longer-term significance for the play, though within a variety of time-frames. The Birmingham Daily Gazette in its 1937 review of a repertory production at the Alexandra Theatre in one way emphasised the play as being tied to a very short and particular period, but then also saw it as being successful beyond that context:

TIME HAS NOT DIMMED ITS APPEAL

Love on the Dole was a great success when it was first produced in 1934. There was nothing surprising in that. It is a play pulsating with humanity and packed full of things that are real, ugly things, beautiful things, things that hurt and things that amuse, but all real things, the stuff of which life is made; and the appeal of the play is to both mind and heart.

DOUBTS DISAPPEAR

The depression of 1930 and subsequent years was still having its psychological effect on the minds of everyone in the country. The circumstances in which the Alexandra Theatre repertory company presented the play last night, however, were very different. England is to-day comparatively prosperous and Birmingham is one of the principal centres of its prosperity. Would the play stand the test of changed conditions ? Was it a play of one moment only? Would it date? Doubts soon disappeared, the play stood the test of altered conditions splendidly. It has lost none of its appeal. And the company stood the test of a difficult play equally well (16 November 1937, p.3). (Q6)

This asks the question whether Gow and Greenwood’s play could survive long beyond its original social and economic context in the unemployment crisis between 1930 and 1935, when its ‘topicality’ as well as its contents made it a ‘great success’. The reviewer feels that the play has survived on its own merits in this Birmingham production even though by 1937 ‘England is today comparatively prosperous and Birmingham is one of the principal centres of prosperity’. Of course, it was one of the features of the Depression in Britain that its effects were regionalised, with the worst unemployment being most enduring in the nineteenth-century heartlands of heavy industry, including parts of Scotland, Wales and northern England, while parts of the Midlands did indeed have something of a boom in the second half of the thirties, with the impact of an emerging consumer culture (photography, gramophones, cinema, cheaper cars) for those in steady employment, as well as the gradual impact on industry of rearmament after 1935. In other areas there was relatively little improvement in long-term unemployment and poverty until nearer the end of the decade. The review does not pursue very far the question of what still appealed to a Birmingham audience in 1937, but simply remarks that they respond well to the play itself.

Quotation 6.

The Croydon Times reviewer of a 1938 production took a considerably longer view. While seeing the contemporary witness of the play sharply, they also predicted that it would remain in the canon of performed British drama for generations:

Love on the Dole. A Play To See, To Think About, And To Talk About.

Of all contemporary plays possessing claims to immortality none is more certain to be seen by our grandchildren and by their grandchildren than Love On The Dole. Ronald Gow’s brilliant dramatisation of Walter Greenwood’s famous novel is the attraction at Streatham Hill Theatre this week. It has been seen by millions of people in this country and abroad: millions will continue to see it as long as sympathy for the distressed and compassion for the despairing remain characteristics of the human race.

With the theatre passing through a phase in which light, frothy comedies, often unrelated to reality predominate, it is refreshing and sobering to come face to face with a play which exposes nakedly what passes for life and love in the distressed areas. Frustrated hope marches side by side with unremitting hardship for the common folk of Hankey Park; their lot is hard while the men have the privilege of belonging to the dark army of wage-slaves. It is infinitely harder when they belong to the infinitely darker army of the unemployed. The play reveals the hopes and the ideals, the terrors and the temptations that go to make up the gloomy lives of these pitiably poor people. It paints with deadly effect the picture of the disintegration of family life. The most diehard believer In the efficacy of the present system of society could not sit through it without experiencing an uncomfortable urge of conscience to revise his standard of values. It is a play to see, to think about and to talk about. Leslie Latimer’s production bears the hallmark of authenticity, and the play is a triumph of teamwork. Every part is played for all it is worth by a cast which seems to believe in the message of the play (22 October 1938, p. 14).

The reviewer acutely picks out some of the central themes in the play, which shows how in Hanky Park ‘frustrated hope marches side by side with unremitting hardship’, and how working people there are always on the brink of poverty, and how the Depression has tipped most over that edge leading to ‘the disintegration of family life’. Like the Uxbridge & Drayton Gazette review it also relates the play to the contemporary theatre context: ‘light, frothy comedies, often unrelated to reality predominate’. Instead Love on the Dole ‘exposes nakedly what passes for life and love in the distressed areas’. There is a focus here on the current context, but the review does make precisely a claim that this play is an autonomous work of art which will long survive this specific context in which it has been made: ‘millions will continue to see it as long as sympathy for the distressed and compassion for the despairing remain characteristics of the human race’.

Quotation 7.

Another review, in the Norwood News and, as it happens of the same production, equally sees the play as contemporary witness, but predicts a longevity based not so much in artistic but in retrospective historical significance:

Love on the Dole, one of the finest plays written in our time, comes to Streatham Hill Theatre next Monday, with several members of the original cast. The play is a classic, giving an unforgettable picture of life during the present day, with its many vital social problems. It is so near to all of us that it has had a tremendously wide public appeal, having been performed with enormous success in all parts of the country, and in America, where, on the first night the audience rose as one man and cheered the production to the echo . . . The scenes abound in comedy, yet deal in a really sincere manner with the modern problem of unemployment. The characters are real hard-working people who are caught in the throes of depression, and instinctively one feels that these brilliant young authors have told the truth in this compelling a social drama. The play will be useful to future historians, who are in search of an unbiased account of the conditions under which people of Great Britain lived in the 30’s and they will not fail to realise that the magnificent English sense of humour played a vital part in seeing them through (Norwood News, 14 October 1938, p.13).

Unlike the Birmingham Daily Gazette review, this account from Norwood in London does not see the period between 1933 and 1935 as being by now remote, but regards the play as still about the present, even though at the same time it suggests a degree of historical retrospective through its phasing: ‘an unforgettable picture of life during the present day’. There is thus a certain temporal ambiguity in the review – it is about an experience ‘so near to us that it has had a tremendously wide public appeal’ but also sees this present becoming history for ‘future historians’. The review’s statement that the play is ‘an unbiased account’ rather simplifies the extent to which Greenwood and Gow’s creation does have, despite the view of The Times to the contrary, its own vision of the effects of long-term unemployment. Perhaps most curious though is the review’s final sentence which transposes an effect which one might think is theatrical and a matter of genre to the actual experience of the depression – and indeed sees it as a national saving grace: ‘[that] magnificent English sense of humour ]which] played a vital part in seeing them through’ (for a discussion of humour about unemployment and the dole see Doleful Humour: Laughing Off Unemployment Between the Wars? * ).

Quotation 8.

Given that the BBFC (British Board of Film Censors) prevented production of a film version of Love on the Dole until the second half of 1940 (blocking it in 1935 and 1936, and indeed again in the early part of 1940), the film was finally released in a very different context from both novel and play. Indeed, the British film release on 28 June 1941 meant that it was a text made available to the public eight years after the novel, and six years after the play version. Between 1933, 1934-5 and 1941, the historical and social situation of Britain had seen enormous changes, from mass unemployment to a man and womanpower shortage as the wartime economy demanded all the labour which could be supplied. Public perceptions had also undergone sharp changes, with a generally-felt sense of national purpose and a more-or-less patient acceptance under these circumstances of the necessity of state intervention in nearly all aspects of life, including the introduction of an essentially command economy. This meant that reviews of the film of Love on the Dole mainly adopted a historical perspective on a film set in the thirties, but which also showed a clear sense of its wartime viewing context, and its likely impact on the future of Britain. Thus most reviews of the film centred on its visions of past, present and future.

The Worthing Gazette was a slight exception to this trend, however. With only implicit comment on the social context of the original story and the wartime context on which the film was made and first viewed, it focussed instead on artistic merit and lasting value. First it saw Love on the Dole as of equal artistic worth with The Grapes of Wrath (directed by John Ford and based on John Steinbeck’s novel of the same name, 1940), a US film hailed as a great work of art though also, of course, as profound social comment on the Depression. Then it asserted both the greatness of the film’s story in the context of a century, before stating the similar greatness of Greenwood’s original novel, its universal audience appeal, and indeed the need for everyone to read the book and see the film (the play gets no mention!).

Love on the Dole is a picture you will never forget . . . It’s a British Grapes of Wrath. There are no great stars. But there are some fine performances. And they make one of the most tremendous true-to-life stories of the century a picture that grips everyone who has seen it. Everyone who has read Walter Greenwood’s world-famous novel will want to see it on the screen – and everyone who hasn’t read the book will want to see it too (3 September 1941, p.2).

It may well be that the social value of the film is implicitly assumed here throughout, but aesthetics dominate the surface of the review. In most of the wartime reviews, social and historical contexts are the more dominant frames. Most typical were responses which located the value of the film in its commentaries on the relationship between the depressed thirties, the wartime forties, and the hoped-for post-war new beginning.

Quotation 9.

Kinematograph Weekly was, of course, a publication aimed mainly at keeping cinema professionals, including picture-house managers, up to date with current and upcoming productions, but this task also included sharp reviews of completed films with views on what kinds of audience they might appeal to, as well as comments on flaws which might deter some viewers. It was not in general a particularly political periodical, but one notes in its first brief review of the film of Love on the Dole that it takes for granted a widely shared set of relatively new political beliefs:

A drama of the evil days that followed the last war and a warning and a plea that such conditions should never happen again in the new Britain. British National have made a brilliant adaptation of the successful play Love the Dole’ (Kinematograph Weekly, 27 March 1941, p. 19).

This takes as a given that the post First World War British economy was badly and presumably avoidably mismanaged (something of course easier to be wise about after the event) by the post-war governments: Conservative, Labour, National in turn (strictly Churchill’s then current wartime coalition was still the successor to the National Government re-elected in 1935). The statement implicitly supports a managed economy with state intervention and post-Second World War national planning to bring that about, with the goal of never returning to the sustained unemployment, miserable poverty, and industrial decline of the thirties. This is a good deal of freight for Greenwood and Baxter’s film to carry, but this was how it was both at least partly intended and widely understood, as the next two quotations will also show.

Quotation 10.

The next quotation is an exception in that it is not a quotation from a review, but rather from a quite substantial statement made to (or perhaps better for) a newspaper during 1941 by Greenwood and articulating his own understanding of the value and signifiance of Love on the Dole (novel, play and film). The statement, with a prominent headline and eye-catching typography, was published in two sister Sundays with broadly popular Labour sympathies. It probably therefore reached quite a large and sympathetic audience, especially since it was closely integrated with the film which was currently proving both a critical and cinema success. A box in the centre of the piece drew attention to the author and then handed over to the equally striking headline at the top of the article:

WALTER GREENWOOD wrote the book from which the film Love on the Dole was made. Now let the author tell you what the picture means to the New Britain.

And We Must Win the Peace

LOOKING past the war which is really nothing I more than a ripple on the surface of the sea of mankind’s history, I feel that we are on the threshold of a bright new world. On the threshold of a future which will please only honest men, the men who look to this war to produce a better and finer civilisation for the human race. But when we have won the war, we must see to it that we are not stupid enough to lose the peace, or the vision that we now have of the New Britain will be lost for ever.

For some people, of course, there will be defeat whatever happens to the conflict between Germany and ourselves. But the defeat will not be of Britain, as we want it to be, of Britain as we have always dreamed it ought to be. The losses will be borne by a Britain which must be defeated anyhow, by the Britain of the counterfeit cheapjack, the element which has lived on the success of the most prosperous Victorian generation. It is up to us to see that this war means complete defeat for the cheapjacks of Britain, to see that even when right triumphs, wrong, as represented by them, must be defeated. And we don’t really need the Nazis to help us to win this victory. We could have beaten this enemy long ago if we’d gone to war against him with the same spirit in which we now fight Hitler.

I wrote a book, you may remember. It was called Love on the Dole. Then it became a play. Now it’s become a film. In every guise, Love on the Dole was intended to point to the kind of Britain we don’t want after this war. A Britain of unemployment, misery, repression and injustice. This book was intended to be the harbinger of a New Britain.

Let us fight and beat Hitler by all means. But while we’re doing it, let us bear in mind these other enemies. For they are just as big a threat to democracy and decent living and to happiness as the Panzer Division of the German Army WE MUST BEAT THE ENEMIES AT HOME AS WELL AS ABROAD.

Let’s call out a home guard against the social evils which existed – they will exist again unless we stop them – at the time I wrote my book. Otherwise, we might as well lose that war to Germany.

At the moment we have a new morality. A new sense of social responsibility. ‘Never again must we have the evils of unemployment, of undernutrition, of social injustice’, says the nation.

Fine, I’m glad to hear it. But it’s a great pity it takes a war to make us say it. A still greater pity if we forget these high ideals when the war is won, and slip back, gradually though surely, into the old evils.

It has always been deplorable to me that it takes the catastrophe of war to awaken us all to the possibility of a new morality.

Still, if war is the only medicine, let us act like men and welcome it.

HUMANITY is a stuff that does endure. And never before, in the scarlet and gold procession of the history of these islands, has the national character risen to such an emergency nor shown such great endurance.

For what?

Now that the forgotten men and women of Love on the Dole have been remembered; now that, with all the other members of the community, they have magnificently answered all and every call that has been made upon them, what is it that burns in their hearts?

These men and women have stood up to the savagery of the bomber; these men and women have rallied to the ambulances and the fire services: these elderly people forsake their beds to take turns to patrol, steel-hatted, the midnight streets – all these men and women have aroused the sober respect and enthusiasm of the world.

Men and women are resolved that the dead days of yesterday are well and truly dead, that never again are the money-lending financers to rule the roost; but that humanity is to come first and personal greed nowhere at all.

The ten-per-centers, the crooks and the wise guys will not like it. Our New Britain must not take account of them, except to put them where they belong – in the clink.

Britain, with all its unique reservoir of skilled labour and its inventive genius, all encompassed with a tiny green isle intersected with wonderful communications, can and shall take the van and lead the world again as it did in the brave days when British craftsmen and women were supreme (The Sunday Pictorial and the Sunday Mirror, 17 August 1941, p.7 in both cases).

In my book on Greenwood in 2018 I quoted just the paragraph from this Sunday Mirror article opening ‘ I wrote a book, you may remember’ and I realised then it was a very significant paragraph showing the author’s developing view of the relationship between his work, the new film and strongly emerging ideas about the war as ‘a People’s War’ for a ‘New Britain’. However, I now see that actually quoting the whole article greatly expands our understanding of how Greenwood saw the People’s War, and what is more the article has never been referred to at all in any Greenwood scholarship beyond my own too brief citation (1). So, I have put in the whole piece here in order to follow Greenwood’s thoughts in the early forties. I do not think it is one of his best pieces of prose. Indeed, it is unusually clumsy and rhetorical compared to his usual standards, but that may be partly because of the kind of explicit style the Sunday Mirror and Sunday Pictorial preferred for their political articles, and also because it maybe had to be delivered at speed as a journalistic commission (though Greenwood wrote stylistically better pieces under those kinds of conditions). Nevertheless, it is a unique explanation of Greenwood’s People’s War thinking and hence of his sense of the value of Love on the Dole and is well worth a careful commentary given the lack of notice it has received.

First of all the introduction of Greenwood in the central text-box makes a quite grand claim for the new film of Love on the Dole – that it is a ‘picture’ at the centre of public understanding of an emerging new conception of the British State post-war – a ‘New Britain’ in fact. While it has often been agreed that the novel and play of Greenwood (and Gow’s) work tend to avoid blame and partly therefore keep the maximum number of people on side with its distressed but innocent working-people, this is not quite the case with the author’s commentary on the film here. On the contrary, it identifies some specific enemies within who must be fought in conjunction with the external enemy constituted by Nazi Germany.

First the enemies of the ‘New Britain’ are identified in abstract terms as ‘social evils’, and this seems to be a reference to the ongoing work of the Beveridge Commission and its goals. I have not located the source of Greenwood’s quotation. Having searched the full text of the Report posted on the Internet Archive (https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.275849), I can confirm that this exact form of words does not appear in the final Beveridge Report itself, which was not published until November 1942. Beveridge’s goals were (and were usually quoted as) the abolition of the five social evils of ‘Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness’ rather than these three-term goals Greenwood identifies (Beveridge Report, ‘Three Guiding Principles for Recommendations’, paragraph 8). It may be that Greenwood is quoting an early press report on Beveridge’s work. For an account of Greenwood’s responses to Beveridge mainly in his creative work see Walter Greenwood and the Beveridge Report (1941-1945) * .

Then enemies of the New Britain are seen less abstractly as particular social types. These are somewhat variously labelled as those who are not among the ‘honest men [sic], who want to improve civilisation for all’, and those who are ‘counterfeit cheap-jacks, the element which has lived on the success of the most prosperous Victorian generation’. Presumably, these cheap-jacks are not just those who exploit their peers by selling inferior goods at inflated prices in local markets, but also more elite groups who carry out similar business at a national scale, and who fail to distribute the (potential) benefits of the industrial revolution fairly between owners and workers. I note that the very relevant question of empire in the British economy then is not raised, though towards the end of the article Greenwood wants to see British ‘skilled labour’ leading the world as it did in the past, though still without any comment on any imperial or emerging future post-imperial context. Further on, those of ill-will are referred to as ‘the ten-per-centers, the crooks and the wise guys’. Initially, these are seen simply as those who ‘will not like’ the New Britain, but by the end of the sentence they are all three identified as categories of people who should be in jail. The crooks and wise guys are presumably wartime spivs, inheritors at whatever scale of the ‘cheapjack’ tradition which comes down from the [unequally distributed?] successes of Victorian Britain, but who are the ‘ten-per-centers’?

‘Ten-per-centers’ is an uncommon phrase for which OED gives only one really relevant sense: ‘an investor receiving ten per cent interest’. OED also identifies few usages, linking its definition only to a usage from 1902 in the Westminster Gazette (30 July 9/2): ‘Anxious as he is to make every speculative investor in the mines a ten-per-center’. OED gives the phrase a second meaning as referring in the US to a theatrical agent, who will take 10% commission from an author (given the contents of Greenwood’s 1936 novel Standing Room Only, this might seem quite relevant, but I suspect is not!). Searching the British Newspaper Archive suggests to me that ‘ten-per-center’ was not a phrase that was commonly used during the thirties and forties. It is quite surprising to find Greenwood using a phrase in the first half of the twentieth century the meaning of which is now unclear, but such seems to be the case. In the light of his subsequent demand in the article that ‘the money-lending financers shall never again rule the roost’, it seems reasonable to assume that his ‘ten-per-centers’ are in one way or another speculative investors living on unearned income. Greenwood thinks these are comparable to smaller-time crooks and cheap-jacks, just as in the novel of Love on the Dole, he describes the ‘low finance’ operations of Mrs Nattle as ‘conducted on very orthodox lines; to be precise, none other than those of the Bank of England’s or of any other large money-lending concerns’ (p. 103).

Greenwood makes it very clear that he sees total wartime engagement of the kind manifested in ARP work and home defence as needing to remain mobilised into the peace with the related aims of defending and expanding real democracy: ‘Let’s call out a home guard against the social evils which existed’. He even quotes with adaptations of his own the rolling caption by A.V. Alexander at the conclusion of his and Baxter’s film. Here is the original caption:

Our working men and women have responded magnificently to any and every call made upon them. Their reward must be a new Britain. Peace will come. Never again must the unemployed become the forgotten men of the peace.

A.V. Alexander, First Lord of the Admiralty

Here is Greenwood’s adaptation for his manifesto, with a shift in tense:

Now that the forgotten men and women of Love on the Dole have been remembered; now that, with all the other members of the community, they have magnificently answered all and every call that has been made upon them, what is it that burns in their hearts? (2)

Of course, the answer is the hunger for a new and more equal Britain in which unemployment and poverty and inequality are banished into a terrible past. The article is a significant public statement by its author of his perception of the value of the tri-partite text of his Love on the Dole, and it is a value which is primarily social, historical and political with a real world national impact. It is noticeable that this article asserts the unity of all three texts of Love on the Dole, as if there has been no change in its meaning between 1933 and 1941, but it is clear that for Greenwood the meaning of the novel and play has been greatly expanded by the film adaptation and its new wartime context, and perhaps by his work with the director John Baxter in particular. There is thus a retrospective aspect to Greenwood’s assertion here of the unified purpose of Love on the Dole, but it makes a great deal of sense from the perspective of 1941 (given a large addition of optimism about the victorious outcome of the war, and about post-war political developments). Note that this discussion was also published separately as a part of a shorter and differently focused article – see Walter Greenwood’s People’s War Manifesto (Sunday Mirror, 1941).

Quotation 11.

This is a quotation from the Sunday Mirror film review of Love on the Dole by Norah Alexander. She clearly very much admires the film, describing it as ‘flawless’ and rating it ‘ten points out of ten’. Moreover, like Greenwood himself (in, of course, the same newspaper) she sees it as a film of national importance – a film which should ‘shake’ and indeed transform Britain towards a new and different future, so that a repetition of the thirties would be impossible, and so that no future government would tolerate ‘two million men and women to rot in idleness’ (indeed, this became a basic principle of post-war governments of both main parties until at least the nineteen-seventies). These responses are about the political and (widespread) social impact of the film, but Alexander also makes equal claims for the aesthetic and emotional effects of the picture. It is ‘terrific, grim, vital and true to life’, and evokes genuine emotion rather than the sentimental responses of a ‘weepie’. Nevertheless, overall, its effects are forward-looking and optimistic, as well as being widely accessible, so that everyone should go to see it. This review sees the film as valuable as a work of art and as an influential social and political work with long-lasting impacts.

A FILM TO SHAKE BRITAIN

WHAT a difference a war makes! Time after time our censors have waxed apoplectic at the suggestion that Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole was fit subject for a film. A novel about unemployment was one thing, but a picture for the world to see was obviously another. Various changes, they insisted, would be necessary before any script would pass.

Now, with unemployment a minor headache, the moralists have relaxed. And the film has been made at last without any major changes. The result is terrific, grim, vital and completely true to life. You know how I feel about ‘weepies’, how one joke sends the score soaring and one sniff makes it sink. This film made me cry myself bleary-eyed. But it is not depressing. On the contrary, it holds enormous promise for the future. If every man and woman in Britain could see this film. I don’t think we would ever go back to those dreadful pre-war years when two million men and women were allowed to rot in idleness. I don’t think the censors meant us to feel that way about it, but Walter Greenwood did. He succeeds magnificently. So, I beg you, please, please go. It is flawless. and it will win world fame. I rate it ten points out of ten (Norah Alexander, Sunday Mirror, 1 June 1941, p.12).

Quotation 12.

The reception of the Granada production was mainly positive, with considerable commentary on relationships between the thirties and the sixties. The Crewe Chronicle was unusual in arguing that the adaptation by Granada and all it brought to mind was mainly irrelevant in a time of full employment. The review asserts that people no longer want to identify as being working class in the allegedly ‘affluent’ and allegedly ‘post-class’ society of the nineteen-sixties. Love on the Dole therefore has no life left in it for contemporary audiences – it is ‘outdated’ and speaks to no-one about suffering with which they do not identify nor feel they are likely to experience. Indeed, the review is (surely over-optimistically) sure that unemployment and poverty are gone for ever in an ‘age of wealthy, all-pervading . . . well-organised trade unionism’. Even if such conditions of poverty were historical facts, the reviewer feels we would rather close out eyes to that history and to potential cross-class unity of that experience through the ‘commonplace unity of families’.

No one readily admits to being working-class these days – all part of the snobbery of belonging to a so-called affluent society, I suppose – and consequently much of the emotional torment poured Into Walter Greenwood’s novel, Love on the Dole . . . seemed outdated and quite incapable of triggering off any warnings about the misery and indignity of being out of work.

Frankly, I doubt if people want to know about or be reminded of the bad old days . . . in an age of wealthy, all-pervading, complex, but well-organised trade unionism, the raw melodrama of Love on the Dole and the commonplace uniting of families in eternal penury is something we’d rather not know about.

It may be, of course, that Granada, in commissioning this play, thought it would serve as a salutary reminder that the riches so glibly enjoyed in The Forsyte Saga (running along so splendidly on BBC 2) were far from being freely available (Laurence Shelley, Television column, 26/1/1967, p.2)

Quotation 13.

This is one of a number of articles and interviews sparked off by the premier of the stage adaptation of Greenwood’s memoir There was a Time at the Mermaid Theatre in London in 1971. Keith Dewhurst (born 1931) is a well-known playwright and scriptwriter, and, among many other works, author of the superb stage versions of Flora Thompson’s Larkrise and Candleford (1978 – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lark_Rise_to_Candleford). His very thoughtful review looked back over Greenwood’s reputation and impact on British writing in the twentieth century. He approaches Greenwood’s writing both as a widely and immediately accessible medium, but also as one which has been so influential precisely because it distances itself from the fierce indignation which Greenwood felt about the conditions of life for his peers in the thirties: he works through the aesthetics of his fiction rather than through the originating anger which motivated it. Indeed, the whole of Dewhurst’s substantial article articulates Greenwood’s unique achievement as stemming from balance – between anger and objectivity, between documentary and the personal, between popularity and seriousness, between the use of traditional forms and new purposes and new ‘mass’ tastes, between realist detail and mythical resonances. Dewhurst values Love on the Dole for its witness to a major aspect of the twentieth century but also notably for its aesthetic and formal decisions, made by a conscientious artist, and which he clearly sees as forming a permanent part of both British history and the literary canon.

With Love on the Dole [Greenwood] . . . is part of English literature and of the history of English society and taste . . . Walter Greenwood is not a great highbrow master like D.H. Lawrence but he is and always has been a truly popular writer – a man of the people who entertains all sorts and conditions and appeals instantly and directly to their hearts. He is the only English novelist since Dickens who has combined true mass appeal, passionate radicalism. and bitterly honest documentation with writing of high artistic quality . . . the paradox and fascination of [Love on the Dole] is that although the situation gave Walter Greenwood a pen of fire it is his approach to fiction that makes his work a classic. It is the only book of its kind in which modern documentation and personal outrage are combined with the sort of storylines and situations that belonged to the plays and novels of the romantic epoch.

Greenwood makes us identify with characters who are ugly, dirty and louse-ridden and the reason is that Love on the Dole has a touch of genuine myth. Its characters, like Sam Grundy, Sal Hardcastle and Larry Meath are described in everyday convincing detail: they are also human types who depict simple but fundamental attitudes and choices.

The artistic forms [Greenwood] saw in the many Manchester theatres, heard in concerts, and followed in his own reading were not those of contemporary highbrow art: of Joyce or Schoenberg or Shaw of Strindberg or Picasso. They were the solid storylines, the high passions and the vivid human incidents of popular melodrama and romantic classics . . . [but Love on the Dole] is also a landmark of the mass age and of a new kind of taste.

In [it] Greenwood maintained for many furious pages what so many films and especially television people have striven for as an ideal: a balance between popularity and serious integrity.

. . .

The old fox knows what he’s writing and no mistake (Keith Dewhurst, ‘Greenwood’s Grass Roots’, the Guardian, 2 April, 1971, p.10).

Quotation 14.

This observation by Irving Wardle sees a few elements, principally the idealistic Larry and his story, as unlikely to work still for the contemporary audiences of 1980, but mainly sees the play as surviving strongly in its own right as a piece of drama with an inherent logic and therefore vitality which is as accessible to audiences as it was in 1934. Wardle acutely brings out the way in which the Hardcastle family are bit by bit pushed over the cliff between barely managing and not managing, how their absolutely minimal hopes (for some new clothes, some free diversion, for love and a future) are also part of what ensures their destruction, – unaffordable luxuries, as much as a car or champagne.

Still holding its Unique Place

Ronald Gow’s adaptation [sic] of Walter Greenwood’s novel [Love on the Dole] enjoys a unique place in the British repertory as an expression of the working-class social conscience which has enjoyed lasting favour with the bourgeois public. There are passages in it that have gone soft in the 46 years since its first performance such the as the idealised figure of Larry, the golden-hearted agitator, and the pathetic circumstances of his death. But if I had to pick between the dehumanised products of the modern political stage and Greenwood and Gow’s preference for people before ideology, I know which I would choose.

Aside from Larry’s martyrdom, nothing in the play is contrived. It simply shows a Salford family hit by the slump and steadily disintegrating as the slump gets worse. To start with the Hardcastles are a self-respecting family under a father who is still master in his own house. By the end, his manhood has been crushed, his children driven out and their love relationships in ruins, all because of money. The message is that love and family life are as far beyond their means as cars and champagne.

Considering how powerless they are to resist what is happening to them the play marks an extraordinary triumph of manner over matter. Without blurring the picture, it evokes a world of social distress through gritty detail and phlegmatic northern gags. It leaves pity up to the spectator, and shows the effects of poverty with an almost clinical irony. These blinkered people are always looking forward to tiny treats: getting a suit from the clothing club, a spiritual séances, and walking straight into the biological trap which will keep them forever imprisoned in Hanky Park (a review of a production at the Royal Exchange, Manchester, The Times, 23 April 1980, p. 3).

Some Conclusions

While the absolute distinction between valuing Love on the Dole in the short-term and the long-term perhaps overstates a binary opposition, since nearly all the long-term estimations also judged the work as having an immediate impact, it does bring out a marked variation between those who saw Greenwood (and Gow’s) work as being tied to a time-limited context and those who saw it as having a longer life as a self-contained literary, dramatic or cinematic work beyond that original context, or who saw that context as itself never fully fading from British history, literature and cultural memory.

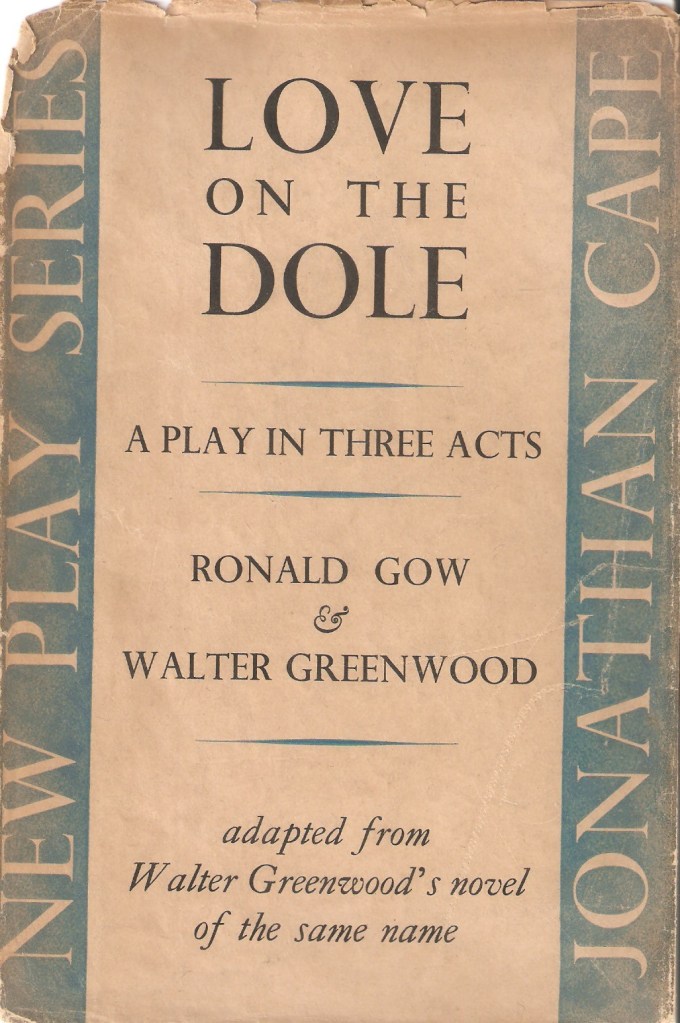

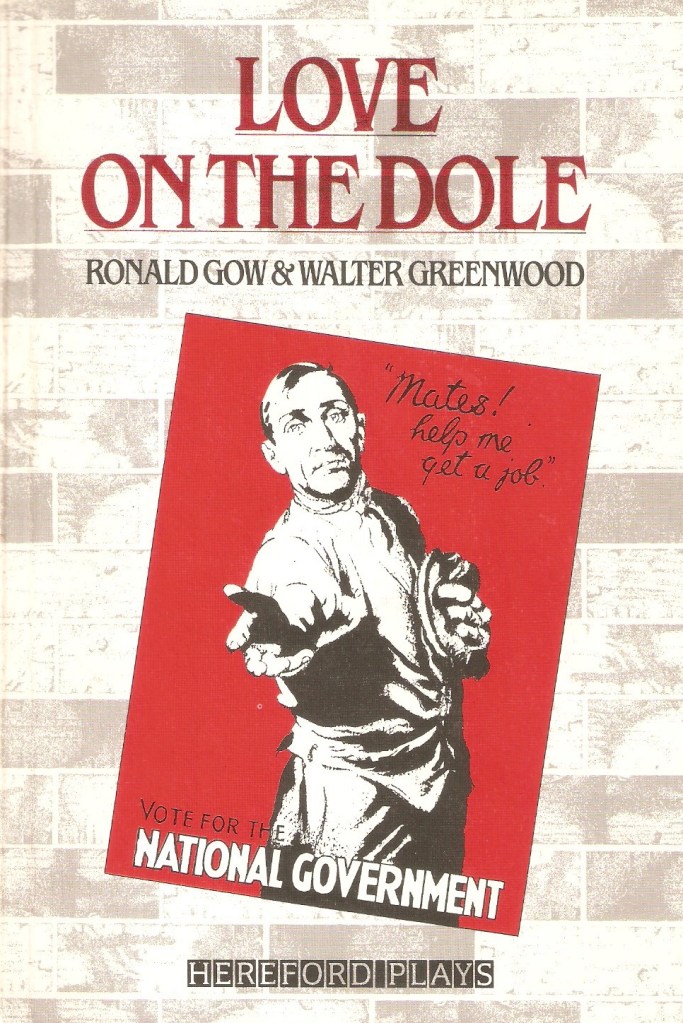

No one has ever quite asserted, as the Athenian historian Thucydides did of his own work in his Preface to the History of the Peloponnesian Wars (5th century BC), that Love on the Dole is a ‘Ktema eis Aei’ [Κτημα εισ άεí], ‘a possession for ever’, but the TLS view that it would remain in print for at least a century so far looks likely to be an accurate prediction. Jonathan Cape kept the novel in print from 1933 until 1968, after which they agreed to let Penguin to bring out their paperback edition in 1969 (they also agreed to a Four Square Books paperback edition in 1958, and a Consul Books paperback in 1965). The Penguin edition, which surely sold hundreds of thousands of copies, stayed in print until 1993 when it was transferred to a new Vintage edition which is still in print in 2024 (though it has had three different cover designs in that period). By 1993 Random House owned Penguin and had established the new Vintage imprint, so in fact there was a considerable continuity in the publishing history of Greenwood’s novel, which so far has been in continuous print for ninety-one years. Greenwood and Gow’s play version was also published by Jonathan Cape in 1935, and in an acting edition by Samuel French in the same year. I am not certain how long Cape kept their play edition in print, but the Samuel French edition has never been out of print and is still the readiest text for both professionals and amateurs contemplating a production (of course the more such contemplations the better, in my view). There was also a very useful new educational edition published by Heinemann Books in 1986 in their Hereford Plays series, with an informative introduction by Ray Speakman, and with considerable input from Ronald Gow.

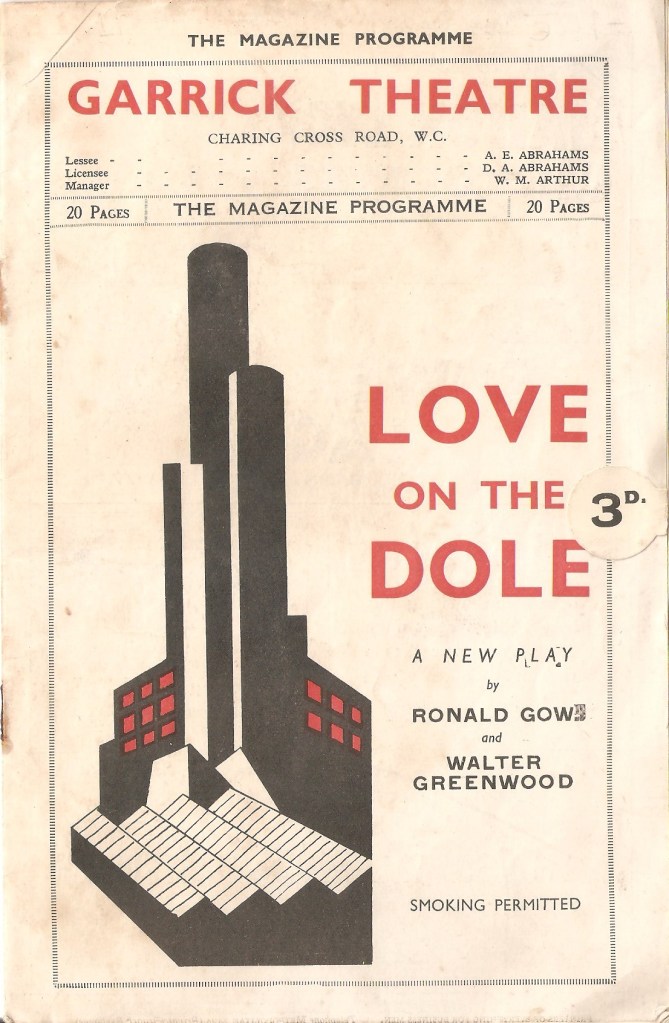

The three editions of the play of Love on the Dole (1935, 1934 and 1986). Images scanned from copies in the Author’s Greenwood collection.

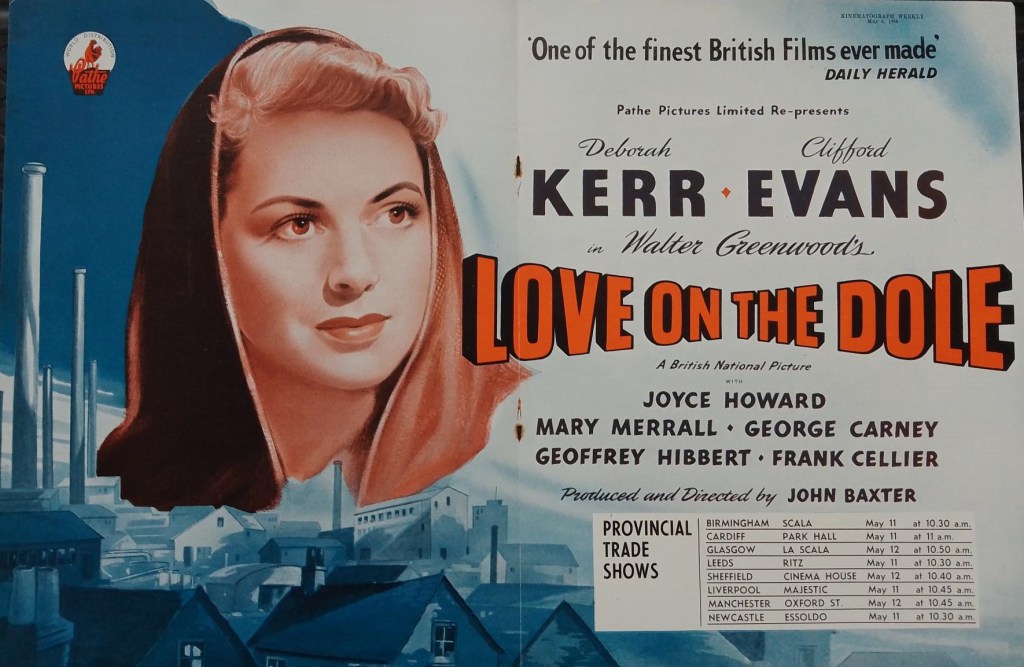

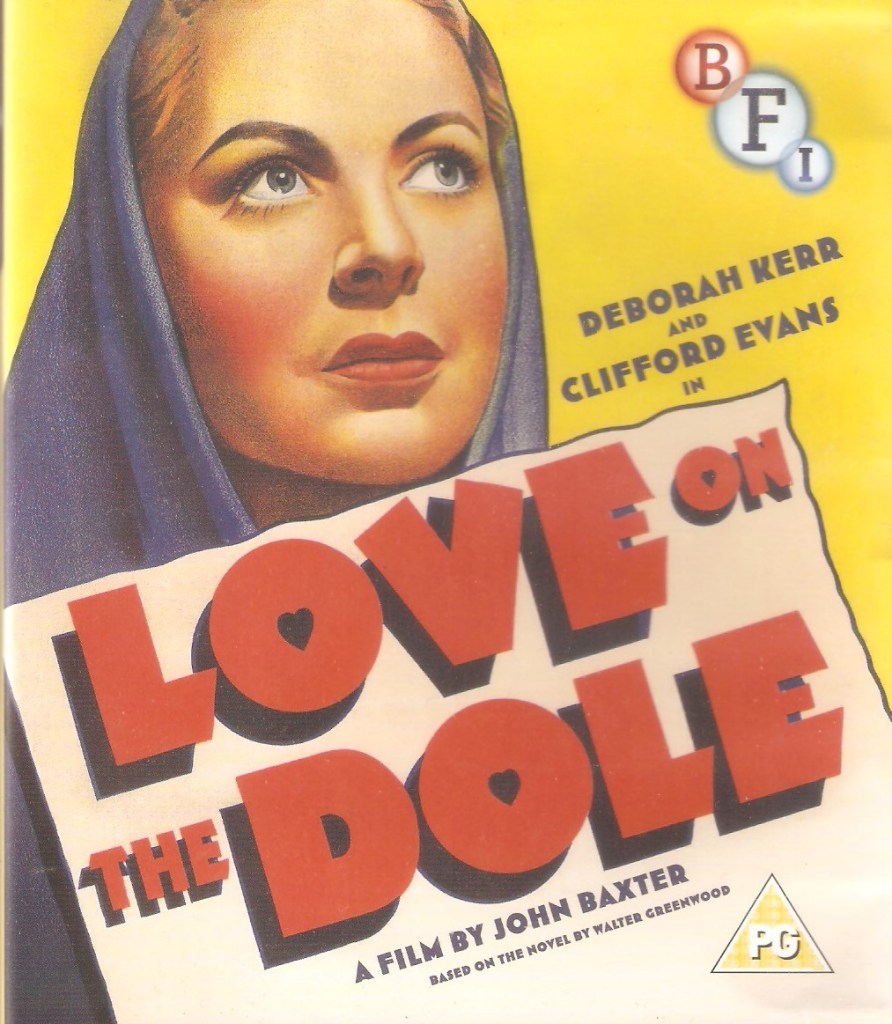

The film of Love on the Dole was shown in British (as well as Australian and New Zealand) cinemas pretty much continuously from its release in 1941 until 1947, and then there was a re-release in 1948 by a different distributor, Pathé Pictures Ltd (in place of Anglo-American Films), which must have been intended to stimulate fresh interest in a film whose war-time judgements on the thirties and prophecies could now be contemplated from a post-war perspective. Indeed, frequent cinema screenings of Love on the Dole in Britain continued until at least 1953, when cinemas in Skegness, Leicester and Roscommon screened the film between March and September of that year, as is shown by cinema adverts in the regional newspapers. Once television became established as a new mass-viewing medium at about the same time, the film of Love on the Dole was also frequently aired, with dozens of broadcasts of Greenwood and Baxter’s film between 1950 and the present. The film was available from 1998 in a VHS recording (Fabulous Films) and then in a DVD edition from 2004 (also by Fabulous Films), and is currently available in a BFI DVD / Bluray high definition transfer, released in 2016, with a booklet giving contextual introductions. Copies of the full-length movie appear (though not always for long, and with perhaps rather unclear copyright status) on Youtube. At present there is a ‘colourized’ version of Love on the Dole (Cult Cinema Classics) of which I should disapprove given the careful and appropriate choice of sepia over black and white by John Baxter, but which actually I think is nicely done (if you like that kind of revision towards contemporary taste) – see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjurc5Mku8s .

Six images representing some of the various editions of Love on the Dole in its various genres and media: the first edition dust-wrapper (1933), the programme for the Garrick production of the play (1935), the Kinematograph Weekly trade advert from 1941, the Kinematograph Weekly trade advert for the 1948 re-release, the 1998 Fabulous Films DVD case, and finally the BFI DVD/Bluray case from 2016. I should point out that at no point in the film does Sally Hardcastle (Deborah Kerr) appear in the nun-like shawl which three of these images feature. Other mill-girl workers appear clad in the traditional shawl, but Sally never does. Images scanned or photographed from copies of theses editions in the Author’s Greenwood collection.

There are clearly many ways of valuing and remembering the triple texts of Love on the Dole. One of the things I have been impressed by in writing this article is the generally high standards of writing and thinking in the novel, play and film reviews written by both regional and national journalists for the usual demanding deadlines and word-limits. I am hoping that at the very least all three versions of Love on the Dole are still accessible to as wide an evaluating and critical audience as possible in 2033, a century after their origin in Walter Greenwood’s manuscript, which was published by Cape perhaps rather against the odds. At the present time, there still seems to be plenty of life in Love on the Dole.

NOTES

Note 1. Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole: Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, 2018, p. 184.

Note 2. As discussed in my book, Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole: Novel, Play, Film, pp. 173-4, there has been a view that A. V. Alexander’s caption was only added to the 1948 re-release of the film of Love on the Dole, but Greenwood’s own close reference to the caption here reinforces my evidence that the caption was already present in the 1941 release, since a number of reviews make clear verbatim reference to it.