1. Rejections and Acceptances – Putnam and Cape

In his memoir, There Was a Time – Walter Greenwood Remembers (Jonathan Cape, 1967), Greenwood wrote of the period between 1929 to 1932 when while unemployed he wrote and sent off his first novel typescripts to publishers – and of their frequent return without acceptance:

A brisk knock on our door. My hopeful expectation was dispelled the instant the postman handed me a bulky foolscap envelope. The publisher’s letter clipped to the novel’s cover was terse. It regretted that my offering was not suitable for inclusion in his list and it also served as a reminder that the way ahead was to be long, hard and discouraging with no guarantee of ultimate success (p. 205).

This is not completely certain, but Greenwood was probably sending out two different long works in typescripts in this period: part (volume one?) of his three-volume historical novel about the industrial revolution in Lancashire, The Prosperous Years, and towards the end of the period his typescript of Love on the Dole (though it had not yet acquired that title). (1) He may also have been sending out a short-story collection, later expanded into his 1937 collection The Cleft Stick (see: https://waltergreenwoodnotjustloveonthedole.com/walter-greenwood-and-arthur-wraggs-the-cleft-stick-1937/). A little later in the memoir, with the Depression at its height (or rather depth), Greenwood recalls just before Christmas (1931, I think) another rejection, this time clearly of the novel which was to become Love on the Dole:

A few days before Christmas the postman handed me, together with some Christmas cards, a package with one of the publisher’s labels prominently displayed. Deflated, confounded, I opened the package.

‘Dear Sir,

We have read your novel with great interest. Unfortunately our Spring List is to include a book on a similar theme translated from the German, Mr Hans Fallada’s Little Man, What Now? . . .‘

Oh, well. Never say die. There was the other publisher who, doubt whispered spitefully, might also at this moment be sending the book back (p.249).

In fact the sequel, further down the same page, turns Greenwood’s run of rejections, and indeed transforms his life. On a ‘bitter January morning’, his sister, getting ready for work, brings him a cup of tea and a letter in bed:

The letter began:

‘Dear Sir,

We will publish your novel . . . I was on the threshold of a wonderful year, though this I did not know’ (p.249).

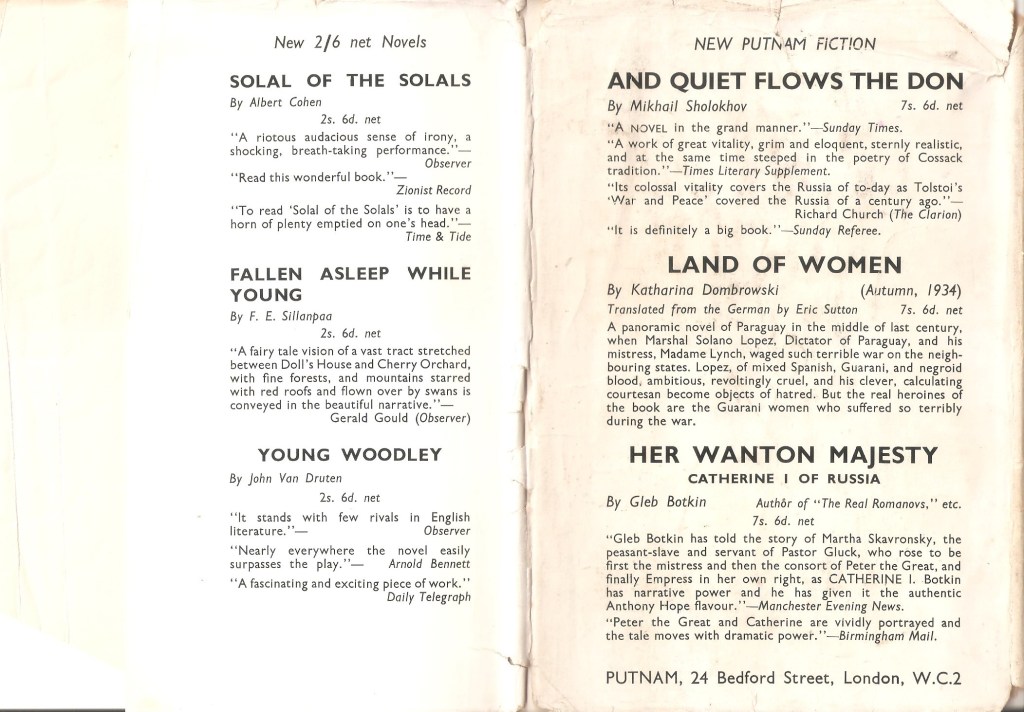

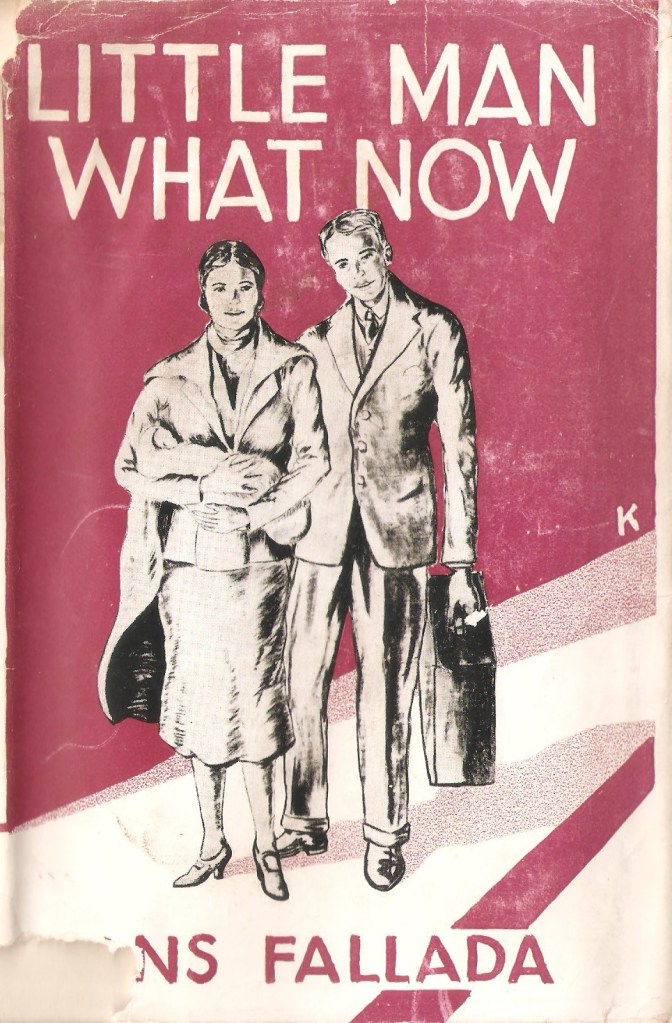

In the end then Jonathan Cape made up for Putnam’s rejection, and strictly speaking my use of the word ‘instead’ in the title of this article is not quite right – for Putnam did not choose Fallada (1883-1947) over Greenwood, but had already accepted his novel, Kleiner Mann – Was Nun?, before they saw Love on the Dole. They thus published a work which was anyway in line with their interest at this period in publishing international narratives, some historical and others describing the contemporary global economic crisis, as the dust-wrapper advertising of Little Man What Now shows (rear of dust-wrapper plus the rear inner flap, scanned from copy of the Putnam second edition from May 1934, translated by Eric Sutton, in the author’s collection).

Still, Putnam’s professional readers saw the two novels as having close similarities, so it seems worth comparing the two, which both gained considerable fame and a critical reputation in the thirties, as well as being filmed (both met censorship issues of very different kinds though while Greenwood had to wait till 1940 for his film, Fallada’s novel was filmed in Germany in 1933 and in the USA in 1934). (2) This article will compare the two novels as narratives of the depression, unemployment and poverty.

2. Dust-wrapper Signals – Similarities and Differences

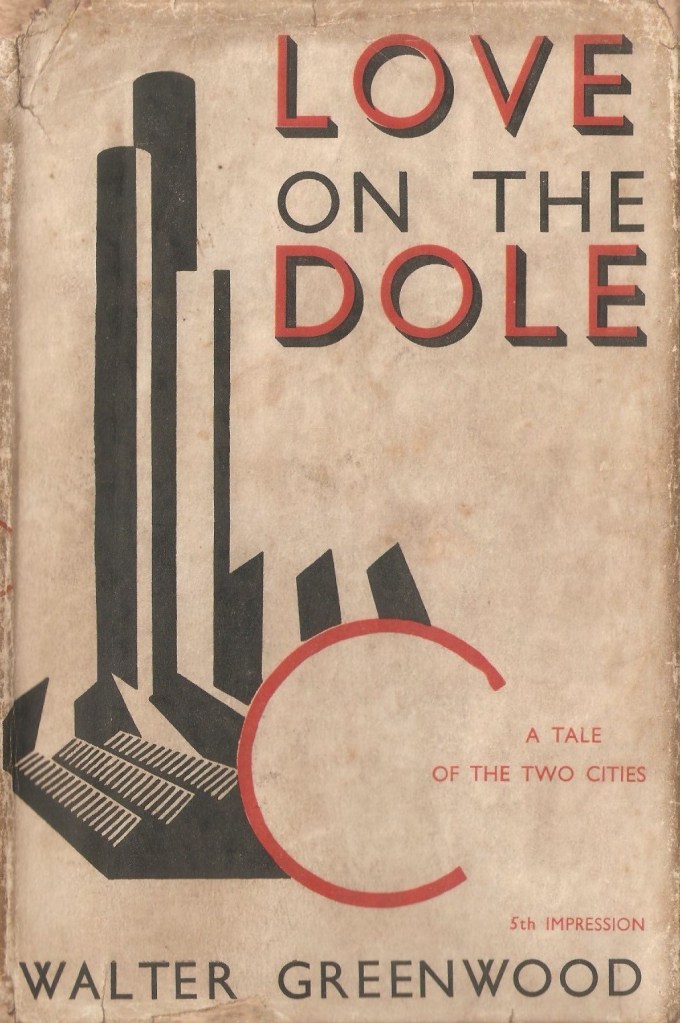

Let us begin by looking at the dust-wrappers in which the two were published in Britain:

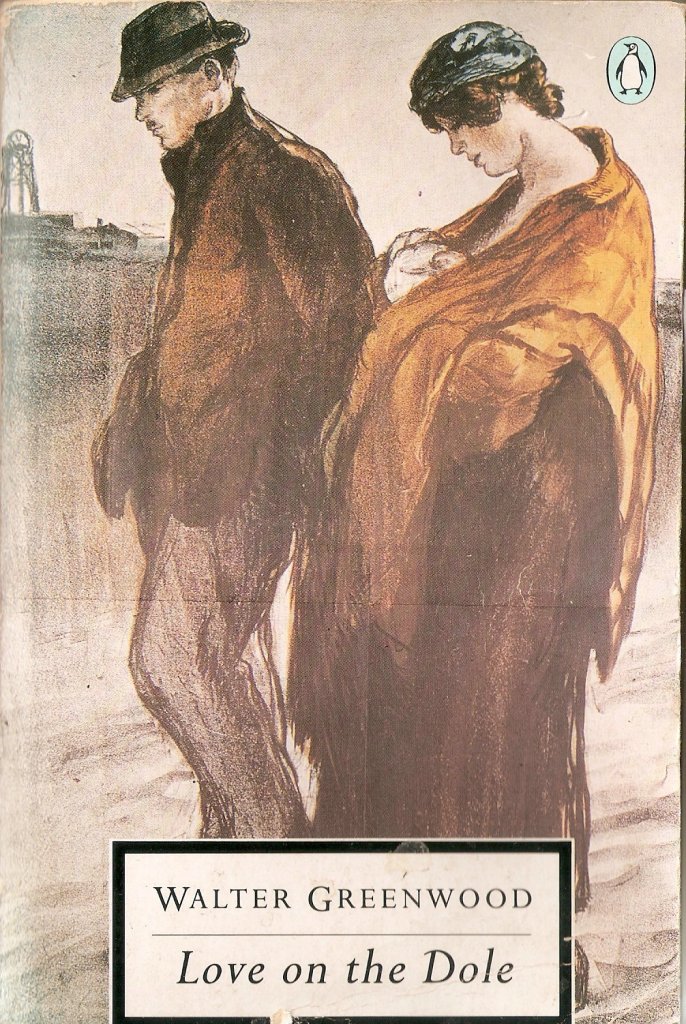

Both first-edition dust-wrappers are printed with two colour designs (black/red and black/purple respectively) which also make substantial use of the base tone of their cream or white paper background. The Greenwood design focuses on an industrial building (Marlowe’s engineering works), perhaps suggesting insight into what happens within through the slightly mystifying C which may be a kind of section into the inner workings of the factory. The Fallada cover (signed simply ‘K’) differs markedly in focussing on the people at the centre of unemployment, showing the couple tramping the pavements with their baby and a suitcase, presumably because they have nowhere else to go. However, the Fallada cover is much more like the cover with which the Penguin edition of Love on the Dole was marketed over a period of some three decades, from the nineteen-sixties till the nineteen-nineties.

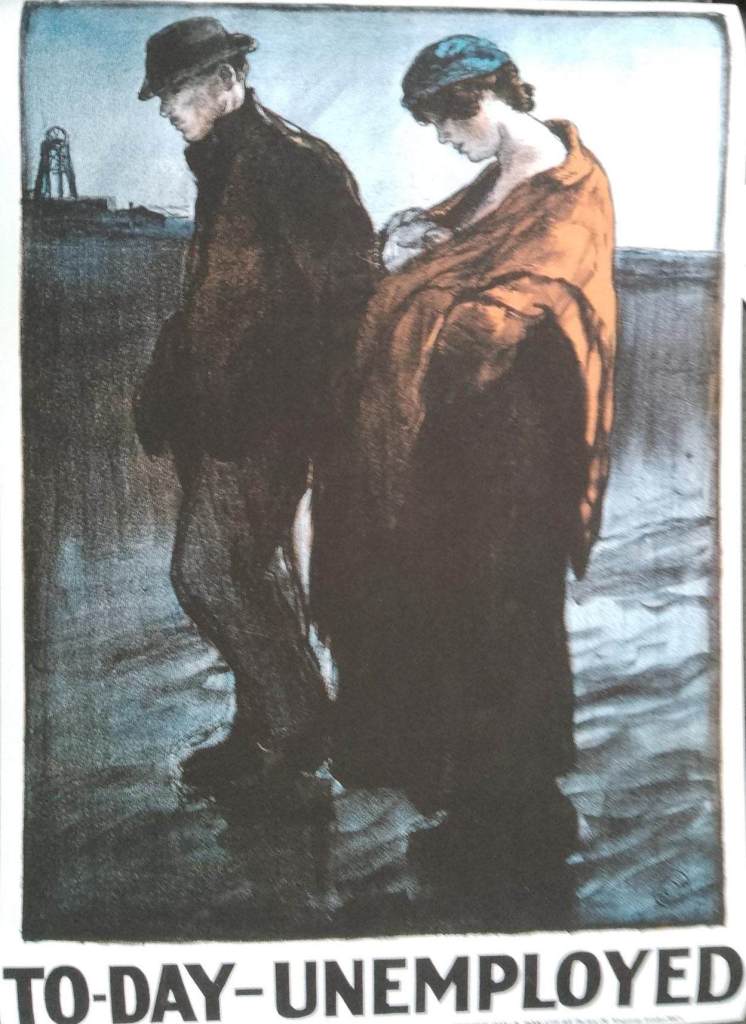

This image again represents unemployment through the family unit of mother, father and baby seen out on the street. There are though some differences: the Fallada cover implies through the suitcase that the family are homeless, which the Greenwood image does not necessarily do. The Fallada family are relatively smartly dressed in that the father wears a suit, shirt and tie, while the mother also wears a relatively fashionable costume and high-heeled shoes. The Greenwood father wears a jacket and a trilby, but both are clearly battered, and his collar is turned up against the cold. The mother does have what looks like a reasonably fashionable hat, but also wears the traditional Lancashire shawl, which was flexible and practical, but also a sign of working-class status, and, as references in the novel suggest, becoming seen as an old-fashioned garment by the early nineteen-thirties (we cannot see the couple’s shoes because of the placing of the novel title in the Penguin cover design, but in the original poster they do not look fashionable, though they are obscurely depicted). While Fallada’s couple are imagined as bourgeois, Greenwood’s are clearly working-class. As important as these class signifiers in the Greenwood cover is the use of colour: clothes and (disused?) pithead are both drab, with the narrow range of greys and browns making the human figures very much part of a colourless and empty industrial landscape, with even their facial tones almost matching the unhealthy looking pinkish sky, perhaps from the white swirls within it, a representation of industrial smog. Nevertheless, each figure retains their dignity. Both these covers though focus on two individuals damaged by the depression, while the original Love on the Dole cover focused more on the industrial system of production which had failed.

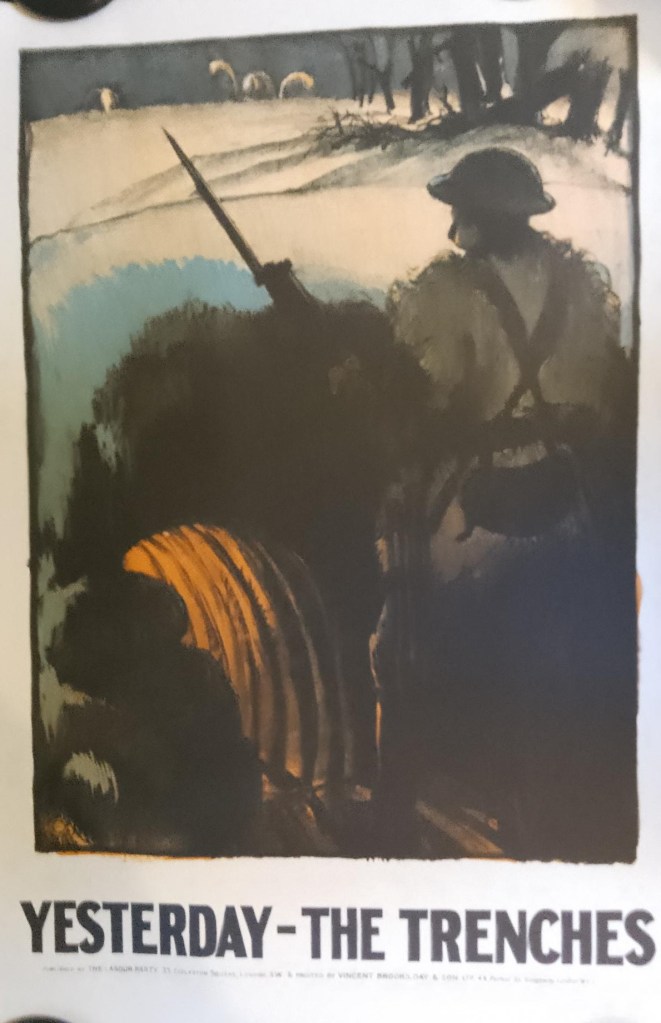

The Penguin cover is taken from one of two posters which in effect formed a diptych and were originally designed as a Labour Party posters in 1923 by Gerald Spencer Pryse (1882-1956). The other poster showed two British soldiers in a trench and had the caption: ‘Yesterday – the Trenches’, while this image was captioned ‘Today – Unemployed’. Here are photographs of the two posters in my collection (or in fact what I think are reproductions from the nineteen-seventies). Both, in a small font at the bottom which I have not been able to capture in these photographs, have a credit: ‘Published by the Labour Party 33 Eccleston Square, London, S.W. & Printed by Vincent Brooks Day & Son Ltd. 48 Parker St. Kingsway London W.C.2’. The First World War image, including the figure, is more impressionistic in style, with the appropriate exception of the sharply delineated bayonet. The unemployed image has more clearly delineated figures against an impressionistic background. The colour values in the unemployed poster are clearly much darker / bluer than in the printing of the image on the Penguin cover-design, giving a perhaps more conventional sense of a polluted industrial landscape into which the pale-faced / sun-deprived human figures with their dark clothing blend.

Oddly, Penguin, despite using the image for some three decades, did not acknowledge Pryse’s work nor give any source for the image, which surely was an excellent choice for Greenwood’s novel. (3)

Oddly in Germany, Fallada’s novel was first published with a monochrome line-drawing of an entirely happy domestic scene of a mother with her baby in a crib. It gave no hint of unemployment, homelessness and poverty. The first German edition is not that easily obtainable, the German post-war edition of 1958 had a drawing in a very similar style again suggesting a novel about a wholly happy family. The first British edition dust-wrapper design seems better suited to the actual narrative and concerns of Fallada’s work.

3. Couples, Families, Places and Communities

In fact, while a couple (Sally Hardcastle and Larry Meath) are important in the novel of Love on the Dole, it really focuses on the experience of a family, the Hardcastles, as well as some of their neighbours and so gives a picture of the whole community of Hanky Park, while a couple are more truly at the centre of Little Man, What Now? Fallada’s novel opens directly with that couple, Herr Pinneberg (referred to by his surname throughout) and his intended, Bunny (called by that nickname throughout, though more formally she is a few times referred to as Emma Mörschel). The novel opens directly in another way too: the couple are visiting a Doctor, and have even paid from their very meagre savings to be seen as private rather than as ‘panel patients’. Pinneberg has chosen this doctor, Dr Sesam, because he has a reputation as a good and generous man, and because Pinneberg knows he has ‘written a popular pamphlet on sexual problems’ (p.6). The problem they want to know the answer to is how to avoid having children until they can afford it (they present themselves as married, which they are not as yet). Dr Sesam is sympathetic to this request, but, as he soon discovers, they have asked the question too late – Bunny is in fact already pregnant (‘a little too late for precautions, Herr Pinneberg’, p.9). They ask if anything can be done but of course he says it cannot, tells them they will manage, and says they should come back in due course so he can advise on birth control for the future. The two decide they should get married – but their material circumstances will make life very difficult, since they live and work in different towns and have very little income.

Their situation is of course very similar in many ways to that of Harry Hardcastle and Helen Hawkins, who also have to marry for the same reasons, but have nowhere near enough income to live on, or indeed to pay for anywhere to live. However, the explicitness of Fallada’s opening, including some of the conversations with Dr Sesam, would have been very surprising in a British novel, and I think would have prevented Love on the Dole from easily being published. Greenwood clearly was interested in birth control and in the role its lack of availability played in the constant reproduction of poverty, as a number of pretty discreet comments in his novel suggest, but he does not seem to have thought he could be any more open about the topic. Fallada felt able to write more openly about the subject – though one should note that the complete ignorance of the Pinnebergs about sex and pregnancy are at almost exactly the same level as that of Harry and Helen up to this point.

Neither do Pinneberg and Bunny reflect any more widely about the situation of the poorly paid in a society in which it is considered more ‘respectable’ to know nothing until it is too late – though even in this opening scene Bunny shows some of her socialist convictions. Since they are paying for their appointment, the two are taken into see the doctor ahead of thirty queuing ‘panel patients’. While Pinneberg is pleased to get in first, Bunny is furious about the discrimination made against ordinary health insurance patients: ‘ “How disgusting!”, said Bunny. “We’re usually panel patients. Now we know what doctors think of us” ‘ (p.5). This is the first indication of a distinction between Bunny and Pinneberg: while she comes from a Socialist background and has some sense of political issues and principles, Pinneberg almost never shows any explicit political consciousness (and avoids both the Nazi and Communist party members who are there in the background throughout the novel). Of course characters in Love on the Dole also show a wide range of political awareness from practically none (Harry Hardcastle) to a deep engagement (Larry Meath, but also in her own way Mrs Bull, who does hint to Helen Hawkins the desirability of contraception once she has had her first unplanned baby).

After this news, Bunny and Pinneberg have to make some plans about what to do next. Once they have told Bunny’s parents that they intend to marry (the parents have no doubts about why there is an urgency), the two have detailed discussions about incomes and outgoings and are certain that life is going to be very difficult. Nevertheless, they very quickly do marry. However, there are a some things which Pinneberg does not reveal to Bunny which will intensify the degree of their difficulties: he works at a very low-wage for a corn-merchant who expects him to marry his daughter, whom Pinneberg finds not at all attractive. He knows very well that he will be sacked if he does not marry her, and of course now he is already married that he cannot do. He therefore plans to continue as if unmarried and must keep Bunny a secret – though he does not tell her that. They go to live in a single room in a widow’s small house, it being of course all they can afford. Not only is the room also very small but it is already full of the widow’s spare furniture:

Well: the room was a sort of cleft or passage, not particularly narrow, but very very long. Four fifths of it were stacked with upholstered furniture, walnut tables, overmantels, consoles, flower-stands, whatnots, and a large parrot-cage (without parrot); in the last fifth there were two beds and a wash-hand stand.

. . . ‘Oh, Lord!’ said Bunny, and sat down. (p.47)

Presumably the old-fashioned and heavy furniture is left over from better days, and though it positively gets in the way of living is clung on to as a kind of material memory of that past. That may be quite reasonable from the widow’s point of view, but of course it is not Bunny and Pinneberg’s life it attests to: instead they have practical needs for the present to which it is merely one of many obstacles.

Needless to say, their obstacles soon increase rather than diminish. Pinneberg finds that his alcoholic boss is determined to sack one of his three employees because trade is bad and he is himself increasingly incapable of running his business – and puts it to Pinneberg that if he does not marry his daughter it will be him who has to go. Meanwhile, Pinneberg spends much nervous energy trying to make sure that he is not seen with his new wife, because he knows the news will quickly spread. In fact, he cannot bear to keep his secret and tells Bunny about his situation. Inevitably, the married couple are seen by the boss out walking one Saturday when Pinneberg has said he cannot work overtime because of another commitment, and he is immediately dismissed. He is now in the situation of Mr Hardcastle and Harry Hardcastle – looking for work and knowing there is none.

There are differences too though between the situations in Fallada’s and Greenwood’s novels. While Love on the Dole is about a family and a community who are deeply rooted in a place, Hanky Park, and its industries, despite their utter lack of economic security, Pinneberg and Bunny are located in a place, the fictional town of Ducherow, where they are both strangers. Where the Hardcastles and all their neighbours are firmly working-class, Pinneberg works as a clerk or shop-worker, though he observes that he is really financially no better off than a working-man. Pinneberg has already lost one job and had to move to Ducherow to take the not very desirable job of assistant to a corn and seed merchant, and knows no-one apart from his two fellow juniors. Neither is very comradely: Lauterbach is a keen Nazi, whose conversation has the repetitive themes one would expect, and who most enjoys assaulting the opponents and victims of the Party in the street, while Schulz is interested only in pursuing a string of simultaneous girl-friends and is always in one fix or another as a result. While the Hardcastles and their neighbours have no means to be anywhere except Hanky Park – except for the rambles on the moors which Larry Meath introduces Sally Hardcastle to, and which are a real novelty to her, the Pinnebergs do not remain in Ducherow for long, and in fact spend much of the novel moving from place to place. Against the imprisoning rootedness of Hanky Park, they experience instead a rootless lack of belonging or community.

Love on the Dole is full of its characters’ thoughts of how near impossible it is to move on from or escape from Hanky Park, with frequent use of words and phrases such as ‘escape’, ‘prisoners’ and ‘getting out’:

[Helen thinking about her home life] ‘Dully, insistently, crushing came the realization that there was no escape, save in dreams. All was a tangle; reality was too hideous to look upon: it could not be shrouded or titivated for long by the reading of cheap novelettes or the spectacle of films of spacious lives. They were only opiates and left a keener edge on hunger, made more loathsome reality’s sores’ (p.65).

[Harry on his once in a life-time holiday in Blackpool with Helen] ‘They were Hanky Park’s prisoners on ticket of leave.’ (p.122)

[Larry thinking about Sally] ‘‘Oh, if only there were a loophole, just a frail, unlikely, possibility of getting out of Hanky Park … God, if only there was.… I wouldn’t hesitate.… I’d marry her tomorrow’ (p.146).

[Harry once unemployed] ‘He suddenly wakened to the fact that he was a prisoner’ (p.171).

In contrast, the Pinnebergs spend much of their time moving on – not of course because of their successes but because of repeated failures, because Pinneberg gets into one trouble after another in the jobs he briefly secures, because jobs are so scarce that it is easy for any employer to sack someone and replace them at lower wages. From Ducherow, they go to Berlin, where they stay first with Pinneberg’s mother, who writes to tell him she can get him a job, and then denies all knowledge of her offer, before marginally involving the couple in what is clearly a criminal enterprise involving cheating at cards and possibly some kind of sex work. The young couple cannot live in this environment (and indeed are not financially provided for in it) and soon move to an illegally rented room over a cinema (entered via a long ladder) and finally then to a damp wooden hut in the woods, surviving on what domestic work Bunny can get. Many subsisting in the hut village have chosen either Communism or Nazism as their hoped for salvation, but still Pinneberg keeps away from both groups as much as possible, saying he cannot make up his mind, and very aware of potential violence. In a society increasingly made up of mass movements, he tries to be a lone individual.

Though this might not sound like a very extravagant amount of travel, I think Fallada’s novel does have something of the feel of an eighteenth-century picaresque novel – that is a novel full of unplanned journeys, of random meetings, and unexpected incidents. However, in that genre things normally work out in the end, often providentially, whereas in this nineteen-thirties version there is no providential ending, and indeed no substantial conclusion at all: in the ‘Epilogue: Life Goes on’, the Pinnebergs are left in a kind of limbo, with no proper housing, and no obvious future or remedy. Bunny brings in some money from sewing and cleaning, and Pinneberg is well aware that there has been a reversal of the usual gender roles of the time, since he does the housework in the hut, and looks after the baby. Indeed, the second section of the Epilogue is partly titled ‘Man as Woman’ (p.402). This role reversal is not something which happens in Love on the Dole, but is a major theme in Means Test Man (1935) by Greenwood’s Derbyshire contemporary, Walter Brierley (1900-1972). Fallada’s novel ends on a relatively optimistic (if unjustified?) note, which suggests not quite that love conquers all, but that it can mitigate material circumstances:

[Pinneberg] sobbed, and stammered out : ‘Oh, Bunny, do you know what they’ve done to me . . . the police . . . they shoved me off the pavement . . . they chased me away . . . How can I look anyone in the face again —?

And suddenly the cold had gone, an infinite soft green wave raised her up, and him with her. They slid onwards, and the twinkling stars came very near. She whispered: ‘But you can always look at me, and we are together —‘. (p.441). [Ellipses as in original].

This is the opposite of what Love on the Dole concludes about the power of love or any other inward experience when faced with material deprivation and the absence of any alternatives. Once Larry is dead, and she has made the choice which is no choice to become Sam Grundy’s kept woman and save her family, Sally gives her grounded materialist analysis of the limitations of conventional relationships, respectability and honesty in a world built on the grossly unequal distribution of power and wealth:

Them as is workin’ ain’t able t’ keep themselves, ne’er heed a wife. Luk at y’self . . . An luk at our Harry. On workhouse relief an’ ain’t even got a bed as he can call his own. Ah suppose Ah’d be fit t’ call y’ daughter if Ah was like that, an’ a tribe o’ kids like Mrs Cranford’s at me skirts . . .Well, can y’ get our Harry a job? I can an’ Ah’m not respectable . . .’ Hardcastle pointed to the front door: ‘Get out . . .’ he snarled. ‘Oh, Harry,’ his wife whimpered: ‘Oh, Harry,’ she gripped handfuls of the folds of her apron. ‘Right,’ replied Sally, defiantly: ‘Ah can do that, too. Ah can get a place o’ me own any time. Y’ kicked our Harry out because he got married an’ y’ kickin’ me out ’cause Ah ain’t . . . (pp. 246-247).

4. Critical Responses

Hans Fallada published some twenty-two works between 1920 and his death in 1947 (and in addition a number of novels have been published posthumously). Of those published in his lifetime, seven were published in English translations (five also made by Eric Sutton who translated Little Man What Now for Putnam). Fallada was harrassed intermittently by the Nazi Party after 1933, and Kleine Mann – was Nun was reissued only with extensive cuts and rewriting, but its author remained in Germany and mainly out of prison before he was bizarrely patronised by Goebbels who pressured him over several years between 1942 and 1944 to write an anti-semitic novel of Germany during and after the Weimar republic, including the ‘saving’ triumph of Nazism, a work which Fallada uncoincidentally did not get even near to completing. His last work completed just before his early death was in fact an anti-fascist novel about a couple who had resisted Nazism. (3) Not surprisingly given this career and the reputation of a number of his novels, Hans Fallada has a fairly large critical literature of his own, with critical articles in German and French and somewhat fewer in English. However, of most immediate relevance to this article is the fine critical essay which compares Fallada and Greenwood, so it is only proper to feed its comparative understanding of the two novels into this discussion. This is A.V. Subiotto’s book chapter ‘Kleiner Mann – was nun? and Love on the Dole: Two novels of the Depression’ from 1982. (4)

Subiotto starts by noting that,

Despite vast differences in their social backgrounds, a disparity of political enthusiasm, dissimilar methods of writing and literary traditions, and contrasting historical and economic situations that formed the context of their writing, these two novelists shared a burning thematic interest that transcended the diversity of their depictions . . . it is the central theme of depression and unemployment (p 77).

Subiotto sees, as I do, differences between the degree of pessimism and optimism in the two novels and he sees this as largely determined by the class-origins of the authors:

The contrast between the two writers is a matter of class. Greenwood was rooted in the working-class . . . Even when in work the wages were so mean that none could rise above the abrasive, interminable struggle for mere survival, as Larry Meath, Greenwood’s politically conscious and articulate ‘mouthpiece’ in Love on the Dole tries to impress on Sally Hardcastle, whom he would like to wed.

. . .

Fallada, on the other hand, belonged to the middle class, with its pretensions that were also its weaknesses, the major one – certainly uppermost since the astronomical inflation period of 1921-32 – being a consciousness of higher status than the the working-class when its actual power was at a nadir, measured in terms of savings (which had disappeared), solidarity (negligible in terms of trade union organisation) and security of employment (extremely vulnerable to the acceleration and rationalisation of business and commerce). This ‘false consciousness’, constantly nourished by the fear that the step downwards into the proletariat is the ultimate degradation, echoes through Kleiner Mann – was Nun? (pp.77-8).

Subiotto sees the characters of Love on the Dole in contrast as firmly proletarian – pointing for instance to Harry Hardcastle’s initial feeling that a lifetime spent working as at first an apprentice and then a qualified engineer in Marlowe’s works offers everything that a working-class man could want. This is a distinction in the focus of the two texts which Putnam clearly did not see as vital enough to consider publishing both novels. Subiotto and I are also completely agreed that while Greenwood gives us characters located in a community, Fallada focuses on dislocated individuals:

In contrast to the sense of fellowship in distress that pervades Love on the Dole, Fallada’s novel focuses on one person, the shop assistant Johannes Pinneberg, as he struggles to survive and maintain his family in an engulfing tide of rationalisation and redundancy. Where Greenwood gives us a network of interweaving lives, Fallada depicts an individual in a precarious and exposed relationship with his surroundings, isolated from any sense of community, restricted to his wife and child for companionship and warmth. Pinneberg has no past. (p.80)

Having said that, there is one Greenwood critic, Carole Snee, who has (I think in many ways rightly) argued that actually his representation of community in Love on the Dole has a surprising lack of depth, with an absence of grandparents in the Hardcastle family and others, and the complete absence of any family context at all for the working-class intellectual Larry Meath – another character with no past, or at least none represented in the novel itself. (5) This is in contrast to another retrospective Greenwood narration of Hanky Park in the thirties in his memoir There was a Time (Jonathan Cape, 1967), where a much richer and multi-generational community is lovingly portrayed. Nevertheless, there is a more extreme lack of community in Fallada’s novel – it is positively a feature of Pinneberg and Bunny’s lives (we do meet her parents and brother early on, so we have some context for her, but they are glad to see her go and do not re-enter the story at all thereafter, while Pinneberg and his mother are in effect estranged). Pinneberg ‘comes from nowhere and has nowhere to go’ (Subiotto, p.89).

Subiotto argues that Greenwood’s novel is the more explicitly political of the two, while Fallada’s political points are much more implicit – constructed only by the reader rather than by any character. He also suggests an important difference in the deployment of literary firm and genre:

The self-taught Greenwood applies orthodox patterns of narration but his searching indictment of the society he lives in bursts the outer structure of the novel at many points. Fallada, on the other hand, conforms to the norms of the popular novel: Piineberg is handled as a literary ‘hero’ with the consequential effects of this role on the novel – however ordinary or inconspicuous he may be in reality, he nevertheless becomes the focus of Kleiner Mann – was nun?, an individual picked out against the rest of society. The clichés of romance are employed to the same end: Lammchen [Bunny] and Pinneberg, like the great lovers of literature, escape finally into a private whole world of their own over which they have psychological control (p.89).

There are indeed many conventional features of literary narration and genre in Greenwood’s novel, including some related to nineteenth-century condition of England novels (such as Elizabeth Gaskell’s Mary Barton, 1848, and North and South, 1854), and some related to later Manchester School realism in plays, though I would not see these conventions as necessarily all that distinct from popular fiction modes in the first half of the twentieth century. Popular fiction is a large category, or label, of course, and not all work which can be included under the label works in the same way, though it is often broadly realist. Both more ‘literary’ and more popular fiction often use conventions likely to be already familiar to most readers, so that they are approachable and engaging reading experiences. Both Fallada and Greenwood’s novels have comic or tragi-comic elements which could be seen as aspects of this urge to engage readers (for example Bunny’s repeated failure to make an edible meal early on, and the shameless if concealed self-interest of the ‘chorus’ of older women in Love on the Dole, when they ‘oblige’, or ‘help’ their neighbours). One very broad assumption often made about popular fiction is that it favours ‘happy endings’ as part of the ‘readerly’ satisfaction it offers, which is not clearly the case for either of these novels. Little Man What Now ends on a note of apparent personal partial victory over material circumstance, but I cannot see it as a very convincing or enduring one given the novel’s clear portrayal of the economic and political contexts of early thirties Germany, which are constantly in the background of Pinneberg and Bunny’s apparently central relationship. Love on the Dole ends with an ironic happy ending in that Mr Hardcastle and Harry achieve their minimal but greatest wish, to be employed, but only at the cost of Sally’s surrender of her body and agency to Sam Grundy (though a short story sequel suggests she may escape through her own strength of character after a short period – see What Sally Did Next: Greenwood’s Sequel to Love on the Dole (‘Prodigal’s Return’, John Bull, January 1938) ).

Contemporary British responses to the two novels had some similarities (and indeed concur with some of the points made by Subiotto) seeing them particularly as foregrounding the ways in which current economic crisis endangered the most usual human relationships, making even a minimally ‘normal’ existence impossible for the poor and unemployed. The very positive and clear review of Fallada’s novel in the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer is fairly representative:

The story of a young German couple, a clerk and working-class girl, struggling for existence in almost impossible conditions. They are quite ordinary, young, not very intelligent, not very capable, helpless and inarticulate, but touchingly in love with each other. The girl is braver than the man; but both are brave, for what one sometimes fears is the most usual motive for courage – because they have to be. If they lose hold for a moment, they will go under, and they know it. It is this perpetual sense of danger that makes their story exciting throughout, a sordid. chronicle of petty misfortune — a marriage in secret because the boy will lose his job if It is known, a baby whose birth they have failed to avert, unemployment, degrading dependence, spasmodic help and neglect from public services, loss of respectability and self-respect, semi-starvation and nervous collapse. The soldier in the trenches was at least looked after and directed, if only as protective cannon-fodder, but there is no one and nothing to look after this pair of innocent grown-up children. If they die or disappear, nobody will notice. It is one of those stories that only need to stated, presented under the dry light of eternity, and it is so presented (‘Novels of the Week’ by Muriel Jaeger, 19 April 1933, p. 6).

A review of Greenwood’s novel in the same (important) regional newspaper though by a different reviewer raises some similar points about inescapable economic conditions and their effects on ordinary lives (though perhaps through nervousness about sexual matters it does not refer to Harry and Helen’s unplanned and unaffordable parenthood, nor to Sally’s ‘agreement’ with Sam Grundy):

Love on the Dole is one of those pitiful pictures of inevitable conditions and the dashing of young hopes that civilisation is breaking its head if not its heart over, in every city of the civilised world. The gay youngster who gets his first Job and draws his first wages, his development into the hopeful unemployed man, the less hopeful, the despairing and finally the more or less degenerate compulsory loafer – we know him well. We cannot help him. To read about him is so unspeakably saddening that even the denouement that Mr. Greenwood has chosen, to end our depression about his poor decent young Harry Hardcastle, comes as relief. The book is human and actual to the very highest degree, and the occasional bad English should not count against it (‘Novels of the Week’, review by Alice Herbert, 28 June 1933, p. 6).

This is the only review I know of which comments on the novel’s ‘occasional bad English’, and I am not certain whether this is about the odd awkwardness in Greenwood’s prose or about some aspects of his use of Salford dialect.

There are undoubtedly similarities between the two novels, despite as Subiotto says, their origins in different cultures and manifestations of global economic collapse. The politically aware characters in Greenwood’s novel of whom Larry Meath is the main focus, are all from the left, while the few politically committed named characters in Fallada’s novel are Nazis (the Communists being referred to but not named – of course Fallada will have been aware of the dangers in 1933 of paying them more attention). Fallada’s portrayal of an ‘ordinary’ man and woman who have little analytical grasp on the circumstances which dominate every aspect of their ruined lives is effective and engaging. Similarly, Greenwood’s representation of the way in which his politically aware character Larry Meath is unrepresentative of the Hanky Park community makes a related point. However, in the end I think (though I am no doubt always already biased) that Love on the Dole‘s representation of the iron reality of being as Harry says ‘economically up against a blank wall’ (Love on the Dole, p. 249) has a grim and explicit logic to it which may be more powerful that Fallada’s portrait of comi-tragic unawareness. But both Putnam and Cape made successes of of these two novels, and used their expertise to design and market them well, and thus to disseminate Fallada and Greenwood’s representations of the cycle of poverty, and to ensure their legacies.

NOTES

Note 1. Though the memoir is very precise about many things, it does not name any of Greenwood’s rejected typescripts – and indeed it curiously does not even name his accepted one, Love on the Dole, but assumes readers will know about his most successful novel. He had also been sending out short stories to magazine editors, and as referred to above I think he may also have sent out a short story collection which was perhaps an original version of Love on the Dole (though it too did not have that title, nor of course a central unifying plot, and did not include a number of what would become central characters in the final novel version). For my thinking and evidence underlying these suggestions see: Walter Greenwood: a Biography and Word and Image in Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s The Cleft Stick (1937).

Note 2. The German film, Kleiner Mann was nun? released in August 1933 was made under Nazi censorship and was disowned by Fallada during filming (director, Fritz Wendhausen, production by RN Filmproduktion). The US film Little Man What Now? was released in May 1934 (director Frank Borzage, production by Universal Pictures). It was critically well-received but not a box-office success (see the useful Wikipedia entries for the German and US films: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Man,_What_Now%3F_(1933_film)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Man,_What_Now%3F_(1934_film) ).

Note 3. Pryse has a useful Wikipedia entry – see https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerald_Spencer_Pryse.

Note 4. There is a fine life of Fallada by Jenny Williams: More Lives Than One: a Biography of Hans Fallada, 1998, and reprinted by Penguin in 2012. For an introduction see Fallada’s Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Fallada .

Note 5. In Weimar Germany: Writers and Politics, edited by A.F. Bance, Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh, 1982, pp. 77-89.

Note 5. In her book chapter ‘Working-class Literature or Proletarian Writing’ in Culture and Crisis in Britain in the Thirties, edited by Jon Clark, Margot Heinemann, David Margolies and Carole Snee, Lawrence and Wishart, London, 1979, pp. 165-191. I discuss her stimulating critique of the novel in Walter Greenwood: Love on the Dole: Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, 2018, mainly on pp. 52-54.