In Greenwood’s 1967 memoir, There Was a Time (p.123), he recalls that during the international crisis of the First World War he felt a more individual but nevertheless acute personal crisis:

There was the other war, the one within me. In this the possibility of a truce was out of the question . . . All that I was certain of was that imprisonment in an office for the rest of my days would be insufferable . . . the abomination of the high stool and desk . . . and servitude at the desk became intolerable (p. 123).

In fact, as we shall see, Greenwood’s intense dislike of being a clerk echoed across his life and work, from early memories to early stories, to first novel, to documentary, to a mid-life crisis (perhaps), to final memoir. Our starting point above dates from when he worked at the Pendleton Co-operative Society Offices, probably between 1917 and 1920 (though it is here recalled in the mid-nineteen-sixties). However, even in 1915 he had been a boy-clerk aged twelve in a pawn-shop before leaving school at thirteen in 1916, and then worked at the same pawn-shop full-time probably until he was fourteen. This experience is reflected in the novel of Love on the Dole where the school-boy clerk Harry Hardcastle reflects gloomily on his fate, all brought about, he thinks, by the ‘fair handwriting’ he has achieved despite his poor schooling:

Three years now he’d been tied up there; three years before school hours and after; three years he’d sat in that dark corner of the pledge office writing out millions of pawn-tickets. Damned in a fair handwriting: ‘See our Harry’s handwriting. By gum, think o’ that, now, for one of his years.’ He had paid dearly for those flattering remarks. And now, if his parents were to have their way he was to be penalized even further; they wanted him to be a scrivener for the rest of his life. They would do. ‘Well, Ah’m not doin’ it,’ he muttered, aloud (p.17, Kindle edition, Random House).

As so often in Greenwood’s writing about clerks, there is the fear of imprisonment indoors (related to his love of the outdoors and the natural world), and of it being a life-long sentence once entered upon. The word ‘clerk’ is used thirty-one times in the novel of Love on the Dole so it is of some importance, but it is also noticeable that those for whom clerking is an occupation are found on two sides of a sharp dividing line: those who are blessed by their employment in Labour Exchanges are in a different (if only relatively different) world from their clients. Thus there are those clerks whom unemployment keeps employed:

An L-shaped counter ran the length of two sides behind which clerks sat at tables or searched filing cabinets for documents. Here and there, at regular intervals, more clerks sat to the counter attending to the new claimants (p.17).

And then there are those who ‘out of harness’ seem obviously, and despite their dress codes, to be plainly blue-collar workers rather than white-collar workers, and really in effect working-class:

[Harry’s] gaze wandered; was attracted by a constant procession of men visiting one part of the counter marked: ‘Situations Vacant’. Engineers in overalls, joiners and painters and clerks in seedy suits; stevedores, navvies and labourers in corduroys. They came singly and in couples, stood in front of the taciturn clerk, offered their unemployment cards, received answer by way of a shake of the head, turned on their heels and went out again without speaking (p.16).

In truth, as the novel points out by juxtaposing the two groups with the same title of clerk, they are in reality close kin, separated only by economic chance.

At the pawnshop Walter suffered the ‘endlessness’ of fifteen-hour weekdays (There was a Time, p.108) before his mother objected strongly to his catching lice from the pledged clothing (said to have become much more common with the home-leaves of troops from the trenches). She helped Walter get the much better job at the Pendleton Co-op building as ‘an office boy in the General Offices and at three times his present wages’ (p.109). His mother’s neighbour and friend said ‘Ten shillings a week and a job for life . . . what a lucky lad he is’.

Image from a 2008 photograph by Richerman, when clearly the Grade II listed but disused building was out to let (photograph reproduced and edited from Wikidata under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported Licence: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pendleton_Co-op.jpg). Building designed by F. Smith and opened in 1887, with a 1903 extension by W.H. Walsingham. It housed both offices and shops, as well as the dairy of which Greenwood’s one-time fiancée Alice Myles became manageress. For further details of the building see the Historic England entry: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1386097?section=official-list-entry

Had he been ‘a dutiful son’, Walter would have appreciated this opening and, though he agreed it was an improvement on the pawn-shop, he had begged his mother to let him try for a proper job with his hands (engineering, carpentry, cabinet-making) – anything if unlike at the Co-op he got Saturday afternoon off to go out with the other lads. She was adamant: ‘It is a clean job you’ve got and you’ll wear a collar and tie. There’s a week’s holiday remember, and no short time’ (p.110). Hence his ‘servitude at the desk’:

Ledgers, ledgers, ledgers. The staring regiment of them mocked my impotence. Of the whole boiling only one had interest for me, and in letters of gold on its spine were the words STUD BOOK. Within were the names and particulars of every horse owned by the Co-op. My heart was with all this stood for, the out o’ doors and, preferably, miles from Salford where fields were green and where, if you put your hand on a tree trunk, your palm was not sullied by soot. Oh, dreams, dreams’ (p.128).

In due course Walter’s mother ‘received a letter from the Society’s secretary’:

Would she please call upon him. In the privacy of his office, with stern maternal eyes upon me, I was carpeted. On the Secretary’s desk were a number of account books and registers of the Society’s membership each open at pages which I had decorated with pencil drawings of horses. It was my own fault, they ought to have been erased (p.128).

This is a piece of dead-pan telling typical of Greenwood’s narrative technique in There Was a Time: we have to read through something of the detail of the Co-operative Society’s clerkly administration before we get any clue of exactly what Walter’s misdemeanour has been – drawing horses on the sacred account books and registers. Then comes as a kind of punch-line the boy’s admission of guilt which is nothing of the sort – if only he’d erased the sketches he’d never have been caught. I have no doubt that the Secretary’s charge is not just about the decoration of the documents but also about the clear record they give that there have been times during paid hours when Greenwood has not really been spending his energies on the mutually beneficial social mission of Co-operative business! Indeed, as another page in the memoir recalls, this was not Walter’s only misuse of office routine:

One of my jobs in the office was the responsibility of the outgoing post, the recording of every charge and the purchase of the necessary stamps. Twice daily, morning and afternoon, I had the pleasure of walking to the post office and wasting as much time as I dared on the way back (p.130).

On these daily instances of transgression, he does not merely draw horses but instead makes active efforts to get in touch with chance-met Manchester patriarchs who still take their daytime exercise on horseback at this period.

When he gets home from work on that official reprimand day the boy-clerk’s scolding continues from his mother. However, eventually two friendly neighbours, Polly Mytton and Mrs Boarder, persuade Mrs Greenwood to let Walter go and work with horses if he must. He calls on the house at Swinton of a horse-riding cotton-spinning gentleman he has met during the post-office run and is indeed engaged as a stable-boy. His mother exclaims, ‘What next?’ (p.131). When Walter moves to live in the stables, the groom says he must be crazy leaving an office job to work with horses seven days a week. Greenwood tells himself silently that the groom could know nothing about ‘the torture of imprisonment in offices’ (p,134). His period working with horses is not all blissful nor is it easy work (his initial total ignorance of horses and how to ride is a handicap, as it were) and many of those he meets in the world of horses are rough or in some cases positively vicious, where they are not outrageously exploited juniors, including stable lads and jockeys. It is also a world which is fading: his horse-riding gentleman has already reduced his stables and bought two motor-cars, and his ex-head-groom-now-chauffeur is persuading his employer to try driving lessons. However, Greenwood expresses some further ambition by getting a new job at a racing stables owned by an investor. In the end it is economy as much as technology which brings Greenwood’s (rough) pastoral to an end: ‘the post-war boom was beginning to crack . . . the north-country speculator was in financial difficulties . . . and his string of horses had to be sold’ (p.157).

Greenwood returned home not to an office-job, but to manual work – if hardly of the skilled kind he had earlier wished for. His childhood friend Nobby, out of the post-1918 Army, has set up an exploitative business (BOXO Co.) which repairs damaged wooden tea-crates for reuse and delivers them with two cheaply acquired ex-Army lorries. The workers, including Greenwood, are paid piece-rates and all suffer constantly with infected cuts to their fingers from removing the rusty nails. Even here Walter’s clerical skills are taken for granted: ‘And you can type the letters and be my sekertary when I want you’ (pp.161-2). Nobby anyway soon sells the business on – on a largely fraudulent basis to a patently alcoholic businessman who drives the workers away by lowering the piece-rate to a level even these poor men cannot subsist on.

Next Walter gets a job as an assistant in a large wholesale warehouse, ‘Messrs Battersby & Co Ltd’ (not its real name which I have not yet identified), where he works in the ‘Carpet and Furniture Department’. So it is not an office job – he tells a Labour Party friend that he is now a member of the ‘Shop Assistants’ Union’ (p.174). Working conditions at Battersby’s are clearly not good, but Greenwood, perhaps because the job involves handling physical objects, seems to detest them much less than ‘clerking’. However, after 1927 the Depression begins to bite and soon Greenwood’s services are dispensed with. He has to sign on the dole, and has at least the more satisfying experience of taking on a less alienated kind of clerking, or perhaps even the start of his vocation as a writer, for his activist friend James Moleyns’s local Labour Party news-sheet:

‘There’s a job for you . . . typing. There’s the stencils . . . [and] here’s my pieces . . . aye, and we don’t want it to be all tub-thumping. Bit of variety, that’s what’s needed. Humorous column. Try your hand at that’ (p. 185).

Perhaps Greenwood’s later literary-political style was influenced by this early advice?

In an occurrence of a kind which is never recorded in Love on the Dole, Greenwood is offered a vacancy by the Labour Exchange:

‘You a touch typist?’ The dole clerk’s tone was abrupt.

I said ‘yes’, without knowing what ‘touch typist’ meant.

‘There you are. Motor Works. Trafford Park’, he said, adding warningly, ‘It’s temporary’ (p.188).

The job, which was in fact at the Ford works, does not last long but in it Greenwood learns of a new style of what he saw as total servitude:

When an employee of the Motor Works passed through the works’ gates to the clocking-on machines he stepped from Britain into Detroit, where Moloch, in the shape of the Main Line Assembly, held unrelenting sway (p.189)

The Trafford Works was in fact the first assembly line in Britain, and had started rolling in 1914. Greenwood does not work on the assembly line, but the clerks too must fit into the system: they copy and constantly update records of components:

Each vehicle in the catalogue was anatomized down to its smallest screw, a drawing made of every part and its dimensions minutely described and numbered. These were put away in long rows of filing cabinets so cunningly arranged as to place the filing clerks perpetually under the watchful eye of the office manager on his raised desk (p.189).

Greenwood’s understanding of modern (alienated) labour, and its disciplinary supervision, is very clear here. Indeed he recalled this particular employment with an explicit anger (as opposed to his usual deep underlying indignation) some six years later in the ‘Author’s Preface’ to his and Arthur Wragg’s short story collection:

As bookkeeper-correspondence-clerk-typist (all three jobs often rolled into one) . . . I never earned more than thirty-five shillings a week with one exception. This was in 1931 . . . when Mr Henry Ford’s establishment paid me ninety shillings a week for a few months. – which was the last attempt of commercialism to entrap me. The ninety shillings, however, was too small a bribe for me to relinquish my manhood and have it submerged in Mr Frederick Taylor Winslow’s ideas of Mass Production Efficiency. I declined to sell myself, to smother my individuality when I punched the time-clock, to cease being Walter Greenwood when the time-clock’s bell rang and changed me into number 2510 or whatever number I was.

By the time I had reached my late teens the myth of the ‘honest working man’ had ceased to impose on me . . . the sooner I eschewed ‘honest toil’ the better it would be for me and my immortal soul, for my prospects were that, had I surrendered, I should have landed myself on a clerk’s stool at thirty-five shillings a week for the rest of my life.

So . . . [I] taught myself how to write for no other reasons than that the writer’s profession paid more money than clerking (if you wrote the right kind of stuff and were lucky) (The Cleft Stick, 1937, pp 8 and 7).

Greenwood’s experience of Ford at Trafford Park must have been in the late nineteen-twenties when it was producing some six thousand cars each year for the UK market, before increased production fully switched to Dagenham near London in October 1931. From 1927 to 1931 the Trafford Park Works produced the newly introduced Ford Model A, which in fact proved rather expensive for British motorists because its relatively large engine incurred additional taxes in Britain (the Ford Model Y introduced in 1932 was in contrast a better seller – though still obviously beyond the pocket of most working men – even if it was the only car then on sale which cost as little as exactly £100 new).

Remarkably, there is a surviving 14 minute film of the Ford Model A assembly line at Trafford Park at work in 1929 on YouTube, curated by the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu. Below there is a one-minute clip from the film of engine assembly – the film naturally, being filmed by and for Ford, takes a more technocentric and assembly-line admiring view than does Greenwood with his humanistic or perhaps socialist critique: https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxLMbS6yiYMy-bFf3BEnvQmnDReiuQ8aMM?si=AXXSh7OiSR57-BKu (for further information about Ford in Britain in this period see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ford_Trafford_Park_Factory and https://www.britainbycar.co.uk/trafford-park/341-ford-motor-co-ltd.)

Greenwood acknowledges that Ford paid much better than British firms – but at what cost? The loss of your individual and immortal soul? Whether under modern business methods at ninety shillings or old-fashioned British methods at thirty-five shillings, ‘clerking’ clearly felt like a life-denying plod to Greenwood – and perhaps indeed it represented the very opposite of what he meant by ‘writing’. Not only that, but it was likely a life-long fate with little prospect of advancement or escape. Greenwood’s final condition here for surviving as a writer (the ‘right kind of stuff ‘ and luck) was in fact not met by his own writing for some several years between 1928 and 1932, during which he had just one story accepted by the monthly Storyteller Magazine (”A Maker of Books’) in 1931. The editor in that year was Clarence Winchester (1895-1981), who edited a range of magazines for Amalgamated Press which had taken over The Storyteller from Cassell & Co in 1927 (under their ownership between 1907 and 1927 it had been slightly differently titled as The Story-teller (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Story-Teller). Winchester was chief editor for many part-works on railways, aviation and ships, but he also had great experience as a fiction editor and wrote a number of popular novels and some short story collections, though mainly in the nineteen-forties. The Bear Alley website devoted to magazines, comics and popular fiction gives a very helpful overview of Winchester’s career (see https://bearalley.blogspot.com/2014/11/clarence-winchester.html). Clearly, Winchester was convinced by the quality of Greenwood’s ‘The Maker of Books’.

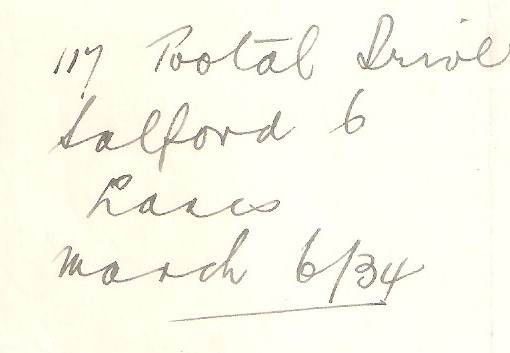

Though that was the first (and most important) step in a journey which enabled him to achieve the unlikely goal of becoming a full-time writer rather than full-time clerk for the rest of his life – an achievement which he felt great satisfaction in, as his volumes of press clippings witness: Walter Greenwood’s Press Cuttings Books (1933-1974) *. It was not, though, the end of the author’s engagement with the life of the clerk, which plainly lived on in his mind as what dreadfully might have been his fate. And, indeed, between Ford Trafford Park and before literary success there was a further spell as another kind of clerk/typist – one who worked for what turned out to be con-artists. While on the dole and despite his 1937 account of deliberately withdrawing from the labour market, Greenwood tried hard to get a job. As he recalls in There was a Time, he went to the public library where at stand-up desks the ‘Situations Vacant’ pages of newspapers were pinned up. Here, ‘down-at heel-clerks, salesmen, commercial travellers and others wrote down the box numbers and particulars of whatever jobs were being offered’ (p.195). Greenwood quotes what seems to be half an example of his own job applications from this time and half a parody of the genre:

Dear Sirs,

With reference to your advertisement under Box number . . . My qualifications are several years’ experience as salesman, double-entry book-keeping and typing. I am quick and accurate at figures and am capable of dealing with correspondence. I have satisfactory testimonials, am twenty-six years of age and suggest a wage of . . . (p.195).

The sample application (which from his given age must date from 1929) breaks off there, as Greenwood ponders how much to ask for – what can he actually survive on, what will be low enough not to make them reject him out of hand? On this occasion he receives a reply from ‘Suite 39’, the base of a Manchester company of ‘Estate and Transfer Agents and Valuers’. At interview it is made clear to him that he should ask no questions but write letters not necessarily exactly in his own persona aimed at driving down even further the purchase costs of already failing small shops and businesses. He is paid ‘to start with’ the weekly wage of twenty shillings (three shillings less than his dole), except that after a short period and news of the 1929 Wall Street Crash, there are some delays to his pay. As a matter of fact, though I have read Greenwood’s account of the fraudulent business many times, I cannot see that the two company partners actually successfully defraud anyone because they fail either to buy or sell a single business. Not surprisingly, the two soon disappear without leaving forwarding addresses. The ‘three weeks pay in time for Christmas’ (p.199) which Greenwood has been promised never does turn up. Greenwood goes home penniless on Christmas Eve. However, he took what compensation he could:

I went round the corner to Messrs Battersby’s packing and forwarding department where an old acquaintance gave me a couple of large sheets of brown paper and some string. As the Manchester Town Hall clock struck the hour which brought the business of the day to an end I retrieved my unstamped insurance cards, made a parcel of the typewriter, took it outside, locked the office door and put the key through the letter box, then lugged my stolen burden home (p.199).

The unstamped insurance cards mean that this period of employment will not even improve his eligibility for unemployment benefit. However, this literal departure from an office also marks a deeper transition for Greenwood: it is his (well, almost, as it turns out) farewell to clerking as he turns the typewriter over to his desired occupation of writing (in fact he seems still to have written story drafts in pen in manuscript before typing them up to send off to magazines and publishers).

It does not prove an easy conversion: ‘My discouraging and growing pile of rejected manuscripts had one positive quality – the undeniable proof of practice’ (p. 209). Eventually, he receives the letter from the Editor of The Storyteller magazine saying that he would ‘like to have your story “A Maker of Books” for publication and [to] offer twenty-five guineas for the first British serial rights . . . [ellipses sic]’ (p.214):

Twenty-six pounds five shillings! A pound a week for half a year. A pound, the equivalent for a week’s work at detestable clerking and two shillings a week more than unemployment pay, not to mention the delight of so congenial an occupation. It needed time to digest.

No one ever did take up the serial rights. Even in this moment of triumph Greenwood does not forget the baseline dread of ‘clerking’. It is no coincidence that his first published story is about someone who ‘makes books’, even though it is about betting rather than literary creation. Greenwood sees the two as having kinship partly because of the co-incidental overlap of language but more substantially because for a working-man both are forms of gambling on the very unlikely. When first sitting down to write, he had a sudden memory of a work-mate (and in fact a fellow clerk) who thought becoming an illegal bookie would save him:

Out of nowhere came the recollection of Sandy Sinclair and his consuming hatred of the Motor Works’ factory environment . . . in his way was he not like me basically, in pursuit of the same thing, searching, like so many, for a way out of intolerable conditions? His desire was to make a book, mine to write one. ‘A Maker of Books’, there’s the title anyway. All I had to do now was to write the story (p.205).

However, one win on the gee-gees does not generally make you for life: after his Story-Teller success his luck seemed to run thin, though his gambler’s hope does not altogether:

For me there was the sustaining and unquenchable hope of another windfall, despite the discouraging and persistent rejection of the stories I was sending the rounds. Instead of the puffed-up and fatuous dream of selling two a month I was reduced to the threadbare hope of placing two a year . . . But what had reality to offer by way of an alternative? The prison of an office job, if one could be landed at twenty shillings a week? No, let the newspapers shout ‘workshy’ (p.223).

However, he did get the lucky break he needed and clearly had written the ‘right stuff’ when his novel Love on the Dole (partly based on a radical rewriting of a number of his short stories) was accepted by Jonathan Cape in 1932.

Nevertheless, he revisited the physical and mental life of the clerk twice more in his writing before his memoir – once in a short story written between 1928 and 1931, and once in his documentary work of 1939, How the Other Man Lives. Chapter II of the latter is titled, like the other chapters, by a simple occupational title ‘The Clerk’, and is based on an interview with a clerk in Manchester. In each of the thirty-seven chapters in the book, Greenwood shows great empathy with his interviewees, but this account of the clerk’s work and life plainly had special echoes for Greenwood:

He told me that he had been working for his present employer for nearly ten years. Since leaving school at fourteen this had been his one and only job. At that age he had started as an office boy for a wage of seven shillings and sixpence a week . . . The family jubilantly described his luck at having secured a ‘job for life’ (pp.16 -17).

The last phrase of course exactly recalls that used by neighbours of Greenwood’s Co-op job in There was a Time. The witness tell him that he continued studying at night-school, so that he is well-versed in book-keeping, shorthand and typing. He has now after seven years at the firm been promoted to the rank of ‘a fully-fledged ledger clerk’, but does not expect promotion beyond that at any point. Greenwood wins his informant’s confidence because he shows his familiarity with his life:

The clerk’s surprise that anybody could possibly be interested in him was painful. He was embarrassed until he found that I could talk of half-yearly balances [and] the monthly grind of the sending of statements’ (p.16).

Greenwood can also see that there is a necessary inner and alternative life,

of dreams of high adventure in lands beyond the seas. The latter was not guesswork for stuffed in the clerk’s gaping pocket was a boy’s thriller magazine, the kind that tells of the doings of men of muscle’ (p.16)

The clerk says he likes reading and best likes books about ‘the sea and foreign countries’ – and similar kinds of films too, though he says his girl best likes romances and films which show ‘the latest fashions’ (sadly, exactly in line with expected gender-stereotypes of the time, these kinds of films give him ‘the hump’) (p.18). The young man also echoes Greenwood’s own earlier desire to be a craftsman, to actually make things. He wanted to be apprenticed as a joiner or cabinet-maker, but his father, a qualified engineer, thought there was no security in having a trade these days. Nevertheless, he still likes films about what he thinks of as real productivity: ‘I like to see men building things, like in that film called Boulder Dam‘ (not as it might at first appear a documentary but a feature film directed by Frank McDonald and produced by Warner Brothers in 1936 – see the brief IMDB entry https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0027391/?ref_=ttpl_ov).

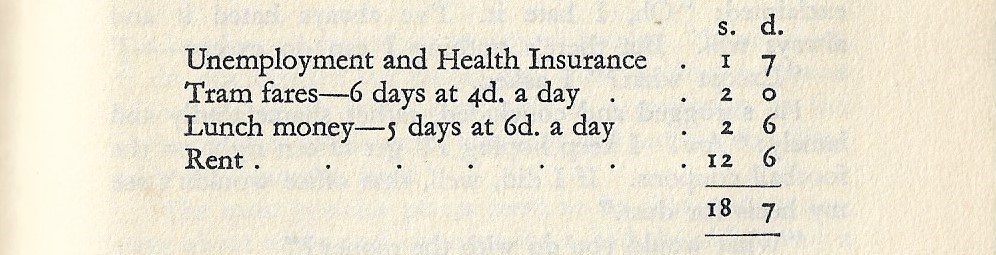

The young man plans to marry his young woman, but they are both aware that really his wages are barely adequate and will only keep them if both continue working and do not (given the maternity support conditions of the time) have children. Greenwood discusses the economics of the young man’s life, which are clearly all too familiar to him from his own past. In a positively documentary manner which might equally come from some of Orwell’s texts, he gives a breakdown of income and expenditure if the couple did have a child and they had to live solely on a clerk’s income:

This is what the clerk would absolutely have to spend from his wages to keep himself at work, and Greenwood concludes that this would leave only twenty-one shillings for clothes and food for two adults and a child, without taking into account ‘amusements’ (in which in line with expectations at the time, and indeed his own, being a life-long smoker, he includes cigarettes).

Greenwood asks the clerk if he is in a trade union, and the young man replies that he didn’t know there was any union clerks could join. He says no one in the firm is a union member. Instead, and somewhat like Harry in Love on the Dole the clerk pins his dreams on a lucky bet: ‘I keep hoping I’ll get fifteen right on the football coupons’ (p.22). Unlike Harry though, he would not blow his winnings on a holiday – his girlfriend would like to start her own business. Greenwood leaves the reader with a visual image of his witness which he sees as a physical occupational marker: ‘we shook hands and off he went – a scraggy figure, his shoulders falling into that stoop which already was permanent’ (p.22). While Greenwood expresses through objective observation his deep sympathy for the clerk’s life – and for the lives of all clerks – he also makes clear his continuing memories of the existence to which such a commonly-led life leads.

There is one more Greenwood piece of fiction about a clerk to consider – and I think it is one of his best short stories – but before that I would like to report the author’s painful and compulsory late re-experience of the trade of clerk, aged 40. Greenwood records in a letter to the BBC Radio Head of Drama, Val Gielgud, dated 3 September 1943, that just as he was about to finish the final draft of his wartime novel Something in My Heart, he had been called-up for Army service (though he is now getting someone else to type up the draft). This call-up for National Service of course was not wholly unexpected – he had been in the age range for call-up since conscription began in 1939, and by 1943 there was a considerable ‘manpower’ shortage (though better described as a person-power shortage since women were also subject to call-up and direction of labour, and indeed considerable efforts were made in that year to increase recruitment to the ATS, the Auxiliary Territorial Service or women’s branch of the Army). The letter to Gielgud, with whom he was friendly and often in correspondence about possible radio adaptations of his works, was headed with Greenwood’s Army Service Number (a unique identifier issued to every serviceman and servicewoman) as well as his current unit and posting:

14653657 Pr[iva]te Walter Greenwood, Basic Course 400, X Co[mpan]y, 12 TB [training battalion] (clerks) RASC, Buller Barracks, Aldershot. (1)

There is further correspondence too about whether the BBC might serialise Greenwood’s only wartime novel, Something in My Heart, which in the end they decided not to, partly because they felt it could have been more economically written and, reading between the lines, because there were political sensitivities – would such a serial look like endorsement of proposed post-war Labour Party social policy and run counter to BBC political neutrality? (See Walter Greenwood’s Wartime Novel: Something in My Heart (1944) and in terms of his view of war-aims his related newspaper article Walter Greenwood’s People’s War Manifesto (Sunday Mirror, 1941)).

Thus by an unfortunate irony, Greenwood was sent after call-up to be trained in the Army trade of clerk – the very occupation he had made it his life’s business to escape and to replace with something he found more creative and satisfying. His letter displaying his newly taken up Army identity is packed full of information, but perhaps now needs some decoding. The RASC was the Royal Army Service Corps, founded as the Army Service Corps in 1888, and granted the title Royal in 1918 in recognition of its service in the First World War. It was based at Aldershot Military Garrison in the nineteenth-century Buller Barracks (built 1890, in use by the RASC and its successor Corps till 1965, when a new Buller Barracks was built, which was in turn demolished in 2013). The RASC was responsible for transport and supply, which perhaps not predictably also included providing several kinds of clerical support, including to all Headquarters units. (2) I have not so far found a 1943 RASC Training Manual for Clerks, (though there must surely have been one), so do not know exactly what kind of training Greenwood underwent, and how it might have compared to his previous experience of ‘clerking’. His army records show that he passed his Army ‘Class III Trade Test for Learner Clerks’ (B200B form), but I do not as yet know what skills and knowledge that covered. Like everyone else, Greenwood will have done his basic or initial training in the General Service Corps, but once allocated to a more specialised Corps would have put up on his battledress its cloth shoulder-flashes, or much less likely by 1943 given demand for metal, brass shoulder-badges, in his case those of the RASC in the WW2 styles below (examples – alas not Greenwood’s as far as I know – photographed from items in the Author’s collection)

In any event, Greenwood was never posted out to an RASC unit as a clerk because, as his Army records also show, some twenty days after writing to Gielgud he was admitted to a hospital in Surrey with some form of serious psychological illness and remained there for more than twenty-one days. This led to his medical discharge from the Army that month, and the judgement that he was ‘unfit’ for any further form of military service (though he seems subsequently to have served in the Home Guard). (3) On January 15 1944 Greenwood wrote to Arthur Wragg about his recent experiences in terms suggesting he had suffered considerable psychological stress from a number of sources, not all a result of Army service, and not all clearly identified:

for myself I’m slowly emerging from a collapse of nerves – this was a culmination of bombings, other unhappy things and finally the last straw – the army. I had just signed a contract to make a film of The Secret Kingdom when my calling-up papers arrived. It appeared that a youngster in the film company’s offices ‘forgot’ to make the necessary application for my deferral (4).

Greenwood and his wife’s Ebury Street studio had been hit in the 1941 London Blitz, and Pearl had been injured, perhaps seriously, but this sounds as if it might have been hit again in more recent attacks. Pearl and Walter had quietly divorced in 1944, so this might well be another unnamed unhappy ‘thing’ to which he is referring (it is possible they had been living apart since her injury in 1941, since there is a reference in a letter from Edith Sitwell to Pearl being got safely away from London to her father, who, I think, probably lived in the US, where Pearl herself lived until her marriage). Greenwood’s letter to Wragg suggests that another thing he found traumatic was doing his initial training as (generically-speaking) an infantryman, as everyone serving in the Army did (this included looking after personal equipment and uniform, drill, basic weapons handling, and, if implicitly, internalising all the ways of the Army). He did this basic training at Maryhill Barracks in Glasgow.

Surrounding the barracks Greenwood saw working-class living conditions which seemed distressingly unchanged from those he experienced in childhood:

We were trained in Glasgow in the midst of slums so foul that it was difficult for me not to believe that I was a little boy of five miraculously projected into the future at the age of forty while still having to live in the slums as I knew them at that age. Glasgow is unbelievable – I mean in the way of life of the people. Ragged kids outside pubs, drunkenness abounding, I wake still with awful dreams teasing my sanity. (5)

Generally, Greenwood is very reserved when it comes to his own emotions and internal state, so this is a remarkable letter of personal revelation of trauma. The stressors he refers to here all come before his more specialised training at Aldershot in the Army trade of clerk, and clearly include a sense that he has been taken back in time to before he escaped from Hanky Park through writing. Nevertheless, I can hardly believe that being fated to spend the rest of the duration as a clerk will have lifted his mood – and the breakdown came during the training in the knowledge and skills necessary for an Army Clerk, so it seems reasonable to think this might also have been a factor in his illness. Indeed, this too might have seemed like a return to an earlier phase of his life – when he might have seemed destined to remain a clerk for life and when dreams of authorship and success were just that.

As I have briefly commented in my Biographical Timeline for Greenwood on this site, compelling the author to retrieve his clerkly occupation hardly seems the best use for the potential war-effort of the writer of such two evident and well-received People’s War texts as the film Love on the Dole and the novel Something in My Heart. Both had considerable impact on morale and understanding of the (potential) meaning and aim of the War, if newspaper reviews are any guide (see the entry for 1943: Walter Greenwood’s Biographical Timeline *). There is the further irony that deferral of his Army service was achievable because he was working on a recognised film project but was missed through the clerical error of an office junior (though given Greenwood’s own attitudes as a junior clerk, perhaps time had its revenges?). After October 1943 he was, however, able to return to film-making and writing, as well as Home-Guard duties.

Finally in this treatment of Greenwood’s engagement with clerical work is one of his earliest stories dating to the period of his unemployment between 1928 and 1931. I think it is one of his best short stories. It is the least obviously autobiographical of his writings about clerks, though it too has a focus on the potential satisfaction of labour and the actual alienation produced by its context, as well as on the physical and mental habits to which Greenwood saw the clerkly life leading. Though written some seven to nine years earlier, the story was first published in 1937 in Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s illustrated collection The Cleft Stick (Selwyn & Blount, London) and was titled ‘A Quiet Life’. It is about the work and life of a clerk called Stephen Wain, who becomes accidentally a specialist in ‘deed writing and engrossing’ at a Law Stationers after applying for a job the advert for which uses exactly those terms: ‘Wanted. Young Man for deed writing and engrossing’ (p.163). The first of these two legal terms refers, as the Encyclopaedia Britannica put it in 1910, to ‘any instrument in writing for declaring or justifying the truth of a bargain or transaction: as “I deliver this as my act and deed” ‘ (given by OED as a example of usage of the legal phrase and formula ‘act and deed’). The form of such a ‘deed’ gives it a legal force beyond a mere statement. The second term refers to what OED gives in its second definition of the word as ‘the action of writing out a document in a fair or legal character’. In origin, the verb ‘engross’ referred to the writing of text in large letters, as in the OED definition I.1.a : ‘to write in large letters, and now almost exclusively, to write in a peculiar character appropriate to legal documents; hence to write out or express in legal form’. Stephen has gained his post aged eighteen and clearly has no specialised legal education or knowledge, and indeed his job from then on is precisely writing out by hand legal documents in a ‘fair’ and ‘legal’ form. It is his handwriting which mainly gets him this ‘job for life’:

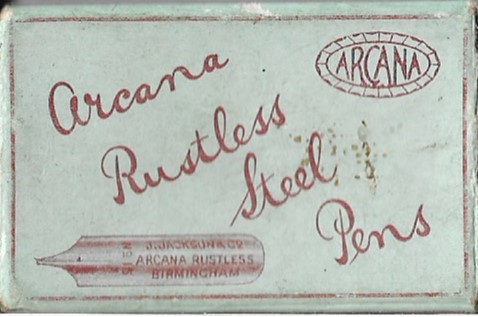

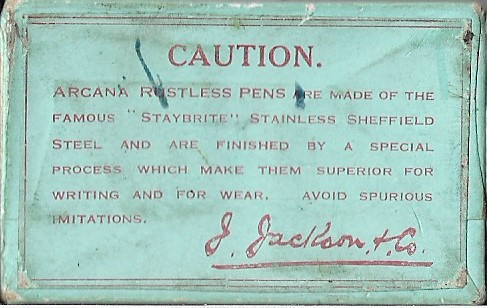

Stephen put in an application written in perfect copperplate. On its testimony and a letter from the vicar of the parish church, Stephen was engaged and installed in the room on the second floor back. Mr Blore made it clear, of course, that Stephen was to provide his own pens. From that day onwards Stephen spent most of his waking life writing deeds upon parchments, or lettering and illuminating addresses and testimonials from civic bodies and other organisations to all manner of scoundrels who had managed to acquire fortunes out of the misery of their fellow-men (pp.163-4).

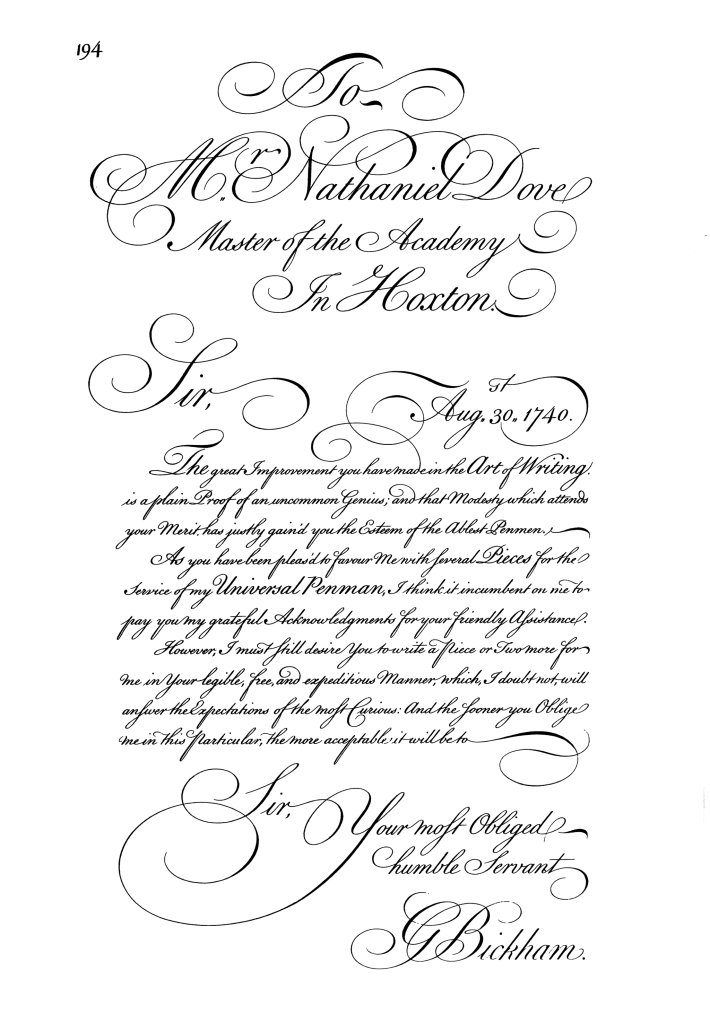

This description of Stephen’s work corresponds quite exactly with the OED definition of the function of a ‘Law Stationer’, though of course the comment on ‘scoundrels’ and the association of civic and business success with exploitation is evidently very much Greenwood’s rather than Stephen’s perception. The OED gives only two examples of usage of the term, one from 1836 and one from 1851, suggesting that the business of law stationer is firmly to be located in the nineteenth-century, and may be subsequently little practised. Copperplate was a handwriting style especially associated with Britain, and defined in OED meaning 4 as ‘a careful style of handwriting’. It descended from seventeenth-century forms of script called ’roundhand’ and was especially associated with the writing-master George Bickham (1683- 1758), who published an influential book of engraved examples of the scripts practiced by the best British calligraphers of his time. These forms of writing were made more practicable and more decorative by the invention of the metal nib (at first handmade in Britain in the 17th century and then mass-produced from the early 19th century), which replaced the older feather quill pens.

Copperplate was taught widely in schools in the nineteenth and early twentieth century through the use of copybooks which provided model scripts to be copied, and was the script considered ideal and essential for commercial uses. Thus a 1954 study of handwriting in Britain cited in OED said that British copperplate had been considered an ideal model for use in counting houses all over Europe in the nineteenth century. Copperplate was curiously something taught in the Elementary Schools attended by working-class children, but also considered an embodiment of elegant style and also ideal for use by book-keepers and clerks (though the only reference to handwriting in Greenwood’s essay ‘the Old School’ is his memory is that in infant school ‘we practised handwriting on trays of sand’, The Cleft Stick, p. 214). Greenwood’s writing is perhaps not classic copperplate but it is admirably legible in all the examples of his hand which I have seen (a boon for a scholar), and I think one can see its probable origins in scripts taught at schools in this period and expected to be useful for employment:

Along with the pens which Stephen Wain must provide there would have been some metal nibs suitable for general copperplate, as well as some specialist ‘engrossing nibs’ needed for the most decorative kinds of handwriting, as used in ‘addresses and testimonials’.

The story tells us through the testimony of Stephen’s pen-box both when he joined the Law Stationer’s and of his attitude to his work. Often after returning from his cheap lunch Stephen reflects positively on his ‘job for life’:

He sometimes said to himself as he hung up his hat and seated himself at his desk: ‘Ah I’m glad I work alone. I’m very fortunate, very fortunate indeed’. Then, pursing his lips, he would open the drawer of his desk and take out the box in which he kept his pens. There was an oblong strip of parchment fixed to the top of the box on which was written, in beautiful copperplate and with rubricated capitals:

‘Stephen Wain’s Pens. July 1882.’

What pleasure there was in selecting one , examining the nib carefully, dipping it into the ink and beginning work again.

He never read sense into the sentences he inscribed on the parchment. Words? What were they but an arrangement of letters; up-strokes, down-strokes, curves and loops? Something to gaze at raptly, something to view as an excitingly satisfactory whole full of lovely harmonies. And what a welcome change when there was ‘copy’ for an illuminated scroll; what a thrill, an absorbing game, in making the rough sketch and planning out the matter and then preparing the gold leaf and the blue and red pigments. There were colours for you. Red, blue and gold! (pp.165-6).

Most of the Cleft Stick stories have a contemporary setting, and indeed this story makes explicit that Stephen Wain has had this job for forty-eight years since 1882 (a lifetime job indeed) giving it a setting of 1928 – presumably also the year when Greenwood wrote it. But unlike all of Greenwood’s other clerks, fictional or autobiographical, Stephen gains great satisfaction from his work: it is not from his point of view alienated labour (his satisfaction with form over content might be significant in indicating a lack of interest in analysis of the meaning behind the appearance – just as he never questions how he comes to lead the life he does). He likes his solitary work and takes pride in the tools of his trade, which he himself bought, recording the date of their acquisition in an example of his craft using not only copperplate but also the ‘engrossing’ technique of rubricating – that is the decoration of initial capital letters, as originally used in medieval manuscripts of scripture (originally, rubrication meant the use of red ink in initial capitals, but was later expanded to the decorative use of blue and green as well, exactly the colours Stephen uses in his engrossing work – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubrication). He undoubtedly regards his work as certainly a craft and maybe even an art – thus for him mere linguistic or legal sense is unimportant when compared to pure form, the pure form of letters, though even these he sees more as lines, pen-strokes, which communicate fundamentally visual ‘harmonies’ rather than composing legal or honorific texts. Not only that, but Stephen justifiably sees himself as an autonomous craftsman – if engrossing work is commissioned he plans it from the beginning and decides on the execution, using ink, colour, and gold leaf as he sees best.

This makes his employment as an admittedly specialist type of clerk very different from the role of ‘applied writer’ as usually envisaged by Greenwood. Greenwood precisely sees the job of clerk as lacking autonomy and all creativity, an exercise of endless drudgery which is the very contrary of the work of an artist or writer who exercises their own independence and judgement. However, while the narrative does tell the story of his occupation from Stephen’s perspective, it also offers a simultaneous and very different external critical perspective, which views this skilful copyist in the context of the business of Blore & Smith, and indeed in the wider context of capitalism. As a matter of fact, the objective narrator tells us, Blore & Smith had only been established for a year or so when Wain joined, and was not doing that well. It was actually Stephen’s work which put the business on a sound footing and created its reputation. The owner, Richard Blore (his partner Smith was always a fiction), hears from a friend that a facsimile is required of an ‘old illuminated parchment’ called ‘the Detering MS’ which is on display in the Art Gallery. As far as I can see there is no actual ‘Detering MS’ in either Salford or Manchester Art Galleries or anywhere else, so it is presumably Greenwood’s invention (it might perhaps be named somewhat after the ‘Dering MS’, a very early manuscript text of Shakespeare’s Henry IV Parts 1 and 2, though that is not, of course, an illuminated MS – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dering_Manuscript). Blore asks Stephen to copy the Detering MS, and presents his excellent facsimile to the Art Gallery free. This leads to the city’s solicitors, clubs and masonic lodges taking their engrossing work to Blore & Smith and to its success as a Law Stationers. Richard Blore does not single out Stephen for any particular praise, though he does not forget to praise himself: ‘Who would have thought of taking a chance as he had done on the Detering MS?’ (p.164).

Thereafter, the owner and therefore chief beneficiary of the successful business while drawing all the profit he can from his luckily found employee does not otherwise let Stephen Wain occupy very much of his mental space:

After he had discovered Stephen to be so efficient he accustomed himself to his employee’s dependability and, consequently, thought as little of him as he did of his watch. It was there to tell him the time whenever he wanted to know it; otherwise it was out of his mind (p.164).

Wain is just an instrument for Richard Blore: he earns (some of) the money on which his employer can live a pretty undemanding life, but this material fact of their relationship never seems to make it to the surface of Blore’s consciousness. He does go through the motions, visiting Stephen’s work-room every Friday at 5.30 pm to pay his wages in an envelope and making a seasonal variation at Christmas, when Stephen’s wages are each year raised by one shilling. On his engagement in July 1882, Stephen was paid sixteen shillings a week, and every year for forty-five years he had the shilling increase, bringing his wages in 1927 to sixty-one shillings per week or as more usually expressed to three pounds and a shilling per week (the sixteen shillings in 1882 would be the equivalent in November 2024 of around £70, while the three pounds would be the equivalent of around £160, though there is likely to be further complexity to income comparisons across time). (7) As well as this modicum of material recognition of his labour, Richard Blore also makes a similar if occasional gesture of appreciation of Stephen’s skills and artistry: ‘Sometimes, too, he looked over Stephen’s shoulder and pretended interest in his work, signifying approval with a “-er-H’m” (p.166). Clearly, Richard Blore cannot articulate any view at all of the skills on which he parasitically lives. He also performs another empty gesture every Friday for forty-five years when he observes that Stephen’s work-room is damp in one corner, with the wall-paper peeling, and says that he must get this repaired, but sadly never gets round to any action.

However, worse is to come. After forty-five years Richard Blore dies, and this affects Stephen both emotionally and materially. He has taken Richard Blore’s (very moderate) interest in him at more or less face value: ‘It was uncomfortable and disturbing to know that he would never again enter this room of a Friday night, nor observe the wall-paper’ (p.167). Richard’s son Rupert inherits the business but is even more uninterested in Stephen’s part in it, as well as wishing to modernise it: he starts to sell office-furniture and introduces typewriters. Now ‘a girl’ brings Stephen his weekly wage-packet, his annual increment stops, and Rupert refers to his employee of forty-eight years as ‘the old gink’ (p. 167). This is an unusual term and seems only to have been coined in the first few years of the twentieth century; OED defines the word as follows ‘Slang (originally US). Frequently derogatory. A fellow, a guy; esp. an odd, eccentric or foolish man; someone who is unworldly or socially inept’. Twelve examples of usage are given, nearly all from the US, so this looks like the younger Blore has picked up an Americanism in his experience of contemporary life. I doubt that it would be a word the sense of which Stephen would have recognised – making its use for him by Richard Blore even more disrespectful. In as much as Richard might have thought at all about what he intends by the word I think he might mean that Stephen is in his view ‘unworldly and socially inept’ – in short, a failure. Stephen fears for his future in at least two respects: he is now sixty-four years old, and he cannot help notice that less engrossing work is coming in. A salesman bringing in a rare bit of copy for Stephen to work on sympathetically observes that ‘these new firms aren’t going in for this sort of thing nowadays’ (p.168) – instead they want work done quickly on typewriters. Sure enough, soon Stephen is told his services are no longer required – though they will let him know if any engrossing is wanted and then pay him for each job as a one-off.

One thing I have not yet discussed about Stephen’s life is his liking for predictability, with which in fact the narrative opens:

Stephen Wain was a man of habit. He never changed his old-fashioned style of dress, he caught the tram at the same time every morning and followed the same route to work when he alighted at the other end. His shoulders were stooped from a lifetime at a desk: he trotted rather than walked as though he disliked the streets and wished, as soon as possible, to be at his place of business (p.163).

Given this approach to life, the end of of his work routine is devastating for him. He either always was or has become completely adapted to office routine, and I note that as in Greenwood’s interview with the clerk in 1939 the clerk’s job is seen inevitably to lead to an unnatural posture. His only happiness now is when a rare piece of engrossing calls for his talents: ‘It was wonderful to enter the old room and reach his pens out of the drawer.’ On every other day when he wakes in his rented room he has literally and psychologically nowhere to go – he has to go out of the house to be out of his landlady’s way and spends each day on a bench in a public park with other old men with small pensions and nowhere else to spend their time. Inevitably, he catches pneumonia (as of course did Greenwood while unemployed – see Walter Greenwood: Vegetarian Messenger (1934-1935) *) and after two days in the Infirmary dies alone. His box of pens is sent to the landlady by Blore & Smith, and she immediately thinks they are of no value (‘Pens! Puh! Who wants them?’). She gives them to her children to play with but as they squabble over them she throws Stephen’s precious instruments into the fire – pens, nibs, box and his proudly inscribed ownership parchment. This utter disregard of Stephen’s life-work and craft of course only takes to the next degree the obvious disregard for him of Rupert Blore and the only slightly mediated lack of interest of his father, Richard Blore. The lack of value given to literacy and the treatment of the pens as its tools is perhaps revisited or anyway echoed in the novel of Love on the Dole in the treatment of Larry’s books after his premature death:

One of the furniture broker’s men, a tall, gaunt individual with skin-tight clothes, a luxurious moustache and prominent eyes, came to the door of the house carrying a pile of Larry’s books slung about with a length of cord. He pushed past Sally then dropped the books on to the pavement . . . (p.217).

In the film version of Love on the Dole (1941), Sally saves Larry’s books and takes them away with her to Sam Grundy’s house in Wales.

As for each of The Cleft Stick stories there is an illustration by Greenwood’s friend the artist Arthur Wragg, and as usual this makes a striking contribution to the narrative. Here is Wragg’s visualisation of Stephen Wain’s ‘quiet life’, which compresses the whole narrative into a single representative image.

Stephen is pictured in his favourite place, his damp work-room, working in Wragg’s artist’s imagination right under the window where the light is best for his engrossing work. However, Wragg does not otherwise imagine the room as a place of much light, and though Stephen’s head and face and hands and shoulders are front-lit somewhat by natural light, and the upper part of the image is lit more intensely presumably by artificial light from above, the viewer’s main impression is surely of a rectangle dominated by the darkness generated by Wragg’s habitual use of dense black ink, which, from examples I have seen among Wragg’s papers in the V & A archives, he seems to have applied to portions of his original pen and ink drawings in several thick washes with a brush. (8) Of the twelve squares made up by the leaded window panes only one at the top is completely filled with light, while six at the bottom are completely dark except where Stephen’s body and the lettering intervene. One of Stephen’s precious pens is shown in his hand, though his facial expression, which might have perhaps expressed being absorbed in his work, is obscured to a degree by the O of ‘Stationers’ (I am tempted to say expressing as an abstract mouth the howl of misery which Stephen himself never utters nor conceives of). I am not sure that either his hand under his chin or the tilt of the head do suggest absorption or satisfaction, despite the way these feelings are suggested in the story.

And of course the window panes with their leading looks like prison bars with Stephen firmly imprisoned behind them. The narrow column of brickwork to either side of the window replicates this enclosing rectangular effect. The bricks do also look very like the frame of a painting, and in terms of painting genres this is something like a portrait of Stephen Wain, except of course that here the central human subject of the portrait is shrunken into mainly the lower quarter of a picture space which is so explicitly measured into twelve graph-paper-like squares. If it were a conventional portrait, which by definition would value its human subject, then Stephen’s head and body would occupy something like seven of the twelve squares instead of the four squares in which they have some presence here. Instead Stephen is literally diminished by the name of his employer and their business. Of course, Wragg’s adaptation of the portrait genre reflects his sense of how the clerk Stephen is precisely not valued humanly at Blore & Smith’s. Indeed, the whole image is very flat overall, with depth only indicated by the drawing of Stephen’s body: he brings the only signs of life into a flat visual world. Meanwhile much of the image space is dominated or overlaid by the font indicating the name of the owner[s] of the business and the type of business. This illustration seems to me brilliantly to capture many features of Greenwood’s narrative, which shows both the ways in which his quiet and long life at Blore & Smith’s is significant and meaningful for Stephen and at the same time the way that life is produced and dominated by an impersonal and utterly careless business and money-making system. As Greenwood can empathise with Stephen through his own rather different experience of ‘clerking’, so perhaps too can Wragg through his own artistry, which is also predominantly one practised with pen and ink – though for his part he positively preferred working in monochrome whenever he could.

Why did Greenwood (with Wragg) produce this one unusual portrait of a clerk, as seen against his several other representations of the clerkly life? I simply do not know – perhaps he knew such a clerk in a Law Stationer’s in Salford who provided some contrasts to his own experiences of being a clerk? The story does share some themes with his other representations of clerks in its exploration of exploitation, but is distinguished by its simultaneous study of Stephen’s own satisfaction in his rather specialised writing and engrossing skills. Perhaps Greenwood felt, especially in his early days as a writer who sent out short stories and novel only for the them to be rejected, a kinship with Stephen as a creative artist whose work went largely unrecognised? After all, in the period between 1928 and 1931 Greenwood wrote twelve short stories of which only one was accepted for publication. His first novel/s forming The Prosperous Years trilogy were also sent back by publishers.

Greenwood was, of course, not the only early twentieth-century writer to write about clerks, and indeed there is a book-length study of literature centring on clerks by the book-historian and critic Jonathan Wild, titled The Rise of the Office Clerk in Literary Culture 1880-1939 (Macmillan 2006).

Wild initially thinks that both actual writing about the growing occupation of clerk and later critical attention is surprisingly thin given the huge growth of this occupation during the modernisation of office work in the period he studies:

The anonymous reader of the manuscript of this book describes the office clerk as ‘a haunting and heretofore ghostly figure in fiction’. My own research into this topic began from a similar perception of the spectral nature of this figure. Why, I wondered, had such a representative member of the urban scene apparently left behind so few traces in British literature between Charles Dickens and the inter-war period? (p.1).

However, in the course of his explorations, Wild rediscovers a substantial late nineteenth and early twentieth-century literature about the clerk, beginning with Edwardian representations by authors themselves emerging from that social milieu, including H.G. Wells and Arnold Bennett, and going on to include post World War One writers such as J.B. Priestley, especially in his best-selling novel of office life, Angel Pavement, of 1930. Wild identifies a clerkly literature specifically arising during each of the periods of the First Word War and the Depression. Indeed, he shows that the position of clerks was in fact made increasingly precarious in the period of the slump, though he notes some difficulties in interpreting the statistics because many clerks were not eligible for unemployment benefit (because they had earned too much while employed to later qualify for benefits under the rules of the period) or were extremely unwilling to claim it because of their sense of their own status. Nevertheless,

One contemporary report suggests that security of employment was, by 1935, ‘for the great majority of clerks … a thing of the past, and they have therefore acquired the last decisive characteristic of the wage worker, that of uncertainty with regard to the future’ (F.D. Klingender, The Condition of Clerical Labour in Britain, Martin Lawrence, 1935, p. 98). Although white-collar unemployment during the 1930s is little recognised today, this phenomenon was much debated in the fiction and non-fiction of the period. In these texts, the putative complacency of secure and comfortable suburban life was challenged by a wide variety of writers seeking to investigate the Depression’s hidden victims (here Wild indeed cites the novel of Love on the Dole, p.169, referring to a passage when Sally regrets Harry refusing to pursue the life of a clerk, leading to his long-term unemployment), (p.147).

Writing about clerks in this interwar period, with both documentary and fictional contributions, was therefore often focused on the clerk’s experience of the Depression and unemployment:

Perhaps the most important and revealing development evident in this field was the emergence of a number of young and often previously unpublished novelists whose early works depicted the experience of modern lower middle-class life. A selection of texts capable of sketching out the wider picture might include the following: Malcolm Muggeridge’s Autumnal Face (1931), a sympathetic account of the effects of unemployment on a middle aged clerk; V.S. Pritchett’s Nothing Like Leather (1936), an autobiographical novel of a young clerk’s experiences in the leather industry; and Hugh Preston’s Head Office (1936), which describes a single day in the life of a large London firm. Among the more experimental texts to emerge on this topic were Arthur Wellings’ Each Stands Alone (1930), a Joycean study of frustrated love in a bank; E.A. Hibbitt’s The Brittlesnaps (1937), a left-leaning and technically bold account of the effects of unemployment on a white-collar worker’s family; and Frank Tilsley’s novels The Plebeian’s Progress (1933) and I’d Do it Again (1936) which offer varyingly radical socialist readings of the suburban clerk’s economic position during the Slump.

E.A. Hibbitt was a Salford writer and indeed Greenwood helped him with drafts of his first two (and possibly his only two) novels (see A Second Walter Greenwood? Edward A. Hibbitt, Salford novelist * ). Greenwood certainly also knew Frank Tilsley since he attended the humanist christening of his daughter in July 1938 (see that year in Walter Greenwood’s Biographical Timeline *) and they had both published their first novels about unemployment in 1933, with considerable impact in each case.

Wild explores in some detail Priestley’s Angel Pavement and Tilsley’s The Plebeian’s Progress as being examples of two characteristic ways of responding to the life of clerks. He argues that Priestley, while seeing fully the strain which the Depression puts on those who work as clerks, represents them more optimistically as resilient, displaying the domestic courage of the ‘little man’. Angel Pavement deals with the offices of a whole company, but Wild focuses on the senior clerk and cashier Herbert Norman Smeeth, who we might compare in some ways to Stephen Wain. Wild quotes the novel’s account of the satisfaction which Smeeth takes in his work:

He had spent years making neat little columns of figures, entering up the ledgers and then balancing them, but this was not drudgery to him. He was a man of figures. He could handle them with astonishing dexterity and certainty. In their small but perfected world, he moved with complete confidence and enjoyed himself. If you only took time and trouble enough, the figures would always work out and balance up, unlike life … . (Priestley, p.37; cited by Wild, p.155)

Wild then comments:

Priestley’s method here, effectively likening Smeeth to a monk absorbed in an illuminated manuscript, is calculated to provoke a sympathetic re-evaluation of clerkly contentment and efficiency (p.156).

The comparison of Smeeth’s satisfaction to that of a monastic scribe perhaps coincidentally maps well onto Stephen’s satisfaction with his engrossing work, but also suggests that there were other such literary recognitions of clerking as rewarding.

However, Wild’s account of Tilsley’s more desperate depiction of the clerk also suggests that Greenwood’s generally negative portrayal of clerks, and his underpinning critique of the social context in which Stephen Wain works , was also not unique to him. In Tilsley’s The Plebeian’s Progress (1933), Allen Barclay, though born into a poor working-class family in Manchester does well as a clerk. He marries Jane and at the peak of their success he earns £5 a week as a trusted senior clerk in a local family-owned mill and they are able to rent a good house and buy furniture. However, as recession bites the mill goes under and Allen loses his job. He does in due course get another job as a clerk, but steals money from his employer to pay missed rent and keep up the life which they have worked hard to achieve. He is discovered and sacked and cannot get further work as a clerk. Everything unravels: they lose the house and the couple’s relations become very strained. They move into a miserable single room and slowly begin to starve. Allen in the end kills Jane to end her suffering and wants only to end his own life by being hanged for murder, which he duly is. Greenwood’s work was often seen by contemporary reviewers as grim, or even excessively grim, but Tilsley’s work surely trumped Greenwood for bleakness (for a little further discussion of the novel and some contemporary reviews, several of which see Tilsley as moving beyond realism or the real – and into melodrama, see my https://reading19001950.wordpress.com/2022/02/20/the-plebeians-progress-1933-by-frank-tilsley/).

Greenwood’s writing about clerks is mainly autobiographical in one way or another, or documentary in one case, with the exception of ‘A Quiet Life’, which is a story that does not like Priestley and Tilsley’s novels focus on the clerk and unemployment. Stephen loses his job not because of the Depression but through changes in business demand and culture between the late nineteenth century and the first three decades of the twentieth century. He has (just) enough to scrape by on after his working-life ends (the story specifies that he has saved £30 across his working-life of forty-eight years and that he is entitled to draw ten shillings a week in old-age pension). Nevertheless, his solitary habits, his satisfaction with his craft of penmanship, and his clerk’s wages do mean that he has no alternative life to go to once his work is finished: no home of his own, not even a rented one, no wife or family, no friends, and presumably no hobbies or outside interests. His single-minded devotion to deed-writing and engrossing for Blore & Smith is the end of him.

Greenwood’s writing about clerks has, with the exception of his story about Stephen Wain, a very precise focus and motivation: it is about avoiding being a clerk. That is what motivates Harry Hardcastle to get a ‘proper’ job as an engineering apprentice at Marlowe’s works, it is what motivates Walter to leave the Co-op offices for work with horses and it is at least one of his motivations for becoming a writer (though he had compelling social and political motives too) – a very different use of his pen and ‘fair hand’ which amazingly enough did take him to the different kind of life which for years seemed only a dream. Little notice has I think been previously taken of Greenwood’s life-long engagement with the lives and livelihoods of clerks.

NOTES

Note 1. Letter in the BBC Written Archives, Caversham Park, Reading, together with subsequent correspondence and an internal BBC report on Something in my Heart.

Note 2. The RASC was disbanded in 1965 and its functions reallocated to other newly-founded corps. There is an introduction to the history of the RASC in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Army_Service_Corps). However, the most helpful outline of the role of clerks in the Corps is on the Forces War Records website, which specifies the RASC provision of ‘staff clerks to headquarters units’: https://uk.forceswarrecords.com/unit/134121/royal-army-service-corps. George Forty’s generally invaluable and comprehensive Companion to the British Army 1939-1945 (the History Press, 1998, this Kindle edition 2009) oddly does not specify this role in its section on the RASC, specifying only ‘the role of ‘MT [motor transport] clerk’ in the Corps (p. 136).

Note 3. See my earlier (not very conclusive) discussion of his illness in Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole – Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, 2018, pp. 243-4.

Note 4. Letter of January 15 1944, sent from Hiders Farm, Pump Lane, Framfield, Sussex; from Arthur Wragg’s Correspondence in his uncatalogued papers, file AAD/2004/8 in the V&A Archives.

Note 5. Again from the same letter in V&A Archives, file AAD/2004/8.

Note 6. I am not an expert on handwriting and my information is based, in addition to the definitions given by OED, on Wikipedia entries for ‘Copperplate’ ‘George Bickham’ and ‘Roundhand’. Of these the ‘Copperplate’ entry seems the least strong. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copperplate_script , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Round_hand and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Bickham_the_Elder.

Note 7. Figures derived from the Bank of England Inflation Calculator: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator.

Note 8. For example, in some surviving full-scale drawings for his 1935 book The Song of Songs (Selwyn & Blount) in Wragg’s uncatalogued papers in the V & A Archives (Box AAD/2002/11 ‘Sketches and Drawings’, sub-folder for The Ten Commandments (unpublished) and Song of Songs (published1935) projects). Though there are two surviving sketches for illustrations in The Cleft Stick (for ‘Mrs Scodger’s Husband’ and ‘The Practised Hand’, also in box AAD/2002/11) the final versions of the fifteen illustrations for the collaboration with Greenwood are not among his papers. Letters to Wragg suggest he sometimes sold the original pen and ink drawings once a book was printed. Thus there is a letter to Wragg from a John Arlott of Southampton, dated 28 May 1942, asking if he can buy the ‘original drawing’ of ‘Mrs Cranford’ and a letter from a Mrs M. Cole dated 20 November 1933 agreeing to buy a small drawing from The Psalms for Modern Life (1933, Selwyn & Blount) – she writes that she can only afford a smaller illustration. Both letters are in box AAD/2002/1, ‘Fan-mail’. Papers studied during archival research carried out by the Author on a visit to the V&A Archives, then at Blythe House, London, on 20 June 2019.