I admit that this may look at first glance like a rather niche piece of research, but the bookie Sam Grundy’s car ownership is clearly unique in Hanky Park and I think there is something worthwhile and significant to say about it, especially bearing on the car’s role in Sam Grundy’s campaign to make Sally become his mistress, despite her obvious unwillingness and repeated refusals. His car in both novel and film is always a notable spectacle in the streets of Hanky Park, and bears a very public witness to his own almost unique role as the rich man who made his money in Hanky Park (of course by exploiting the poverty, hopes and dreams of its people), and who alone can leave the place when he takes a fancy to (everyone in the city knows of his fabled holiday house in Wales). (1) The car is thus a sign of his obvious mobility as well as of his wealth. To be able to leave and return to Hanky Park at will makes Sam Grundy extraordinary: as Sally observes to Larry early in the play (though not in the novel nor film): ‘There’s not many gets out o’ Hanky Park – except through cemet’ry gates’ (Cape edition, 1935, Act I, p.16). This is in the context of her noting that she has never had a holiday in her life.

Not surprisingly Sam Grundy’s car does not feature at all in the play – too much trouble to stage physically and therefore easiest and most economical not to refer to it at all. His car does though play quite a significant role in the novel and that role is fully translated into the film too. At many points in the novel when Grundy is trying to persuade Sally to become his mistress he does so from inside his car. These moments when he blatantly tries to seduce her with promises of money or material rewards and indeed holidays are, as it were, both pedestrianised and domesticated in the play, where just as shockingly in a different mode Grundy comes into Mrs Hardcastle’s own kitchen to ask her permission to make Sally his mistress, without involving Sally in the bargaining. Mrs Hardcastle asks Grundy to leave her house before either Sally or her husband come home, saying straight that if Mr Hardcastle finds Grundy in the house he will kill him (Cape edition, Act III, p. 88). In the novel Grundy’s position inside the car and seated emphasises the difference in power between him and his female target who can only walk or stand in the streets on her way to and from work, and is thus vulnerable to Sam’s predatory mobility. Sally, of course, is one inhabitant of Hanky Park who is not at all impressed by Sam Grundy’s car and who openly rejects the impact it is intended to have.

Sam, as part of his business identity, consistently represents himself as a spectacle of wealthy success and apparent good-fellowship through his speech, behaviours and his traditional bookie’s costume. The latter is described in the novel when Grundy comes out of his house to put on some good-for-business impromptu street-theatre to pay out on Harry’s wondrous thrippenny treble win:

Preposterous-sized diamonds ornamented his thick fingers and a cable-like gold guard, further enhanced by a collection of gold pendants, spade guineas and Masonic emblems, hung heavily across his prominent stomach. He chewed a match stalk; his billycock rested on the back of his head; he wore spats. Self-confidence and gross prosperity oozed from him. The notorious Sam Grundy himself (p.113).

The still below shows how the film translated this image into its costuming:

The car is no doubt useful for both business and ‘pleasure’, but is also a further means for Grundy to broadcast his spectacular life-style across his whole territory.

In the novel there are twenty-one references to cars (as located by searching the kindle edition), of which eighteen refer directly to Sam Grundy’s car. However, the other three car references are worth looking at as well because they too suggest power differentials between those inside and beyond Hanky Park, and thus provide a context for the particular instance of Sam Grundy and his car. In the lunch-break explanation to his workmates of what money, commodities and labour really are Larry includes cars as one of his examples of manufactured products (though one might note also the trains and ships as embodying both manufactured products and mobility):

‘Well, let’s call the things you want “commodities” ‘, he turned to the wall to make an addition to the pound sign: ‘≡ commodities’. ‘Remember,’ he said, ‘that the word means anything, everything, that people need. Food, clothing, houses, motor-cars, trips in ships and on railways. Do you understand that?’

Another grunt.

‘Very good,’ Larry continued: ‘Now, you know that there’s only one class of people who provide all these commodities, don’t you? And those people are us. We, you and I and the rest of the working folk. We are the ones who plough the soil and grow food; we make the clothes and the houses and the motor-cars and the ships and trains; and we man the ships and drive the trains. In short, it’s our labour power that makes all and every one of the commodities. You never see a rich man doing any of these things, do you?’ (p.183).

This analysis makes clear (perhaps as much for the potentially upper or middle-class reader as for the actually present working-class workmates?) that while the workers at Marlowe’s engineering works make such goods and provide such services as driving them they do not actually have much if any access to their benefits themselves. The third reference in the novel to cars other than Sam Grundy’s makes clear that while cars in Salford are a rarity they are becoming more common in more prosperous parts of Britain, including in its neighbouring city of Manchester, where mobility is more possible for more people. The protest march against the Means Test is merely a nuisance or a spectacle to ‘outsiders’ trying to pass through Hanky Park to Manchester:

Traffic accumulated behind the surging crowd: lines of tramcars, motor-cars and lorries going to and coming from Manchester. Clanging of tram bells; hooting of motor horns; faces pressed against the glazing of the upper decks of the trams; Press men leaning out with cameras in their hands (p.204)

Like Sally saying she has never had a holiday so too Harry on seeing a passenger train passing on the track beneath Downey Hill notes with frustration the ‘incredible’ fact that he has never been on a train in his life (p.82 – in the film the comment is given to Helen and Harry replies that neither has he). Later, the out of work Harry catches himself day-dreaming of setting off on a train with Helen for their honey-moon before pronouncing himself ‘barmy’, for under current circumstances that will never happen (p.171). Of course, it is not only cars, and travel by train and ship which most people in Hanky Park have little access to – they also have insufficient access to food, clothing and housing. Meanwhile Sam Grundy as well as having more than sufficient access to all these commodities in addition actually owns his own car giving him a ready mobility to pursue his own interests at all times.

The novel’s first reference to a car is in fact to Sam Grundy’s car and to the ‘advantages’ it gives him as seen through the foul view-point of Ned Narkey – though that view only lays bare Grundy’s own thinking and indeed practice:

‘You’ve got women all o’er place.… Ah know.… Kate Gayley was mine when Ah’d a pocket full o’ dough.… Shuts bloody door i’ me face sin’ you tuk her out in y’ car. Told me she’d cut me out cos she was feared o’ neighbours talkin’ an’ gettin’ her widder’s pension stopped.… Ah ain’t daft, though (p.116)

For Narkey relations with women are only for him matters of exchange of sex for money or other ‘rewards’, which is true too of Sam Grundy, but his car gives him an aura of superior status and both a mobile location for his sexual predation and a geographical range (as Narkey notes in his opening comment, ‘You’ve got women all o’er place’) ). It is one reason why he can pop up all over Hanky Park and harass Sally at will without her being able easily to avoid him:

Night was falling. She [Sally] was on Broad Street now passing the parish church. Her train of thought was interrupted by the sound of a hoarse voice speaking her name. She turned her head. Sam Grundy’s fat, apoplectic visage smirked at her from the illuminated rear windows of his car. It kept pace with her walking; doubtless the chauffeur was obeying Sam’s instructions. He put his face out of the window: ‘Hey, Sal,’ he cried, winking: ‘Wharra bout a little ride, eh?’ he nodded and winked again: ‘Ah’ll get y’ back, early.… Go on.… What’j’say, eh?’ Another grin and a wink. She scowled at him, voiced a contemptuous exclamation, walked behind the car and crossed the road without even another glance. Surlily she turned into Hanky Park. The fool to think that his most tempting offers could ever be of interest to her. She put him from her mind (pp.142-3).

Her response to him as utterly unattractive and unwelcome is clear, but apparently unimportant to Grundy. This is the only time when Grundy is driven by his chauffeur, presumably to allow him to pester Sally more easily, and another example of how his money gives him power over those more vulnerable than himself – though on all other occasions he drives himself, perhaps requiring a kind of privacy. However, Sally is not a passive victim – she resists as much as she can, both verbally and by walking across the road behind his car physically to disengage from him. She is absolutely clear that his offers of material ‘reward’ are no temptation to her at all.

However, later on, after Larry’s death, Sally desperately needs money to pay for his cremation, and since Grundy is the only one in Hanky Park likely to be able to lend her the large sum of five pounds, she has to turn to him despite the very large risk to herself. She locates him readily through his car, that movable symbol of his wealth and power:

She found herself paused by the open doors of the Duke of Gloucester. Sam Grundy’s motor-car stood pulled up by the kerb; she heard his raucous laugh within the public-house. ‘Five pounds,’ the words repeated themselves monotonously. After all, why shouldn’t she ask the favour of him? Why? What a question. What alternative was there? Who in Hanky Park possessed such a sum of money: and who, possessing it, would lend it to her knowing her circumstances (p.218).

Sam leaves the pub saying that his drinking companions are no ‘pals’ of his and suggesting that Sally comes for a drive in his car where they can discuss the loan in private, but she knows that to accept this offer would be to make herself vulnerable both to Sam himself and potentially to gossip: ‘Ah want no drives in no cars’ (p.220).

However, in due course the ever-worsening crisis of her family – rather than her own situation or wishes – induces her to do what she has so determinedly resisted: to enter Grundy’s car for the first time. She is in fact as ever resisting Grundy’s proposition to go for a drive when her brother Harry gives Sam Grundy an opportunity to overcome Sally’s extreme reluctance by explaining hurriedly that Helen is giving birth and has ‘been tuk bad’:

Already he [Grundy] was out of the car and holding open the door: ‘Come on, Sal,’ he urged. She shrugged and stepped inside, Harry following, babbling the inconsequent news of his successful application for Poor Relief, and he had scarcely finished when the car pulled up outside Mrs Dorbell’s home. Those few neighbours remaining, pursed their lips, exchanged significant glances, winked and nodded knowingly as Sally stepped out, followed by Harry. They smiled, forcedly, as Sam explained his presence and the car as a result of a fortuitous meeting (p.240).

Grundy takes advantage of this excuse and gives the superficial appearance of being helpful. It it notable in the passage above that Sally has anyway already been judged ‘guilty’ by the neighbours despite in no way having given in to Grundy’s demands. Mrs Nattle specifically associates Sam Grundy’s car with Sally’s ‘surrender: ‘ “All same, Sam Grundy’n her are gettin’ pretty thick. Ah see his moteycar everlastin’ hangin’ about street corner nowadays,’ warmly: ‘He’ll be gettin’ his way wi’ her …” ’ (p.227).

This reference on page 240 to Sam Grundy’s car is the last in the novel, and when Sally has finally made her bargain with Grundy for the sake of her family, there is a car involved but not Sam’s, perhaps implying that he has put enough ‘personal’ effort into the matter now the ‘bargain’ is made – instead he provides the means for a taxi to take her away from her home to join him at his holiday home in Wales, presumably via a train journey. The taxi in North Street is an unprecedented event, and as in the previous passage the scene shows how public rather than private is Sally’s ‘choice’:

A knot of neighbours standing outside the home of Mrs Nattle, regarded, pensively, the front door of Mrs Hardcastle’s home from which a taxi had just driven away. ‘High-ho,’ sighed Mrs Jike: ‘I wouldn’t turn me nowse up at a fortnight’s holidiy where she’s gorn. Strike me pink, I wouldn’t!’ (p.252).

Mrs Jike (and indeed Mrs Dorbell) think only the ‘rewards’ of Sally’s contract are worth noticing, and have no imagination of any quantity of inherent pain, suffering or sacrifice for her.

The 1941 film makes very good use of Sam Grundy’s car in related ways, realising its meanings in visual and cinematic ways supplementary to those available in a novel’s repertoire. One contrast is that while in the novel Sam Grundy has simply ‘a car’ (that being exceptional enough in itself) with no hint at size, brand or model, the film more or less has to use a real car, and its choices about what kind of presence the car has feed into the film’s dramatic meanings. The still below is from the scene in which Sam Grundy’s car makes its first appearance in the movie – the car pulls up just as Sally comes down the stairs on the left side of the street:

Clearly, the car stands out against the drab brown dark scenery of Hanky Park’s streets, as wonderfully represented in the ‘big sets’ John Baxter and his crew built on the lot of the Rock Studios, Elstree. These sets were singled out as exceptional by Kinematograph Weekly:

BAXTER WORKING ON BIG SETS NOW.

Many big settings have been designed for the latest British National film Love on The Dole . . . Art Director Holmes Paul, renowned for his realism, has spared no effort to give added authenticity . . . [and] so carefully studied has been the detail that water actually ran down the gullies, imitating a ‘life-likeness’ that has to be seen to be believed . . . Many other large sets are planned for the picture and the railway-yard scenes, in which the local ‘pub’ features so prominently, have already been filmed (Kinematograph Weekly, 5 December 1940, p.23).

The car is displayed against this realistic set as polished and gleaming and evidently a sign of wealth – the eyes of the passing pedestrians are drawn to it – though what appears to be its dark paint finish also gives it a certain gloomy unity with the bleak colours and lighting of Hanky Park.

Here is a clip (0.29 seconds) showing what happens next: https://youtube.com/clip/Ugkxd2iOIpgGLyuW_V9K6Sr6L2Ts54pWUDpo?si=XAHahu-Fot9QYs99 (as with all YouTube clips it runs on a loop so just click back to this page when you have watched it enough). Sally is clearly not afraid of Sam Grundy – he invites her to go for a ride with him with an air of (totally unconvincing) innocence – and she turns his words against him wittily by making metaphorical his literal meaning, replying that he has taken ‘too many for a ride already’. He begins to open the car door, but she kicks it shut (showing a deliberate lack of respect for his spectacular property), and she dismisses him by telling him to ‘take yourself for a ride’. He accepts the rejection (for the moment) and drives off. Though the dialogue is somewhat differently developed this scene has a similar function to the first car scene in the novel: it shows how Grundy can use his car to pester Sally anywhere in Hanky Park (the opening and conclusion of the clip show how the appearance of Grundy’s car instantly takes Sally from a safe environment with first Jim and which is then restored when Larry appears in the street after Sally has told Grundy to get lost). However, the physical set up is rather different from in the novel and this for the present shows the power relations apparently reversed. Where in the novel Grundy’s chauffeur drives at walking pace so that Sally cannot escape Grundy’s unwelcome attention, here the standing Sally is shown as higher than the seated driver, and more dominant, addressing Grundy as an equal, or rather an inferior, and physically preventing his exit from the car. As Grundy’s too ready acceptance of her dismissal may suggest, this is only round one.

The car itself was no doubt also ‘read’ by viewers, though presumably with varying knowledge of motor-vehicles, so it is worth trying to establish what make and model it is and seeing what it might have signified, for example about social status, in 1941 and/or 1931 (remembering that the film is retrospective and set in 1931). The shape of the car is clear enough from this first appearance, but later shots are helpful in showing (if in a blurred focus) the bonnet, windscreen, radiator cap and bonnet badge. The blurred focus may suggest that John Baxter was not especially keen on giving a free advertisement for a car brand, but if I can read the car nevertheless, then surely so could (some) contemporary viewers. Here are two edited versions of a still, increasingly close-up to that radiator badge, as well as winged radiator cap symbol:

I am not an expert on vintage cars (or more technically ‘post-vintage cars’, which as we shall see is the definition applying to this car under British car collectors’ terms), but I think this radiator badge (as well as the modestly winged radiator cap) is that of the Wolseley company, though it differs from many examples in not having a winged surround. Nevertheless, it looks like the central oval bearing the Wolseley name, and I have found photographs of Wolseley cars which do have a simpler badge like this. its detail is shown in focus in this modern reproduction pin badge, which is faithful to the font and shape of that core oval marque:

Moreover, the overall shape of the vehicle is certainly that of a Wolseley. I think it is a model derived from the Wolseley Hornet Light model, but is probably one of the later ‘heavier’ developments which were broader and generally more substantial. The closest image I have found is not identical to Sam Grundy’s car (the spare wheel is on a different side, the headlights are slightly differently mounted, and the bonnet badges have some differences in position) but it seems very similar in most respects, including the characteristic windscreen shape. This image below is of a Wolseley 21-60 County model saloon from 1935 which I have placed next to an edited still of Sam Grundy’s car for comparison (County model image reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 2 Generic Licence – see https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wolseley_21-60_County_1934_(14860759079).jpg).

There is another piece of evidence in the film about Sam Grundy’s car which helps us to date the car fairly precisely. Though the registration plate is not visible in this front view of the car, the rear plate is in later views of the car in the film, showing, I am fairly certain, that the registration is ‘KV 319’.

A useful web-site gives a table of the dates and places of registration for cars before 1940, and this tells us that Sam Grundy’s car was (in fact rather then fiction) registered in Coventry between November 1931 and July 1934 (see https://www.oldclassiccar.co.uk/registrations/kv.htm). It is the post-1930 date which from a current perspective makes it a ‘post-vintage’ rather than a vintage vehicle (see https://vintageandclassicspares.co.uk/what-is-the-definition-of-a-vintage-historic-or-classic-car/).

Altogether this information about Sam Grundy’s car suggests that, as with all the production detail in John Baxter’s film, it had been carefully chosen to be exactly appropriate to the film-narrative. If in 1941 the car was at least seven years old and possibly ten year’s old, and perhaps looking a little nostalgic and period-piece, though still solid, in the 1931 setting of the film it represented a brand new, prestigious, powerful and expensive vehicle. The Illustrated London News in 1932 carried a Wolseley advert for two different models of 21-60 County Saloons with the cheaper of the two priced new at £395. Remember how thrilled Harry and Helen are when his bet wins the unimaginable sum of £22 – as Harry’s father says, he will never see that much money again in the rest of his life. Or consider Larry Meath, a qualified engineer at Marlowe’s works, who is paid 45 shillings a week, the novel tells us: I calculate it would take him more than three and a third years to save that amount assuming the impossible condition that he had no other expenditures whatsoever. According to the Bank of England Inflation calculator a product costing £395 in 1932 would be the equivalent of one costing £22,829 today. Sam Grundy can afford this kind of figure unlike almost everyone else in Hanky Park, and is happy to display that wealth every day as a spectacle in the shape of his car. I think too the description of the Wolseley 21-60 County Saloon in the advert might have appealed to his sense of spectacle (and no doubt his complacent sense of his own worth):

The six-cylinder power unit, a masterpiece of engineering, gives amazing speed and wonderful acceleration . . . the graceful lines of its ultra-modern coachwork, equipped with every appurtenance for comfort and convenience are matched by the perfect taste of its interior and exterior finish (15 October, 1932, p. 45)

Of course, film audience members would have differential (as it were) knowledge about cars, but the impact of Sam Grundy’s Wolseley Saloon would surely count, from his viewpoint, to his advantage, but, from the film-viewer’s perspective, in many ways against him.

The next appearance of Grundy’s car in the film shows a second instance of his persistent pestering of Sally, as he parks outside the mill where she works to waylay her at home-time:

Here is a clip (60 seconds) of the subsequent interchange between Sally and Grundy: https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxypFH-JHei3zxcNDeFiBEdVRdkQHxxuPT?si=M9Jmn8PYB9bxICKv (at 1:25:27). As with their first exchange centred on Grundy’s car Sally challenges her harasser, rejecting his (again patently deceitful) offer that he just wants to take her to the pictures, and his grossly superficial suggestion that this could console her for Larry’s death. She rejects verbally his implication that she owes him for the loan of the five pounds for Larry’s cremation and he in turn rejects verbally the notion that she has to pay him back, but clearly beneath the surface she now has a greater sense of danger and he a greater sense that he has some leverage over her. I think this is shown visually by her equality in height with the seated driver in this scene, and her increased nervousness when talking to Grundy as compared to the first scene with his car. Nevertheless, she keeps up a determined resistance, first rejecting the ‘relationship’ which Grundy is trying to force on her in public through his presence and that of his car, and which at least one of her two workmates seem inclined to accept as being the case. She then consistently and openly contests in speech and gesture the veracity of Grundy’s words: ‘a job’, ‘housekeeper’, ‘a grand time’, ‘fair and square and above board’. It is at this point when, very much as in the novel, Sally resistance is undermined not by her own weakness or Grundy’s exercise of power but by the responsibility she feels to her family’s desperate circumstances. This is very much in line with the novel’s representation of the scene, though the dialogue is different. Here is a still of Sally at last and very reluctantly just about to get into Grundy’s car, persuaded unwittingly by her brother Harry and absolutely knowingly by Sam Grundy himself:

Here is a clip (60 seconds) showing the car journey and arrival at Mrs Dorbell’s house where Helen is having her baby (not as we shall see in the clip due to much sympathy or charity from Mrs Dorbell): https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxCFzklBNU0PZADSmnml803pqPWstzG2ka?si=wzeuCbNM5rEsYxET . At the start of the clip Sally is resisting Grundy, but Harry’s arrival precipitates her getting into his car, if very reluctantly. On arrival at Mrs Dorbell’s house, Sally gets out of the car and formally and distantly thanks Grundy, while he says that he will be waiting for her, though she requested no such action. Though Grundy indeed seems to fade into the background as Harry becomes the seeming main focus of the scene, in fact this scene is a crucial turning point when Sally, overhearing Mrs Dorbell’s narrowly rational but utterly heartless and self-centred admonition to Harry, realises that Grundy is the only way out for Harry, Helen and her parents, even though at a terrible cost to herself. She leaves Mrs Dorbell’s house where she has been upstairs with Helen and gets into Grundy’s car where he instantly concludes that he has at last triumphed over her. The shot of him turning wordlessly to face her in the back seat, with his face lit from below, brilliantly but horribly shows his moment of positively devilish self-satisfaction at his conquest of her independence:

He then drives her away from her home. That is the final appearance of Sam Grundy’s car in the film, which in itself introduces a difference from the novel. There Sally is taken away from her parents’ house in a taxi paid for by Grundy. Indeed, there is a photograph from the set of Love on the Dole which suggests that Baxter and his team did at one point plan to include that exit in the film. This photo is a rare image of John Baxter; he is talking to Sally (Deborah Kerr) who is dressed in her film ‘going away’ clothes, including a fur stole, which clearly Sam Grundy has funded, and both stand next to what I identify as an Austin 12-4 taxi from its bonnet badge and characteristic shape:

As with Grundy’s Wolseley saloon, this vehicle seems to have been carefully chosen to have the right appearance for a 1931 setting – its GW registration shows that it was registered between December 1931 and March 1932 (though in the London area – see https://www.oldclassiccar.co.uk/registrations/gw.htm). However, it was surely the right decision not to use it at the end of the film, but to concentrate the drama already set up and use instead the car which in Sam Grundy’s hands has been the vehicle of Sally’s forced if also negotiated downfall and the site of her sustained resistance to Sam Grundy’s abuse of his power and wealth. Both in the novel and the film everything counts and that includes Sam Grundy’s car – though what really matters in the car scenes is Sally’s resistance and the economic circumstances of her family which, in miniature, exemplify the economic position of some millions of people in the Depression, and which eventually force her to make the choice which is no choice and get into the predator’s car, once unwillingly and then the second time by a kind of dreadful exercise of agency.

Greenwood clearly did have, at least later, some thoughts about what Sally’s life would actually be like in Grundy’s house in Wales and developed these ideas in fiction when asked to write a short story sequel to Love on the Dole. I give an account of this story in What Sally Did Next: Greenwood’s Sequel to Love on the Dole (‘Prodigal’s Return’, John Bull, January 1938). Readers may be somewhat comforted in advance by knowing that Sally, despite having ‘given in’ to Grundy, keeps up her campaign of resistance, and in material ways thwarts his desires and makes sure that that house in Wales is no longer a place which further reinforces his sense of his own power and success, but rather a site of continued opposition to his ego and an unhappy place for him too.

NOTES

Note 1. Grundy is almost unique for there are two other rich men in Hanky Park the novel associates him with – however he is the only one who presents himself as a public spectacle and a self-made success and who is therefore envied and even in a sense admired by the inhabitants of the place. Grumpole and Price are much more evidently life-denying figures linked to restraint, miserliness and a kind of self-denial, while there is a carnivalesque aspect to Grundy – if one does not look too deep. See the narrator’s commentary on these three figures early in the novel which sees them as jointly helping to keep the rotten subsistence economy of Hanky Park going to their own advantage and as a kind of double-edged crisis ‘support’ system:

Sam Grundy, the gross street-corner bookmaker, Alderman Ezekiah Grumpole, the money-lender proprietor of the Good Samaritan Clothing Club. Price, the pawnbroker, each an institution that had grown up out of a people’s discontent. Sam Grundy promised sudden wealth as a prize, deeper poverty as a penalty; the other two, Grumpole and Price, represented temporary relief at the expense of further entanglement. A trinity, the outward visible visible sign of an inward spiritual discontent; safety valves through which the excess of impending change could escape, vitiate and dissipate itself (p. 24).

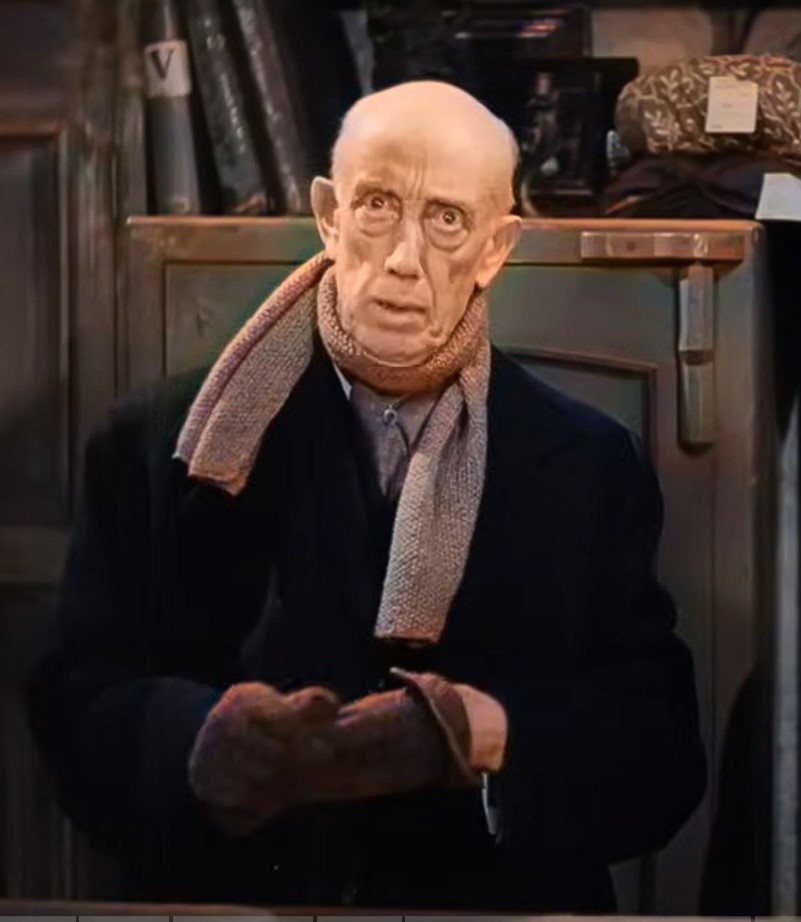

Grumpole makes no real appearance in either novel or film, but Price has a cameo near the opening of both versions, showing that though he may be equally rich, he is not likely to be a figure of envious admiration like Sam Grundy. He makes his money from the necessity of those in Hanky Park to count every penny, but his profits make him no less penny-pinching himself. As his wonderful portrayal in the film by the uncredited A. Bromley Davenport (1867-1946 – see his IMDB entry) in the film suggests, Price is precise, miserly and cadaverous where Grundy at least gives the illusion of being ‘generous’ and devil-may-care. Do compare their two film images!