In 2021 I published an article on this site about a portrait of Wendy Hiller in her role as Sally Hardcastle in the play of Love on the Dole, now part of the National Portrait Gallery collection: The National Portrait Gallery Portrait of Wendy Hiller as Sally Hardcastle (1935) by Thomas Cantrell Dugdale * . This article is about a second example of that rather specialised portrait genre, actors who played a role in Love on the Dole on stage. The portrait in question is first referred to simply as an exhibit in the Leamington Spa Courier‘s report of the touring Royal Society of Portrait Painters exhibition at the Leamington Spa Art Gallery. Under the sub-headline ‘Dramatic and Subtle Contrasts’, the report notes that ‘Beautiful and striking women provide subjects for many of the portraits’, but does not say to which category belongs ‘Drusilla Wills in Love on the Dole by J. A. Grant’ (8 April 1938, p. 4). As we shall see, it was most likely to have been under ‘striking’, in a broad sense.

The Society of Portrait Painters had been founded in 1891 by a group of portrait painters who felt from their own experience that the annual Royal Academy Exhibition tended to exclude portrait paintings, not seeing them as a high-ranking genre – though prestige was no doubt enhanced by the title ‘Royal’ granted to the Society in 1911 by King George V (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Society_of_Portrait_Painters ). The Society established its own annual and specifically portrait-focused exhibition, which generally attracted interested press reviews in London and more widely, since a wider audience clearly was attracted to portrait paintings (though perhaps for a variety of reasons). The Society also acted as a contact point for those wishing to commission portraits from its members, a function which seems to have been thriving and well-used during the nineteen-thirties, since the impact of a portrait commission on artistic values is discussed in detail in an article titled ‘Customer and Artist (II) the Royal Society of Portrait Painters’ (by the artist, writer and art critic Jan Gordon, The Observer, 21 November 1937, p.16 – the previous article about the relationship focused on the exhibition of the rejected designs of Duncan Grant for the liner the Queen Mary, 14 November 1937, p. 16). The forty-seventh Royal Portrait Society exhibition of 1938 was reported in The Times as opening at the Royal Institute Galleries, Piccadilly, on 19 November 1938, after which it went on tour. This report, as it did every year, included small images of four or so of the portraits in the exhibition (18 November, 1938, p.20). Most are of celebrities broadly-speaking, including many society people, many titled, together with some theatre folk and politicians, and some relatively ordinary but probably well-heeled citizens. Sadly the 1938 selection does not include the portrait of Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jike, but I take it that it too must have been commissioned by its subject, suggesting that her performance as Mrs Jike was important to her. The Times review of the Exhibition on the following day argued that for some visitors the main interest was in seeing celebrities portrayed ‘irrespective of the merits of the picture’ but also remarked that ‘for a few visitors’ it was the quality of the painting that mattered rather than the personality featured (19 November 1938, p.10). The anonymous reviewer especially praised the work of Augustus John (1878-1961), including his unfinished portrait of the first Labour Prime Minister of Great Britain, the Rt. Hon. J. Ramsay MacDonald. The review of the exhibition by The Scotsman‘s art critic took a similar view of the relationship between commissions, portraits, celebrity chit-chat, and artistic value, but stated it much more stridently:

The social importance of an exhibition of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters is out of all proportion to Its artistic value. To write of it with proper gusto, the art critic would have to adopt the approach of the gossip-columnist, and this critic feels unsuited to the task. This is the most conservative of shows, and many of the three hundred exhibits cannot fairly be judged by modern aesthetic standards (22 November 1938, p. 13).

I am not sure that the portrait of Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jike was necessarily bland, at least, though it may also not have been avant-garde in style – as we shall see James Arden Grant mainly drew and painted in a broadly representative realist mode.

Drusilla Wills (1884-1951) had a long career as a stage actress and made some fifteen film appearances, often in cameo roles, between 1924 and 1949. (1) Her brief obituary in the Stage reported that she had her first stage role in 1902 at the Lyric Hammersmith in the melodrama The Silver King by Henry Arthur Jones and Henry Herman. The obituary remembered her particularly as a ‘capable character-actress’ (9 August 1951, p. 13), and also viewed her performance of Mrs Jike in Love on the Dole as one of her notable roles. Another obituary likewise saw Wills as distinguished by her ‘quaint character studies’ (The Scotsman, 13 August 1951, p.6), while the Halifax Evening Courier titled its concise obituary ‘She Began by Making Herself Laugh’ (11 August 1951, p.4). She indeed specialised in ‘Comedy and Character’ roles, as is made clear by several ‘Disengaged’ and ‘at Liberty’ job-seeking adverts placed by her in The Era (for example, 2 November 1907, p. 4, and 25 March 1911, p. 4). These job-seeking adverts cease after 1913, suggesting sustained demand for Wills in her acting specialism, and indeed from press reviews she never seems to have needed to ‘rest’ again for the next half-century. Reviews from 1904 onwards consistently praise her expertise in character portrayals (Drusilla Wills ‘deserve[s] a word of praise for clever character sketches’ said The Gentlewoman of her performance in Winnie Brook, Widow at the Criterion, 10 September 1904, p.31). On a number of occasions she acted with her sister Alice Wills, in one case playing twins in Yellow Sands by Eden and Adelaide Phillpotts at the Haymarket (as reported by the Daily News 19 October 1926, p. 6).

In 1930 Drusilla even gave a kind of joint interview for the two sister actresses to the Daily Herald about their acting speciality, providing a strong sense of why she might have been proud enough of her work to commission her Mrs Jike portrait:

MY PLAIN FACE IS MY FORTUNE

_________________________________

ACTRESS WHO LIKES TO BE UGLY

__________________________________

MISS DRUSILLA WILLS GRIMACES AT LIFE

___________________________________

BAN ON BEAUTY

____________________________________

DRUSILLA WILLS pulled her dark hair back into a charwoman knot, made a wry face at me, and drew a thin-lipped line across her mouth. ‘There you are,” are said. ‘A plain face, a perfect feel, that is me on stage, and what else could I do with a face like that?’ Miss Wills is the comedienne in The Love Race. Both she and her sister Alice have won laurels on the stage as interfering old spinsters, as young and elderly simpletons, and as lean, aquiline, unmarried women. All the same, Miss Drusilla and Miss Alice are two fascinating actresses. They live in a Georgian flat in Bloomsbury, and they enjoy making their friends laugh about the ‘prettiness’ as they call it, of themselves. ‘I settled down to not-very-decorative looks many years ago’ said Miss Drusilla. “I had been trained for an opera singer by the late Sir Charles Santley, but my throat failed me, and in the way of the very young I decided all was lost.’

‘Then one day I studied my face In the mirror and I said: “Drusilla Wills, what chance have you on the stage with a face like that?” I tried grimaces in the looking-glass and made myself laugh. That is how it began. Both Alice and I often thank our lucky stars that we were not born beauties. I have one pretty photograph that is the joke of my friends. Really, I am a little ashamed of it myself, it is so good-looking (Daily Herald, 2 July 1930, p. 2).

The careers of the two sisters clearly drew on contemporary stereotyping of ‘spinsters’, and prioritisation of a certain range of female appearance, but they turned these prejudices to their advantage in professional terms. We know that in 1908 the Wills sisters, after they had started their acting careers, organised as an act of gratitude with other former and present opera pupils a presentation for Sir Charles Santley to celebrate his recent knighthood (The Stage, 5 March, 1908, p. 10). This suggests their pride in their acting career, even if they had reached it via an indirect operatic route. Alice Wills predeceased Drusilla, dying sometime after 1932 and before 1938 as is clear(ish) from a slightly vague comment in the Daily News (28 March 1938, p. 9) which reported on the film version of the play Yellow Sands, in which Drusilla again featured, but sadly without her sister. The part of Mrs Jike was plainly (as it were) the kind of character part Drusilla Wills had perfected over her long career. Wills did not take the part in the Manchester Repertory production in 1934, nor in the touring production which began that year, but took over Mrs Jike for the Garrick production in London which opened early in 1935. In the Samuel French Acting edition of 1934, the ‘Description of Characters’ says of Mrs Jike that ‘she is a tiny woman with a man’s cap and a late Victorian bodice and skirt. She talks with a cockney accent, having been transplanted from London in her youth’. This was not Wills’ first ‘cockney’ part for as well as many cockney stage parts, she had played a cockney charwoman in the film To What Red Hell in 1929 (directed by Edwin Greenwood, produced by Julius Hagen productions, released 1930 – see Kinematograph Weekly, 31 January 1929, p. 36 and the film’s IMDB entry https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0020507/ ). ‘Character acting’ often, though not quite always, overlapped with playing ‘lower’ class (and thus at this period often ‘comic’ ?) roles. Indeed, Drusilla had played so many servant roles that she was invited to help review new and real designs for female servants’ uniforms in the Daily Mirror ‘Ideal Domestic Dress Competition’ in January 1925:

‘Although I have played many maids’ parts in comedy’, said Miss Drusilla Wills, the actress, ‘my stage uniform has never been so comfortable or becoming as are prize-winning domestic dresses published in The Daily Mirror‘ (28 January, p.2).

She acknowledged though that women actually working in service were the best judges of comfort, practicality and style.

From the earliest reviews of Love on the Dole at the Garrick Wills was praised, though most often as part of the ensemble performance which is at the centre of Gow and Greenwood’s play. Thus the Daily Mirror in January 1935 said that:

Miss Hiller was once more the heroine last night. She was a distinct success in company with such well-known London players as Cathleen Nesbitt, Reginald Tate, Drusilla Wills, Marie Ault and Arthur Chesney. The play portrays life in an industrial town. There is humour, drama and a touch of bitterness – all bearing the stamp of reality (31 January, p.2).

The Stage thought equally highly of the play, the acting and of the contribution of Drusilla Will and her colleagues in the ‘chorus’:

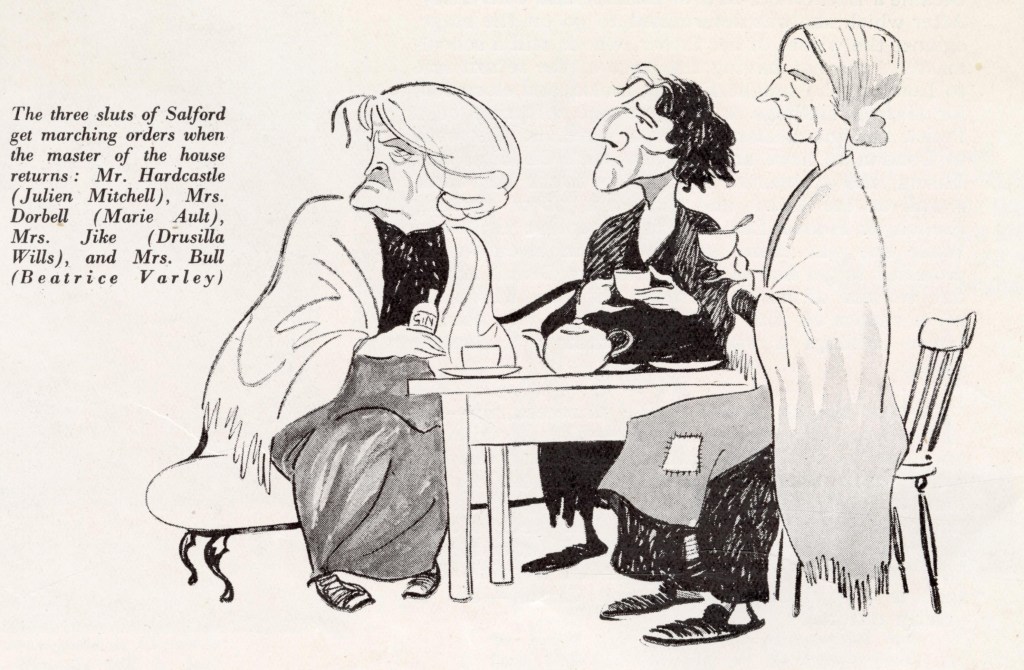

Three wretched old women visit Mrs Hardcastle from time to time for orgies of fortune telling, and, while they are horrible to look at, much that they say and do sends peals of laughter through the house . . . Drusilla Wills, Marie Ault and Beatrice Varley as the three more or less gin-sodden hags who provide the play with its comic relief, are as amusing as they are repulsive (The Stage, 7 February 1935, p. 12).

Just as with the fundamental stereotyping of spinsters, so here there is an underlying ageist prejudice against older (working-class?) women. Nevertheless, I take it that this is a kind of tribute to the character acting in this particular play, and to the specialism of character-acting more widely. In a similar vein The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News observed of Love on the Dole that:

The details do not lack in comedy, and the audience rocked at the sallies of three old cronies (Drusilla Wills, Marie Ault, and Beatrice Varley), who with an air of Macbethian witches discussed the affairs of the world, stating that it had never been the same since the old Queen died and the Albert Hall had been given up to boxing (by Prince Nicolas Galatzine, 8 February 1935, p. 38).

The ‘Chorus’ are never described in the novel or the play as ‘witches’, nor is any reference made to Macbeth, but many theatre reviewers saw the three (there are four in the novel) older women in exactly these terms, though they often differed about whether their main contribution to the play was comic or tragi-comic.

To turn from the subject to the artist, James Arden Grant (1885-1973) was a prolifically productive artist during a long career. He studied before the First World War at the Liverpool School of Art under Frederick Bungo Burridge and Percy Francis Gethin, and at the Académie Julian in Paris under J. P. Laurens. (2) Influenced by these tutors he worked in a variety of painting genres and kinds of paint and drawing media, and was also a print-maker, but was most active and best-known as a portrait painter. He spent periods teaching at art-schools, including his alma mater the Liverpool School of Art, and the London City and Arts Guilds School, and indeed became Vice-Principal of the London Central School of Arts and Crafts. He was a member of a number of societies which supported and promoted different kinds of artistic making, including in addition to the Royal Society of Portrait Painters, the Royal Society of Painter-etchers and Engravers (from 1928 onwards), and subsequently joined the National Society of Painters, Gravers and Sculptors, and the Pastel Society. He became President of the Pastel Society. (3) He also carried out a few advertising commissions often featuring portraits, including for London Transport (‘For London Drama – London Transport, poster, 1935, held by the London Transport Museum, https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/collections-online/posters/item/1983-4-4318) and for Rowntree’s Aero chocolate bars (two different magazine and newspaper adverts, 1955; see material and commentary by Kerstin Doble in the University of York Borthwick Institute for Archives: https://digital.york.ac.uk/showcase/agArtist.jsp?id=elaine§ion=portrait) .

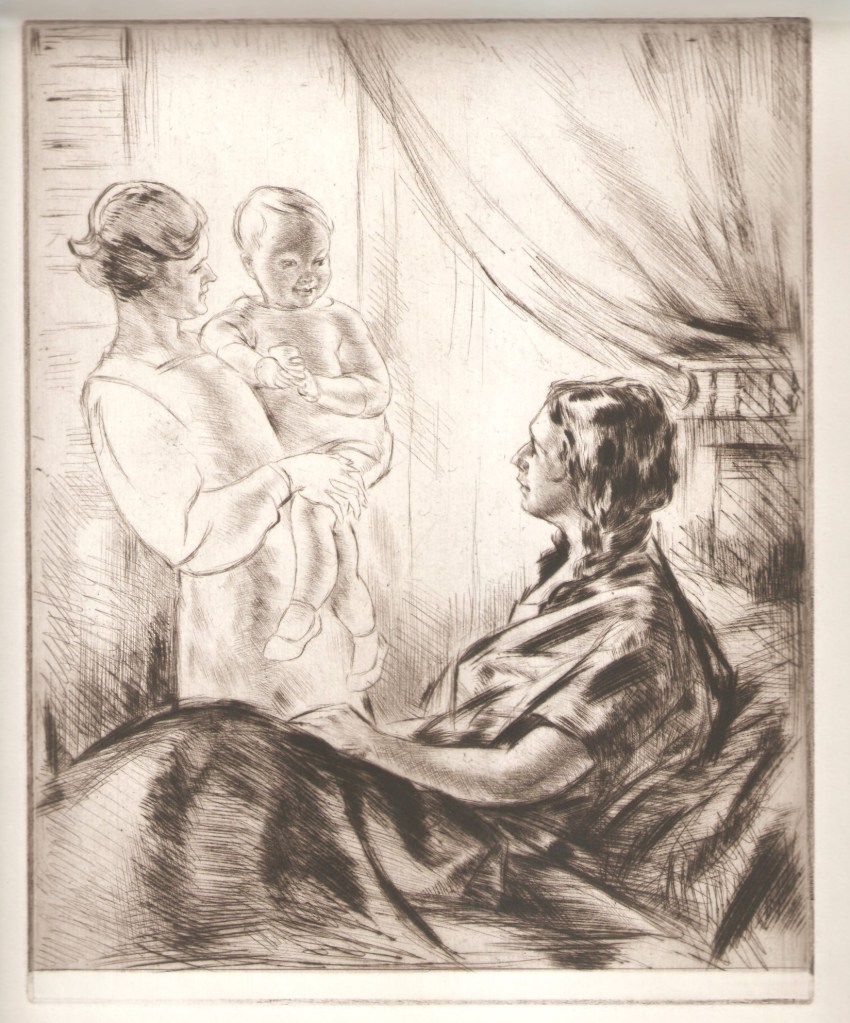

Grant’s work in all genres is now clearly highly collectable, and is frequently sold at British and US auction houses (usually fetching prices between hundreds and thousands of pounds sterling or US dollars). Several several national galleries hold examples of his paintings and drawings including the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, the British Museum, and the V&A. The National Portrait Gallery has four portraits by Grant, all lithographs made between 1944 and (probably) the early nineteen-fifties, and as it happens (?) all of male subjects – though Grant frequently painted portraits of women. Unfortunately (and relatively unusually for the NPG) the licensing details mean that I cannot easily reproduce any of these here, even under an academic licence. However, I do have an etching of my own by Grant titled La Bonjour, which gives a sense of his drawing style (or one of his drawing styles – his work seems to be quite varied).

A large difference between this article and my article about the Wendy Hiller as Sally Hardcastle portrait is that I have not been able to show an image of the Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jike portrait – for the simple reason that I have not found any reproduction of it nor any references to it after its exhibition at the Royal Portrait Society shows in 1938. Indeed, I do not know for certain that the painting still exists. Drusilla Wills had, as far as I can see, no close family once her sister Alice had died: neither sister married. As her Stage obituary tells us, Drusilla died suddenly and unexpectedly aged 66 after she was ‘taken ill in a taxi’. Her place of death was the Homeopathic Hospital at Great Ormond Street, London, though whether she was taken there by the taxi because it was the closest hospital or whether she requested to go there because she believed in homeopathy is not recorded in the account (I have found no other reference to homeopathy in any material about her life, but there is little in newspapers not directly related to her theatrical life). (4)

However, Drusilla seems to have made careful preparations for her estate. She had been active for much of her career in at least three charitable theatrical organisations, the Catholic Stage Guild, the Royal General Theatrical Fund, and the Actors’ Benevolent Fund. She was a committee member for the latter, and was regularly named in reports in the Stage of the fund’s work for retired actors. For example, she is recorded as voting to re-elect the current officers at a meeting reported on 28 May 1936, p. 11, and was still working for the Fund towards the end of her life, sending gifts and greetings for the annual Christmas party at Denville Hall, the Fund’s Home for Retired Actors (the Stage, 5 January 1950, p.9). (5) Her devotion to the Fund continued in her legacy, for The Times reports an auction at Christie’s featuring some valuable fine furniture:

A sale of decorative furniture and porcelain at Christie’s yesterday, which totalled £3, 690 . . . included six Hepplewhite chairs and a pair of armchairs upholstered in floral red damask, which belonged to the late Miss Drusilla Wills, and were sold for the benefit of the Actors’ Benevolent Fund (November 9, 1951, p.6 ).

Given this attention to detail, it seems unlikely that Drusilla did not make some plan for her portrait as Mrs Jike. However, I have found no trace of the painting nor of it ever having been sold at auction. Perhaps it was left to a friend or colleague, and is still out there and treasured somewhere? This article then is something of an empty frame, but we do have a few key verbal descriptions to give us a sense of the portrait’s approach to Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jike. The Leamington Spa Courier described, as we have seen, the exhibition as containing portraits with ‘dramatic and subtle contrasts’ and listed the Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jike portrait as among a group of ‘interesting pictures’. In its coverage the Coventry Evening Telegraph, says ‘There is much character in the picture of Drusilla Wills in Love on the Dole’ (14 April, 1938, p. 16). The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer went one step further in seeing the portrait as verging on the excessive, locating this view in an interesting if partially articulated theory of the aesthetics of portraiture:

Sir John [Lavery] himself appears in a studio portrait by Stanley Grimm (who himself is shown in a lithograph by A. Grant [now in the National Portrait Gallery collection]). Grimm’s Lavery has a companion in the portrait of the Scottish painter. Fiddes Watt. Both have a strong sense of character that amounts almost to caricature, but give decided and definite accounts of the sitters as anything here. The sense of character is carried perhaps to extreme in Grant’s portrait of Drusilla Wills in Love on the Dole. The aim of a portrait is not to fix passing expression, any more than to present the sitter with the petrified expression of a marionette (by A.H.A. ,12 May 1938, p.5).

A.H.A sees too much characterisation in a portrait as introducing the risk of caricature, while admitting that a portrait should not catch just a passing moment in the subject’s expression, nor fossilise them into one posture, but should give a permanent and a lasting sense of their core identity. This may be a difficult balance to achieve, and Arden’s portrait of Drusilla Wells may just go beyond the ideals of A.H.A. It seems likely then that James Ardern Grant’s portrait honoured Drusilla Will’s dedication to character acting in quite a marked way, perhaps bringing out not so much Drusilla Wills herself but Drusilla Wills as that ‘quaint character’, Mrs Jike (who possesses no first name in either novel or play).

I find it hard to believe that after Drusilla Will’s death the portrait was treated like Larry Meath’s books after his sudden death:

One of the furniture broker’s men, a tall, gaunt individual with skin-tight clothes, a luxurious moustache and prominent eyes, came to the door of the house carrying a pile of Larry’s books slung about with a length of cord. He pushed past Sally then dropped the books on to the pavement (Love on the Dole, novel, pp. 216-217).

I very much hope the portrait is still out there somewhere, and might be rediscovered (judging from my own etching and other items for sale, James Ardern Grant often though not invariably signed his work, often on the reverse of the picture, and sometimes added a date and a title). Let me know if you have any information, or, of course, the painting. In the meantime, we will have to make do with what other few images we have of Drusilla Wills, which give some impression of her distinctive appearance as a character actor, and of how she might have looked as Mrs Jike, though of course we cannot know (as yet) how James Ardern Grant interpreted the actress in character mode. The first two are from her film career, while the third would certainly have been considered as caricature by A.H.A for it is indeed a cartoon portrait of Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jikes (from The Bystander review of the play by Vernon Woodhouse, 13 February, 1935, p.8; reproduced with the kind permission of the Mary Evans Picture Library Ltd). Drusilla is drawn together with her fellow chorus members (I think the term ‘sluts’ applied here by the Bystander to the three older women is intended to indicate that they are ‘slatternly’ rather than implying any sexual impropriety). I will be returning to these cartoon drawings of Love on the Dole characters in a future article. I imagine James Ardern Grant’s portrait was at some mid-point between the more-or-less filmic realism and the exaggeration of these ‘sketches’ by Rouson!

NOTES

Note 1. See her useful entries on IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0932639/ and on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drusilla_Wills and on Find a Grave, which gives a comprehensive list of her stage and film appearances https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/214307142/drusilla-wills). She does not have an Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry.

Note 2. See his British Museum entry https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG29617 . There is a brief account of Percy Frederick Gethin’s sadly short life (he was killed at the Somme in 1916) on the Contemporary Arts Society website: https://contemporaryartsociety.org/artists/percy-francis-gethin; Frederick Bungo Burridge in theory has a page on the Campbell Fine Art website, but I have not been able to reach it at the URL given: https://www.campbell-fine-art.com/artists.php?id=30. Like Drusilla Wills, Grant does not have an Oxford DNB entry. J.P. Laurens has a Wikipedia entry (though it advises that the French Wikipedia page on him is superior): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Paul_Laurens. I also cannot find any photographs of Grant, though there was a sketch-self-portrait sold at Olympia Auctions in 2018, of which there is no currently licensable image (see https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/james-ardern-grant-r-e-p-p-s-1885-1973-116-c-68547a0a2e ).

Note 3. See his Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Ardern_Grant , his British Museum entry, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG29617 , and his Art UK entry: https://artuk.org/discover/artists/grant-james-ardern-18871973.

Note 4. The hospital still exists, though with a different name – see the history published on its website: https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/our-services/our-hospitals/royal-london-hospital-integrated-medicine/history-royal-london-hospital-integrated-medicine and its Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_London_Hospital_for_Integrated_Medicine.

Note 5. Denville Hall is still a unique residential home for older people from the theatre industry and profession – see its website: https://denvillehall.org.uk/about-denville-hall/.