1. Who First had the Idea of a Love on the Dole Musical?

Some people find it hard to believe that there was a musical of Love on the Dole – but there really was! As a matter of fact, Greenwood himself seems to have rejected as absurd a proposal he received in the nineteen-thirties that Love on the Dole could be filmed as a musical, according to his fellow-writer, J. L. Hodson, who recorded in his Aberdeen Press and Journal column that:

Our British film magnates . . . have never had the courage or the integrity to deal, so far as I am aware, with a single social problem — (l gather from my friend Walter Greenwood that some genius wanted to turn Love on the Dole into a musical) — and when they made South Riding, an excellent film in many ways, they had not the integrity to stick to the book and falsified and grossly sentimentalised the finish. They have worshipped the box-office . . . slavishly (12 September 1938, p.6). (1)

This may or may not be the same proposal for a film treatment of Love on the Dole which Greenwood remembered with some irritation two years later, as reported by the Sunday Mirror‘s film news columnist Dick Richards:

At last – after seven years – the film of Love on the Dole is under way. Author Walter Greenwood has been up North in search of a leading lady, and I think the search is ended. Censorship, and Greenwood’s refusal to have his play tampered with, have held up production. ‘One eminent film-director wanted me to let Gracie Fields play the part of twenty-two year old Sally Hardcastle’, Greenwood told me, ‘and also to bring in one of Gracie’s famous “cheer-up songs” ‘. Greenwood’s reply was terse, pointed, but quite unprintable (1 September 1940, p. 15).

Gracie Fields (in 1938 aged forty) was a friend of Greenwood’s and had helped him early on – and is not I believe the source of Greenwood’s cross response: it is rather the suggestion of what he clearly thought then the completely inappropriate introduction of musical conventions to his (mainly) tragic and serious story. He had indeed repeatedly stated in the thirties that he would not add a happy ending to his story as the price of a film version, which he might then have thought an alteration bound to be demanded by the musical film genre. I note that in both stories (or both versions of the same story) Greenwood leaves the ’eminent film director’ safely anonymous (though of course I would love to know who it was!).

By the nineteen-seventies, Greenwood’s view of this idea had clearly mellowed – and indeed it was perhaps a suggestion which looked very different forty years after the thirties from how it did during the thirties themselves and before the post-war social contract of 1945. Even so, when the idea of a musical adaptation of the nineteen-thirties sensation Love on the Dole began to emerge (again) in early 1970, there were some who were sceptical about the virtues of the idea. Perhaps in the end there was sufficient general scepticism effectively to suppress what might have been a new era of revival and transformation for Greenwood and Gow’s by then classic drama. The Nottingham Guardian briefly expressed its immediate reaction but did not expand on it: ‘[at Nottingham Playhouse a] world premiere takes on the unlikely task of setting to music Walter Greenwood’s famous play Love On The Dole‘ (10 July 1970, p.14).

The Stage nevertheless did its duty and faithfully reported the forthcoming production with full details of adapters, director, and cast, together with a gentle and highly selective reminder of the piece’s stage history, which gave Wendy Hiller a billing higher than either of its writers:

A NEW MUSICAL. Love On the Dole, based on the book by Walter Greenwood, is to open at the Nottingham Playhouse on July 21 prior to West End presentation. Directed by Gillian Lynne, the cast will be headed by Angela Richards, Eric Flynn, Terri Stevens, Maureen Pryor and Glyn Houston. Love On the Dole has music and lyrics by Alan Fluck and Robert Gray and book by Terry Hughes . . . Sets are by Patrick Robertson, costumes by Rosemary Vercoe and lighting by Nick Chelton. [It] will be produced by David Conyers in association with Jimmy Grafton of Floreat Productions. The well-known play of Love on the Dole was adapted by Ronald Gow, and gave Wendy Hiller her first chance in London, when she became famous overnight. Press representative Roger Clifford Ltd (2 July 1970, p.1).

Alan Fluck (1928-1997) was the innovative music master at Farnham Grammar School (Surrey) and, as well as devoting much energy to developing young people’s opportunities to make music, also contributed to a number of original musical projects. He was a major force behind the idea of Love on the Dole as a musical. The lyricist, Robert Gray, was a scriptwriter for Yorkshire TV, and the author of the book, Terry Hughes (born 1940), was a very successful BBC TV producer and director (regularly producing the Val Doonican show, and shows with Harry Seccombe, and directing a TV production of the musical of Pickwick in 1969). This biographical information about the musical’s creators partly comes from an article in the Manchester Evening News which anticipated the first Stage report (though with additional personal knowledge from interviews with Stewart Nicholls and with Terry Hughes himself).

Terry Hughes was in fact the prime-mover of the project, and it was he who put the adaptation team together – Alan Fluck had been his music master at school and had helped him with hs early career (initially as a singer). Robert Gray was a former BBC colleague. He also approached the director and choreographer Gillian Lynne and judged her contribution to the musical was a major one. Hughes felt there was room for a serious musical which was nevertheless widely engaging and identified Love on the Dole with its elements of tragi-comedy as an ideal story. He had high hopes of a West-End success. Terry knew Greenwood well and found him wholly supportive of the idea, as was Walter’s co-author of the play adaptation, Ronald Gow.

The motivation for the Manchester Evening News‘ article was partly a matter of civic and regional pride. Greenwood’s origin as a Manchester (Salford) writer can be seen in its headline: ‘Walter’s Musical May Come Home’. Even before the Nottingham production got under way, the paper hoped it would move on to a Manchester theatre. It also gave the detail that the musical would have a cast of twenty-five and a twelve-piece orchestra. It included a recent interview with Greenwood which implied that while (for once!) he was not responsible for this adaptation of his own work, he approved highly of the project. The author is reported as ‘cheerfully’ saying:

‘Everything seems to be happening to me this year’. Not only is Love on the Dole becoming a musical, but after two years Sir Bernard Miles will be ready to present my autobiography, There was a Time, at the Mermaid Theatre late this year’ (15 April 1970, p.3).

In fact, when it came to review the production the Stage started with the reservations it expected to have but also confessed to having overcome them, in a full and careful review:

IT WAS AN unlikely notion to make a musical out of Love on the Dole. One would have thought that the singing and dancing would only be flattened by the Depression, or that the Depression would be lifted into a foolish fantasy. But the fusion has come off triumphantly at Nottingham Playhouse. The pawky humour of the Depressive Society of the twenties and thirties is caught with a cheery vigour in a script by Terry Hughes, to wittily evocative music by Alan Fluck and neat lyrics by Robert Gray. And for all the superbly managed choreography of the ‘seventies, the burning spirit of Walter Greenwood’s novel is kept hot. Doing a fast, furious and hilarious number about a youth of eighteen getting at last a pair of long trousers only condemns even more a social system that set three million men scratching around on 15s a week dole money.

The flavour of hard times in Hanky Park is as real as a whiff of Lancashire hotpot, with its be-shawled queues outside the pawnshop, its hope of a threepenny treble coming up on the horses, its yearning for a trip to Blackpool. There is a comic masterpiece of a séance where four women find that there’s nothing like talking to the dead to cheer you up. There are rumbustious ensembles like ‘Who Can You Trust If You Can’t Trust Your Bookie?’ There are poignantly hopeful songs like ‘Beyond the Hill’ and ‘This Life of Mine’ and the Hanky Park theme runs through the show like the tramp of hunger-marchers.

As well as directing with flashing skill, Gillian Lynne sets the hallmark of her brilliant choreography on the production. There is a wistful, splendid Sally Hardcastle from Angela Richards, a spry brother Billy from Neil Fitzwilliam, and a vigorously idealistic Larry from Eric Flynn. Since this street-corner reformer is killed by the end of the first half, trying to head off angry marchers against the Means Test, the show inevitably tends to curve into a dying fall, even though it ends with the street turning out to cheer Sally off. But by then there have been glorious moments from people like Glyn Houston, beaming bonhomie as the bookie who offers Sally freedom at a price, Fred Evans as his lugubrious runner, and from a trio of crones, Lila Kaye, Maureen Pryor and Olive Lucius. The costumes by Rosemary Vercoe have the authentic reek of the period; and the ingenuity of the Lowryesque projections by Patrick Robertson brings the mean streets of Salford vividly to festival Nottingham (30 July 1970, p.15)

The fear that a stage musical’s generic conventions just would not suit a ‘grim’ thirties or would falsify them does seem a reasonable one (and in line with Greenwood’s anxieties in 1938), but perhaps forgets the elements of comedy seen by Terry Hughes and which were already present in the novel and grew in strength in the play version. I agree that the adaptation, lyrics and music all seem strong – though more of that in due course – and that the play’s songs did pick up, in their own styles, some of the key points in the 1935 play. Thus there are comic and ironic songs evoking immediately joyous yet longer-term dubious hope, including the wonderful ‘Who Can You Trust If You Can’t Trust Your Bookie?’, as well as more romantic yearnings for a different kind of life in songs like ‘Beyond the Hill’. The review notes that the story is not reshaped towards a conventional musical romance happy ending – it keeps the ‘dying fall’ structure in which Larry is killed in Act 1 and Sally forced to sacrifice herself for her family by accepting Sam Grundy’s terrible bargain at the end of the story. The review also points towards some shifts from Greenwood (and Gow’s) story though – the street turning out to see Sally off in her ‘triumph’, and the ‘beaming bonhomie’ of Sam Grundy at the end. There were, in fact, some further innovations too, as we shall see. The review also praises the choreography and the use of ‘Lowryesque’ projections as part of the set – a Salford association which oddly enough had not I think been invoked in any previous production of Love on the Dole.

Despite the hopes of the Manchester Evening News, Love on the Dole the Musical did not move to a Manchester Theatre, but it does seem to have had a short run in Birmingham beginning on 1 September 1970 (or at least this was advertised – see, for example, the Walsall Observer, 31 July, 1970, p.15). Most disappointing, though, was that despite the hopes of the producers, no London theatre wanted to take the production. There were some appreciative responses (admittedly including from the production team) after the run at Nottingham had finished, vigorously arguing that the final lack of a London production was a great mistake. These included several letters to the Stage:

SIR, During the 1970 Nottingham Festival, I had the very great pleasure of visiting the Nottingham Playhouse to see the new musical version of the play Love on the Dole. This was a truly wonderful experience. The people of Nottingham were offered a show with a strong story line, excellent dialogue, music and dancing all delivered by a wonderfully lively and competent cast, playing in a set which in itself was a masterpiece. It is not often that one can go to see a show and come away having experienced all that the live stage is able to offer, but this show was one of those rare exceptions. This is the kind of good material that the theatre is crying out for and I am convinced that the show would have been successful in London. Terry R. Massey (10 December 1970, p.14).

This is not perhaps deeply analytic, but does suggest the combination of strong elements in the production. It gave the co-producers a chance too to voice their hopes of keeping the production alive:

Sir, we as co-producers, and all who were involved in the Nottingham Playhouse production of the musical version of Love on the Dole were delighted to read the highly complimentary letter about it that you received recently from Terry Massey. We would like to assure him and many others who have written to us with similar enthusiasm that this musical is far from dead. The only reason why it is not currently playing in the West End is that we have not yet as yet been able to secure the right theatre for it. However, we are confident that we will open in London in 1971, and we recommend Mr Massey and all other enthusiasts for this musical to watch your columns next year for the announcement of our West End opening. DAVID CONYERS, JIMMY GRAFTON, L.O.D. Productions Ltd., 9 Townsend House, 22 Dean Street, W.1 (the Stage, 31 December 1970, p.14).

It does slightly sound as if Terry Massey was a friend or acquaintance . . . but still I have reasons to think that actually the co-producers’ faith in the show was justified. I also note with interest that they put together a company called ‘Love on the Dole Productions’. Terry Hughes’ memory is that there were also some practical obstacles including the lack of a London theatre likely to be free in the immediate future and the lack of a suitable star free to take the part of Sally and to help draw in West-end audiences.

2. The Show Itself

2a. The Nottingham Premiere, 1970

I was around in 1970, but was not really old enough easily to make my way to the Nottingham Playhouse and back from where I then lived in London, so I have no direct experience of this production. There was though a very full eight-page programme which gives us a great deal of information about the production, of which Stewart Nicholls (see below) has kindly sent me a copy. Like the set projections the cover of this drew on an L.S. Lowry design based on his 1930 painting Coming from the Mill but reproduced in monochrome on a pink background (the same painting in full colour was used by the German translation of the novel of Love on the Dole over a decade later, in 1983). It gives a wholly appropriate sense of Salford’s workers coming home from work through the industrial landscape of the city.

Full details of the musical’s writers and production team are given inside on the first page, which also makes clear the invaluable help of national and local funders.

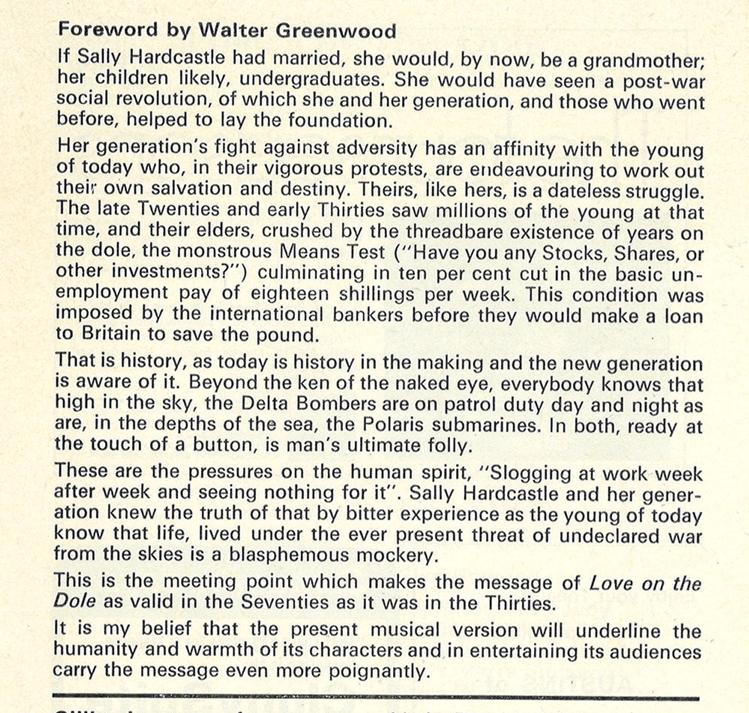

The second page had the coup of a foreword by Greenwood himself, then in his sixty-seventh year. He did not see the continuing relevance of his story at that point as so much about unemployment in itself, though he gave a concise account of that, but instead suggested that the modern context of nuclear war and MAD (mutually assured destruction) was its equivalent for young people in hanging like a blight over anything like a normal life (for a fuller discussion of this see Walter Greenwood and the Delta Bombers *). In the final paragraph he expressed his approval for the musical version as well able carry the spirit of Love on the Dole, and like its previous versions, to use entertainment to create empathy and to make serious points.

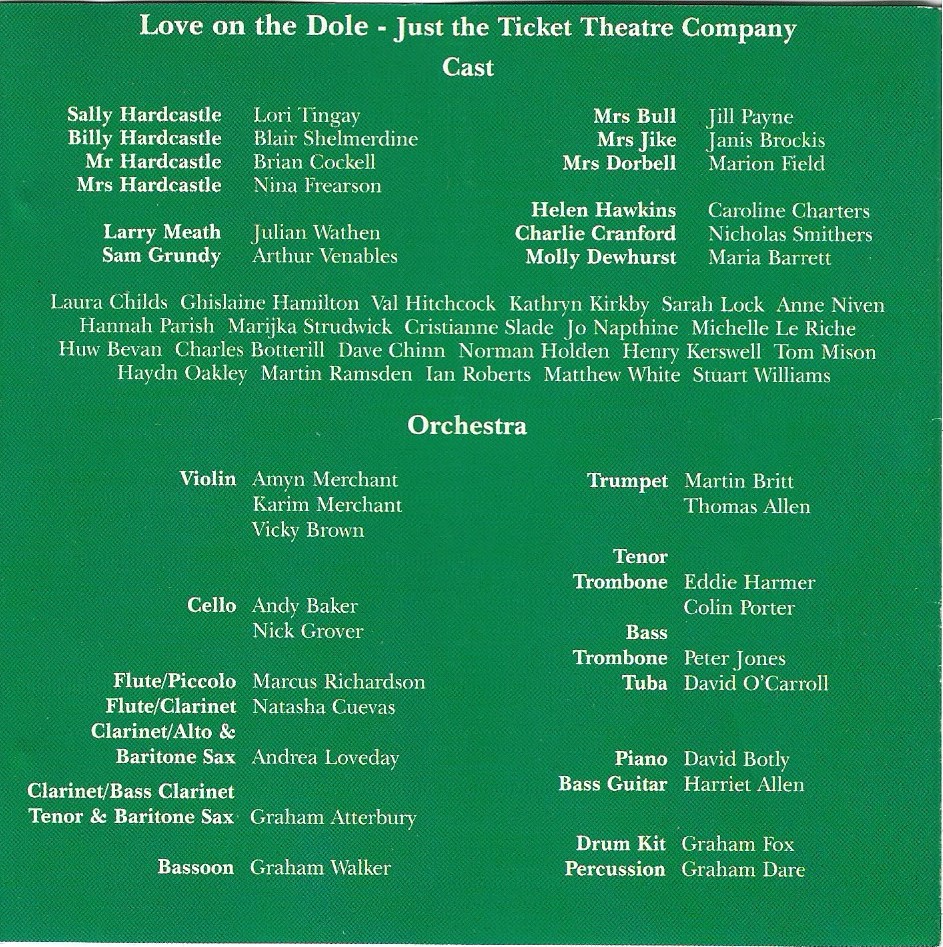

The third page gives the full cast list, including the large ‘chorus’ of neighbours.

2b. The Woking Revival and the CD, 1995

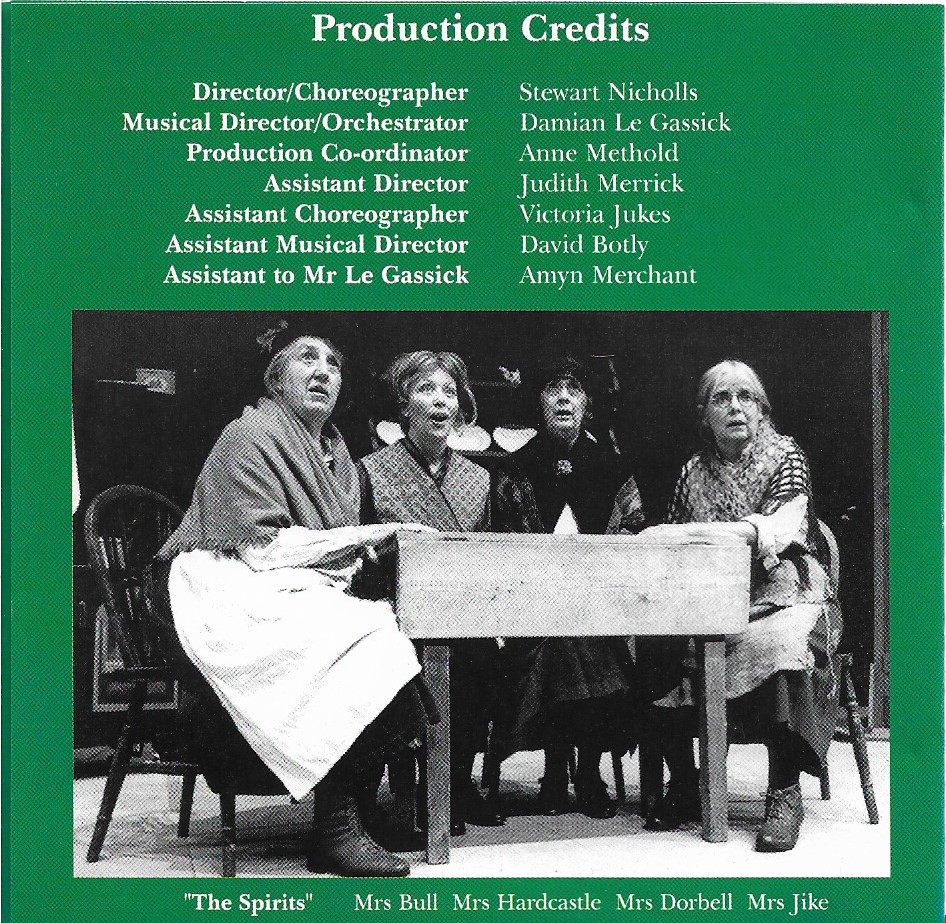

However, there was one revival of the musical of Love on the Dole of which I have at least some experience. In 1995 there was an (accomplished) amateur premiere/revival of the play at the Rhoda McGaw Theatre, Woking, by the ‘Just the Ticket Theatre Company’, directed and choreographed by Stewart Nicholls. Among many other things I am very grateful to Stewart for giving me permission to reproduce here some key tracks from the CD so that readers of this article can get a real sense of the musical and dramatic qualities of this adaptation of Love on the Dole (Stewart Nicolls of course retains the copyright of these clips).

When I was working on my book on Love on the Dole during 2017 I was luckily able to locate and contact Stewart Nicholls who very kindly sent me this copy of the CD the company had recorded (I often listened to it while writing my book, in fact). This means that I can at least respond to and discuss the book, lyrics and music of the musical of Love on the Dole, even if I cannot talk about the full production and choreography (and there was a good deal of important movement in both the Nottingham and Woking productions). I hope that the critical attention is also a thank you and tribute to Stewart Nicholls and everyone else who performed in and contributed to the revival production, as well as to the original authors of the musical Love on the Dole. In short, I am lucky enough to be one of the rare audience members for a performance of the musical of Love on the Dole, even if only for its aural without its visual elements. (2)

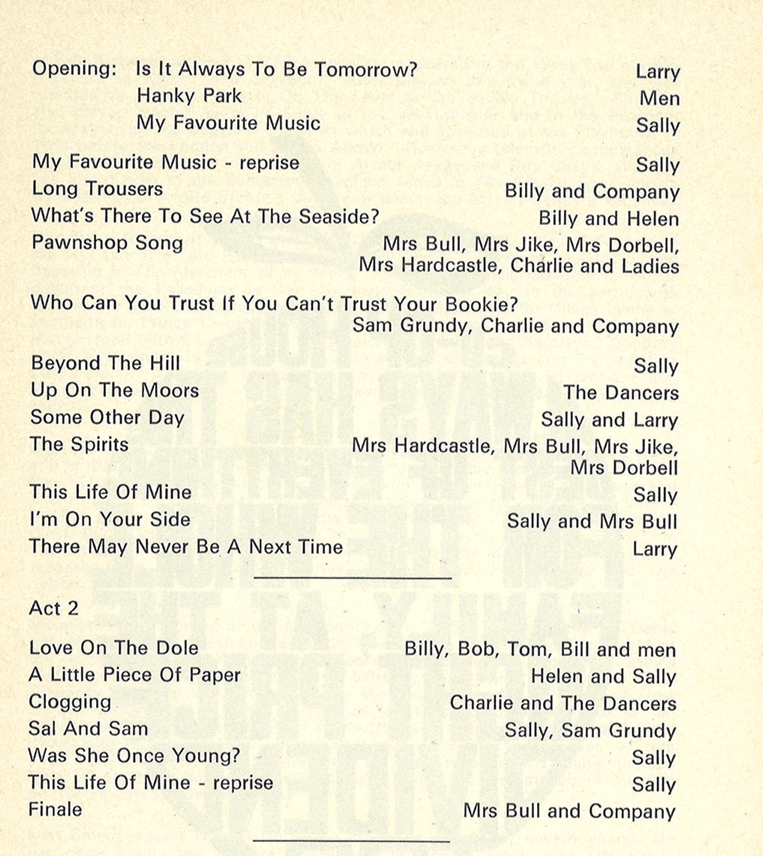

Below on the rear cover of the CD is the complete list of numbers which translate Greenwood and Gow’s work into a musical. These titles let us see some of Terry Hughes’ adaptation decisions in terms of the architecture of the plot, and also of course Robert A. Gray’s decisions about the local verbal and dramatic texture of the piece.

Act I

The first number, ‘Hanky Park’, as one might expect, is a chorus giving a collective introduction to the experience (or anyway male experience) of Hanky Park. After a declamatory brass and drum introduction the male chorus stolidly sing as if it was an unalterable fact of life : ‘I was born and bred in Hanky Park’. This quickly switches to a dialogue in which Larry challenges the mass of the men, saying they could change things with their collective votes, which one man loudly doubts, while another says that things will soon change for the better. Larry then launches into a solo asking if they are prepared to wait for ever for the things which make life worth living, and for things to turn the corner: ‘Is It Always To Be Tomorrow?’.

Larry argues in song that they depend too much on belief in a deferred happiness even if it never arrives: ‘You’re a prisoner of the present, and you’re a prisoner for life, its not just a prison for you but also for your wife . . . you keep reaching towards the future when there are so many things you should have right now’. The men respond with a stubborn repetition of ‘I was born and bred in Hanky Park’. This opening scene concisely sets up through lyrics and musical form the men as putting up with whatever and Larry as an individual and dissenting voice – though also one which is not listened to?

Mrs Hardcastle then enters saying that Larry can certainly talk but that she doesn’t always understand what he is saying – does Sally? She says not all of it, but she knows from the sound of his voice that what he says is good, exciting, new, and different. She then breaks into the song ‘My Favourite Music’, which expresses her feeling that she could listen to him all day, because his voice is her favourite music. This response from her to Larry’s voice develops in a form specially suited to a musical her original liking in novel and play for Larry’s [self-educated] voice and language. The male chorus re-enter beneath her line restating the only thing they know – that they were born in Hanky Park – while Larry also sings beneath her line restating his desire that some things be achieved today and not waited for till tomorrow!

The next song (number 2) is a quartet from Sally, Billy, and Mr and Mrs Hardcastle about Billy’s vital need for some adult clothes to replace his ragged schoolboy’s garments (I should point out that the character called Harry Hardcastle in all previous versions of Love on the Dole is here re-named Billy Hardcastle – I think to avoid what the adapters saw as a potential confusion with Larry). In production this song was preceded by dialogue which made it clear that Billy was in a desperate plight as the only local lad with no adult clothes to wear at all, so that a serious context was in place before what might seem the relatively upbeat lyrics and tune of the song. The long trousers are seen in the song as motivated partly by the need for Billy to be more attractive to girls, but the fact that in his current worn-out clothes, he isn’t, as he says, fit to be seen in the street is already established.

The third number is ‘Move Yourself Horse’, which is about Billy’s weekly ‘thrippenny treble’ bet with Sam Grundy. He and Helen (with the chorus of boys and girls) fantasise joyfully about being able to go away on holiday from Hanky Park on the winnings – even to Blackpool! They sing hopefully, with a clever play on the verb ‘riding’: ‘Move on horse – there’s a lot more than a jockey riding on you!’ and adding ‘Stir Yourself nag!’ The short fourth number takes us to ‘The Pawnshop Door’ where Mrs Bull, Mrs Dorbell, Mrs Jike and the women’s chorus sing to a slippery dance-like tune that the pawnshop door is always open, waiting like a spider’s web to trap the fly inside. Mrs Bull advises, in speech not song, to take in more washing – anything to avoid the pawnshop.

The next longer number is linked by being again about another source of ‘support’ and ‘hope’ in Hanky Park: betting. Sung by Sam himself, his sidekick Charlie and the chorus of men, this is one of the songs praised by the Stage review – ‘If You Can’t Trust Your Bookie’. The song (self)advertises Sam’s absolute reliability and alleged self-sacrifice in the interest of his punters: ‘he can scarcely scrape a living, but his reward is giving you your prize’. This is sung to a trombone accompaniment just as slippery and off-beat as the pawnshop tune: ‘if you can’t trust Sam, you’re just not the trusting kind!’.

The sixth number is also linked in focusing on Sam’s self-assured and allegedly indispensable reliability as he assures Sally in a disarmingly attractive melody that ‘You’ll Never Get Out Without Me’: she is in ‘Poverty Row – a prison that won’t let you go’. Sally however contradicts him in dialogue saying she’ll escape but with Larry and never with Grundy. Sam says she is wasting her time with that ‘dreamer’ and repeatedly contradicts her by singing his phrase ‘You’ll Never Get Out Without Me’.

The next song (number 7) stays with what we might call the con-artists of Hanky Park in letting us listen in on one of Mrs Jike’s séances. To another jaunty but spooky tune again with prominent brass, Mrs Jike builds the atmosphere and invokes the spirits: ‘Is there anybody there? Knock thrice for yes and twice for no’. Three knocks are heard. In a new joke since the play Mrs Bull queries how the spirits could ‘bloody well knock’ if they weren’t there?, but is told to show more respect. As in the play, there are important questions to be put to the dead – about the Irish Sweepstake – and messages to be sent – Mrs Bull tells Jack Tuttle she relieved him of the ten-shilling note he had clenched in his hand when he died so not to worry about it. Mrs Bull also asks the spirits if Mrs Jike can afford to pay her back the half-crown she owes her – there are two knocks and then a mysterious third knock is added and Mrs Bull demands her money! [again, this is an original joke new to this adaptation]. The séance ends with a blast of brass and the music changes for the next song (number 8), ‘That Clock’, which is Sally’s. The song builds on Sally’s indignant exit from the séance in the novel and play and also on her vow not to end up like her mother, exhausted by her poverty-stricken life, at the end of the film adaptation, but is nevertheless new in its verbal expression of these ideas through the idea of the ever-ticking clock at this point in the story. She sees and fears that her life is ticking away towards an unsatisfied old age, but before that she ‘wants to live!’. Sally sings that Mrs Jike is herself a ‘walking warning’ of the future: ‘dirty, shabby, living for nothing but swigs of gin and pinches of snuff’. Meanwhile, ‘that clock is telling me get up and live today!

The next number, is a duet ‘I’m on Your Side’ between Mrs Bull and Sally, where Mrs Bull makes plain that she will help Sally and that she thinks Sally and Larry will escape together from Hanky Park. Invited by Mrs Bull, Sally joins in the song, ‘Isn’t it a friendly phrase, I’m on your side?’. The last number of the First Act follows, with Sally and Larry singing the duet ‘I Don’t Give Up Easily’. This is a romantic tune but Sally and Larry take rather different elements in the lyrics. Sally sings that she doesn’t mind what she gives up as long as she has Larry, and that she is tough and won’t give up, while Larry at first sings that it might just get too tough, and that she might more easily get out of Hanky Park on her own. Finally though they agree in the last lines of the song that ‘they will see each other through’. Larry adds in dialogue – and reinforcing his dissident voice – ‘I’m not getting married in Church, it’s Registry Office or nothing’, to which Sally consents. The Act then closes, however, with an ominous version of the opening Hanky Park theme, with more brass and drums added, before ending with a gentler but still melancholy restatement of the theme.

Act II

An ‘Entr’acte’ piece (number 11) repeats in a lively setting Larry’s Act I ‘Is It Always to be Tomorrow?’ theme before segueing into a more ominous repetition of the ‘Hanky Park’ theme, though this time with lyrics about how the boys’ apprenticeships quickly lead to redundancy, rather than jobs for life. Next comes the song ‘There May Never Be a Next Time’ (12), another duet between Larry and Sally, in which Larry insists that he must lead the Means Test protest march. It is followed by a reprise of ‘Is it Always to be Tomorrow’ (number 12) sung by Mrs Bull and the chorus of men and women. Song number 14 is about how much a marriage licence means despite being just a ‘Little Piece of Paper’ and is sung first by Helen in her biggest number: ‘It is nothing much to look at but you treasure it all your life’, before being taken up first by Sally and then by Larry. Nevertheless, the song ends with Larry singing the word ‘never’, and it seems to mark the falling apart of their plans and the death of Larry (though this could be clearer – it probably was in the production). Certainly by the next song (number 15), Mrs Bull’s ‘Beyond the Hill’, it is clear that Larry is no more and Mrs Bull advises Sally to get out of Hanky Park to ‘another world I’ve never seen, beyond the hill, nor ever will, but you have a chance to see it for me’.

Number 16 is the account by Mrs Bull, Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Jike of how Sally has indeed decided to get out of Hanky Park by taking up Sam Grundy’s proposition. The vigorous song given as a trio does something to tackle the queasiness which many thirties and forties audiences might have felt about the terms of this deal (essentially sex for money) by predicting that actually Grundy will be given a hard time by Sally who will exercise her power over him and teach him a lesson; he’ll have got ‘A Tiger by the Tail’: ‘She’d battle him, bite him, bite him, tooth and nail, he’d never know what had hit him . . . She really would be a reason to rejoice, our Samuel would regret his choice’.

In this re-imagining Sally would turn the tables and Grundy would become her victim – and give all the women of Hanky Park reason to celebrate a victory. Curiously in a short story sequel to Love on the Dole which remained unnoticed by critics Greenwood himself also imagined that to be one of the consequences of Sally going to live with Sam Grundy (see What Sally Did Next: Greenwood’s Sequel to Love on the Dole (‘Prodigal’s Return’, John Bull, January 1938) ).

In song number 17 Sally connectedly reflects on the cost women in particular pay for the life they have to lead in Hanky Park: ‘Was She Once Young?’. The song with a meditative and lyrical tune reflects especially on her mother’s life: ‘deep in her eyes a look of despair, deep in her face a life of care, was she once young, was she once pretty, was she once dreaming dreams, once dreaming of living life, before the mother, before the wife?’. This theme derives partly from the final scene in the film version of Love on the Dole, where Sally says that now Larry is dead she’ll not let any man make her like her diminished mother now, and partly builds on the musical’s own elaboration of this idea applied to Mrs Jike in the Act I ‘That Clock’ song (number 8).

Mrs Bull leads the ‘Finale’ (number 18) which is a gentler, more lyrical reprise of number 9 from Act I: ‘I’m on Your Side’. Towards the end Sally speaks to Mrs Bull, saying ‘I wish you were going with me’ to which Mrs Bull replies, ‘I’ll be with you every step of the way’ before singing a reprise of ‘Beyond the Hill’ (Act II, number 15). The whole company and orchestra conclude the show with the ‘Finale Ultimo’ (number 19) which is a further reprise of ‘Beyond the Hill’, making the final point that there IS/WAS a different, better, future life for the people of Hanky Park which has been achieved (or shall we say partially achieved?) by 1970 (and 1995).

The musical of Love on the Dole may in its own way (like the film) put the thirties into a longer perspective – and hence can afford to be a little more upbeat and optimistic than Greenwood’s original novel, and even than Greenwood and Gow’s play. Maybe Greenwood was right to be huffy about a musical in 1938 and also right to be be more relaxed and indeed positively pleased about the idea by 1970?

The musical adaptation does introduce some noticeable innovations into the narrative of Love on the Dole, mainly with the effect of altering the emphases of the original[s]. Some things follow the play – there is no room for the villainous Ned Narkey on stage – but other alterations shift balances. Mr and Mrs Hardcastle have reduced roles in the musical compared to the play, while Sally’s part, already more central in the play than in the novel, becomes more central still here (she sings solo in two numbers and jointly in another seven numbers out of nineteen). She is also to an extent transformed at the end from self-sacrificing if feisty victim to an agent of vengeance for all the women of Hanky Park. There are potentially feminist elements in Greenwood’s novel and the play, but in the musical these are bought out with considerable strength. In a related vein Mrs Bull emerges from the trio of older women as a positively leading role (she sings in seven numbers out of nineteen, and has significant solo passages in at least four), taking finally the role of spokeswoman and community champion for Hanky Park, and particularly its women – present and future – and for escape for all from its clutches.

I ought to say that the 1995 revival – the only one we have in something relatively close to a record of a full performance – was not identical to the 1970 production, as Stewart Nicholls tells us in the CD booklet: ‘ [it had] much revision, some new songs and new orchestration’ (the music for the new songs was though still composed by Alan Fluck). Some of the variations in the numbers can be seen from the original Nottingham programme which on its fourth page listed the numbers in the original show. Some numbers from Nottingham are not in the Woking revival (or not on the CD version anyway), including ‘What is There to See at the Seaside?, and two dance numbers ‘Up on the Moors’ and ‘Clogging’. This may be because insufficient dancers were available – the dance numbers had received considerable praise in the original Nottingham show:

They do a clog-dance in Love on the Dole – a precision-built clickety-clackety showstopper that is a dance of triumph for this marvellous musical which had its world premiere last night (Emrys Bryson, Nottingham Evening Post, 22 July 1070, p.12).

However, in the Woking CD are several new numbers including ‘Move on Horse’, ‘I don’t Give up Easily’ and the important ‘Tiger by Its Tail’ in Act II.

Even without the stage elements, the CD recording does give a more or less full sound performance and, as the CD booklet also tells us, received the blessing of the 1970 authors and director so that it in the genealogy of the first production: ‘the show was warmly received by both the public and members of the theatrical profession – including the original director and choreographer, Gillian Lynne [and received support from] the writers Alan Fluck, Robert A. Gray and Terry Hughes’. The music of the 1995 revival seems to me fully in the spirit of the musical genre and follows Alan Fluck’s command of that tradition: most of the numbers are upbeat and dance-like, but capable also of more romantic and more melancholy sequences. The orchestration may not have been identical to that of 1970 (in fact it looks as if the orchestra was larger in the revival), but certainly was based in a pretty full orchestral resource, with strings, woodwind, saxophones, brass, a piano, an electric bass, a drumkit, and percussion, as the CD booklet tells us (together with the names of the full cast):

Conclusions

My overall conclusion is that the musical was a very fully thought-through and creative response to the previous versions of Love on the Dole, and did deserve a wider audience and a longer run. The songs together with a small amount of dialogue tell the story and sustain the drama of Love on the Dole very concisely. Both through Terry Hughes’s version of the plot and through Robert A. Gray’s rhyming couplet lyrics I think this adaptation is impressive, as is Alan Fluck’s musical score. Let us hope at some point for another revival and a newly creative response to this highly interesting musical adaptation of Love on the Dole. (3)

NOTES

Note 1. This comment was made in a column called ‘Please Let Me Have My Three Loud Growls’, in which Hodson laments the quality of British hotel food, the standards of the film industry and the reluctance so far of the Government to create a ‘National Register’ of skills in case war breaks out. J. L. Hodson (1891-1956) was a Lancashire writer and journalist, best known in the thirties for his novel and then play adaptation about the Depression, Harvest in the North (1934; 1935). His work was quite often compared to that of Greenwood. His Wikipedia entry eccentrically makes no reference to his pretty famous work from the nineteen-thirties, concentrating only on his (also interesting) work from the Second World War and after.

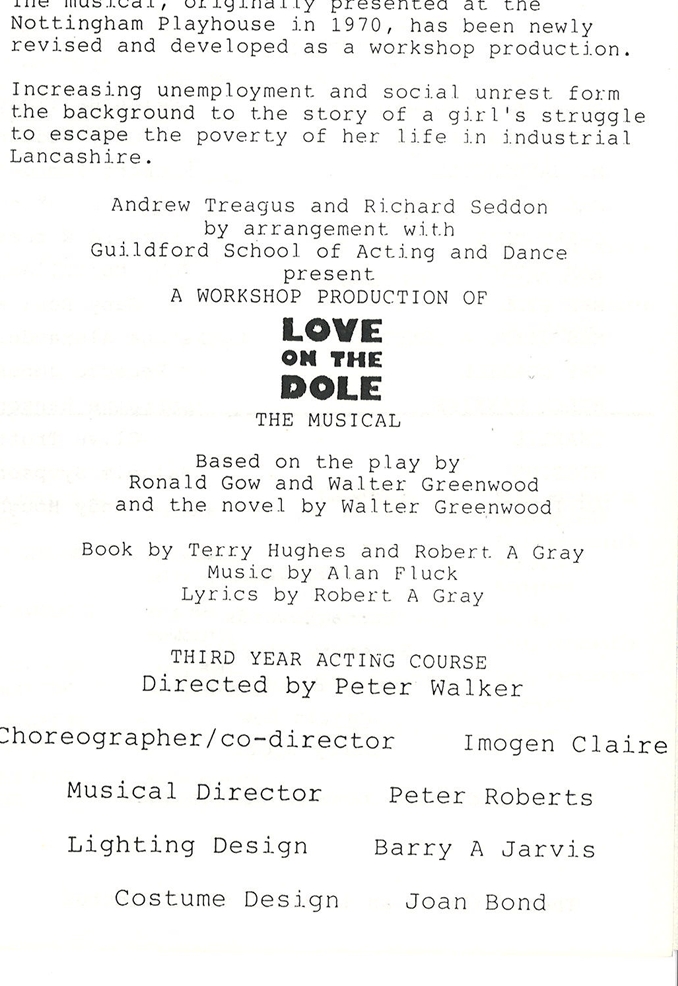

Note 2. For an account of Stewart Nicholls’ career as a director of musicals see https://narrowroad.co.uk/creatives/stewart-nicholls. I am also very grateful to him for an invaluable recent conversation via Teams on 4 December 2024 when he was able to give me a great deal of additional information about both his 1995 production and about the original Nottingham Playhouse production, as well as another 1980s production at Guildford School of Acting at the University of Surrey (a drama school curiously enough established in 1935 – the year when the play of Love on the Dole was first performed at the Garrick Theatre, London). I know less about this production but pages of the programme listing key personnel are posted at the end of this note below. In addition Stewart generously introduced me to Terry Hughes who did me the great kindness of letting me interview him over the phone from his home in Los Angeles (11 June 2025). Both Stewart and Terry recalled that Phillips Records made a sophisticated recording of the musical with the Nottingham cast, and it also had some additional songs to those sung in the actual performance. It was not released, but recordings may still exist, and if any of these ever come to light I will be delighted to add an account of their interpretation of Love on the Dole: the Musical. In the meantime I am immensely grateful to Stewart for permission to reproduce the tracks from his CD – this properly transforms a discussion only in words into a discussion in words and music, the appropriate way to talk about a musical.

Note 3. I am grateful to one of the anonymous readers of my book (Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole – Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, 2018) who drew my attention to the musical adaptation, a suggestion which I have (at last) followed up in more detail in this article though it took some eight years.