Well, no, there were no animated film realisations of Love on the Dole in 1935 (though, copyright issues permitting, of course, there still could be one in the future – I hope a suitable creative artist or team of creative artists might be tempted). However, there were a number of cartoon or caricature or anyway sketch realisations of the key characters/actors due to a peculiar reviewing practice by several stage periodicals during the nineteen-thirties. The Tatler, the Bystander and Punch all published quite thorough reviews of new theatre productions, but accompanied each with a set of black and white drawings of the main characters as played by the actors in each production. These varied in style from what I think can be properly labelled caricatures to others which might be called sketches or illustrations.

The Bystander published its illustrated review of Love on the Dole on 13 February 1935 (p.8), with the review signed by Vernon Woodhouse and what it explicitly calls ‘sketches’ by Rouson, of which there are four (I think actually these have elements of caricature in, nevertheless). Punch (or the London Charivari) published its illustrated review on the same date (p.189), with two illustrations signed by G. L. Stampa. The Tatler published its illustrated and double-page review a week later on 20 February 1935 (p.22), with five illustrations which I would certainly call caricatures by Tom Titt, whose pen-name was derived from the name of an English bird which captivated him in an early nature film of 1910 which he saw in his home-city of Warsaw (see below). Across the three reviews this gives us not only the texts, but also eleven original graphic responses to the play, its themes, its characters and their actors. In this article I will look at how the three reviews responded verbally to Greenwood and Gow’s play, and at how the illustrators saw it through their drawing. I presume both verbal and graphic reviewers attended the play, and probably the same performance – that certainly seemed to be the case for Tom Titt and the reviewers he worked with – and I wonder if in general critic and cartoonist discussed their reactions in the interval or afterwards? (1)

I should perhaps begin though by defining ‘cartoon’, ‘caricature’, ‘sketch’ and ‘illustration’, terms which I have already used, with the implication that they indicate differing approaches to the visual elements in these reviews. OED defines ‘cartoon’ as covering several distinct senses. The first and oldest usage (sense 1), dating back to the seventeenth century in Britain, referred to an artistic technique for using a large sheet of stiff paper to lay out a design at the intended final scale for a painting or a tapestry (indeed, the word ‘cartoon’ derived from the Italian word for paper, ‘carta’). The most recent sense (2b) OED defines as referring to ‘an animated cartoon’ in the field of cinematography (the sense I played with in the opening sentence of this article), and records its first usage as going back to 1916 (in the US). However, it is OED sense 2a we are most concerned with:

A full-page illustration in a paper or periodical; esp. applied to those in the comic papers relating to current events. Now, a humorous or topical drawing (of any size) in a newspaper etc.

OED dates the first usage to 1843 and indeed specifically associates it with Punch, citing the periodicals announcement of a novelty in which it would be referring to Parliamentary business in ‘several exquisite designs, to be called Punch’s Cartoons’. It is nice therefore to be able to see this genre still at work in Punch over ninety years later. The broad term of cartoon does then seem to apply to all of our Love on the Dole review drawings in that they refer both to the play as an aspect of current events and to the highly topical social situations which it represents. I think we could add that all the drawings are to a degree ‘humorous’. They do not all, however, have the brief self-contained captions or in-image text which most political or topical ‘cartoons’ include, though longer captions with a different purpose are provided for several.

The term ‘caricature’ has elements which make it more specialised than the word ‘cartoon’, though in practice the two are often associated. OED sense 1a. gives us the key emphasis on exaggeration (dating this usage from 1827): ‘grotesque or ludicrous representation of persons or things by exaggeration of their most characteristic or striking features’. Some of our drawings certainly draw on this tradition. ‘Sketch’ again conjures up a rather different kind of drawing. OED defines the term in sense 1 as first meaning from the later seventeenth century onward a ‘rough drawing or delineation giving the outlines or prominent features without the detail esp. one intended to serve as the basis of a more finished picture’. However, it adds to that sense a later usage which better if not wholly captures the meaning we need for the Bystander drawings: ‘a drawing or painting of a slight or unpretentious nature’. The examples of usage given are mainly eighteenth or nineteenth century, and while most follow the implication that a sketch is ‘slight’, a few suggest that it is the provisional nature of sketches which gives them a positive visual quality of their own appropriate to some contexts. Indeed, Rouson’s own use of the term for his drawings might particularly imply that he had drawn them rapidly, perhaps actually during the play’s performance, so that they have the virtue of immediacy.

Finally, OED can help us with what may be the more general word ‘Illustration’. Interestingly the earliest English uses of this word (from the fifteenth century) in sense 1 have a clear religious meaning in which the ‘illustration’ is provided by divine light, which evokes the word’s origins in a Latin verb meaning to ‘light up’, but in modern English the commonest usages (senses 4a and 4b) are metaphorical developments from that. An ‘illustration’ is defined as ‘the pictorial elucidation of any subject; the elucidation or embellishment of a literary or scientific article, book etc by pictorial representations’. ‘Illustrations’ in the plural are perhaps much more literally (and rather circularly) defined as ‘an illustrative picture; a drawing, plate, engraving, cut or the like, illustrating or embellishing a literary article, book etc.’ In each of these definitions the original sense that illustration casts further light on a topic is still there, and what light is cast on Love on the Dole by these review illustrations is, of course, at the centre of this article.

Let us take our first look at the overall appearance of the three illustrated reviews (a genre term I have just coined) before zooming in on the details, verbal and pictorial, of each in turn and then in comparison. Here are small-scale visual overviews of each review in this order: Bystander, Punch, Tatler. We can immediately see that there are differences in the style and approach of drawings across the three periodicals, including their layout and placing in the text, though there are also similarities – we will come back to both similarities and differences.

(Permission to reproduce the pages and details thereof from the Bystander and the Tatler have kindly been granted by the copyright-holder The Mary Evans Picture Library. The Punch page has been downloaded from the Gale News Vault in accordance with the Terms of Use which permit for educational purposes ‘display and use of reasonable portions of content’).

The Bystander review sets a positive and rather informal tone from the start with its headline ‘ A Champion Show an’ All’. This conviviality continues in the opening paragraph in which the reviewer says he will adopt the device employed by the famous travel guide Baedeker of rating attractiveness of places with one, two or three stars (Vernon Woodhouse might have been pleased that this convention has indeed been adopted by all modern theatre reviewers in newspapers, if often with a five star scale). (2) He gives the play of Love on the Dole his maximum three stars, but immediately warns that the play will not please everybody. At this point while the style remains easy-going as if treating the review reader as a friend, there is something of a change of tone as the review introduces some serious issues about theatre-goers, the purpose of theatre and contemporary social issues of great importance:

I’m not saying this play is everybody’s meat. It wouldn’t suit the sort of playgoer who says ‘We know that such people exist, but we don’t want them brought to our notice’. For here Ronald Gow and Walter Greenwood . . . not only see that these Lancashire characters are brought to your notice, but make sure that you won’t forget them in a hurry.

The sentence implies that such a topic should be treated in the theatre and also judges this play itself to have made its subjects so vivid that dismissing them from your attention will be hard to do. The next paragraph indeed applies a ‘test’ based on the reviewer’s conception of a theatre-goer with ‘normal’ feelings:

I defy anyone with average feelings to see this play . . . and remain unmoved at the gallant fight which is being made in the Hardcastle household to preserve both home and self-respect. I defy anyone to say that the solution of the problem, so far as this particular family is concerned, is worthy of censure.

This makes some key points about how the play should be read (and indeed many other reviews did make similar points). Firstly, the reviewer wants to remove any suspicion that the Hardcastles are ‘thriftless’ and have brought their poverty on their own heads by economic mismanagement and ‘working-class’ vices such as gambling and drinking (accusations traditionally favoured by some middle-class commentators). No – the Hardcastles ‘fight’ to keep themselves respectable, but simply cannot succeed given the waves of inescapable economic disasters which hit them. The next sentence boldly introduces the ‘censure’ issue, which is about the play’s desperate resolution in which Sally feels she has no choice but to become Sam Grundy’s mistress in order to rescue her family from an ever-worsening crisis likely to end in complete destitution (see Sam Grundy’s Car: Sally Hardcastle’s Resistance (1933;1941)*). A few letters to the press did denounce the behaviour of the play’s heroine Sally (mainly written by clergymen, though that is not to say that all clergy received the play badly – on the contrary – see Love on the Dole and the Clergy * ). However, most reviews and audiences saw her actions as the unavoidable consequence of the logic of the narrative, and indeed of the underlying reality, though theatre managements did usually warn that some patrons might be shocked by some aspects of the play, and also said that it was suitable only for adults and young adults over the age of sixteen. Woodhouse points out that one of the family in the play, ‘Father Hardcastle’, does censure Sally, but cannot himself provide any other way of making a living. The review argues that in this tragic situation there was no other way forward.

Having faced head-on aspects of the play which some audiences might find uncomfortable, the review turns from its themes to the cast and their performances and finds everything to praise. Though Woodhouse has seen some of the actors before, a number are completely unknown to him (and he implies to London audiences in general):

There are some artists, previously unknown to me, in this cast who are so good that to associate acting with them seems out of place. Julien Mitchell as the father, Alex Grandison as his eighteen-year old son, and Beatrice Varley as a friend of the family [Mrs Bull] do not appear to be playing parts – they are the people themselves.

This sees some performances as particularly naturalistic and authentic-seeming, perhaps especially because the actors have no pre-existing theatrical personas in the West End. However, Woodhouse is careful to say that actors better known in London also put in convincing performances:

Cathleen Nesbitt gives a beautiful performance . . . as does Ballard Berkeley as Sally’s lover, while we all know that Marie Ault and Drusilla Wills would not let any author down.

Nevertheless, he ends the review with the greatest praise for an actor wholly unknown in London, and whose initial rise to stardom was indeed almost entirely linked to the success of the play of Love on the Dole:

As for Wendy Hiller, to return to the lesser known, who plays the daughter and saviour of the family, whether her superb performance is due to a miracle of casting, or whether we have here a ready-made actress of absolutely first-class quality, time alone will show.

Authenticity in both the story and the performance was a prime reason for positive critical approval of the theatrical adaptation of Love on the Dole, and this partly stems as here from a sense (only partially true) that the actors themselves came from Lancashire and perhaps working-class backgrounds (for further information on the cast see: Three Cheers for the First Night, 26 February 1934! Audrey Cameron’s Celebration Copy of Love on the Dole * ; Wendy Hiller and Love on the Dole * and One of Our Portraits is Missing: ‘Drusilla Wills as Mrs Jike in Love on the Dole’ by James Arden Grant (1938) * ).

Vernon Woodhouse (1874-1936) was a veteran reviewer and playwright who died aged sixty-two, only a year and a half after writing this lively review. His obituary records that he died after a long illness and that he had been the drama critic for several periodicals including the Passing Show, Sporting Life and The People. He had only started writing plays (usually with a co-writer) in the early nineteen-twenties, including the rather successful The Limpet, written with Victor MacClure, produced in 1922 (The Stage, 18 June 1936, p.13). Woodhouse himself said The Limpet was a ‘farcical comedy’ (the Daily Herald, 8 August, 1922, p.5).

Rouson’s ‘sketches’ run parallel to Woodhouse’s review rather than directly correspond to it (which seems likely to be the general case with illustrated reviews). Firstly the illustrator, who has to work strictly within the page-space available, has the task of selecting which characters or scenes from the play to highlight in the published review (it seems more than possible that during a performance an artist such as Rouson might make considerably more ‘sketches’ than he was finally able to use). In this case the illustrator has chosen seven characters, five (or perhaps six) in joint scenes, who are all referred to by Woodhouse, leaving only one without a graphic response (Harry Hardcastle, played by Alex Grandison). The illustrations include Mr and Mrs Hardcastle, Sally and Larry, and the ‘chorus’ of older women: Mrs Dorbell, Mrs Jike, and Mrs Bull. Mrs Hardcastle appears separately from her husband at the top right of the page. She is shown in what is clearly felt to be for her the routine domestic labour of ironing (though actually in the play we only see Sally ironing in the opening scene, as required by the very first stage direction).

The caption makes clear Rouson’s verbal reading of Mrs Hardcastle’s role in the play, and indeed Sally’s reference at the end of the play to not wanting to end up like her mother supports this idea. However, I am not sure the drawing is quite in tune – it is a good likeness of Cathleen Nesbitt, but she looks in quite good form for someone who has spent years of relentless domestic labour on an inadequate diet and income (but perhaps that is true too of Cathleen Nesbitt in the role – maybe not the ideal casting decision, though her performance was often praised). Mary Merrell (1890-1973) in the film adaptation of Love on the Dole is certainly made up as an older, greyer and more anxious figure. Rouson’s caricature effects here include an exaggeration of Nesbitt’s nose and chin, a common feature of caricature.

Below Mrs Hardcastle, Rouson places Sally Hardcastle and Larry Meath in the one scene of the play (Act II Scene 2) set outside the industrial gloom of Hanky Park, when they go for a Sunday ramble on the moors. The caption introduction stresses this by substituting for the play title Love on the Dole the contrasting ‘Love among the Mountains’:

The couple certainly greatly enjoy the escape from Hanky Park, and from the industrial urban pollution to the clean air and wide panoramas of the moors (the circular frame reflects the spotlighting of this scene in the Garrick production, referred to below in the Tatler review in two of its few disapproving phrases as ‘an aureole of saccharine sunlight’ and ‘that tuppence-coloured circle of sunlight on the moors’). Rouson seems to draw the moors as having positively alpine peaks in the space behind the two. His sketch of Sally with blond hair is unusual – Wendy Hiller always played the part as a brunette (and I think wore a dark-coloured wig for this scene in which her hair was wind-swept). I think this alteration of hair colour is part of his rather sexualised illustration of the scene, where Larry’s eager expression and Sally’s closed eyes and raised bare leg suggest a sexual excitement which is not so obviously there in the play as written. In the play-text both clearly feel liberated by their shared natural surroundings and temporary escape from Hanky Park, but their conversation is quite cerebral. Sally feels there is something rare in this ‘special place’ and asks Larry if he believes in God, a question he rather side-steps by saying he certainly can’t believe in God when he is in Hanky Park. They then talk about whether Hanky Park could ever be escaped. It IS is several senses a romantic scene, but Rouson swings it in his drawing to something more openly sexual than it is (after all Larry and Sally are contrasted in novel and play with the younger Harry and Helen who do give in to their passions and end up ‘in trouble’ – homeless and out of work juvenile parents). That is not to say that reviewers – and especially press photographers – were not also sometimes over-excited about Sally’s appearance in hiking shorts, as the cigarette card production photograph of Wendy Hiller may suggest in its own (more subdued) way:

Nevertheless, this response by Rouson seems to me slightly out of kilter with the seriousness of the scene in the play.

Below the drawing of Sally and Larry is one of the ‘chorus’ of older women at a table, which is a representation of their visit to Mrs Hardcastle in Act III, Scene 2, after Larry’s death and Sally’s terrible bargain with Sam Grundy.

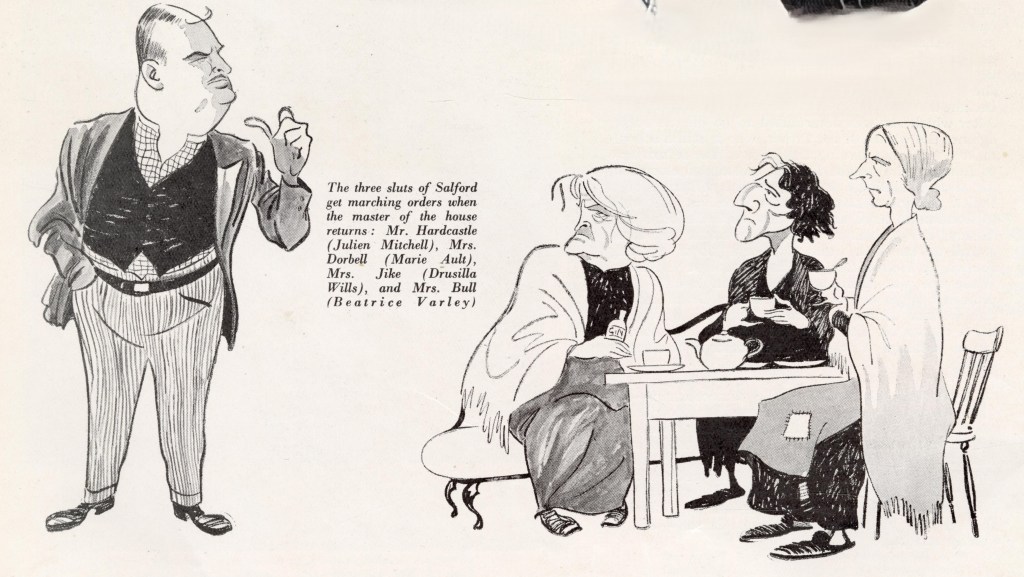

To the left is Mrs Dorbell, in the centre is Mrs Jike, and to the right is Mrs Bull. In each case Rouson exaggerates facial features in particular for each character/ actress – with special attention paid to noses and chins (and Mrs Dorbell given more than a hint of moustache). All three are shown wearing shawls, and it looks to me as if Mrs Bull at least is wearing her bedroom slippers. Mrs Dorbell is adding a nip of gin to each cup of tea (and no doubt charging for it). Mrs Hardcastle is very distressed by the news that Sally has agreed to Sam Grundy’s terms, but the ‘chorus’ are happy to make this ‘happy event’ an excuse for a celebration, though they are in someone else’s house. In the play-text is this stage direction and speech: ‘MRS JIKE (who has been drinking diligently). Come on, gels! Let’s be happy while we can. Y’re a long time dead’ (Cape edition, p. 118). Though this drawing looks as if it might be a self-contained scene of the three older women, it in fact interacts with another drawing to its left, showing Mr Hardcastle just returned home to find the trio well-established at the kitchen-table. All three women are turned towards this sudden interruption to their impromptu merry-making. As the caption makes clear, he immediately orders them to leave the house, which they do. In the play-text he simply says: ‘Get out o’ here!’ (p.118). The description ‘three sluts’ is more likely to refer to their ‘slatternliness’ rather than any alleged sexual behaviours, though they do each in their own way think that Sally has made a ‘good bargain’ with Grundy.

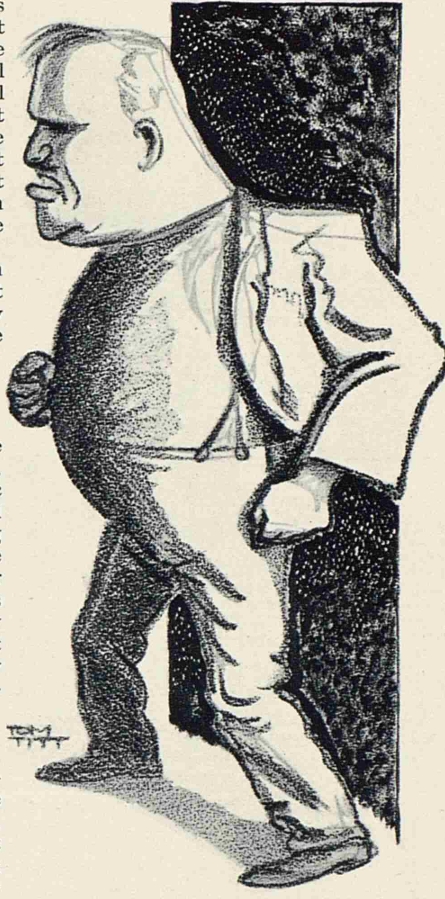

Here is Mr Hardcastle in Rouson’s view, making a gesture which makes very clear his attitude to these ‘guests’:

Rouson draws Mr Hardcastle wearing the clothes of a working-man of the time, which undoubtedly reflects his costuming in the production at the Garrick: suit trousers, straining belt, open-necked shirt with no collar, waistcoat and jacket. He also shows him as stout and balding. As with his drawings of other characters / actors, Rouson’s sketch is a good likeness but also exaggerates features – in this case Julian Mitchell’s thick neck and stomach (while his nose and chin are much less subject to caricature). Still, he is clearly shown as a man still retaining some authority despite his reduction by worklessness. Here is the whole scene with the three older women and Mrs Hardcastle:

That is Rouson’s final image in the Bystander illustrated review. As well as giving a good sense of character (partly through good portrait-drawing, partly through the exaggerations of caricature), there is also considerable dynamism in each image, giving a sense of the interactions between characters and thus of the drama of particular key scenes in the play. The only image which is more about character than about drama is the first one of Mrs Hardcastle, implying that for Rouson she is a relatively unchanging part of the household, wholly defined by her role as mother and housewife (a very plausible reading of the play’s depiction of her).

Rouson seems to have been active as a newspaper cartoonist from around 1932 until 1969. He was born in 1908 and died in the US in 2000. His full name was John Henry Rouson, and his work was at points syndicated to some 300 papers, including French newspapers as well Anglophone ones. (3) He had a number of regular cartoon series over several decades including ‘Shop Acts’, ‘Boy and Girl’, ‘Little Sports’ and one remarkable one devoted to Gracie Fields called (of course) ‘Our Gracie’. These are in most respects quite typical cartoons of a certain sort – usually with four panels and text in each leading to a comic punchline. They are not in any way political or current affairs cartoons. These cartoons are drawn in a style completely different and much less complex than his Bystander sketches, which were a regular feature of its theatre reviews (and sometimes other features about celebrities) from 1932 until 1940. This end-date was no doubt because Rouson, who had experience as a yachtsman, had joined the Royal Navy as an Ordinary Seaman. After participating in the Dunkirk evacuation, he volunteered to work in RN bomb and mine disposal and after five years service in this dangerous trade ended the war as a Lieutenant Commander with an OBE and the George Medal. He was posted to the US in 1944 to lecture to US Navy personnel on ordinance disposal, and after studying painting in France for two post-war years, he emigrated to the US in 1948 to continue his work in cartooning. He soon had a contract with the New York Herald Tribune as a ‘theatre caricaturist’. (4)

The Punch review was also a thorough one, signed by ‘H.F.E’. It opens with a concise and useful plot summary, emphasising that the three main male characters each in turn lose their jobs and that the Hardcastle family have to live in ‘circumstances of ever increasing poverty’. The reviewer feels that it is these circumstances, characters and plot events which form the ‘bare bones of the play’ and give it its ‘immense effect’. He also argues that this power to move is increased by the lack of explicit political persuasion, though he does not discount implicit political impact:

There is no screaming here against capitalists or politicians, no attempt to force a contrast between the lives of these forsaken people and the lives of the well-to-do (that would be superfluous when one only has to look from the stage to the stalls to see it), only a plain straightforward statement of fact.

It is notable that the reviewer sees a clear separation between the class of the audience and the class of the play characters in the Garrick performances – but of course both in pre-London and post-London touring performances we know that there were much more varied audiences, certainly including working-people (if not so much workless people) and venues such as variety theatres. H.F.E articulates in plain but powerful words how he thinks an average audience is likely to respond to the play:

This is how these people have to live. You can see their courage. You can see how they fight to keep their ideals and their self-respect. And you can see too how, unless they can get work instead of just the dole, sooner or later they are bound to go under. Life is too unfair for them.

The review then moves on to ‘the moral problem of Sally’s final bitter determination to get something out of life for herself and her family’, but sees this as not the crux of the play but rather a consequence of the ‘bitter injustice of a world which could force even the thought of such a way out on a girl of Sally’s innocence and courage’. Rather, H. F. E. argues, it is Sally and Larry’s relationship which is at the centre of the play:

Both of them hate Hanky Park and all its works, both are determined not to let its demoralising influence kill their love of decency and beauty. But Sally feels, once she is sure of his love, that with a home of her own, however poor, and him, she could forget it and be happy. Larry knows that he could not. He could never be content to shut his eyes to all the misery and squalor around him. He wants to do something about it. From the very start, before Larry loses his job, Hanky Park is a bar between them, threatening their happiness; and in the end it kills him.

This is an acute analysis of some of the discussions between the two while up on the moors that Sunday, though its reads Sally rather stereotypically as a woman focused on romance and the individual, and Larry equally stereotypically as a man more focused on the political and collective. The play-text (but perhaps not the performance?) suggests something a little more fluid: that during the scene Larry does believes that it is very hard to escape the systematic oppression of Hanky Park, but also that he is at least attracted to a shift to a more individualistic romantic happiness. Of course, he, unlike Sally, knows from the beginning of their outing that he has lost his job at Marlowe’s, that he has not escaped the system, and that individual happiness cannot thrive without adequate economic underpinnings. A further six years on, the film-script considerably rewrote this scene and has Sally saying that she does not want Larry to give up his collective political ambitions, and that she would like to know more about how people like them live in general, and why they cannot have decent places to live.

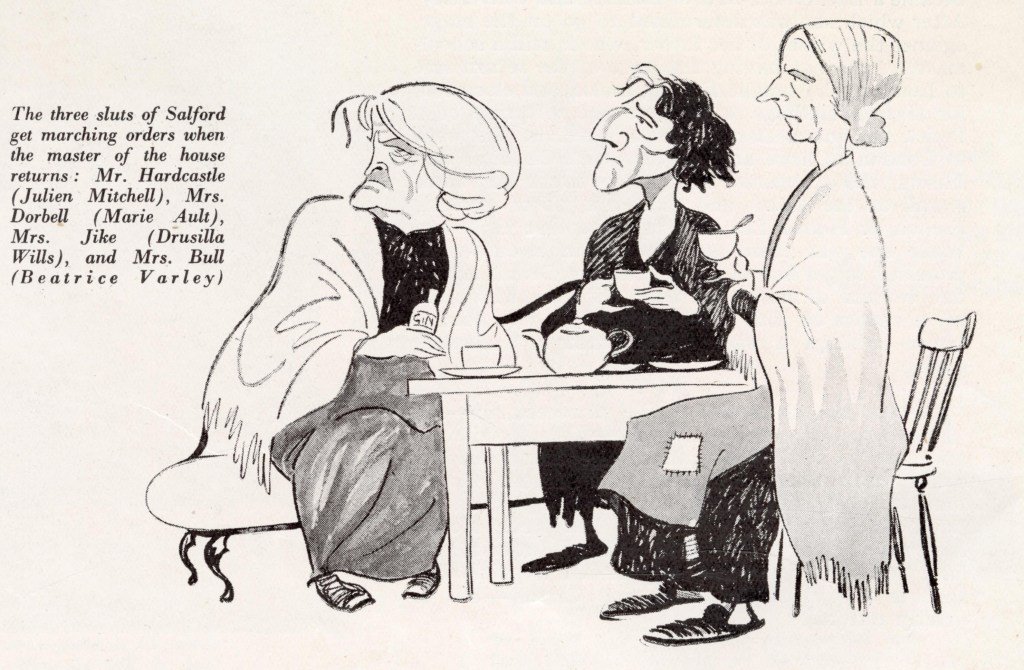

H.F.E. next moves logically from Sally and Larry to the actors who portray them. He sees Wendy Hiller as an emerging star, with her performance of Sally a’ personal triumph’, based on her ‘naturalness, her sincerity and charm’. However, he also notes the essential ensemble nature of the play and praises the whole cast: ‘The general level of the acting among a cast fourteen strong is extraordinarily high’. Julien Mitchell (Mr Hardcastle), Cathleen Nesbitt (Mrs Hardcastle), Ballard Berkeley (Larry Meath) and Alex Grandison (Harry Hardcastle) are ‘all excellent’, as are ‘the Three Witches’: Marie Ault, Beatrice Varley and Drusilla Wills (Mrs Dorbell, Mrs Jike and Mrs Bull). Of these characters H.F.E. observes that:

Their visits to the Hardcastle kitchen always terminate in the same way, a violent command to get out; but, like Nature, they always come back . . . to pour out their evil counsel on the silent Mrs Hardcastle’s head and to add a little humour to lighten (though not disperse) the tragic atmosphere. A scurrilous but welcome crew.

This gives a very good sense of the complex and layered tragi-comic impact of the trio of older women. ‘Altogether’ sums up H.F.E. ‘a strong, well-written, well-acted and very moving play’.

Given this review, which is full of insights and covers thoroughly the major concerns, plot, setting, characters and acting of the play, the Punch illustrations seem rather selective (compared to those of both the Bystander and Tatler illustrated reviews). There are two drawings, and of the characters named as central by the written review they include just the ‘chorus’ of three, and one focussing on an individual, a policeman, together with a background scene. Unlike those in the Bystander, which have a similar scale to each other, these are drawn to quite different scales, with a more distant and closer viewing distance respectively. Here is the first illustration, of the constable and the archway with a view onto the railway line:

I do not think this is obviously caricature because there is no exaggeration of the policeman’s features – indeed because he faces away from the reader/viewer, his face, the prime target of caricature, is simply not visible. His arms are perhaps somewhat overly-long for a realistic image, but nevertheless I would see the image as closer to illustration than caricature, though the self-contained caption is more like that of a cartoon than any we have so far seen. In addition to the solid black rear silhouette of the constable there is also a view of his setting in Hanky Park, something we did not see in any of the Bystander drawings (though Larry and Sally get a hint of background from the mountain peaks). The sketched diagonal, cross-hatched and vertical lines, and their disruption by the flood of light/white paper shining from the lamp, give a good illusion of Hanky Park at night, when the constable is on his beat. That background scene is quite closely based on the original set in Act II scene 1, which featured a railway archway with a view onto the railway-line. This scene and the policeman clearly caught Stampa’s interest, but unlike all the characters we have so far seen drawn it seems an odd selection, for the policeman has a minimal though not wholly insignificant part in the play. In the London production, as recorded in the Samuel French edition of the play, he has no lines whatsoever, but is only a physical representation of Law (which does not prevent Harry and Helen trying to avoid being seen by him, as if they are transgressing merely by meeting each other in a back alley). In the Cape edition of the play which records the Manchester performance, the policeman has some sixteen lines – mainly in dialogue with those shady characters Sam Grundy and his side-kick Charlie. However, in none of his speeches does the policeman say ‘Ba Goom! That’s t’ second oop train in five minutes’ (unless this was an improvisation not captured in the two printed versions of the play). This pointless observation is a pure invention on (I take it) Stampa’s part and makes the policeman into a comic working-class character, when in fact he is a more serious figure in the play, either as a silent expression of authority in night-time Hanky Park or as an ambiguous keeper of law and order who is perfectly familiar and comfortable with Sam Grundy and his illegal street betting business (perhaps because of silently implied quid pro quos). Curiously, while it seems to me that the drawings are not caricatures, this alleged line surely IS a caricature. Having said that, some reviews did single out Edmond W. Waddy for his cameo performance as the constable.

Stampa’s second drawing is of the ‘chorus’ of older women, whom we have already seen illustrated (and illuminated) in the Bystander review:

I would see this as belonging more to the tradition of book-illustration than to caricature. The three older women may not exactly be drawn in a style of high realism, but neither are their facial features subject to the kind of exaggeration seen in Rouson’s sketch in the Bystander. This image does not seem to capture the three in a particular scene in the play but to imagine them in a posture of habitual gossiping – from their facial expressions very intent on and intrigued by what news they have to exchange as they stand in a tight group. The caption of ‘The Three Witches’ gives the image a significant inflection, associating them with the three witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Greenwood knew his Shakespeare very well, but at no point in novel, play or film did he call these characters witches (nor for that matter, a ‘chorus’). Nevertheless, from very early in the run of the Garrick production reviews began to apply this label of ‘witches’. The earliest review I have found making this link is in a brief Daily Express notice of the play which notes that:

Love on the Dole reached the West End last night. It has the same sort of ‘entertainment value’ as [ Sean O’Casey’s] Juno and the Paycock – vivid, mean, street-character-studies (especially by Drusilla Wills, Marie Ault, and Beatrice Varley, as three harridans far weirder than the Macbeth witches) (31 January 1935, p.11).

However, and despite the bold statement of their identities in the caption, I don’t think the drawings themselves do suggest that the three women are ‘witch-like’. It is, of course, a term loaded with centuries of prejudice against older women and here draws both on Shakespeare’s depiction of the weird sisters with their supernatural powers, and on OED‘s sense I.3.a: ‘derogatory. As a term of abuse or contempt for a woman, esp. one regarded as old, malevolent or unattractive’. However, Stampa’s avoidance of caricature in the way of lengthening noses and chins rather takes the illustrations away from the ‘witchlike’ and (at least) towards a more realist portrayal of three older Salford women gossiping, an activity through which they exchange useful intelligence for economic use in their various (not necessarily wholly honest) small-business activities and also construct their social lives. The drawings are indeed also recognisable portraits of the three actresses in these roles, as you can see by comparing the image with the exaggerations of the previous (and following) caricatures.

Like Rouson, G.L. Stampa (1875-1951) had a distinctly individual career. His full name was George Loraine Stampa, and he was born in Istanbul, where his father (who was of Italian heritage) was architect to Sultan Abdul Hamid. The family moved to Britain after the Sultan faced an uprising in 1878. G.L. studied art first at Heatherley’s Art School and then at the Royal Academy Schools. He exhibited at the Royal Academy, but he became associated with Punch very early in his career, aged nineteen, when in 1894 the editor asked him to contribute an illustration. He then contributed to Punch regularly for the next fifty-three years, publishing his last drawing in 1949. He did many illustrations for theatre reviews for the periodical, and also drew for both the Bystander and the Tatler, as well as for mainly humorous books (see his Wikipedia entry https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Loraine_Stampa).

Finally, we come to the substantial Tatler illustrated review of Love on the Dole, with its five drawings, three of which are of ensembles. The review is by Alan Bott (1893-1952), a drama critic for several London newspapers and periodicals, and is headed with the rather fine summary, ‘Lancashire’s Lost Souls’ (though also with what seems a less suitable and perhaps politically-neutralising heading, ‘Entertainment a la Carte’, presumably suggesting that the audience may take what they choose from this tragi-comic narrative). The review is, like our first two reviews, very positive about the play overall, though it is less convinced by the character of Larry Meath. Alan Bott begins with an overview of the play’s emotional and persuasive power, thinking it more effective than the original novel in being less explicitly political:

if Love on the Dole had been written in bitterness, or as a tract for the times, it would have had a lesser effect on the heart and the mind. Its story indeed is more impressive in the new play . . . than it was in Mr Greenwood’s novel; for the play contains little of the novel’s zealous ecstasy and none of its oblique propaganda. At the Garrick Theatre they are mostly real people, with needs and circumstances that are the more poignant for not being used as a case for social argument.

Quite a range of newspapers took a similar view that a greater social/political impact was made by the play through avoiding overt political commentary. The review then moves to its main reservation about the play which concerns the role of Larry, essentially again focusing on the relationship between drama and politics:

Larry, like other idealists in the modern theatre, is more plausible in politics than in personality. He desperately wants to make this world a better place for Hanky Park, poisoned by smoke, poverty, pawnshops and its dreams of a luxury obtainable though street-betting and Irish sweeps. He is indicated as a practical visionary, but the fervour becomes dim frenzy in his human relationships.

I do not entirely agree with this, for Larry is tempted, as he says in the scene on the moor, to give up his politics for love of Sally, but knows that such individualism would be fruitless. However, it is true that compared to the novel (and the then future film) Larry’s role is considerably reduced in the play so that Sally becomes the more central figure, which the review notes in pursuing its argument that Larry is unconvincing in his personal dimension:

His mind rings clear, his emotions do not. As a result, his scenes with Sally Hardcastle . . . are the least moving parts of Love on the Dole. [When Larry tells Sally that he has lost his job] the tension and sadness should vibrate through the theatre . . . [but] examine the sympathy, and you’ll find it is all for the girl; the reason being that she is a person, while the man seems less an individual than a type.

I think there may be a certain underpinning belief here (with which I do not concur) that the political is inherently NOT the personal, and hence not a fit subject for explicit treatment in a dramatic narrative. Nevertheless, this is nicely-argued and an acute review in its own way.

Fortunately, having dealt with Larry, the rest of the review regards the play highly:

That, though, is the only faint portrait in the author’s gallery of Lancashire people. Each inhabitant of the Hardcastles’ house contributes fine detail to the play’s heart-breaking detail. The father, workless for two years, is animated by a resentment which he cannot focus. He is angry with someone, but the devil of it is that he doesn’t know whom.

The reviewer also notes shrewdly that when Harry reports that he will have to marry in a hurry because Helen is ‘in trouble’, his father shows that ‘respectability’ is one of the very few things he has left: ‘the Paterfamilias . . . whose respectability is proof against destitution’ turns him out of the house. The authenticity of each of the character’s situation is praised, as are the performances of all of the cast. Then the review sums up the overall effect of the play, dealing with some issues also raised in the Bystander review, including the potential difficulty of the piece for some audience members, and the avoidance of explicit political debate in ways which will nevertheless raise political questions for its viewers:

It is, for some few, an uncomfortable play; but it can be appreciated by all who want from the theatre something more than a comfortable escape from reality. Its great merit, apart from its well-rounded characters, is that it tells a tragic story in a straightforward manner and convincing sequence, and leaves the audience to search for cause and effect. Its grimness is relieved by homespun humour. It never preaches; and only incidentally does it inspire more sympathy for the victims of economic chance than can come from half-a dozen sermons.

This is in line with Bott’s earlier views that the explicitly political does not work in the theatre, but nevertheless it sees the likely audience response to the narrative as leading to political questioning, and sees its impact as more powerful than sermons about the poor and unemployed (though for a sense of just how many sermons were preached on the text of Love on the Dole see Love on the Dole and the Clergy *). Finally Bott praises the acting: ‘the acting in four of the leading parts is flawless’ – but then goes on to praise by name ten of the actors in the ensemble of fourteen.

Captain Alan John Bott (Military Cross and Bar) was a theatre critic with the slightly unusual distinction of having been a World War One fighter ace in the Royal Flying Corps between 1916 and the end of the war, an experience about which he published two books. While serving in the Middle East in 1918, he was captured by Turkish troops after a forced landing, but escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp near Istanbul and made it as far as Salonika in Greece in time for the Armistice in November. Before the war he had been a journalist working for the Daily Chronicle, and after the war returned to journalism, but with a new emphasis on theatre reviewing. He also in 1944 founded Pan Books (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Bott).

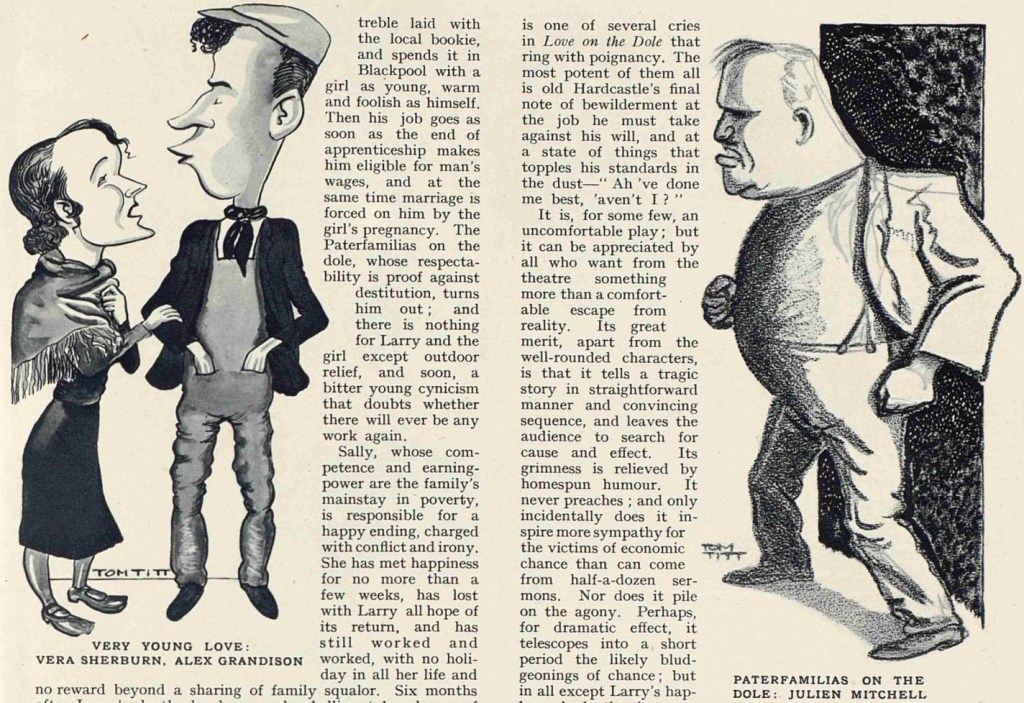

We can now turn to the rich images accompanying this review. The first striking drawing, which I used to introduce the whole article, is of Larry Meath, as played by Ballard Berkeley:

This is the second drawing of Larry across the three illustrated reviews, and it certainly presents him in a heroic mode (where in the Rouson drawing he looks a more straight-forward romantic lead) despite some elements of caricature. Ballard Berkeley had pretty regular features, as suited a romantic lead, so there are no obvious features to exaggerate, but his jaw is rendered more than realistically firm and jutting, befitting the heroic effect of the drawing, rather than making it too much of a caricature. In general style, this is suitably in the vein of a contemporary social realist or even socialist realist portrait of a heroic worker (modes of representation which in the first case represented serious social issues and in the second showed the active participation of the proletariat in the class struggle). (5) One might consider it a parody of that mode, but it seems to me to give Larry Meath considerable dignity as a labour leader. Note the figure’s relationship to the industrial landscape of Hanky Park: he is, of course in the foreground, but nevertheless the proportions of foreground and background make him look like a giant, an epic figure who towers above the works buildings and chimneys, and has his head (full of dreams and aspirations) in the industrial smoke-becoming-cloud which always shrouds Hanky Park. The smoke-clouds interestingly prefigure the background to the credits in the 1941 film of Love on the Dole, where they presage both hope and danger, though presumably because both adaptations have read the novel attentively (the smoke was distantly hinted at the in the stage set for Act II, Scene 1, as reproduced in a photograph in the Samuel French edition of the play, facing p.31). Larry is naturally wearing the clothes of a working-man – collarless shirt, waist-coat, neckerchief – as he strides purposefully forward into the hoped-for better working-class future. The background buildings and chimneys are adaptations of the images of Hanky Park on the Garrick Theatre programme for the play, which in turn were adaptations of the dust-wrapper design of the first edition of the novel. I think this is a rather fine drawing and it is appropriate that it occupies a central and quite dominant position on a level with the text of the review. Its image of Larry may or may not match Alan Bott’s response to him: perhaps it does in showing his political identity as primary, or perhaps it doesn’t in showing Larry as nevertheless a strong character in the drama.

At the head of the page is an image taking in six characters shown against the railway arch which formed the set backdrop for Act II, Scene 1.

Though more highly-populated, it is thus a variation on the Punch drawing of the arch and the policeman in that scene. In the centre we have the policeman played by Esmond W. Waddy looking out at the passing train, with its lighted carriages and its contribution of further smoke to the smog of Hanky Park. He has no individual comic lines, though: all of the five/six characters in the image are covered by the caption ‘At odds with life in ‘Anky Park’, a clear and appropriate equivalent to Bott’s ‘Lancashire’s lost souls’ (though one might query its application to the policeman and even more so to the bookie Sam Grundy). To the left is a drawing of Grundy (played by Arthur Chesney) trying to persuade Sally (Wendy Hiller, of course) that he could ‘help her’ and would just like to be her ‘pal’, and why not have a few of the pound notes he has in his pocket. Sally says she doesn’t even want to talk to him, and that she should spend more time with his wife rather than ‘pestering girls as wouldn’t wipe their feet on y’ (Cape edition, p.69). This dialogue, plus the actual height difference between the two actors, may explain the drawing in which Sally looks disdainful (even patrician?) and by far the more powerful of the two (however, one might also note the complacency of the expression on Grundy’s face – he is more than confident enough in his own power to take a put-down or two from Sally in the conviction of final ‘victory’). It is a very different image of Sally/ Wendy Hiller compared to Rouson’s sketch.

To the right of this image, just exiting down an alley by the railway arch, are Mrs and Mr Doyle (played by Dorothy Dewhurst and Harry Mann), who are not characters with major parts in the play. In fact, they are not even in the Cape edition of the play (which was based on the Manchester Repertory production), though they are in the Samuel French acting edition which is based on the Garrick Theatre production in London. As the critic Ben Harker notes, these two characters were introduced into the London production partly to give two understudies actual stage appearances and partly to cover the audience settling down after the interval. (6). Nevertheless, the review’s illustrator was clearly struck by the pair in the performance: Mrs Doyle finds her husband drunk in the street, queries where he gets the money from when his family needs food, and dares him to hit her, before adopting a more conciliatory tone and pleading illness on her husband’s part, as the policeman comes into view. Clearly she regards her family problems as private, whatever her husband’s failings, and does not invite the intervention of the law (see the Samuel French edition pp. 31-2). There is a sixth character to the right of the Doyle’s, but though he is clearly a working-man, he is not assigned an actor in the caption and I simply do not know who he is! He could be Grundy’s sidekick Charlie, who appears in this scene, but not does look crooked enough or well-dressed enough for the part. Perhaps he is a representative street-corner bloke – that being one of the few, though utterly boring and uncomfortable, places where workless men could spend time without spending any money.

The second page of the Tatler review has three images, two at the top of the page and one at the bottom of the page. At the top-left is a drawing of Helen Hardcastle and Harry Hardcastle.

Both wear the clothes of working-people – Helen a plain dress and a shawl (though not clogs), Harry a cap and neckerchief, but no shirt, not even collarless, because he has to make do with his work overalls, lacking at this stage of the story any other clothes whatsoever (as a stage direction notes ‘He is a slightly-built boy of seventeen. he wears blue overall trousers and a jacket which is much too small for him’, Act I, Cape edition, p.23). Both characters have elements of caricature in their faces – Helen/Vera Sherburn has her nose and chin sharpened, while Harry has a rather strongly emphasised nose and mouth. I am not certain which scene of the play this refers to but it could be when the two very awkwardly agree that they like each other (Act II, Scene 1, Cape edition, pp.56-7) – though I find Harry’s expression rather difficult to read in the drawing. This scene would accord well with the caption’s succinct comment: ‘Very Young Love’. I think we might also read this naive declaration of love in relation to the image of Mr Hardcastle, though it is separated by a column of review-text. He is clearly portrayed in a moment of great anger, and though there are several points in the play where his situation and feeling of hopelessness, as well as the behaviours of his children, drive him to uncontrollable fury, one of these arises from Harry’s confession that he and Helen need to get married quickly.

Equally, though, it could be that this image sums up Mr Hardcastle’s cumulative experience of anger as things fall apart. We see him angry at Harry’s need for a suit, at Harry’s asking that he and Helen share Sally’s room when they have nowhere else to go, and at the news that Sally has made her terrible bargain with Sam Grundy to save the family from destitution. It is a striking drawing which differs in style from all of the other Tom Titt illustrations in this review, for it is notably more sketch-like, less finished, and yet powerfully shows Mrs Hardcastle’s whole body contorted by fury, his lips parted, his teeth bared, his belly thrust forward, his fists clenched, his legs apart and tensed for action. While the general features resemble those in the Bystander drawing of him (the belly, the bulky body, the bull-neck), there he is still in control of himself, retaining his dignity; here he has lost all control, become almost animal in his expression of frustration through aggression:

I am, however, puzzled by the dark, textured, rectangular space behind him: is it a further symbolic representation of his anger or an image of the seams in the coal-mine where once he could use his strength productively to keep his family?

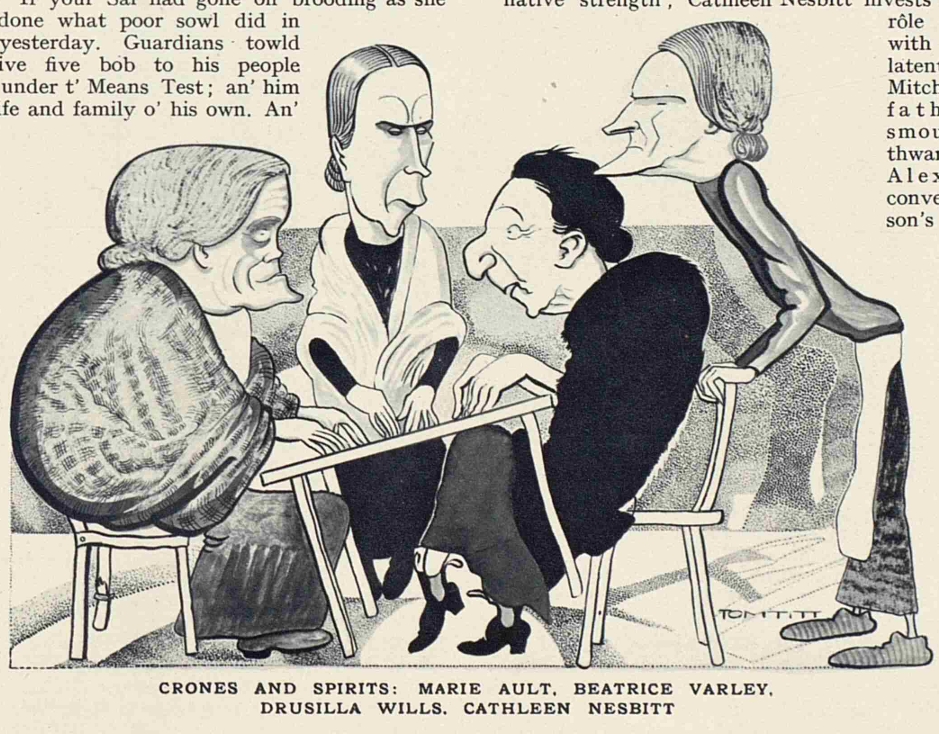

Finally in this review comes the drawing of the ‘Chorus’ and of Mrs Hardcastle. Despite the presence of the table, this is a different scene in the play from the one shown in the Bystander cartoon. While that scene was from towards the end of the play, when Mr Hardcastle orders the three women out of the Hardcastle house, as Sally departs, this is from nearer the beginning of the story, when the three older women hold a séance to which Mrs Hardcastle is also invited (Act I, Cape edition pp.44-49). The trickery of Mrs Jikes is clearly exposed in this drawing which shows her knee moving the table to suggest the responsiveness of the spirits. All four characters show the exaggerated features of caricature, with Mrs Hardcastle / Cathleen Nesbitt having an even sharper chin and nose than in the Bystander caricature. Here the older women are called ‘crones’ rather than ‘witches’, though the two terms share a number of resonances. The caption indeed links them to the supernatural/ fake supernatural with its title of ‘crones and spirits’.

Tom Titt was the pen name of the Polish-born artist Jan Junosza de Rosciszewski (1885-1956), who came to London to study art at the Regent Street Polytechnic in 1907. He published his first cartoon in the the New Age magazine in 1911, and in the next few years he drew cartoons for many illustrated newspapers and periodicals. He became the theatrical caricaturist for the Tatler in 1928 and continued that work until at least 1948. (7) In August 1948 (p.7) the Tatler published a photograph of the cartoonist with a caption to mark his twenty years as their theatre caricaturist. The caption explains that he took his pen-name from the English name of a bird which he first saw used in a 1910 documentary about birds: Bird Life. The correct title is Glimpses of Bird Life (directed by Oliver G. Pike, production company Charles Pathé (IMDB https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3674136/fullcredits/?ref_=tt_ov_ql_1). The BFI Screenonline website comments that this was ‘a pioneering film of birds in their natural habitat’ and that it was widely distributed, including in Britain, France and Germany (http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/1271010/index.html ). Tom Titt published a substantial column titled ‘British Films in Poland’ in the Era in August 1919 (p. 17), suggesting both his own interest in cinema and that British films were screened in his native country from early on, which was presumably how he came to see the 1910 bird film.

Many aspects of Love on the Dole‘s reception as novel, play and film are unique in showing its wide-reach and its impact on public perceptions of poverty and unemployment. These cartoon contributions to the play’s reception and interpretation are not unique in quite the same way, in that the Bystander, Punch and Tatler produced similar verbal-pictorial hybrid responses to many new plays over a considerable period between the wars and for a while afterwards – though this engaging and creative reviewing practice has been largely forgotten. However, nearly all the other illustrated reviews were about plays featuring upper-class or middle-class life, because there was so little drama about working-class characters and lives, so what is exceptional are these written and drawn responses to a play wholly focused on the catastrophe of the Depression in the so-called ‘Distressed Areas’ of Britain. This seems to have brought out quite distinctive work on the parts of these three artists, Rouson, G.L. Stampa and perhaps especially Tom Titt, whose portrayals of Larry Meath and Mr Hardcastle seem striking and full of insights into their parts within the play.

The illustrated reviews also contribute to what we now might call the multi-media impact of Greenwood (and Gow’s) Love on the Dole. In the thirties and forties there must have been many people who had read the novel, seen the play and the film, and also read the reviews and looked at the cartoons with their representations both of key characters and of their environment: the grim streets, houses and works of Hanky Park, which were nevertheless where they had to make their homes.

There were indeed further cartoon responses to the play of Love on the Dole, though mainly through single cartoons rather than these more extensive treatments we have traced. For example, there is this US cartoon from the New York Herald Tribune by ‘Selz’ responding to the Broadway production. It too shows Mr Hardcastle in an agressive temper, focused this time on his daughter Sally, in the key scene near the end of the play where he reprimands violently her for bringing shame on the family and she queries whether the near-destitute family can now afford ‘respectability’ without her unwilling self-sacrifice. Though this is not what happens in the actual staging, the artist here imagines what is often true in the play – that little is private, as two of the ‘chorus’ of older women listen in through the window.

NOTES

Note 1. As in the review in the Daily Express of George Bernard Shaw’s The Philanderer, where the reviewer writes ‘Following our visit to Blanco Posnet, I took Tom Titt to see . . . another Bernard Shaw play’ (21 October 1926, p. 4).

Note 2. For a substantial introduction to the history of the Baedeker travel guides see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baedeker .

Note 3. Information found on the Lambiek ‘Comiclopedia’ website: https://www.lambiek.net/artists/r/rouson_john-henry.htm and in an invaluable comic-strip history web-site which gives a full profile of Rouson based on an interview with him by Don Maley published in Publisher & Editor, 14 June 1969. See the very informative https://strippersguide.blogspot.com/2022/02/news-of-yore-1969-john-henry-rouson.html

Note 4. A search for ‘Rouson’ in the British Library Newspaper Archive gives hundreds of results (all for cartoons) across this period and in about half a dozen different newspapers.

Note 5. Wikipedia has articles on Social Realism and Socialist Realism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_realism. The Social Realism article concentrates unnecessarily narrowly on US examples, while the Socialist Realism article defines the mode exclusively in Soviet examples – it was interpreted more flexibly by leftists internationally.

Note 6. See his excellent article available online: ‘Adapting to the Conjuncture – Walter Greenwood, History and Love on the Dole‘ in Keywords – a Journal of Cultural Materialism, Vol.10, October 2012, pp. 55-72, page 63 and endnote 45: https://raymondwilliams.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/key-words-7.pdf .

Note 7. Invaluable information to be found in the accompanying notes to a 1930 Tatler caricature of members of the Doyle Carte opera company by Titt held in the collection of the V & A, London. See https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1657544/doyly-carte-opera-company-staff-drawing-titt-tom/. There is also an article by Dr J. Matthew Huculak about Titt’s cartoons of modern London streets, published in the New Age in 1913 and early 1914. See https://newage.omeka.net/exhibits/show/newage/titt. There is also a blog reproducing a fairly full record of Titt’s manuscript/drawing archive, sold on Abe Books in September 2018. See https://attemptedbloggery.blogspot.com/2018/09/tom-titt-manuscript-archive.html.