Preface

This is a substantial piece, long enough to cover the portrayal of small shopkeepers and shops in three of Greenwood’s major works, all of which offer different versions of the Hanky Park in which he grew up between 1903 and his success as a novelist in 1933 (there are small business people too in his 1934 novel, his Worship the Mayor and his 1938 novel The Secret Kingdom, but these are a tailor and a hairdresser respectively rather than shopkeepers exactly). Part 1 discusses the class and occupational structure of Hanky Park, according to Love on the Dole; Part 2 explores the relatively scant references to shopkeepers in that novel; Part 3 discusses the greater prominence of small shopkeepers in Greenwood’s 1937 short story collection The Cleft Stick; Part 4 covers Greenwood’s 1939 interview with a small shopkeeper in How the Other Man Lives and also looks at shops in his 1967 memoir There was a Time; Part 5 draws out some conclusions about why Hanky Park’s small shopkeepers matter and are worth this first-ever exploration.

The piece includes spoilers for the two main shop-keeping Cleft Stick stories, ‘The Little Gold Mine’ and ‘All’s Well That Ends Well’: some readers might want to read these stories for themselves first, which you can do in the digital facsimile edition of The Cleft Stick which can be downloaded from the Salford University Archives: https://salford.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma9913705718701611&context=L&vid=44SAL_INST:SAL_MAIN&lang=en&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine.

1. Introduction: the Shape of Society in Hanky Park

The society which the novel of Love on the Dole depicts seems to have a very flat profile in terms of class and indeed occupation. As the historian Stephen Constantine noted in his classic essay on the novel: ‘the story is set in a virtual single-class society’ (we will return to his observation right at the end of this whole piece). (1) Nearly all of its households and characters are firmly working-class, often lower-skilled, with many just making it while employed but never far from the poverty-line. Once the depression begins to bite and jobs begin to be cut, first by half-time working then by redundancy, practically all these households sink into poverty. This is at first somewhat cushioned by unemployment benefit (the ‘dole’) but then things get much worse under the austerity of catastrophic national economic belt-tightening by the National Government during 1931, with the reduction of benefit exacerbated by the Means Test, which in many cases removed all benefit payment from individuals if other family members in the household were considered to be earning a sufficient income, including through their own unemployment benefit.

Thus we have the central and in many ways typical Hardcastle family: Mr Hardcastle is a coal-miner, who manages while in work, Mrs Hardcastle does the demanding labour of running the household based on the combined (and then rapidly reducing) income of her family, Sally works at a cloth mill and Harry is an engineering apprentice. In principle, these occupations should more-or-less sustain the household in North Street, Hanky Park, Salford in reasonable economic times, but that the period between 1929 and 1935 is not. Harry’s fellow apprentices come from similar households and are similarly vulnerable. We also have a smaller number of characters working in Marlowe’s Works who have somewhat greater status and income, including Larry Meath, the qualified engineer, who has apparently achieved the security which the engineering apprentices hope for after their seven years training is up. There is also Ned Narky the crane driver at Marlowe’s, a brutal character who has been a sergeant-major in the First World War and who spends his war gratuity freely (until it is all gone) on drink and, up to a point, his abusive relationships with women. He is saved from poverty when Sam Grundy buys him off by corruptly getting him into the Two Cities constabulary, despite the fact that Ned has no interest in fairness, honesty or justice, though he does enjoy drinking and fighting with anyone, anywhere.

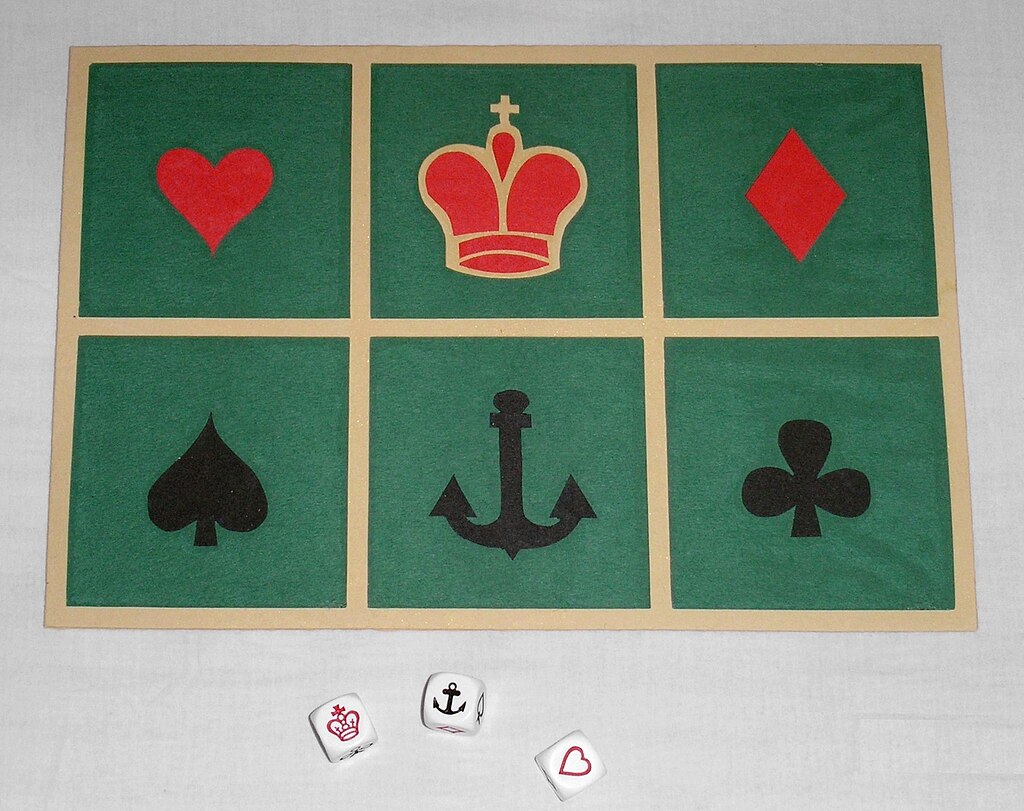

Then, much more exceptionally, there is the illegal on-street bookie, Sam Grundy, who offers the men working at Marlowe’s as well as the women of Hanky Park, the tantalising hope of a big win. He made enough money while in the wartime Army from running (as banker) Crown & Anchor games to set himself up in the betting business post-war at which he is making a great success, enough to be a car owner and to have a holiday house in Wales. (2)

On a much smaller scale of entrepreneurship is the quartet (reduced to a trio in the play) of older women who, from in several cases the relatively secure base of a very small old age or widow’s pension, ‘oblige’ their neighbours in one way or another. These are Mrs Nattle, Mrs Jike, Mrs Dorbell, and Mrs Bull – though the latter may be more of a helper as ‘handywoman’ or uncertificated midwife than the others who mainly have a sharp eye on profit from their little pieces of business, such taking items to pawn for a commission or acting as agents for clothing and burial clubs. That however is really the extent of the population of Hanky Park who appear as substantial characters. A few other relatively elite figures appear either in one cameo or only through scattered references. Sam Grundy makes some limited appearances, but the others in this local elite making up the ‘trinity’ of Hanky Park’s rich men are chiefly met through short references:

Sam Grundy, the gross street-corner bookmaker, Alderman Ezekiah Grumpole, the money-lender proprietor of the Good Samaritan Clothing Club. Price, the pawnbroker, each an institution that had grown up out of a people’s discontent. Sam Grundy promised sudden wealth as a prize, deeper poverty as a penalty; the other two, Grumpole and Price, represented temporary relief at the expense of further entanglement. A trinity, the outward visible sign of an inward spiritual discontent; safety valves through which the excess of impending change could escape, vitiate and dissipate itself (Love on the Dole, novel, p.24).

We get a little more on Price in one scene but almost nothing further on Grumpole, though his clothing club is vital for Hanky Park, it being the only way people can ever get any new clothes, though they are worn out before they are paid for. In addition, there are a few references to foremen, and managers at Marlowe’s Works, but almost no detail and in most cases not even individual names. (3)

2. Shops in Love on the Dole

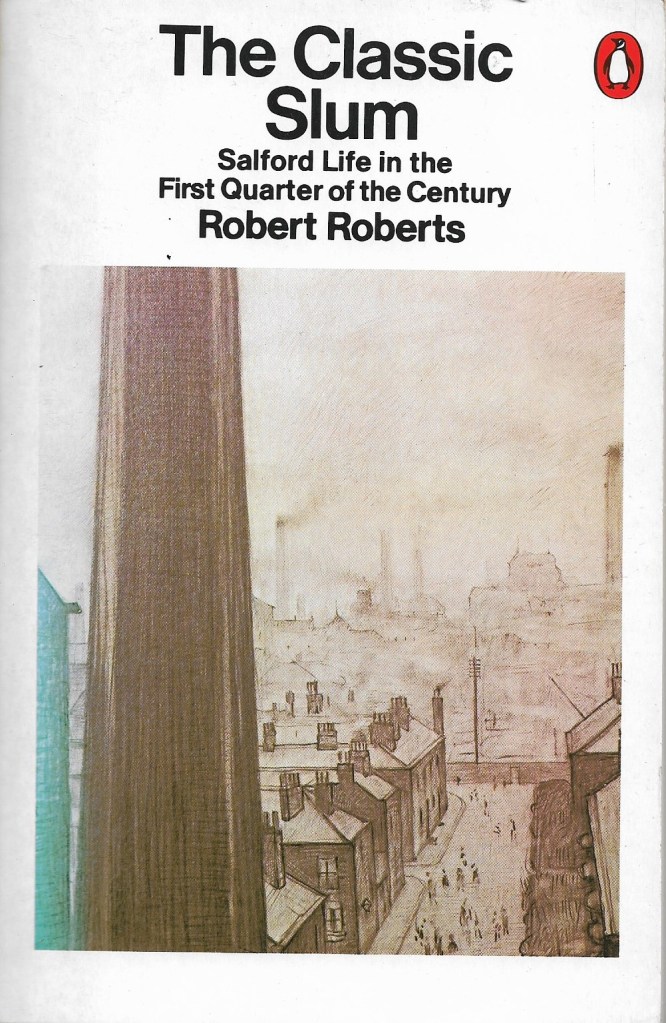

However, the people of Hanky Park must of necessity have had contact with some towards the top of their class or even slightly above or outside their own class. Robert Roberts, the author of the notable memoir / history The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century (University of Manchester Press, 1971) was brought up in a grocer’s shop run by his mother in a slum area (his skilled craftsman father had bought it from its previous owner with £40 of borrowed money while ‘tipsy’ – an unconsidered business decision which did not delight Robert Roberts’ mother, who nevertheless ran the shop for the next thirty-two years).

Roberts’ account is both scholarly and personal and provides rich contexts and parallels for Greenwood’s writing. Roberts suggests that Salford was really made up of a number of relatively self-contained ‘villages’, each with a certain infra-structure:

With cash, or on tick, our villagers, about three thousand in all, patronized fifteen beer-houses, a hotel and two off-licences, nine grocery and general shops, three greengrocers (for ever struggling to survive against the street hawker), two tripe shops, three barbers, three cloggers, two cook shops, one fish and chip shop (déclassé), an old clothes store, a couple of pawnbrokers and two loan offices (Penguin Books, Kindle Edition, p.14).

There are indeed references to some of these kinds of essential small shops/retail outlets in the novel of Love on the Dole. These include a grocer’s, a clog-shop, fish and chip-shops, pawnshops and pubs, as well as ‘two handcarts, one selling cooked ribs, the other fish’ (p.56) and an itinerant ‘second-hand clothes dealer’ (p.57). There is no mention of greengrocers, cook-shops or barbers (despite Greenwood’s father’s trade – see Walter Greenwood and his Father’s Trade (Hairdresser) *). Overall, though, these are mainly passing references, with to an extent the exception of the grocery. Mr Hulkington’s grocery shop is there in the opening and closing pages. On the opening two pages of the novel Mr Hulkington’s grocery gets quite extensive coverage:

5.30 A.M. A drizzle was falling.

The policeman on his beat paused awhile at the corner of North Street halting under a street lamp. Its staring beams lit the million globules of fine rain powdering his cape. A cat sitting on the doorstep of Mr Hulkington’s, the grocer’s shop, blinked sleepily . . . Lights began to appear in the lower windows of the houses. The grocer’s shop at the corner of the street blazed forth electrically, the wet pavement mirroring the brilliance. Unwashed Mr Hulkington, the gross, ungainly proprietor, shot back the bolts and stood on the step, wheezing, coughing and spitting on the roadway. He panted, shivered in the rawness of the morning, turned about and closed the door to stand behind the counter in readiness for the women who would come, soon, stealing like shadows, to buy foodstuffs on tick (Vintage Kindle Edition, pp.13-14)

The grocery appears to be part of the fundamental dawn setting of Hanky Park. The grocer himself is named, but he does not seem to make it into the ‘trinity’ of local worthies (or perhaps un-worthies) whom Greenwood lists: Grundy, Grumpole, and Price.

However, I note resemblances between Mr Hulkington and these three: each has a Dickensian-style name suggesting more or less directly their disagreeable nature and exploitative function. While the ‘elite’ three appear to help people, they only entangle them further, and that must surely be true too of the grocer – people must eat whether they have the money to or not (though equally, he must keep his shop in business). His bulk and bulky name suggest that Mr Hulkington anyway is not going hungry – as does his brilliant and expensive electric lighting against Hanky Park’s usual gas lighting. His suite of unhygienic habits suggest that he may also not be the ideal food retailer -but then in this part of Salford (or anyway in the world of the novel) he appears to be the only source of retail-food for home-cooking. The word ‘gross’ is used only four times in the novel – three times to describe Sam Grundy (pp. 24, 113 and 116) and once here for Mr Hulkington, suggesting a certain kinship. Buying food on tick seems also be a source of shame for women – as is going to the pawnshop for some – as they come secretively.

At the close of the novel Mr Hulkington’s grocery is still there as part of the essential repetitive backdrop to Hanky Park, where it seems nothing can ever change because of the cycle of harsh economic facts. The women are still secretive and if anything even less substantial than at the start of the story as they take their unaffordable food home under their shawls:

A cat, sitting on the doorstep of Mr Hulkington’s, the grocer’s shop, blinked at Ned, rose, tail in air, and pushed its body against Ned’s legs. . . . Lights began to appear in some of the lower windows of the houses. The grocer’s shop at the street corner blazed forth electrically. Occasionally, women, wearing shawls so disposed as to conceal from the elements whatever it was they carried in their arms, passed, ghostlike, the street corner (pp.255-6).

Given these opening credits, as it were, in the novel, one might expect Mr Hulkington’s grocery to play a reasonably prominent part in the narrative, at least as a setting for the necessary acquisition of food whether affordable or not. In some ways it is indeed threaded through the whole story (it is named or referred to nine times) but mainly in what we might call exterior shots – we never once see inside the shop or see Mr Hulkington selling foodstuffs or other goods or women buying them. Indeed, the key business of getting, managing and cooking food on a tight budget is little referred to, with one notable exception early on when unemployment has not yet bitten deep for the Hardcastles and others. Harry, having been paid and finished work at noon on Saturday, anticipates the rest of that glorious day, both for his own family and for others:

Hanky Park shed its dreariness; its grimy stuffy houses took on cheerful aspects . . . Over all was an air of well-being for the day was Saturday. Pay day. No scratching and scraping today; kitchen table littered with groceries; sugar in buff bags; fresh brown crusted loaves; butter and bacon in greaseproof paper; an amorphous, white-papered parcel, bloodstained, the Sunday joint; tin of salmon for tomorrow’s tea; string bag full of vegetables; bunch of rhubarb with the appropriate custard powder alongside. Ma rushing about, now to the slopstone, now to the cupboard stowing things away, now to the frying-pan on the fire where the dinner was frizzling . . . After handing his wages over and receiving his spending money, he, while waiting dinner, sauntered, unwashed, to Mr Hulkington’s, the grocer’s corner shop where swarms of noisy children were spending Saturday halfpennies. He purchased two penn’worth of Woodbines, then stood with the rest of the boys on the kerb, hands in pockets jingling his money. This was life! Nothing else was to be desired (pp. 55-56).

In the relatively good times, this Saturday feast followed by a Sunday roast is a weekly festivity (the bloodstained white paper parcel must come from a butcher’s but that is a shop we never see depicted in the novel). Mr Hulkington’s corner shop too is a site of luxurious if only ha’penny or penny purchases. Nothing richer can be imagined by Harry, apart from the visit the same day to the cinema with his fellow apprentices and on one occasion with Helen too, with further affordable food treats:

They’d have a great time, with the boys, at the pictures, tonight. He’d buy her a tanner’s worth of chocolate. There’d be the picture queue – always fun there – the fourpenny seats; perhaps a penn’orth of chipped potatoes each, wrapped in a piece of newspaper; wouldn’t be Saturday night lacking these (p.68).

But all those Saturday and Sunday food and purchasing pleasures soon disappear for Harry and his peers, for Helen, for the whole Hardcastle household and for practically every Hanky Park household as the spectre of unemployment manifests itself.

There are three further references to chips too, not as an extra treat but as signs of habitual deprivation, and indeed of its acceptance. Thus Harry cannot help but link the diet of Helen’s parents to other habits which put them below his conception of ‘respectability’:

They [Harry and Helen] turned into North Street; halted by the open door of No. 7 where Helen lived together with the remaining dozen comprising the family. A number of very young and very dirty children played in the gutter. Women passed, occasionally, carrying basins of fried fish and chipped potatoes leaving a pungent odour of the mixed dish in their wakes; lines of washing decorated the street billowing in the fitful breeze (p.44).

The paragraph implicitly links Helen Hawkins’ parents to unconsidered, unregulated and unaffordable reproduction which inevitably increases and sustains their poverty and reproduces it for their children, who are pictured as closely-spaced, dirty, and neglected (there was of course a general ignorance of family planning and contraception, but this was not total, and Greenwood did discreetly introduce some discussion of the topic into Love on the Dole – see ‘Call the Handywoman!’: Birth and Death in Hanky Park (1933-1937) *). Finally in the passage the whole area’s slum status is associated with a diet of bought-in rather than home-cooked food (the ‘pungent odour’ clearly suggesting an olfactory distaste for this food on Harry’s part). In an extended passage some twenty pages later Harry begins to bring to the surface of his mind his earlier implicit assumptions:

He was interrupted by Helen Hawkins who was passing, carrying a basin of the inevitable chipped potatoes. Tom Hare lowered his voice as Helen, a timid smile on her lips, paused in front of Harry. The others moved farther away to listen to Tom’s story. Now and again they chuckled . . . somehow, all that Tom Hare had said seemed related to the basin of chipped potatoes in Helen’s hand, related in a vague way, yet related. The food typified her home: the Hawkins family seemed to live on nothing else. Ach, her mother was too lazy to cook proper meals: she and her husband were too fond of going out boozing in the company of Tom Hare’s parents and letting the house go hang. Suddenly, it dawned on Harry that Helen’s environment was precisely that of Tom Hare’s! A fearful thought flashed through his brain. Was it conceivable that Helen might have to listen to or even witness the drunken sexual behaviour of her parents? It was revolting, shameful. It gave place to others. Did Helen sleep in the same room as her parents or was her bed in the back bedroom? Did her grown brothers sleep in the same bed as she? ‘Like me and Sal?’ a voice in his brain added the question (p.62)

Tom Hare, whom Harry always regards as crude and dirty-minded and certainly not respectable, talks about sex in a debased way at all possible opportunities and though Harry does not hear what he says this time, he knows that it is about Helen’s parents’ all too open and drunken sexual habits (the Hawkins house is too small and overcrowded for any privacy). In his thoughts he cannot help link – though he knows it is an indirect link – the fish and chips eating with other circumstances of slum life and deprivation. However, we should note that while he regards (rightly) his own family as more respectable, he also knows that aspects of their lives, including living arrangements, are forced upon them by lack of means, not chosen. Fish and chips might be excusable as an occasional quick meal, but Harry fears that the Hawkins family ‘live on nothing else’. There is one further reference to fish and chips when a working man too makes it clear on his return home at the end of the day that he thinks they are a sign of his wife’s slovenliness:

‘Ah suppose it’ll be chips’n’ fish agen, eh? Y’ll have had no time t’ do any cookin’, eh? Ah’.…’ He slammed the door; a moment later, a child, carrying a basin, appeared and made a bee line for the fried fish shop (p.241).

Robert Roberts concurs with Harry (and perhaps Greenwood?) that frequent eating of fish and chips carried a certain stigma and marked a fall from a certain working-class status, though he complicates this a little with his distinction between fish and chip shops and ‘cook shops’:

in the early years of the century only the ‘low’ in the working class ate chips from the shops. Good artisan families avoided bringing them, or indeed any other cooked food, home: a mother would have been insulted. Fried fish without chips one could already buy from cook shops. One could eat at these shops or take out a fourpenny hot dinner in a basin. Many working women among our three thousand or so inhabitants took advantage of the basin meal; engaged as they were all day in the weaving, spinning and dyeing trades, they had little time to cook, or indeed to learn how to, since their mothers before them had often been similarly occupied in the mills. This contributed, I think, to the low culinary standards which existed in the Lancashire cotton towns before the first world war (The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century, p. 105).

One notes also that Roberts thinks about some of the reasons why working-class women in the city could not easily or habitually commit to regular cooking or the development of cooking skills, whereas Harry (and perhaps Greenwood?) puts it down to a lack of standards.

It may seem odd that having said that Love on the Dole has less to say about shops and food shopping than one might expect, I have now spent some two thousand words on the examples it does have, and the insights they give us into Hanky Park society! In fact, I have been surprised at how much reference, even if passing, there is to small shops in Love on the Dole, and this has illuminated a number of issues about place, class and food. Nevertheless, I still think the topics of shops and the buying of food seem under-represented in comparison with the attention given by Robert Roberts, who has a whole chapter on ‘Food, Drink, Physic’. Roberts begins his discussion of food with this statement:

The minds of the very poor of the time were constantly preoccupied with feed – where was it to come from tomorrow, or even today? How best could a pittance be spent? (The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century, p. 100).

This is perhaps more what one would expect. Indeed Roberts from his own experience sees the small shop as a centre for the life of such working-class communities in Salford in the first few decades of the twentieth century, as well as a key vantage point for the social observer:

This is a book made much from talk, the talk first of men and women, fifty or more years ago, of ideas and views repeated in family, street, factory and shop, and borne in mind with intent! The corner shop, my first home, was a perfect spot for young intelligence to eavesdrop on life. Here, back and forth across the counters, slid the comedy, tragedy, hopes, fears and fancies of a whole community: here was market place and village well combined. Only a fool could have failed to learn in it (The Classic Slum, pp. 8-9).

3. Shops in The Cleft Stick (1928-32/1937)

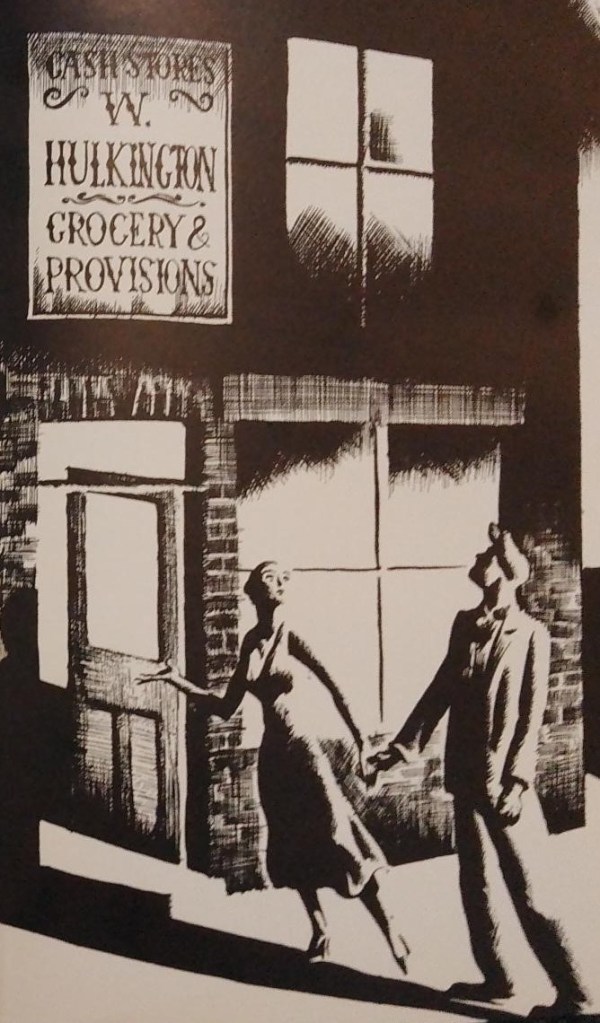

I. Hulkington’s Grocery & Provisions

In fact, in Walter Greenwood’s first portrayals of Hanky Park there was a less ‘flat’ society, though by no means the whole class range was portrayed, and small shops and their owners did get considerably more attention. These portraits were among the stories he wrote while unemployed between 1928 and 1932 and which were not, in the main, published until four years after Love on the Dole when they came out as a unified short story collection in 1937 titled The Cleft Stick or ‘It’s the same the whole world over’, with illustrations by Arthur Wragg. Of the fourteen Cleft Stick stories, ten are certainly about working-class households, though with a range of economic circumstances, and including five which are very impoverished. However, there are also two stories which focus on shops and their owners, who have risen from their original class and have perhaps moved in some ways towards a more middle-class self-identification. These are the sixth story, ‘A Little Gold Mine’ about a grocery, and the eighth story, ‘All’s Well That Ends Well’ about not just a fish and chip shop but a successful small chain of six shops, with indeed considerable pretensions. Both are substantial stories, the first of twenty-two pages, the second of twenty-one pages.

‘The Little Gold Mine’ gives us a stronger focus on Mr Hulkington and his business than does Greenwood’s novel, though he can hardly be called the hero of the narrative nor even exactly its protagonist. While still deeply unattractive, as in Love on the Dole, and an exploiter himself, he is also a kind of victim. I think the still quite persistent thread of references to Mr Hulkington and his grocery in Love on the Dole does originate in this earlier short story where he has a certain existence in his own right, if a short-lived one. Indeed, one of the things which The Cleft Stick stories show us is that there are elements of a metaphorical palimpsest in Love on the Dole, that is (originally or literally) a new manuscript written over the erased or partially erased text of an earlier manuscript. The prominence of the over-written material varies, sometimes being wholly obscured, sometimes being still present, and sometimes showing traces which do not necessarily reveal their original extent or emphasis.

Mr Hulkington’s shop is introduced in the earlier story in a way resembling and indeed clearly contributing to its later presentation as part of the pre-dawn scene of Hanky Park:

Night still had an hour of life and North Street stood black and deserted. The knocker-up with his long, wire-tipped pole had just finished rapping on the bedroom windows of the last house in the street. Lights began to appear behind the yellow paper blinds of the cramped houses, then the shop at the corner, owned by Mr Hulkington, flashed its electric brilliance on to the dark, damp pavements (The Cleft Stick, p.79).

This seems just as atmospheric as Greenwood’s later version, and every detail gives not just a visual impression but tells the reader something of social significance: the knocker-up exists because no one can afford a alarm-clock, the paper blinds because no one can afford fabric ones or curtains. In contrast Mr Hulkington can afford the exceptional brilliance of electric light – and presumably he opens early to catch (or possibly ‘oblige’) the women who must come early to get what breakfast they can afford for their menfolk and children. We do not, though, get much sense of Mr Hulkington’s social origins nor his status now, though he is clearly able to run his business effectively. He has not adopted a new dress code (in Wragg’s illustration he wears no jacket but a striped shirt and a muffler) nor any outside interests nor sought local political position as far as we can see, though he has, as we shall see, acquired a lawyer and a property agent. So far, this opening is, just as in the opening of Love on the Dole, an exterior shot of the grocer’s shop, but in the next long paragraph our viewpoint moves inside the shop, giving us the interior detail of shops and shopping which we never get at all in the novel. I will not quote the whole paragraph, but enough to give a sense of the material realism which Love on the Dole does not offer in its allusions to shops:

You could buy almost anything here from provisions to patent medicines . . . There were shelves all round the shop full of jams, sauces, packet goods and dummy advertisement boxes: there was a hand-worked bacon cutter on the counter and a pair of greasy scales which weighed bacon one minute and a half-penny of sticky sweets the next . . . The window was crammed with tinned stuff and boxes of toffees at which the hungry kids of the neighbourhood would stare. Flies abounded here, crawling onto the confectionery, the bread, the cheese, bacon and on everything, except, it seemed the fly-papers hung in the windows and from the shop’s ceiling (p.79).

Of course, this is not neutral description – it implicitly emphasises a number of deficits with Mr Hulkington’s grocery including the large number of ‘packet goods’ rather than fresh foods, and also some things which might prevent it from gaining a modern British retail hygiene certificate grade 5: the weighing of different foods in the same scales and the large population of flies on what fresh food there is, mainly bread, bacon and cheese. Next to this visual description is added a distasteful olfactory one, more extensive than the Love on the Dole objection to fish and chips (maybe, like me, Greenwood was not fond of malt vinegar):

The stench of the shop hit you in the face when you opened the door. There was no particular odour; it was mixed, as mixed as the bottled pickles and as tart as the vinegar whose cask was on the extreme edge of the counter (p. 80).

The physical points having been made, the narrative moves on to some of the economics of Mr Hulkington’s shop. Conspicuous notices declare that ‘FOOD RELIEF TICKETS ARE TAKEN’ and that it is pointless to ask for credit, though the narrator adds that this can be ignored since if Mr Hulkington refused credit ‘he would soon have had to close his shop’. His three dawn customers are three women, named as Mrs Cranford, Mrs Jike and Mrs Glynne (the first two are in Love on the Dole and other Greenwood stories, but we never meet Mrs Glynne again though she is important in this story). Mrs Cranford requests purchases in specific detail: ‘Ounce o’tea, two ounces o’bacon – lean – and a pennorth o’milk’ (she brings a broken-handled mug to carry away the last item in, p.81). Clearly she wants very small quantities of each food. For those brought up after Britain largely (if not wholly) switched from so-called Imperial weights and measures to metric measures in 1985, an ounce was the smallest unit of weight and the equivalent of just 2.835 grams, so something like two rashers of bacon or maybe nine tea-spoons of loose-leaf tea.

These are evidently the largest quantities which Mrs Cranford can afford per day since the smaller the quantity the lower the price. Robert Roberts comments on this kind of household economy and the challenge it presented to small shopkeepers:

The very poor never fell into debt; nobody allowed them any credit. Paying on the nail, they bought in minimal quantities, sending their children usually for half a loaf, a ha’p’orth of tea, sugar, milk or a scrap of mustard pickled cauliflower in the bottom of a jar. Generally, two ounces of meat or cheese was the smallest quantity one could buy; to sell less, shopkeepers said, was to lose what tiny profit they got through ‘waste in cutting’. Yet poor folk would try again and again, begging for smaller amounts – ‘Just a penn’orth o’ cheese – to fry with this two ounces o’ bacon’ (The Classic Slum, pp.103-4).

Clearly, Roberts and Greenwood do not quite concur on the access of the very poor to credit in local shops, though each implies it was a common and necessary system in small shops. Both give a similar picture of the need to buy on the smallest possible scale. Mrs Cranford’s bacon order conforms to Roberts’ account of the smallest quantity of meat a shop could sell without self-inflicted economic loss. There seems to be a possible clash between the small scale of Mr Hulkington’s sales here and his fabled wealth – but later accounts in the story of how the shop trades overall seem to discount this possibility and confirm its status as a ‘little gold mine’.

Mr Hulkington noticeably serves first Mrs Cranford and then Mrs Jike and only turns to serve Mrs Glynne after the other two have left the shop. This turns out to be precisely because of her credit status (and her daughter). Mr Hulkington’s ledger says that she owes money on goods purchased over the last five weeks. Worse, he turns out to be her landlord too, and she owes twelve weeks rent. Her husband has been out of work and her daughter Nance has only been working three days in the last weeks, because Regent Mill is on short time. Mr Hulkington is very interested in the economic plight of the family, in a sense: ‘You know how I’m fixed; this shop and all the houses I own. Your Nance would be well looked after’ (p.83). There are some potential obstacles to Mr Hulkington’s plan for himself and his properties: as he full well knows, Nance is not interested in him but in a young man called Harry Blake who works in a foundry, and even Mr Hulkington considers that his own age might be an impediment. He does not, though consider his appearance which is also against him, as the reader knows, having just had an expansion of the descriptions in Love on the Dole when he comes to serve the three women at the counter:

There appeared a mountain of a man whose monstrous stomach was inadequately concealed by a dirt-and grease-stained apron which once had been white. His eyes were heavy-lidded and protruding, his upper lip though pendulous, was not long enough to conceal the two middle incisors; his lower jaw and neck were enormous so that when the shadow of his head was thrown against the wall it had the outline of a huge egg (p.81).

He is positively monstrous and lives up to his name of Hulkington (though perhaps the further destruction of his character through caricature is just too easy a trick on Greenwood’s part?). In pressuring Mrs Glynne through his patronage (blackmail?) to ‘encourage’ Nance to marry him. Mr Hulkington shows that he knows very well that she is unlikely to marry him willingly, though this also sparks in him a moment of self-pity centred on imperfectly connected understandings of different kinds of ‘value’:

Oh, it was agonising to have to admit that you were wanted, not for what you were, but for what you possessed, aye, bitter truth, and sometimes not to be wanted at all’ (p.84).

This grants Mr Hulkington an unusual moment of inwardness, though not the only one, but seeing into his thoughts and feelings does not improve his image. He still lacks self-awareness in many respects.

Other potential obstacles to his wishes are Nance’s own hopes and perspectives on life. She finds Harry Blake attractive and wishes to be Mrs Harry Blake, but is well aware that he is content to be admired by a variety of girls and that he has not singled her out for any particular commitment. She often eagerly reads what Greenwood (snobbishly?) describes as ‘a cheap woman’s magazine, the kind devoted to highly emotional fiction’ and she hopes that a melodramatic turn of events of the kind it features in which a hero rescues a heroine from a villainous suitor will one day commit Harry to her alone. Greenwood shows his view of her reading as uncritical by describing it as unthinking consumption: ‘she was devouring the text’ (p.84). Nance’s mother takes a markedly different view of the uses of ‘romance’ and marriage:

Life’s a funny thing for the likes of us, Nance. When you’ve lived as long as me you’ll find there’s nothing so important as money . . . that shop’s a little gold mine, and he’s got plenty of money besides. Aye, and he says he’ll leave it all to you if you married him’ (p. 87).

Besides, she says, Mrs Bull has given her expert medical opinion that Mr Hulkington is killing himself by habitually drinking whisky neat. The thing which suddenly sways Nance from her conviction she’ll never marry Mr Hulkington is that her romantic investment in Harry proves ill-founded: he stands her up outside a dance-hall and when after waiting for one and a half hours she spots him sneaking home he tells her he is not her exclusive possession and indeed that any idea of getting wed is ‘off’. Nance goes home furious and tells her parents she will marry Mr Hulkington. They marry quickly at the local registry office.

It is only then that Nance (who, as we have seen, is not so far an instinctive thinker) realises what she had done: ‘That huge gross mountain of a man was her husband’ (p.90). To mark this special day Mr Hulkington has done an unprecedented thing – he has closed the shop. In a surprisingly explicit exchange (which the BBFC censors would certainly have never allowed near a film studio) Nance begins to lay down some rules and quickly establishes dominance over the man she has deliberately married because of the power which money gives him: ‘Remember, there’s to be no messing about with me . . . go and open the shop’ (p.91). There clearly has been no pre-nuptial contract to this effect, and Hulkington’s expectations of what is involved in marriage with Nance are quickly overturned – but he makes no effective protest then or ever and is lost. Nance bolts the bedroom door every night and Hulkington sleeps elsewhere – and, as we see, Mrs Bull is right about the neat whisky: he is in ‘the depths of despondency’ and only frequent whole tumblers of whisky seem able to address his pain.

The reversal of power between them is absolute. Curiously, Mr Hulkington now shows a kind of innocence: despite his misery what he dreads most is Nance leaving him and he does anything to please her. She is very pleased not to have to get up and go to the mill in the mornings, is pleased too to have a private bathroom and is amazed by Hulkington’s unusual connection to the electricity supply: ‘It was a novelty to live in a place where there was electric light. She had played with the switches for minutes on end’ (p.92). What most pleases her though is money and the things she can buy with the notes which Hulkington freely disburses: ‘the imitation Persian lambskin coat and the expensive Tyrolean hat’ (p. 94). She fills her time by going out into Manchester, enjoying especially theatre trips and the pictures. She always goes alone, leaving Hulkington to continue running the shop which together with his rental interests brings in all those pound notes which indeed truly attract her. Hulkington is very unhappy about this going-out habit, but Nance has said she will leave him and go back to work at the mill (a no doubt entirely unlikely scenario after the satisfaction she gets from her new life), if he is not satisfied with her as his wife. This prospect fills Hulkington with fear and deepens his submission and complete compliance.

One day while out she meets Harry Blake by chance and they agree to meet every Saturday afternoon in town. Nance says she will pay for everything. As readers can immediately see from his inner thoughts, Harry’s attitude to Nance has in no way changed, but her context has and with him that is key:

He experienced a sudden surge of invigorating warmth to remember her comparatively affluent circumstances and her generous nature. Oh, he was tired of going out to work, anyway. And you never knew. Hulkington was decrepit (p.95)

Nance’s invitation instantly suggests to Harry that he can take up a position in relation to Nance which is the same as her relation to Hulkington: one based solely on access to money and involving no other bond or obligation whatsoever. Curiously, Nance now adopts a different manner towards her husband, which is reported from his point of view:

Something had happened to Nance which he could not fathom. She even smiled at him nowadays, cooked his meals herself, always saw that his whisky was handy, and she went about the house singing. But though she smiled at him sometimes she would not encourage him in any other way (p.96).

Hulkington on the whole finds this new attitude even more troubling, but he is grateful that she does not in any way try to curb his whisky consumption, his only way of coping. However he does begin to wonder if he should drink less – he is suffering from palpitations. Best, though, he thinks, to go carefully, ‘to break the habit by degrees’ (p.97).

Sadly, Mr Hulkington does not get time to try to carry out his resolution, for that very day he tried to get up from his armchair to respond to the shop-bell and collapses with a pain in his chest and with ‘his lips blue’ (p.97). Ironically, it has been Nance returning from one of her outings who makes the shop bell jangle. She hears Hulkington’s collapse and sees him unconscious, so runs to fetch Mrs Bull the handywoman from her house (a ‘handywoman’ was a source of medical wisdom, if not the possessor of any certificates – see ‘Call the Handywoman!’: Birth and Death in Hanky Park (1933-1937) *), who tells Nance to next run for the doctor. Alas, as Mrs Bull immediately sees, there is nothing to be done; this the doctor can only confirm while saying there must be an inquest. Mrs Bull and two passers-by who have helped lift the body feel it only fair to finish the bottle of whisky which Mr Hulkington had at hand: ‘Neat?’ asks Mrs Bull, with grim hypocritical comedy. The inquest verdict is that death is caused by ‘fatty degeneration of the heart accelerated by alcoholic poisoning’ (p.99)

Despite Mr Hulkington’s promise that he would leave everything to Nance he has in fact made no will, but everything does of course go to her as his wife. However, Hulkington had made no other preparations for such a handover and Nance ‘did not understand a thing about the settlement of her husband’s estate’, being overwhelmed by ‘letters from her lawyer, bills from the wholesaler, accounts from the property agent’ (p.99). She hopes that Harry will instantly offer to marry her and fulfil her long-cherished dreams. Soon both for practical and no doubt other reasons she appeals to Harry to help sort out these puzzling business matters. Harry however seems very reluctant: he says people will say he is running after her because of her property. Nevertheless, his reluctance is soon overcome and the two marry – Nance insisting that in addition the shop and all the other property is explicitly transferred to Harry’s name by her lawyer.

Harry at first plans simply to take life easy – he naturally gives up his job at the foundry, and plans to let Nance run the shop while he gets up late and goes out of an evening with his mates. But he soon gets increasingly fascinated with the shop as he realises while watching Nance serve behind the counter that ‘every sale meant a little profit’ (p.101). Not only that but he notices some alarming behaviours on her part – she gives slightly generous measures on weighed goods and often extends the credit of women whose husbands are out of work. Perhaps worse, she supplements the household allowance he gives her by sometimes taking more money from the till: he immediately puts his husbandly foot down – ‘You’ll have to stop this Nance. It won’t do at all’ (p.102). Just as the power relations between Mr Hulkington and Nance were quickly reversed, so too are those between Nance and Harry: now he has put his mind to it, his control of her and all her goods cannot be undone. Her romantic dreams are not fulfilled: she realises that what Harry has fallen in love with is money. Indeed, she thinks that she was much better off with Hulkington, ‘who was her abject slave’. However, so fully has she absorbed the illusion of romance from her magazine reading and, no doubt, from a wider culture of the dreams suitable to women, that while fully understanding the truth she can continue as long as she never has to face it:

What did it matter if he was treating her as an employee, as a shop assistant? What did it matter if his devotion was transferred to the business of gain? She could not be jealous of money as a rival even though she saw his ardour with it every time he fingered the treasury notes before taking them to the bank, or the painstaking way he wrote out cheques. Nothing mattered so long as she never heard him say, in so many words, that he did not love her (p.105).

This is clearly a kind of ‘doublethink’ before Orwell had first coined the word in 1949: her reasoning about the truth is hard-headed, but counteracted by the existential need she feels to maintain her illusion (for an introduction to the concept of ‘doublethink’ see the wikipedia entry https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doublethink). For his part, Harry also exactly understands the situation. At the very moment when his real mental attention is absorbed by a plan to evict the Jackson family, who are behind with their rent, from the next door property and turn it into a drapery shop, he in passing thinks ‘better humour her; better make a pretence of love’ (p.105). It is a cruel ending, yet we see Nance apparently happy.

Love on the Dole has a strong interest in romance in various ways: it is something which motivates aspects of Sally and Helen’s behaviour, even though both know that it is at times an illusory hope, and indeed partly a product of ‘novelettes’ and the cinema. Equally though, in showing how hard or even impossible it is for love, feeling, romance to survive in the real economic and social conditions of Hanky Park, the narrative is an anti-romance one or even an antidote to romantic delusion. The same duality of romance is powerfully there too in ‘The Little Gold Mine’. It motivates Nance yet she still marries Hulkington, who in turn has ignored all the conditions of romance, yet hopes it will come to him; it keeps Nance married to Harry despite her knowledge of its failure to deliver in the world of reality. But it is really the iron hand of economic necessity which rules fundamentally in Hanky Park, and one might say that Harry Blake sees that – except that actually he transforms even money into an object of romance. However, it seems hard to imagine that his avarice will bring real satisfaction any more than his wealth did to Mr Hulkington.

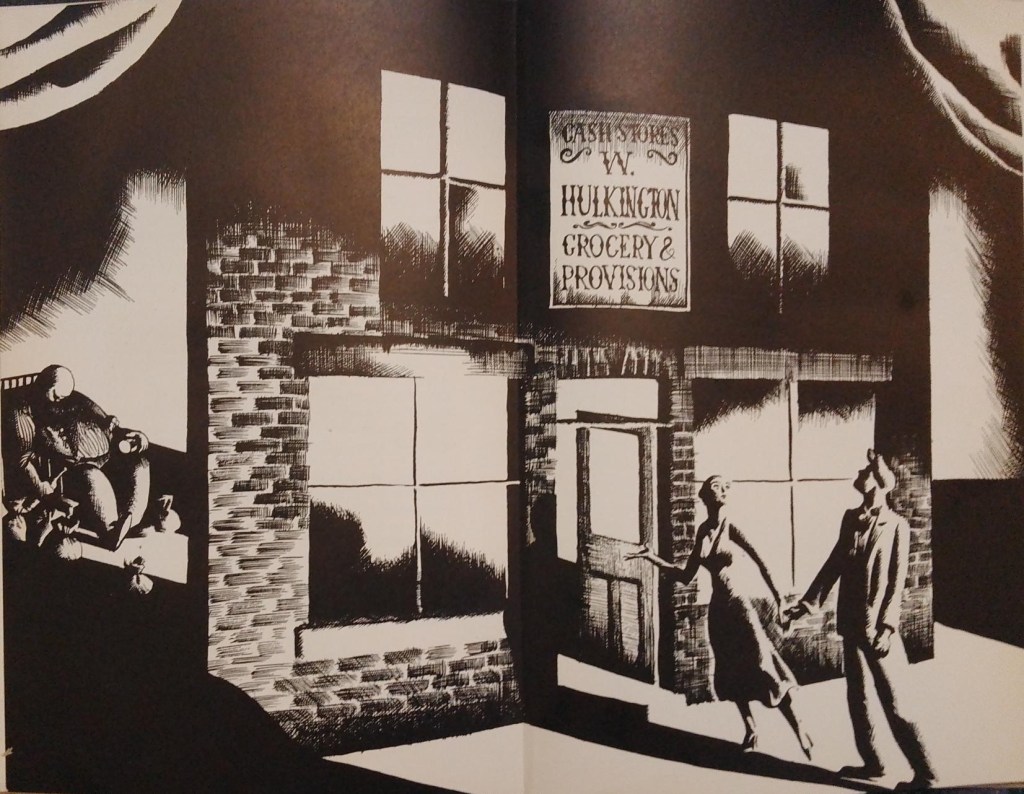

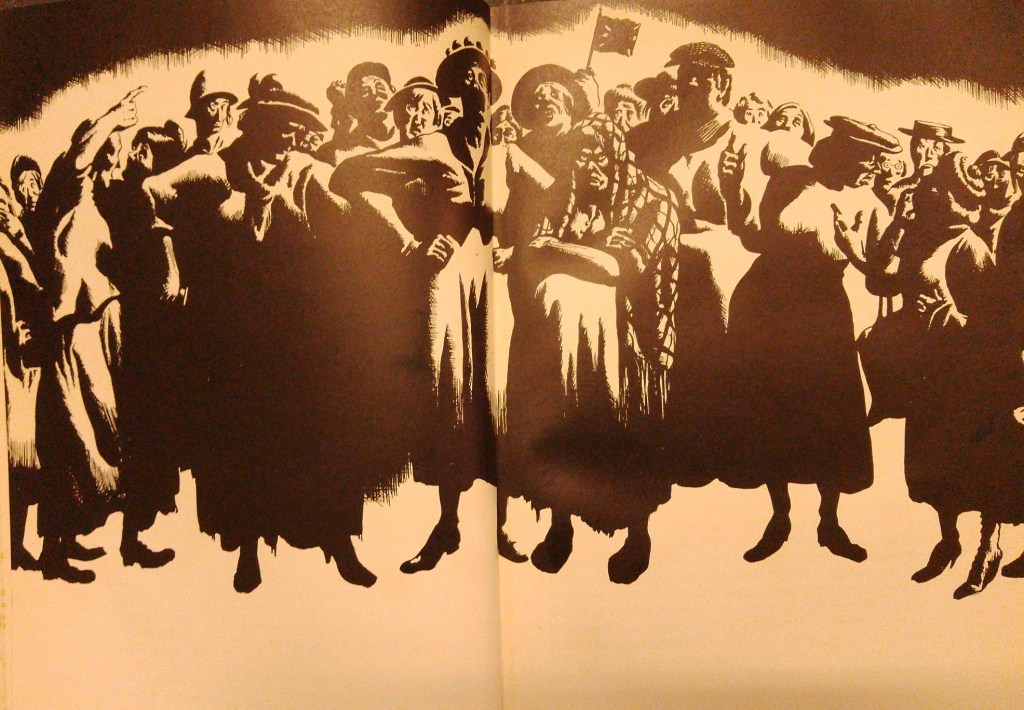

With every Cleft Stick story there is of course the free bonus of Arthur Wragg’s accompanying illustration, which always provides a highly-realised visual interpretation of Greenwood’s text (I am sure that Wragg read and digested each story with great care and attention). These illustrations (nearly) always manage to condense the whole narrative which Greenwood has had to unfold through a plot across time into a single dramatic scene which expresses all the essentials. That is the case with the illustration for ‘The Little Gold Mine’, which indeed uniquely among the drawings in the collection actually explicitly references theatre.

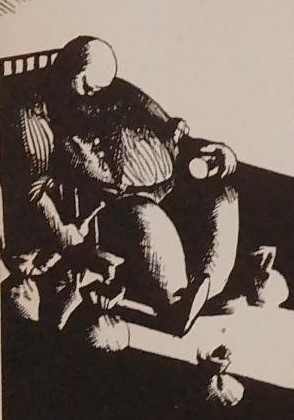

While Love on the Dole sees Hulkington’s shop wholly through its exterior and Greenwood’s ‘The Little Gold Mine’ story sees it wholly through its interiors, Wragg chooses to show both an interior and an exterior view simultaneously by reducing the solid substance of the shop to a flat façade which the viewer can see round, as well as through. In fact I think it would be fair to say that the shop is imagined as a theatre flat, a piece of scenery. This theatrical reference is reinforced by the swags of curtain in the two upper corners of the scene, which look like proscenium curtains. Perhaps the lighting too is theatrical, with the spotlights casting deep shadows around the three characters on stage, as well as evoking Hulkington’s bright electrical lighting. Certainly the image draws on Wragg’s love of chiaroscuro – sharp and extreme contrasts of light and dark in painting. Hulkington’s electric light from the shop is the only illumination in this night-time (or is it just pre-dawn?) scene, yet it paradoxically accentuates some very dark areas – including the upper storey and the interior of the house around the armchair in which Hulkington is slumped.

What we do not get is any representation of the shop as shop – there are no provisions displayed in the windows, as described in the opening paragraphs of Greenwood’ text, nor apparently any area behind the front door where selling and buying could take place. The goods themselves seem not to be key elements in the drama for Wragg, which is true too for much of the written story, but nevertheless some elements of buying and selling still run through the whole narrative. Perhaps in the drawing the sign announcing ‘Cash Stores’ and ‘Grocery & Provisions’ is enough to signal the function of the façade, the property which engages all the principal actors. Perhaps indeed all three seek things which are more signs than things of substance. The only things inside the shop / house are those close to Hulkington’s armchair and these consist of five bags which I take to be money-bags. Though in the story we see Hulkington giving Nance pound notes these more substantial moneybags might represent the actual weight of small coinage with which the grocer’s customers actually pay him, or equally might represent more graphically the status of the shop as ‘a gold mine’. The only other objects are those key properties or goods (though they do him no good) for Hulkington: his whisky tumbler and one of his bottles of whisky. He is not in full control of either: since the tumbler is below the horizontal, if there is any whisky left in it, it will be flowing onto Hulkington’s clothes, and the bottle while upright looks as if it might fall from his hand at any moment since he seems to be asleep and/or in a stupor (or on the point of death or even dead?). See detail below.

In fact, Hulkington’s posture raises the question of when in the narrative this scene is set, or perhaps rather how it encapsulates the whole story in a moment. There is not actually a moment in the written story when Nance show Harry what a good proposition Hulkington’s is while Hulkington is safely stupified. However, I think we can reasonably say that even while her husband is still alive the idea has occurred to Nance of replacing Hulkington with her true love Harry and that they shall both live happily every after on the proceeds of their little gold mine. Wragg shows Nance inviting Harry in while Hulkington is still in the process of his alcoholic demise. Again, the young couple at front of stage do resemble young lovers in a play spot-lit and inspecting their possible dream-house. However, I also note that while Wragg depicts Nance looking into Harry’s face while she gestures towards the one front door and has a foot raised to lead him in, he is looking not at her but up at that key sign: ‘Cash Stores . . . Grocery & Provisions’. See detail above. As in the case of all Wragg’s illustration to The Cleft Stick stories I think he has made a brilliant job of it, evoking all the events and emotions and nuances of Greenwood’s written story through just one condensed scene.

II . Babson’s High Class Fish Bars

One thing which is clear from the very beginning of this story, and which distinguishes it from ‘The Little Gold Mine’ is that Mrs Babson has adopted, or aspires to, a new class identity in line with the successful growth of her business:

In six of the busiest and most densely populated streets of Salford stood six shops all with a similar announcement painted on their windows: this said:

BABSON’S HIGH-CLASS SUPPER BARS

Fish, Chips, Beans and Peas

(Ribs Friday)

The proprietress of the shops was a rather attractive widow of forty who, at the age of nineteen, had been left quite unprovided for, and with a few-months-old daughter on her hands.

Putting out of her head all thoughts of further excursions into love and matrimony Mrs Babson had borrowed twenty pounds from her father and had opened a small fish and chip shop. By the time her daughter reached the age of twenty-one the original business had been so successful as to have encouraged Mrs Babson to open the other shops which now flourished under the management of the five responsible and as trustworthy women as Mrs Babson could find (p.110).

Though this does not quite tell us of Mrs Babson’s class-origins it implies that her deceased husband at least was not a man of any means at the point of his death, though if her father had a saved twenty pounds to lend her he must have been in an unusual position for a Salfordian. Later, we get some further detail confirming her origins, but even at this point we can see that Mrs Babson is a self-made woman who has made it through taking a risk, though hard work, through good judgement, through sensible delegation (noticeably exclusively to women), self-denial, and entrepreneurial skill. She has developed a sense of elite status and is anxious that her daughter inherits that perception, presumably to go along with her likely inheritance of the business (I also note that she is distinguished from Hulkington by having a ‘realist’ name with no particular implications, unlike his Dickensian caricature/satirical name). Later she reveals that, unlike Mr Hulkington, she has also acquired civic and political connections:

She was of sufficient importance locally to be on the official invitation list of all the Civic Functions out of respect for the contributions she had made to the funds of the Progressive Party (p.117). (4)

However, Mrs Babson is also aware that for women in Britain in the first half of the twentieth century their property and status is rather dangerously subject to the outcomes of ‘excursions into love and matrimony’. From the date when her daughter, Elsie, reaches her sixteenth birthday, Mrs Babson is keen to inculcate these concerns:

Mrs Babson said sternly: ‘Listen. Elsie, don’t you ever let me catch you encouraging those street corner louts. Do you hear? . . . Remember who you are. Constant acquaintance with the words “High Class” in the window, plus the satisfying growth of her bank balance, had, by this time persuaded Mrs Babson that the words were applicable not only to the shops, but to the proprietress herself (p.110).

Elsie does listen (though she wishes the guidance were issued less frequently) but cannot help noticing some of the young men who actually pass the fish bar or buy from it. Like Nance, Elsie is a patroness of certain dreams, but ‘even the twopenny novels of romance which Elsie devoured were beginning to pall’ (note Greenwood’s use of ‘devoured’ again – he has a set view of women’s popular fiction). Her mother says she must wait for a man who will keep here ‘in a style you’ve become accustomed to’, but Elsie does not seem to get sight of such a man, while she does see her peers in the neighbourhood making the acquaintance of actual and present young men. Indeed, one young man, Harry Williams (Harry again!) has started very regularly to eat his fish supper in Babson’s High Class Fish Bar, and he is very much to Elsie’s taste.

Mrs Babson is eagle-eyed and soon takes note. She warns Elise off this ‘good-for-nothing’ but is even more alarmed when Elsie defends him by knowing his exact wages: ‘two pounds five a week’. This is the same wage as Larry Meath draws in Love on the Dole and marks out Harry, like Larry, as a skilled worker, something like an engineer. This draws from Elsie’s mother an emotionally-blackmailing response which, again, Elsie is well-used to: that she has ‘slaved’ for twenty-one years wholly for her sake. This is followed up by a further focus on the preservation of the property – she will not stand idly by ‘and see all my hard-earned money going into the hands of any of this place’s street corner louts’ (p.112). One notes the rooted assertion that she is not of this place and that its people are in no sense her equals. However, in her next tactical move Mrs Babson actually reveals that she certainly is originally from this kind of background herself, and knows what it is to live on a skilled worker’s wages. This is in reply to Elsie’s assertion that she is not going to stay an old maid and that she envies the other girls going out with their young men. This is Mrs Babson’s reply and clearly draws on her own experience:

You, in your position, envying them? Just look at ’em when they’ve been married a year. Aye, and suppose you did marry this Harry . . . on his two pounds five a week. There’d be ten shillings a week rent – that’d leave you thirty-five shillings for food, clothing and everything else, for two people, yes, and that’s if he never came out of work. And it would go on for as long as you lived. You can’t tell me anything about that; I’ve had to do it myself. Don’t you kid yourself. They’ll be after you round here: it’s not you they want, they think they’re on a good thing . . . I’ve got ambitions for you (p.112-13).

No one could say this is not full of realist, and indeed real, detail about managing on even a skilled worker’s decent wage. The speech leaves no doubt that Mrs Babson herself does come from that working-class base and knows of what she talks. What may be more delusive is her set assumption that place absolutely equates to class and class to certain qualities. Thus she asserts that round here it will be Elsie’s inheritance the men will be after, not herself (though from a very different perspective, this echoes some of that other shopkeeper, Mr Hulkington’s, concerns). Her talk of ambitions implies that ‘suitable’ men from a better-off environment will not take money, property or inheritance into account – which may well not be a safe assumption on which to proceed.

Elsie, as the story makes clear, is a kind-hearted girl who does not like to upset her mother, and who does indeed take notice of what she says. Moreover, she sees the force of this particular argument from her own experience:

Her mother was quite right. You had only to look at the young married girls who came to the shop, with a basin in one hand and a child in the other, to see the difference in them from what they had been one or two years ago when, passing the shop windows on the arms of their fiances, they had filled Elsie’s heart with so much envy (p.112).

This echoes Harry Harcastle’s (or are they the narrator’s?) observations about the impact of marriage on working women in the novel of Love on the Dole:

The vivacity of their virgin days was with their virgin days, gone; a married woman could be distinguished from a single by a glance at her facial expression. Marriage scored on their faces a kind of preoccupied, faded, lack-lustre air as though they were constantly being plagued by some problem. As they were. How to get a shilling, and, when obtained, how to make it do the work of two (p.31).

Elsie makes it clear to Harry Williams that she is no longer so interested in him. He is upset by this rebuff especially when it becomes clear to his peers what has happened. They have their own interpretations of Harry’s motivations in being such a regular customer at Babson’s High Class Fish Bar. The story leaves Harry’s actual motivations somewhat ambiguous at this stage but reports that ‘Naturally Harry repudiated any such ambitions as were attributed to him, but the story was too good not to go the rounds’ (p.113).

That the story becomes a topic in local pubs leads to a crucial development in the narrative:

It so happened that while the story was being retold in the Duke of Gloucester public-house that there entered a stranger. a Mr Hector Pritchard . . . He was good looking and wore good, well-fitting clothes. Outside, standing by the kerb, was a new expensive motor car in which he had just arrived. This was not his, but a demonstration model belonging to his firm: he had returned from trying to effect a sale which had not materialised and, being disappointed as well as thirsty, had stopped here for a drink . . . He found himself listening to the story which was causing much merriment. After the story the talk turned on Mrs Babson and how much money she had and what her business was generally (pp.113-14).

Hector is feeling a little disillusioned with being a car salesman and scents an opportunity. He makes a discreet reconnaissance of all six of Babson’s High Class Fish Bars and driving along past the main shop notes through the window (he must have keen eyesight) that ‘both Elsie and her mother were attractive’. He swiftly comes up with a plan.

Just as Mr Hulkington has electric lighting in his shop, so Mrs Babson has a key piece of modern technology in each of her shops, a gas-engine which drives potato-washing machines and presumably saves much labour and increases the capacity of each of her fish bars. A gas-engine was (and is) an engine powered by gaseous rather than liquid fuel, likely in nineteen-thirties Britain to be coal-gas (see the Wikipedia entry https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gas_engine).

Oddly, the next day, though normally a very reliable machine, Mrs Babson’s gas-engine has broken down. Moreover, the mechanic she calls in can neither see anything wrong nor get it working. As it happens, at this point Hector parks his car outside and comes into the fish bar to ask if they could prepare him a ‘snack’ of some kind. Mrs Babson and daughter are immediately both struck by this stranger: ‘[Mrs Babson] was not accustomed to catering for such a class of customer . . . his manner of speech was as impressive as his suit and the motor car outside’ (p.115). Both she and Elsie feel they can certainly prepare him a meal. Over-hearing the mechanic who has struggled with the gas-engine declare that he is giving up for the present and going home for his dinner, Hector says that he knows a bit about machines and that really gas-engines are very simple machines – should he go down and have a look at it? Mother and daughter protest that the oil will spoil his clothes but Hector says he’ll just pop out to his motor car and put on his overalls (these turn out to be white and even more dazzling to the two women than Hector’s suit). After some tinkering, Hector turns the engine over and, hey-presto, it starts (of course, as the extra-attentive reader may have guessed, when Hector went out to get his overalls he also took the opportunity to remove the plug he had the day before put into the external exhaust pipe of the gas-engine, thus restoring it to running-order).

Mrs Babson is amazed at his cleverness and helpfulness and in this happy moment Hector takes the opportunity to ask her more about the business. Hector expresses himself duly ‘surprised’ that there are six shops in the chain and tells her that her ‘husband must be a very clever business man’. Mrs Babson enlightens him by telling how she has been a widow for twenty-one years and that it is all her own work. Hector is again duly ‘surprised’ that ‘an attractive woman like you’ has remained a widow. Hector has already pretty much won his prize but he has at least two more cards to play. The first is literally his card which he presents to Mrs Babson:

Mr. HECTOR D. L. G. PRITCHARD

Automobiles

Royal Automobile Club,

London

Secondly he says he has business in the area for a while and needs some lodgings. Of course, Mrs Babson says he must stay in their spare room. Her fate seems sealed.

She is not the only one. Elsie has been sent away by her mother to look after the front of shop while she talks to Hector, but Elsie notices his card on the table and it works a spell too on her, though she and popular fiction have partly pre-woven it:

A London Clubman! Just like the heroes in Penelope’s Weekly, who fell in love with shop girls and married them despite the antagonism of the hero’s blue-blooded family (pp.118-9)

Of course, the critical observer might think that Elsie as the potential inheritor of six successful catering outlets is not quite a ‘shop girl’ in the sense intended in the Penelope’s Weekly story. Nevertheless, she has correctly identified the class status which Hector would like the two women to place him in. One might think that an identity as a successful car salesman might be a big enough bait, but over the next few days of his stay he tells them of his sad fall from higher fortunes. He had been ‘up at Oxford’ when the Slump plunged his father’s business, ‘Henry Pritchard & Company Limited, chairman Lord Hotspur’ into sudden liquidation. The family is ruined, (apart from retaining the ownership of a small manor house in Shropshire) and Hector had to come down from University and take a job in the motor trade. Not only that but his fiancée had dropped him because of his family’s fall. He thus creates himself as both distinctly upper class and as a victim of the Depression (I assume that his back-story is a fiction, but as we later see he does nevertheless have considerable accomplishments which he has acquired somewhere). Hector says he learnt from the experience of this fall never to take prosperity for granted and that he does alright by selling a car or two at intervals.

Mrs Babson is by this point as putty, and confesses that she has been thinking for some time of buying a car (Elsie is silently a bit surprised because she has often suggested this and been told by her mother that they have no spare time from the shops for ‘gadding’). Hector says he will pass her details on to another salesman because he could not himself profit from any commission from someone he knows well. Naturally, Mrs Babson soon overcomes his absurdly conscientious scruples and has soon ordered on his recommendation a 25 hp Luxuria Saloon costing £550, and which he estimates will cost three pounds a week to run. She confirms all his hopes by saying she can easily afford this and then cannot resist telling him exactly what profits the six shops bring her in each week. There was not an actual ‘Luxuria’ car brand, but the Bank of England Inflation calculator tells me that £550 in 1932 would be the equivalent of £33,000 in November 2025 (which of course is the current kind of absurd price for a contemporary new car, if not an especially luxurious one). Nevertheless, very few in Hanky Park or Salford would be able casually to buy such a product, or indeed ever buy one at all under any circumstances (in Love on the Dole only Sam Grundy is named as the unique owner of a car, and much too is made of this ownership in the 1941 film version – see Sam Grundy’s Car: Sally Hardcastle’s Resistance (1933;1941)*).

A quite widely circulated unsigned newspaper article from 1932 suggested that under the current economic troubles even the wealthy were likely to be less confident about buying the kinds of ‘£400 – £500’ luxury vehicles they used to and that many were turning to smaller luxury cars such as those successfully being marketed by Triumph as ‘economy luxury cars’ (published for example by the Lytham Times, January 29, 1932, p.7, and one can’t help but think sponsored by Triumph in some way). There were examples of these brand-new ‘Triumph Luxury Saloons’ on the market that year for sale at £165 (the list price given by the periodical John Bull in the course of advertising a competition for which a free Triumph was the prize, 2 July 1932, p. 36). Clearly, however, the recession has not driven Mrs Babson to such personal economies and the car Hector recommends must be more like the larger luxury saloons which were certainly still available for the wealthy. Hector might have suggested something like those luxury saloons at around the £500 mark noted at the Scottish Motor Show – the Scotsman motoring correspondent wrote that there were ‘limousine models’ offering excellent value and quality offered by ‘Austin, Armstrong-Siddeley, Daimler, Humber Talbot and Wolseley’ (16 November, 1932, p.7). At the head of the page was indeed an advert for the Humber Snipe 80 giving a price of exactly £550.

Hector of course gets not only the kudos of helping Mrs Babson, but also his commission on the car and invaluable economic intelligence about just how well-off his victim is. Moreover, Mrs Babson institutes a new habit – regular outings in the new car with Hector. Elsie comes along in one of the back seats but despite the car’s luxury is in several ways an uncomfortable passenger, and increasingly so as the two up front begin to call each other by their Christian names.

Finally, Elsie cannot bear her exclusion and what she thinks the ridiculous behaviour of her mother, and brings things to a head when Mrs Babson asks her opinion of some expensive shirts she has bought in Manchester as presents for Hector. ‘Why’, remarks Elsie, ‘he’ll begin to think you want to marry him!’ (p.121). Mr Babson (correctly) reads this to mean two things a) that Elsie considers her mother well past the age of romance and marriage and b) that Elsie has her eye on Hector herself with marriage in mind. Mrs Babson:

Suddenly saw in Elsie not a daughter to be protected. but an antagonist, a rival from whom she required protection, and Elsie had on her side all the incalculable advantages of youth (p.121).

Accusations are freely exchanged, including about Mrs Babson’s previous mission to control Elsie’s access to men until a suitable one appears. Elsie asserts that she will now go out with Harry Williams, expecting to be able to carry out some form of emotional blackmail, but she has misread the situation: her mother is delighted now to see her out of the way and her own possession of Hector unrivalled. However, Elsie soon counter-attacks – she and Harry spend every evening at her mother’s home on the grounds that they are saving up to get married and cannot afford to squander money going out. This cramps her mother and Hector’s style and Elsie has developed a fierce and openly expressed hostility to Hector. Elsie develops a new blackmailing angle by arguing that if her mother gave her and Harry one of the six shops to manage this would speed up both their saving and their marriage plans. Mrs Babson hates the idea of letting a shop go, especially to be run by the local lad Harry. She remains adamantly opposed. However from her point of view Hector nicely speeds thing up by commenting that he cannot very well keep visiting Mrs Babson at her home if they are to be unchaperoned by her daughter. Soon Mrs Babson has got him to propose to her and idealistically asserts that all her assets will be in her and Hector’s joint names. The only thing he will not agree to is her wish for a big wedding (with invitations to ‘the Mayor and the highlights of the Progressive Association’): so they marry quietly at the Registry Office.

It surely seems obvious to the reader that Hector, having conned his way into Mrs Babson’s affections and hence fortune will run off with the money and be a thoroughly bad lot. This expectation is fulfilled in some ways and not in others. Hector seems to enjoy his role and live up to it well, without needing to con Mrs Babson out of anything further. She discovers that her chain of shops is not the only thing in her life, as they spend their honeymoon on a Mediterranean cruise:

the honeymoon revealed to Mrs Pritchard that she had been wasting the best years of her life in the pursuit of making money. Here was a new world, a fantastically happy world, one of ease, well-being and intoxicating love. She found a never-ending wonderment in Hector and his accomplishments, the way he spoke to the steward in French, the superb way he wore his evening clothes, his dancing and the thousand and one gentlemanly ways which captivated her (p.127).

Can it be that he is in some sense the real deal and that this is that very rare thing, a Walter Greenwood happy ending? The couple begin to plan for the future, with Mrs Pritchard wishing to make further inroads into ‘local society’ and Hector suggesting that they could expand the chain of fish bars by opening further shops. On their return Hector puts modern cash registers into each shop (leading to a ’10 per cent’ increase in takings) and manages the shops with ‘zeal and success’, opening one new branch very swiftly (p.127). His wife proposes that they should no longer live above the shop but move to ‘the residential quarter’.

Sadly, ‘the merest of chances’ ruins this idyll of prosperous married shop-keeping life, when someone from Salford now working in London is sent an old copy of the Two Cities Signal. He reads its account of the quiet Babson / Pritchard marriage and recognises what apparently is truly Hector’s real and full name: ‘Hector Llewellyn Glendower Pritchard’. Alas, he recognises it as that of a man wanted for abandoning his wife and three children and leaving them destitute to the care, such as it is, of the city of Salford authorities. The Pritchards’ new home is visited by police from the Two Cities force who arrest Hector on charges of desertion and bigamy, offences of which he is found guilty and sentenced in consequence to a stretch in prison.

Now it is Mrs Babson’s turn to be powerless and she turns to Elsie to confess not only that Hector has deceived her but also to say that to make it all much worse she is thus both not married and ‘going to have a baby’ (p.129). Harry, who as noted has remained a slightly inscrutable character – or is he just under-developed in the story? – makes the helpful suggestion that if he and Elsie were married people could be led to think it was their baby with no-one any the wiser, but of course they will need one of the shops to live in and on. Mrs Babson’s gratitude knows no bounds and their wish is granted. This is a story with a number of twists and there is one more to undermine any sense of a relatively happy ending:

As for Mrs Babson, she, when her child died soon after birth, felt that she had been tricked into the gift of the shop to Harry Williams – whom she had never liked anyway. But this only goes to show that some people are never satisfied (p.130).

The story title taken from the Shakespeare play is thus highly ironic: ‘ All’s Well that Ends Well’ (as of course is also the case for the play, the concluding marriages of which are highly problematic). Mrs Babson may have had a slight break from her commercial frame of mind but it plainly reasserts itself at the end. I will later come back in my article Conclusion to what Greenwood’s overall attitudes are to his small shopkeepers and what they can add to our critical understanding of his writing, identity and depiction of Hanky Park. Meanwhile we still have Arthur Wragg’s visual version of / commentary on the story to enjoy.

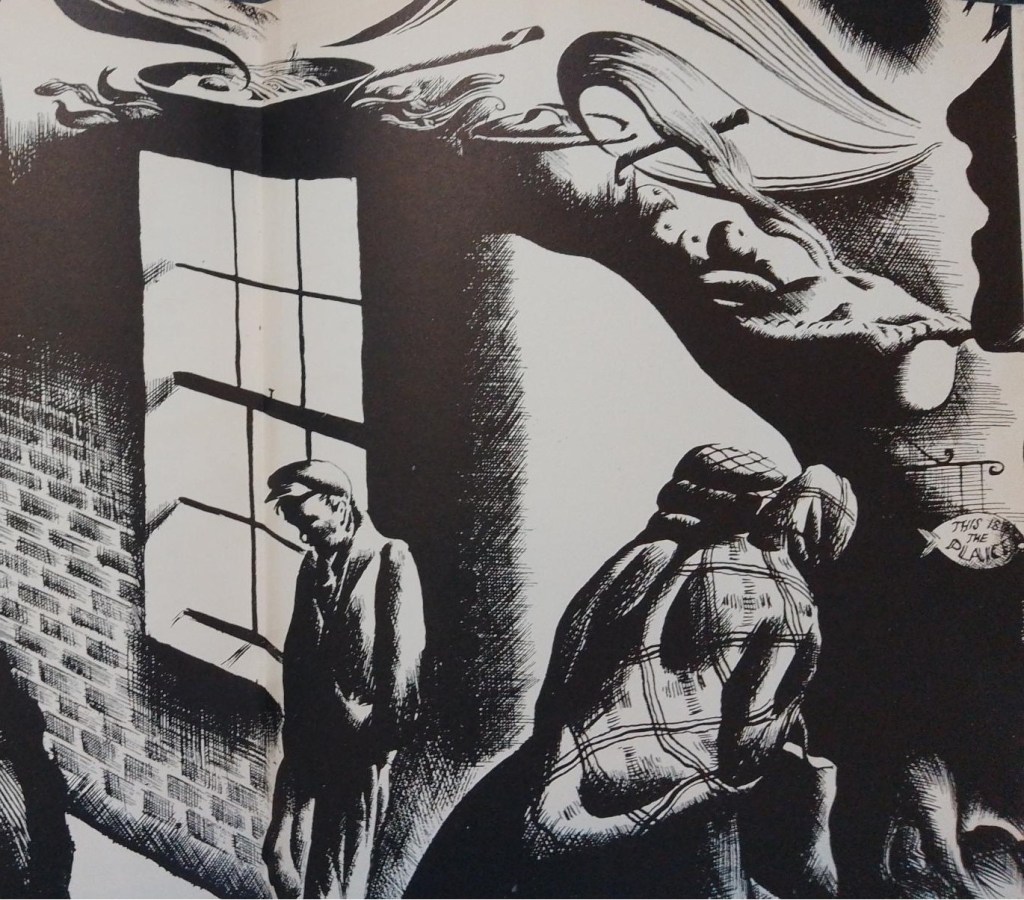

Here is his contribution.

Where for the Hulkington story Wragg used a playful but highly dramatic reference to a theatrical scene, here he brilliantly combines references to three visual genres into one: the family photograph, the shop-sign and broadly the heraldic crest. As shop-sign it naturally states prominently the name of the proprietor, and in this case their self-proclaimed sense of their superior status too. It is not a fish and chip shop but a ‘supper bar’, which I take it implies it is a dining-in rather then take-away establishment (indeed we have seen Hector asking to be served food there, though his word ‘snack’ may deliberately give a sense that he at first mistakenly under-rates the place). Wragg’s placing of the actual products the shops produce in a decorative lower border may perhaps accentuate a certain pathos – no-one could claim that fish, chips, beans and peas, or even ribs on Fridays, are exactly haute cuisine despite certain claims to grandeur made in the picture (indeed, I note that cooked ribs are one of the foods referred to as offered by a handcart in Love on the Dole). Family pride is also proclaimed by the profusion of aspidistras in pots above that lower border, but that famously indestructible house-plant is more, as Orwell asserted, the badge of middle-class respectability than that of a higher or wealthier class of property-owners. The profusion of the plants (well before positive indoor jungles of house-plants were fashionable) suggest a certain visual hybridity – they are partly suggesting the kind of props favoured by studio photographers to give background to their paying subjects, though on a much larger scale than usual, but also suggest a more purely decorative work suitable to a sign or kind of modernised heraldic banner. Even the border in which the text is contained suggests two different kinds of family respectability: on the one had it may suggest grander scroll-work, but in the other it is also plainly a representation of a sign of less grand domestic respectability in the form of a brass fire-fender with its scrolled metalwork at each end.

Meanwhile the human subjects of the family portrait are posed on and behind the domestic centre-piece of a sofa, women seated in front, men standing behind, suggesting hierarchy, and yet it seems rather uncertain whether standing men behind or seated women in front rank higher. The sofa does not look a very comfortable piece of furniture and both women sit very upright, with a noticeably large gap left between them. Indeed, the whole family group gives off a discrete air of discomfort: all four facial expressions seem to be under control but far from natural or relaxed. Mrs Babson disapproves of Harry for class reasons, and hence of her daughter’s projected marriage; Elsie disapproves of her mother’s marriage to Hector, and her former admiration for Hector has been replaced by intense hostility, while Harry says he never cared for Hector. Hector of course might well look nervous for he has much to conceal from everyone else in the group. Wragg portrays this unhappy family group with wonderful conciseness and immediacy. I think the illustration must be set in the sequence of the narrative before Hector’s bigamy is discovered and therefore before Mrs Babson’s wedding-gift of one shop to Elsie and Harry has been made, so the joint and unified family ownership of the business implied by their unification in the shop-sign cum heraldic badge cum family portrait is anyway somewhat of an illusion. I have not yet mentioned Wragg’s final brilliant, absurd touch: the two swans on marble pillars (or mock marble pillars?) ought if anything to signify royalty, which is definitely a claim too far, even for Babson’s High Class Fish Bars and its high pretensions.

III. ‘Any Bread, Cake or Pie?’: a Disappointed Customer at Hulkington’s, Babson’s, Shand’s and Jefferson’s