The film of Love on the Dole (1941) is remembered for several reasons: as a very good and classic British film, as a slightly unexpected critical and commercial hit during dangerous days in a war of national survival, and as a notable example of the ways in which film censorship in Britain in the thirties worked to control what films could be made and hence what audiences could see. Indeed, the last of these factors delayed the production of the film from the first proposal to the BBFC (British Board of Film Censors) in 1936 until its release in 1941, some six years later. The censorship was a crucial delaying factor in the realisation of the film, on which Greenwood himself was certainly keen, both because having been very poor for his first thirty-three years he liked to ensure a continuity of income from his work, and because he wanted his portrayal of poverty and unemployment to reach wide audiences and hopefully to influence and change public attitudes and local and national government policies. Indeed, as the war went on he developed his thoughts about what a new post-war Britain should look like and saw the eventual and quite unexpected film adaptation of Love on the Dole as playing a key part in bringing that about (see Walter Greenwood’s People’s War Manifesto (Sunday Mirror, 1941)). Despite the eventual making of the film and its great success it had been a tantalising project for film-makers for a number of years because while attractive, there were, as we shall see, a number of quite difficult obstacles to negotiate.

As well as the censorship question there is considerable evidence from discussions in the press that the actual type of story in the novel and play was also a challenge to producers and directors, as too was Greenwood’s own view of that story as a film. While the likely BBFC responses to certain kinds of material were no doubt always in film professionals’ minds, I think that particular ideas about the function of cinema as an entertainment medium also made film-makers approach the film of Love on the Dole with mixed thoughts. On the one hand it was an attractive project which, given the success of the novel and then the even greater critical and commercial success of the play, might do very well in the cinema. On the other hand it might prove challenging to audience expectations and to many film-makers’ own understandings of how successful film genres and individual pictures worked in the thirties. This article will trace the questions put in public to producers and directors, and the views of the project they expressed in their answers, all of which were followed keenly in newspapers between 1934 and 1940, when the film’s production finally began. This sustained press interest over six or seven years shows that newspaper editors and film columnists thought the future of Love on the Dole as a film was a matter of great public interest, partly in its own right and partly as a test case for the functions of cinema and its relations to censorship.

Some five producers and four directors and two stars are recorded as expressing opinions about the project, some strongly wanting to be involved, some expressing considerable reservations, hence my grateful if rather free adaptation of Pirandello’s 1922 play title, Six Characters in Search of an Author (perhaps with a touch too of ‘a Partridge in a Pear Tree’!). The two stars were in one case a key actor in the play of Love on the Dole, and in the other strongly associated with the play and the film by press coverage. They both aired their own views and encouraged others to progress a film of Greenwood’s (and Gow’s) work, which tended to keep the idea that there would and indeed should be a film version in the public eye over the six years of delay.

Five (potential) Producers

Four (potential) Directors

Two (definite and actual) Stars

For Image Sources see End-note 1. (1)

The first actor, and indeed an absolute British star of stage and screen, to express a public view about a future film of Love on the Dole was Gracie Fields (1898-1979). Her view was important partly because of her identity as a Lancastrian who had become a national star: this lent her comments local authenticity as well as national reach. Her star career was also a transformation from regional to country-wide recognition which any film of Love on the Dole would too need to achieve, as the play version had. The celebrated theatre and film critic Hannen Swaffer had published a very positive review of the play in the Daily Herald on 1 February 1935 – he was a keen supporter of the Labour Party, but not of Ramsay MacDonald and his National Government, so found himself in political sympathy with the play which explicitly criticises the National Government’s handling of unemployment. Swaffer also clearly thought the play a good and widely accessible piece of drama. Three days later Swaffer interviewed Gracie Fields about her response to the play which she had recently seen. She was enthusiastic, testifying to its Lancashire authenticity, and its capturing of ‘tragic facts’ and yet also its simultaneous ability to entertain through comedy (Daily Herald, 4 February 1935, p. 10). Swaffer had a sure feel for publicity and this interview was undoubtedly part of a plan on his part to support and promote the success of Love on the Dole through a Lancashire star. Thereafter Gracie’s endorsement was frequently quoted in brief in adverts for the two touring productions of Love on the Dole which visited almost every city in England over the next two years:

Seeing LOVE ON THE DOLE was a great experience. It was MARVELLOUS (Leeds Mercury, 19 June 1935, p.2).

It was Gracie who was first linked to the idea that there should be a film made of Love on the Dole. An article in the Leeds Mercury a few months later was headlined ‘Gracie May Play in Love on the Dole Film’ and referred to a plan by Greenwood himself to make this happen:

when I met Mr. Walter Greenwood, the author, during the week, he told me he was on his way to Capri to talk to Gracie about a plan to star her in a film version of the play (22 June 1935, p.5).

Greenwood did indeed go to stay with Gracie in her Capri home in June 1935, where perhaps there were further discussions about a role for her in a film version. However before that in March 1935 the Manchester Guardian reported Gracie’s continued if problematic interest in being in the film under the headline ‘ Miss Gracie Fields’s Plans: a Film Successor to Love on the Dole‘ The problematic part was her perception, or perhaps rather certain knowledge, that ‘film executives’ were opposed and would prevent her involvement:

The comedian has always longed to play Hamlet . . . And what does our great comedienne Miss Gracie Fields want to play? She wants the film people to let her act the heroine of Love on the Dole, the play made out of Walter Greenwood’s tragi-comic tale of Lancashire folk out of work . . . Mr Greenwood’s tale of life amongst the unemployed is nothing if not earnest, sprinkled as it so plentifully is with laughter. That is why the film executives won’t hear of it for Gracie.

‘It’s too political, they tell me,’ she said. ‘They want me to be amusing. And there is nothing to laugh at in the heroine of Love on the Dole – it is all too true, that story I can tell you’ (2 March 1935, p.12).

Gracie’s response hints that she is familiar not only with the social context of the story, but also Sally’s personal experience and indeed sexual exploitation. The anonymous interviewer rather strikingly states their own view that indeed ‘It’s a pity that films will not deal with some of the most serious problems of modern life. Can’t you persuade them to do so, Miss Fields’ to which ‘Miss Gracie Fields did not answer’, at which the interviewer ‘felt rather uncomfortable’. Of course, this is still publicity for Greenwood’s film project, and to the serious nature of the story, but I think it is probably also a perfectly genuine testimony to some assumptions made not by Greenwood’s potential film team, but by Gracie’s managers, that she should not be associated with the serious or the political. The Guardian interviewer is clearly not surprised at this, but on the contrary it confirms their view of British cinema as following cheerful entertainment agendas, a view which we will meet again in relation to Greenwood’s work. Gracie Fields’ comments about the ways in which her own roles are constrained by her star persona equally highlights those expectations of British cinema as primarily ‘entertainment’ and also draws attention to Love on the Dole as a serious and political work about working-class lives, women’s lives, and poverty, something which the film industry may find it hard to take on-board.

However, progress on a film adaptation was, anyway, of course, brought to a halt by the BBFC (British Board of Film Censors) negative report on the first proposal for the film made by Gaumont British Picture Corporation and submitted to the BBFC in March 1936, when famously one of the censors, Colonel Hanna, stated numerous objections including that it was:

A very sordid story in very sordid surroundings. The language throughout is very coarse and full of swearwords, some of which are quite prohibitive. The scenes of mobs fighting the police are not shown in the stage-play, but only described, They might easily be prohibitive. Even if the book is well-reviewed and the stage-play had a successful run, I think this subject as it stands would be very undesirable as a film (BBFC Report 1936/42 held in the archives of the Reuben Library at the BFI).

The objection is not overtly to the projected film’s serious messages, but to its focus on the ‘wrong’ kind of reality and realism. Unusually, a second censor, Miss Shortt, also reported on the proposal and though her emphasis is slightly different, she is equally opposed to any film being made:

I do not consider this play suitable for production as a film. There is too much of the tragic and sordid side of poverty and a certain amount of dialogue would have to be deleted and the final scene of Sally selling herself is prohibitive (BBFC Report 1936.42).

A second film company Atlantic Film Production tried their luck with a second submission in June 1936, but since they submitted essentially the same material (the complete Cape published edition of the play) it was perhaps not surprising that Colonel Hanna said logically enough that ‘I have read the play a second time, but cannot modify the fist report in any way. I still consider it very undesirable’ (BBFC Scenario Reports).

These reports were not immediately made public in any way, though the story did gradually emerge in the press, partly through Greenwood’s own efforts, so it is not altogether surprising that the press interest in a film of Love on the Dole starring Gracie Fields did not cease at that point. Indeed, even in February 1938, the the US entertainment professionals’ magazine Variety was still in its ‘Chatter’ column reporting (presumably from insider knowledge) a Gracie Fields / Love on the Dole film possibility: ‘Negotiations still on for “Dole” as Gracie Fields pic, after author turned down $30,000’ (p.61). As Greenwood records in several press interviews he had declined very rewarding and otherwise attractive contracts to make the film because the producers or directors wanted to change the ending to a happier one, and/or make other (to him) unacceptable alterations.

In the same year Wendy Hiller, whose role as Sally Hardcastle in the Manchester Repertory production and then in the Garrick Theatre London production had brought her rapid star status, also appeared as a keen champion of a film adaptation of the novel and play, as she vigorously stated in an interview in Picturegoer on 26 February 1938 (p.13). The interview drew on Hiller’s sudden rise to stage star status and on what seemed likely shortly to be a similar level of screen stardom, and gave her plenty of space – it was a full page spread with a photograph of Hiller – to discuss her own reflections on her career and possible future. The piece is titled ‘Eliza Comes to Stay’ and is signed by the film columnist and later film publicist Dennison Thornton (1909-1977). Thornton observes that Wendy Hiller has in a period of some three years progressed from being an actor who took walk-on parts with Manchester Repertory Company to someone who ‘already has won the admiration of theatre-going thousands’ and who now ‘must earn the approval of film-going millions’.

Her career situation at this point was that, in addition to her long-running performance in the stage Love on the Dole, she had appeared already in one British film, Lancashire Luck (released 12 November 1937, directed by Henry Cass, and with a script by Greenwood’s co-writer for the stage adaptation of Love on the Dole, Ronald Gow – whom Hiller married that same year). Kinematograph Weekly thought it a sound enough picture at a certain level, but did not see it as in any way exceptional:

CINDERELLA romance with class warfare as its main dramatic prop. The entertainment never aspires above the novelettish, but its ingenuousness is both disarming and refreshing. The stars are in good form and the production work is definitely above the average. Sound quota proposition for the family and juveniles.

Story — Mrs. Lovejoy. wife of George Lovejoy. a Lancashire carpenter, wins £500 in a football pool. She decides to open a teashop in the country, and George and their two children. Betty and Joe, acquiesce. At first the enterprise. is a success, but later Lady Maydew, snobbish mother of Sir Gerald, the landowner, takes umbrage at the invasion of commercialism . . . [however, Sir Gerald and Betty fall in love and marry, so all ends happily].

Acting — George Carney and Muriel George are good as Pa and Ma Lovejoy, they are both human and humorous. Wendy is a pretty and spirited Betty [Lovejoy] . . .

Production. — There are moments when the director displays a tendency to swamp the simple plot with sugary padding, but in most cases the players reveal sufficient resource to keep what little drama there is in clear perspective. The human touch is not lacking, nor is a popular sense of humour. Atmosphere, too, is picturesque. The resources of Pinewood serve the artless entertainment in good stead.

Points of Appeal. — Friendly theme, clean romance, popular and resourceful cast, homely comedy and good production qualities (Kinematograph Weekly, 18 November 1937, p.34).

The reservations here are at least equal to the positive judgements, and I note that it is a much more wish-fulfilment based narrative about working-class life in Lancashire than Love on the Dole (as Ben Harker has suggested – see his entry under Resources for Learning About Walter Greenwood). Here a win on a bet lets a working-class family establish their own business and escape into a different life, and while class-divisions pose obstacles to their ambitions, these are fully resolved through cross-class romance. Lancashire Luck was clearly by no means for Hiller an entrance into cinema to equal her entrance onto stage as Sally Hardcastle.

Hiller expresses pre-meditated caution in the article about the shape her potential film career might take, not wanting to see her future in films only as a repetition of her success as Sally Hardcastle, and so sees this modest start in a British film as a sensible first step:

I have a horror of being typed, and I was afraid that Hollywood might type me—might try to build me up into a player who always features in the same kind of role. I had no desire to walk into filmland tagged as Wendy-Love-on-the-Dole-Hiller. Besides, the technique of the screen is so different from that of the theatre, that I felt studio work might, at that stage of my career, interfere with my development as an actress. I decided to make my acquaintance with the cinema at home rather than in a strange country. I preferred to make my debut in some small but interesting British film. That is why I appeared in Lancashire Luck which gave me my first insight into studio methods.

However, at the point of her interview with Thornton, she is about to make a more significant film appearance, still in a British-made film, but one likely to have an international impact and audience. This was Gabriel Pascal’s film of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, produced by the specially established Pascal Productions Company, and released on 6 October 1938). It was a project which aroused great public interest internationally because Shaw had after an earlier bad experiences of film adaptation refused to allow any further such versions – until he had recently changed his mind, having decided that Pascal was the ideal Shavian film-producer. Shaw had also (more or less) formed the view, having seen her in the London production of Love on the Dole, that Hiller would be an ideal Shaw actress on stage for Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion and St Joan in St Joan at the Malvern Festival in July 1936. Pascal had gone to see Hiller in Pygmalion and then cast her for the same part in his in-progress film production. For an explanation of my ‘more or less’ see another article which tells the story of why Shaw did not care for Greenwood and Gow’s play, but did admire its heroine in the hands of Wendy Hiller, and then of some differences between Shaw and Hiller when it came to her ‘Lancashire dialect’ interpretation of St Joan (see George Bernard Shaw, Wendy Hiller, and Walter Greenwood * ).

From these interview reflections about her own career at this point, Hiller was able to share her current thoughts about a possible Love on the Dole film project:

What I would really like to do after Pygmalion . . . is to appear in a film version of Love on the Dole. I have no patience with people who argue that because it deals with social conditions and problems, with slums and unemployment, it is too sordid and depressing for the cinema. After all, what about Street Scene and Dead End? Both were social. Both dealt with realities. Both were successful in England and America.

I believe producers have greatly underestimated the intelligence of the film-going public. I am convinced that that public is ready to see and to appreciate the presentation of really serious and important social problems on the screen — provided, of course, there is a good story. For this reason, I am convinced that as a film. Love on the Dole would be a sensation.

This certainly addresses perceptions of what the cinema-going public are likely to enjoy and/or tolerate, rejecting the idea that realist social problem films set in distressing environments will be too ‘sordid and depressing’ for audiences (Street Scene was directed by King Vidor, produced by Samuel Goldwyn Productions and released in the US in September 1931; Dead End was also a Goldwyn Production and was directed by William Wyler; the release date in the US was August 1937). (2) ‘Sordid’ was a word used quite often of Greenwood’s work, but I wonder if it is significant too that it was a term used three times in the BBFC’s negative reports on the 1936 proposal for a film of Love on the Dole, as we have seen above? Through her close relationships with Gow and Greenwood, Hiller might well have known of the exact language used by the censors, in which case this riposte might partly be addressed to the censors as well as the general public.

Two months later there is further reporting connected to Hiller and suggesting that definite practical plans are in place to film Love on the Dole, with Pascal as producer and Leslie Howard as director, and starring Howard himself and Wendy Hiller (presumably as Larry and Sally). These are our first potential producer and director. The film reviewer ‘Stargazer’ gives what sounds like a very well-informed view of where things are:

PASCAL BOTH SIDES ATLANTIC

Gabriel Pascal, at present producing Pygmalion at Pinewood, plans to carry the banner of English films right into the enemy camp and make two pictures here, then two in Hollywood . . . After Pygmalion there is the probability of one more picture at Pinewood, and information tends towards Wendy Hiller ‘s ambition — a film of Love on the Dole. Story conferences are taking place and Leslie Howard is keen to direct the picture (West Middlesex Gazette, 23 April, 1938, p.15)

This sounds as if the project is well-advanced: story conferences are in progress and producer, director and two leading roles are in place. However, in his subsequent interview with ‘Stargazer’ on 20 May 1938, actually carried out during the interval of a stage performance of Love on the Dole, Pascal at least sounds less than fully-committed:

Had a pleasant chat with Producer Gabriel Pascal and Leslie Howard when they went to the Windsor Repertory Theatre last week to see Love on the Dole. Both Mr. Howard and Miss Wendy Hiller, who have had the leading parts in Mr. Pascal’s production of Pygmalion at Pinewood, are keen to make a film of Love on the Dole, and in between the acts I asked Mr. Pascal what about it. He has the film executive’s non-committal smile and diplomatic manner, and he brought both into action. ‘It would have to be done artistically,’ he said. ‘I do not know whether I will make it or not.’ He agreed it had great possibilities and, pressed further, said, ‘If I could get a certain actor, I believe I would make it.’ (p.20).

‘Stargazer’ explicitly notes the ‘film executive’s non-committal smile’ (though this may be habitual) and indeed ambiguous statement of intention. What are we to make of Pascal’s comment on his much more certain conviction that the film must ‘be done artistically’? Does this imply that he is not sure the story itself is implicitly artistic, in which case what are the unstated contraries to the artistic? Perhaps the political, or social issues focus, or perhaps the grim and ‘sordid’? I suspect the certain actor is Leslie Howard, who in the same interview expressed a rather different and much more enthusiastic view of a potential film.

Leslie Howard (1893-1943) at this point was a very successful stage and film actor, and indeed a star, and had been producer for a number of films in the twenties, but had only co-directed one film, with Anthony Asquith, which was Pygmalion itself, though he was to go on to direct another three films before his life was so cruelly cut short by enemy action (for an introduction to his life and work see his Wikipedia entry https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leslie_Howard). Nevertheless, he clearly had ambitions to direct more films and indeed thought Love on the Dole would be a good place to start:

Mr. Howard had seen the original production in London and described the work as an English classic. Seeing it again, he was struck with the similarity of the work with Shakespeare, especially in the first act. He told me he would like to make a film of the play very much indeed, and agreed that there were few difficulties from a technical point of view, and it could be made quite cheaply. It would have to be done in a very real way, and very well cast.

Howard is clearly committed and his comments about Love on the Dole see it as a work not marginal to English drama, but belonging centrally to its traditions – it is Shakespearian and already an English classic and moreover it is, he feels, a viable film project, both technically and in budgetary terms. As opposed to Pascal’s concern that the story may need to be made more ‘artistic’, Howard wants to emphasise the narrative’s inherent reality and realism: he has in short different aesthetic priorities in his vision of the film.

However, in the same article ‘Stargazer’ also reported back on the rather different reactions of another film producer who was in the theatre audience that night:

I found another point of view from Mr. Victor Schertzinger, the man who made Grace Moore and produced many of her pictures, including One Night of Love . . . Mr. Schertzinger’s personal point of view was that this was not the time to use a subject like Love on the Dole. ‘That is a picture that should be made in prosperous times’, he said, ‘for it is directed at the richer folk; to make them want to help and do their bit. If I was in the position of any of these folk in the play and saw that on the screen I should want to blow my brains out. I believe that the cinema patron should find something in every picture he sees, some idea, some thought of uplift to take away with him to help him on his way’. The material was there in the play he agreed. It had tremendous possibilities, but the ray of hope was lacking. (3)

This is not quite a simple film is only for entertainment argument, but does argue that a film audiences should always be bouyed up by every film they see, and leave the cinema with better morale than when they entered, whereas a film of Love on the Dole might make some feel suicidal if they too are from a poor background. Oddly, Schertzinger sees the narrative of Love on the Dole as addressing only the rich (and not the better-off working and middle classes): those who could directly help the poor, but curiously only thinks their help should be sought when the economic situation is better. Schertzinger (1888-1941) was a multi-talented American violinist, song-writer, film-music composer and film producer and director. It seems slightly unlikely that this busy US film-maker should have been found at a stage play in the Windsor Repertory Theatre, but there he clearly was in May 1938. His Wikipedia entry records that he was a free-lance during the whole of the nineteen-thirties so perhaps he was free to travel and to explore possible British material, but he clearly did not see Love on the Dole as suitable for filming under current conditions – his career had been substantially in films which one might broadly categorise as principally entertaining (for an overview of his career see https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Schertzinger). Later, after the release of Love on the Dole, a film critic also expressed the view that the film had been released at the wrong time, but his reasoning was very different from Schertzinger’s, for he thought the wartime release context would mean audiences would not pay attention to the film’s social messages:

War Overshadows Social Lessons

It is a pity that the film Love on the Dole, which is being shown at the Odeon, Plymouth, this week, should have been made and screened in the middle of the world’s biggest war. It contains valuable social lessons which the nearer problems of the war overshadow. It would be a good film to show two or three years after the war, and so make people conscious that the war on poverty and social evils is one in which there can never be any truce. . . . The screen does not naturally publicize that Mr. Walter Greenwood . . . had a hard struggle to get his story filmed as he wrote it and not as one or two film companies thought he ought to have written it. But the author’s patience and determination have now been unrewarded (The Western Morning News, 26 August 1941, p.2)

In fact, this was not what happened with reviewers and audiences clearly noting the ways in which John Baxter’s film made links between the past of the thirties, the present of the war and the hoped for transformed post-war Britain.

On 10 November 1938 Kinematograph Weekly reported the interest not of a director but a successful producer, who had already produced some twenty-seven British pictures. This was Anthony Havelock-Allan (1904-2003) who firmly stated that next he wanted to film:

Love on the Dole with Wendy Hiller, to whom, incidentally, he gave her first film part in Lancashire Luck two years ago. ‘People have told me that Love on the Dole is too sordid and depressing for the screen’, he says ‘But they are wrong. I believe that, properly treated, it could be made the film of the year’. (p. 36).

Again, there is the wished for casting of Wendy Hiller as Sally Hardcastle, and again the description of the narrative as ‘sordid’, to which is added the further undesirable attribute of being ‘depressing’. Equally again there is the denial of these deficits and a belief that it could be an outstanding film success in Britain (for more on Havelock-Allan, though mainly on his subsequent highly successful wartime and post-war production career see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Havelock-Allan). This support for a film of Love on the Dole must surely have been expressed with a full knowledge of the BBFC’s 1936 prohibitions, suggesting that, along with many of the previous cases of support, this represents a campaign of discrete dissent from the Board’s view and a means to keep the public aware of why there had so far been no film version. I should also record an unnamed but according to Greenwood ’eminent’ film-director who proposed that Love on the Dole should be filmed as a musical – a proposal which the author clearly rejected (for fuller discussion see Love on the Dole: the Musical (1970) * ).

At long last in 1940 Kinematograph Weekly was able to report the scarcely believable news that the BBFC had very unusually changed its mind (in fact under pressure from the Ministry of Information) and accepted the possibility of a film of Love on the Dole being screened in Britain (though as it turned out this did not mean that the production team was to be given anything like a free hand – see Screenwriter Barbara K. Emary Looks Back on the Making of the 1941 Love on the Dole (1988)*). The report took the opportunity to summarise the history of the film’s non-appearance, as well as to name the intended producer and director:

Love on the Dole JOHN CORFIELD TO PRODUCE

For many years past the leading English and American companies have been bidding for the film rights of Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole, the outstanding play on social conditions, which has been seen by nearly three million people in this country alone. Efforts to acquire the film rights were defeated by the ban on the production by the BBFC. This ban has at last been lifted and the play has been acquired by John Corfield of British National Films, who plans to put it into immediate production. Walter Greenwood, the author, will write the script, and the direction has been assigned to David MacDonald. An announcement will be made shortly regarding the cast (16 May 1940, p.33).

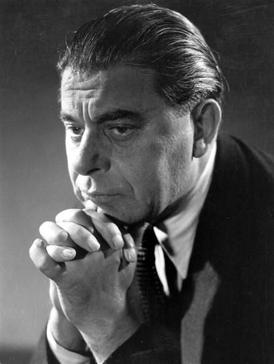

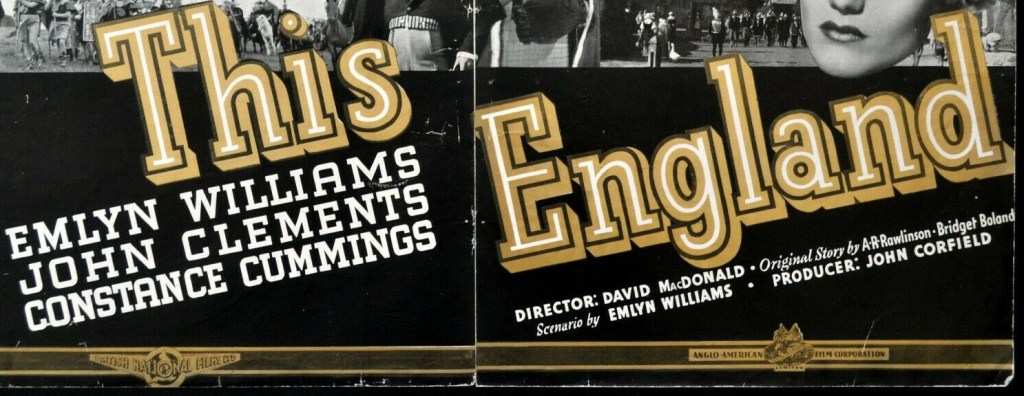

There is a shift here from earlier reports which had often identified Greenwood’s determination not to alter any essential elements in the story as a blocking factor to a contract to naming the BBFC as the main obstacle. With the acquisition of the film rights by British National Films, production became a realistic possibility and a producer and director are selected. John Corfield (1893-1953) was an experienced producer who had already been in charge of some dozen films of various genres (mostly low-budget) for British National by 1940, though he later worked on some more distinguished films, especially One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942, directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger). David MacDonald (1904-1983) had worked in Hollywood as an assistant to Cecil B. DeMille between 1932 and 1935, but had then returned to Britain where he became a director of so-called ‘quota quickies’ between 1937 and 1938. ‘Quota Quickies’ were movies produced on very low budgets to satisfy legislation designed to protect the British film industry from US competition, but which were regarded at the time as having paradoxically negative effects on the quality of British film production (however, a number of ‘quickie’ directors and producers grew into distinguished British film-makers, as a BFI article notes (see https://www.bfi.org.uk/lists/10-great-quota-quickies). Anyway, British National reassigned both Corfield and MacDonald to make This England (released on 19 July 1941) which was given greater priority as the studio’s more overt contribution to the war-effort (it followed the history of an archetypal English village’s resistance to past invaders, the Romans, the Normans, and Napoleon, as recounted to an American visitor, and was referred to by Kinematograph Weekly as a ‘national saga’, 9 January 1941, p. 73).

As a result, Love on the Dole was given to John Baxter (1896-1975) to direct and also to produce with Walter Greenwood himself as associate producer (I suspect probably in fact a condition the author had anyway laid down when signing the contract with British National in February 1940) and with Lance Comfort (1908-1966) as associate director. This might appear ‘teleological’, that is as if this was the destined and best of all possible outcomes, but nevertheless I find it difficult not to feel that this was a very good outcome, since though he had also directed ‘quota quickies’ John Baxter had an established commitment to films about working people and the very poor, including Doss House (1933, remade with a more adequate budget as The Common Touch in 1941) and the sadly lost A Real Bloke (1935). Baxter’s Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry sees his distinct interests emerging in Doss House and then recurring in most of his subsequent work:

A number of themes characteristic of the director emerged in this modest drama

about a group of dispossessed who gather one night in a local hostel: a dignified treatment of ordinary people, a strong belief in the virtues of loyalty and comradeship, and a humanistic concern and sympathy for the poor and neglected in society (by Alan Burton, published online 2013).

These concerns suggest what a good match he was as the director of Love on the Dole, which the DNB describes as his ‘masterpiece’. He had also already made a number of films featuring George Carney, the working-class actor and music-hall performer who so brilliantly played Mr Hardcastle in his film of Love on the Dole.

Baxter thus combined skills in efficiently making distinctive pictures on a low to moderate budget with his own radical artistic and social vision. An article in the Sunday Express about the film called The Common Touch (released 15 December 1941) which Baxter made immediately after Love on the Dole noted his unusually democratic and collective ways of working on a film:

In the production of a film, there’s something besides brass to be invested, namely, the brains, skill and time of the technical crew. And the return on this investment would astonish the City. I met no stars at Elstree. I met electricians, carpenters, plasterers, cameramen, in whose hands lie the reputations of stars — yes, sir, and of directors, too. Director Baxter is an unassuming man with a look of constant surprise at the superb qualities he-has discovered in ordinary human beings (by the film columnist Ernest Betts, 9 November 1941, p. 6).

This ensemble way of working with the technical crew would also have worked well with both the production crew and the actors in Love on the Dole, which is very much an ensemble piece overall. Though Deborah Kerr was to emerge from it as a star, Baxter consciously cast her because she had no pre-existing star persona. Baxter had a strong sense, expressed on several occasions, that the film must not be a star vehicle and, though she tried out for the part, he rejected the British film star and dancer Jessie Matthews on the grounds that ‘[it] was the sort of subject that would have been artistically unbalanced by big names’. The decision also accorded with the publicly stated wishes of Greenwood himself: the Star, among other papers, reported in 1941 (before the film’s general release) that ‘The film chiefs wept … the film people wanted a happy ending and Greenwood would have none of it . . . there are no stars in this film. nothing is glossed over. It is spoken of as the British Grapes of Wrath and better.’ (7 May 1941). Baxter himself said that:

The question of casting was to my mind all-important. Contrary to the view expressed by distributors and some others, I felt star names should be avoided. The play was famous in itself, and I felt concerned that if I was to secure complete identification on the part of the audience with the character in the film I must remove from their minds the picture of a particular star playing a certain part (quoted in Geoff Brown, with Tony Aldgate, The Common Touch – the Films of John Baxter, London: BFI, 1991 p.79).

John Baxter and Greenwood seem to have been in great sympathy, judging from the film they made together as well as from newspaper articles they separately wrote which referred to their film and supported distinct People’s War messages (see Walter Greenwood’s People’s War Manifesto (Sunday Mirror, 1941) and John Baxter’s article about effective film propaganda discussed early in Walter Greenwood and the Beveridge Report (1941-1945) * ). As Geoff Brown and Tony Aldgate note, the shifts in wartime politics and social sentiment played to Baxter’s already established beliefs and ways of working with film: ‘During the war, at British National, Baxter’s ‘common touch’ flourished – it chimed with the new mood of national unity and concern for the country’s social fabric’ (p.12). I think we might reasonably says that Love on the Dole fulfils Baxter’s cinema manifesto about progress which he explicitly articulated in the shooting script to the sadly lost film A Real Bloke from 1935: ‘No picture can have its right appeal unless due regard is given to how we are going to help build up a better order of things in the future’ (p.160 of the full shooting script as printed in Brown and Aldgate’s The Common Touch, BFI, 1989). This eye to the emerging potential of the future is absent from both the novel and the play of Love on the Dole, but clearly motivates the key final scene in the film, in articulation with A.V. Alexander’s textual promise about the post-war future, a grand and brave promise indeed in early 1941.

Thus finally, and despite obstacles of both censorship and film-makers’ doubts, Greenwood’s story found its entirely appropriate film producers and director, who in close collaboration, as several Kinematograph Weekly reports suggest (for example on 12 September and 7 and 21 November 1940), put much energy into finding locations, building very well-designed large sets and casting actors who could bring off each of the roles needed in this tragi-comic, sometimes despairing, but finally hopeful film narrative about the Britain of the nineteen-thirties and a hinted at contrasting Britain imagined in its post-war egalitarian transformation as a reward for national cross-class unity and courage during the Second World War. It was a true Greenwood / Baxter collaboration.

NOTES

Note 1. For Image sources see: Gabriel Pascal – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gabriel_Pascal2.jpg ; Victor Schertzinger – Wikipedia: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Victor_schertzinger.jpg; Anthony Havelock-Allan – IMDB: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0369743/; John Corfield/This England poster – The Movie Database: https://www.themoviedb.org/movie/254452-this-england/images/posters; Walter Greenwood by Howard Costner, print, 10 4/3 ins x 8 1/8 ins (273 mmx208 mm), photograph collection, NPGx1886; reproduced under a Creative Commons licence with kind permission from the National Portrait Gallery; Leslie Howard by Reginald Grenville Eves, oil on canvas, 1930s, 19 1/2 inches x 15 1/2 inches (495 x 394 mm), purchased 1952, Main Collection, NPG 3827, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence with kind permission from the National Portrait Gallery; David MacDonald from the Helensburgh Heritage Site: https://helensburgh-heritage.co.uk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=708:david-macdonald-film-director (permission to reproduce requested); Lance Comfort, from his Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Film_director_Lance_Comfort.jpg; John Baxter – production still HC07P4; Gracie Fields from her Wikipedia entry where it is stated that this is a non-copyright-marked image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gracie_Fields#/media/File:Gracie_Fields_1937.jpg ; Wendy Hiller – face of cigarette card, scanned from copy in the Author’s collection.

Note 2. For an introduction to these two films see their Wikipedia entries: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Street_Scene_(film) and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dead_End_(1937_film) .

Note 3. Night of Love had an operatic setting; it was released in the US in September 1934; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Night_of_Love and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dead_End_(1937_film)