1. Meeting Mrs Bull, ‘Uncertificated Midwife’

In the novel of Love on the Dole, the reader first meets Mrs Bull when the Good Samaritan Clothing company collector calls to collect the weekly payment for some clothing she has been provided with by his firm:

‘Call next week, lad,’ from stout Mrs Bull, the local, uncertified midwife and layer out of the dead. She sat at her kitchen table, jug and glass at hand: ‘Call next week, lad . . . Ah’ll have it for y’ when y’ call agen. Mrs Cranford’s expectin’ o’ Tuesday, an’ owld Jack Tuttle won’t last week out. Eigh, igh, ho, hum! Poooor owld Jack,’ a guzzle at the glass (Random House. Kindle Edition, 1933, p.57).

Clearly Mrs Bull is very much part of the neighbourhood of Hanky Park, and like her neighbours buys her family’s clothes on credit, and then stretches that credit as far as it will go. Like her neighbours she enjoys a drink – in this case a jug of beer (though she will happily take whisky instead whenever she can get it – perhaps that is where her clothing payment went?). Some readers might also think that her sensibilities are not much developed, given her ‘guzzling’ of her beer while remembering the deceased Jack Tuttle (though one might alternatively see this as her drinking to his memory – and/or to her fee from laying him out?). Nevertheless, she has a very necessary function in the neighbourhood, which puts her in a small ‘elite’ which is marginally better off than ordinary women (and many men). She is, as the passage states, ‘the local, uncertified midwife and layer out of the dead’. These functions are generally in modern Britain, anytime after 1920 and certainly after 1945 at least, split across two vocations: midwife and undertaker, but this introduction to Mrs Bull certainly implies that they are combined in her person. She introduces the new citizens of Hanky Park into this life, and she prepares departing citizens for exit from it, in both cases for a small(ish) fee from which she makes her living. This gives her an expectation (and perhaps too the Good Samaritan collector) that she will be able to pay up next week, for one birth and one death are due. In the 1937 short story ‘Joes Goes Home’ (published in The Cleft Stick collection, with illustrations by Arthur Wragg), we meet her under slightly different circumstances preparing the frail and elderly Blind Joe Riley, who has spent a lifetime as a ‘knocker-up’, waking working families who cannot afford alarm-clocks (that is to say every family in Hanky Park), to be taken to the infirmary by an ambulance. The description of her function is similar, though it makes her sound as if she sometimes may work charitably:

Inside the house, stout Mrs Bull, the neighbourhood’s uncertificated midwife and often unpaid nurse, was washing Joe’s hands and face. ‘There you are, old lad’, she said, when she had finished. ‘Clean as a pin and fresh as a daisy’ (p.107).

One difference is that her role as layer out of the dead is not mentioned – and perhaps it would be tactless since everyone among the neighbours who are at their doors for the exciting event of an ambulance in the street are certain that ‘it’s the finish of the old lad’. Nevertheless Mrs Bull retains her association with death at the end of the story when Joe has been collected, observing ‘seventy-five’s not a bad age. And that’s how we’ll all go, one of these days’ (p.109). She, as well as the neighbours, equate going to the infirmary in old age with certain death.

2. Birth and Death; Handywomen and Midwives

In this article I will look at all the forms birth and death take in Hanky Park, across both Greenwood’s novel and his short story collection set there. My title, of course, refers to the notably successful BBC television series Call the Midwife (2012 – to the present), which celebrated and recreated some aspects of the history of midwives and of women in the East End of London in the nineteen-fifties and nineteen-sixties (it was also a large success when broadcast by the admirable PBS – Public Broadcasting Service – in the US). TV reviewers generally thought the series gripping, grimly realistic and thoroughly engaged with the situation of working-class women before easily available contraception, and when birth still more often took place at home rather than in hospitals. Though Call the Midwife concerns midwives who work for an Anglican foundation and is set in a poor part of London, it shows considerable continuity with Greenwood’s writing about midwives and birth in Salford (though with death added in his case). It therefore seems a highly relevant rather than incidental reference: this article ‘Call the Handywoman’ takes the history of birth back into the nineteen-twenties and thirties when, whether officially or not, midwives and handywomen still co-existed for a time (for a useful introduction to Call the Midwife, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Call_the_Midwife).

Another Hanky Park midwife, Mrs Haddock, also appears in a different short story in The Cleft Stick. We will return to her later, but for the moment let us explore further the portrayal of Mrs Bull. It seems important to clarify the term used twice of her so far: ‘uncertificated midwife’ and also to explain the term used in the title of this article, ‘handywoman’. There are several book-length studies of the history of midwifery which can help greatly here, for in fact the whole history of midwifery is bound up with the term ‘handywoman’, until that term was (if only gradually) rendered redundant during the first four decades of the twentieth century. (1) However, in the first instance my first and best resort for definitions is always OED (Oxford English Dictionary). ‘Midwife’ is defined as originally simply a ‘woman who assists in childbirth’, with an etymology simply derived from ‘mid-wife’ – ‘with a wife or woman’, and a first recorded usage in 1300. OED surprisingly does not have an entry for the word ‘handywoman’, but does list the clearly related ‘handwoman’ with ‘the rare and historical sense of midwife’ (sense 2), and gives the first usage as 1637. It also lists a usage from 2000 in which the distinction we will next explore between the modern ‘midwife’ and ‘hand[y]woman’ is deeply embedded: ‘the phasing out of the unqualified handwoman by the Midwives Act of 1902’. I think this OED entry (precisely because it does not trace the usage of the exact and more commonly-used term ‘handywoman’, which I think would be more extensive in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that that for ‘handwoman’) underestimates the word’s significance for women’s history, and especially working-class women’s history, in Britain, as our more specialised sources evidence. All these studies are useful but I will draw mainly on the highly engaging, original and readable book below.

Nicky Leap and Billie Hunter’s The Midwife’s Tale – an Oral History from Handywoman to Professional Midwife (Scarlet Press, London, 1993) opens with a summary of the crucial context:

In the 1990s in Britain, midwifery is a profession open to women of all social classes and backgrounds, but this has not always been the case. In the early part of this century the profession was restricted to women who could afford the training , in terms of both money and opportunity. A successful campaign to professionalise midwifery was in operation, spearheaded by socially influential, aristocratic and middle-class women whose aim was to build a new profession for women and eradicate the practice of the working-class lay midwife – the ‘handywoman’ (Introduction, p.ix).

While this movement was a key social reform aimed at professionalising practices which could mean the difference between life and death or permanent disability for women and infants, it also had a clear class dimension in which trained midwifes were seen as categorically opposed to the handywomen who had cared for working women for hundreds of years. Greenwood never uses the word ‘handywoman’, but the descriptions of Mrs Bull make it very clear that this is what she is. Here is Leap and Hunter’s definition of the role of the handywoman and her status within her community:

Before the First World War and, in some areas, until the mid-1930s, the majority of working-class women in Britain were attended in childbirth not by a professional but by a local woman. She was likely to be an older woman, a respected member of the community. Her role would often include looking after the sick and dying and laying out the dead [however] . . . the main focus of the handywoman’s work was that of midwifery (p.1).

Attendance at childbirth, sometimes nursing the sick, and laying out the dead are exactly the activities linked to Mrs Bull by Greenwood. We might also note that she is indeed respected and a source of wisdom and medical knowledge (including mental health issues) for women in her neighbourhood, passed on in a homely way. In Love on the Dole she obliquely advises Helen after her baby is born that there is such a thing as family planning, and tells Mrs Hardcastle that life in Hanky Park can make some people suicidal after Sally has resorted to desperate measures to escape. In the short story ‘The Cleft Stick’, she tells Mrs Cranford, who has three children and an unhelpful and idle husband, that there is something called ‘the change of life’ (the menopause) which is what is making her feel so dreadful, but that it will pass, and also at least means she will have no more children.

What makes Mrs Bull an ‘uncertificated midwife’ is precisely that drive from above to redefine ‘midwife’ as trained, professional and approved and ‘handywoman’ as the contrary: untrained, amateur, unregulated and liable to be hazardous for women’s and infant health and survival, particularly because of a supposed lack of up-to-date medical knowledge about hygiene and infection. This distinction emerged in the last decades of the nineteenth century, particularly through a well-connected pressure group called the Midwives Institute, established in 1881. By 1902, having worked carefully with ‘social reformers, politicians and the medical profession’, partly to make it clear to mainly male doctors that midwives would deal only with relatively uncomplicated births, and thus not encroach on their work or fees, the Institute helped bring into being the First Midwives Act (Leap and Hunter, p.2). This controlled the right to practice as a midwife in England by establishing the Central Midwives Board:

The Board formulated restrictive practice requirements, a powerful supervisory apparatus and a plenary system [an agreement that all policy be approved by the whole Board], all of which were successfully designed to make it impossible for working-class midwives to continue in the practice long-term. All midwives who had a recognised qualification from the London Obstetrical Society or from certain lying-in hospitals could enrol on the register of qualified midwives . . . All other women who wanted to practise as midwives had to pass an examination in competence before a certificate could be issued to them. The cost of training was far beyond the means of most working-class women, and the language used in the examination, such as medical Latin, made it impossible for all but the highly educated to pass (Leap and Hunter p.4).

This, of course, is the certificate which Mrs Bull does not have (and nor does it indeed seem likely she could under these circumstances have any hope of acquiring it). Given that Greenwood’s references to her were published thirty-one and thirty-six years after the 1902 Act was passed, it might seem odd that she is still able to act as a handywoman without suffering legal consequences:

Under the Midwives Act of 1902, after 1910 no person could ‘habitually and for gain’ attend a woman in childbirth except under the direction of a doctor, unless she was a certified midwife (Leap and Hunter, p.7).

However, the wording of the account of the 1902 Act tells us that despite the categorical approval only of certificated midwives, there were practical issues in making this become reality overnight. There simply were not enough approved midwives to replace all those who had been practising that vocation in one way or another, and actually some doctors continued to work with handywomen they knew and trusted for this very reason, thus somewhat unavoidably undermining the ideal core intentions of the 1902 Act. Indeed, a procedure was developed to accept for a time-limited period women who had experience of midwifery but not any academic background:

Women who had been in practice for a least one year and who could show proof of good character by producing a reference from a clergyman, could also apply [for registration]. They were known as bona fides and were accepted by the authorities as a stop-gap measure in order to cover a temporary shortage of midwives (Leap and Hunter, p.4).

This however was not intended to let worthy handywomen into the profession – on the contrary – but may help us explain certain aspects of Greenwood’s other midwife, Mrs Haddock, in due course. It is clear that the 1902 Act did not succeed in one stroke for there were further Midwifery Acts building on it, and often restating central criteria, of which we might especially note the Third Midwives Act of 1926 which stipulated that ‘uncertified women attending a birth’ must satisfy a court that ‘it was a case of sudden or urgent necessity’ (Leap and Hunter p.7 and p. 200). Nevertheless, handywomen still seemed to be attending births in some capacity (perhaps they found themselves surprisingly often nearby to cases of sudden and urgent necessity?) into the nineteen-thirties, which is clearly the case for Mrs Bull. However, in 1937 Greenwood had a very public spat with a well-known champion of professional midwifery about whether handywomen could really still be found in Salford at that date. We will return to this dispute about fiction and fact towards the end of the article.

One profound, though by no means the only objection of the Institute of Midwives to handywomen, was indeed that other function of laying out the dead. It was felt (with some reason) that ‘since she [the handywoman] layed out the dead, there was a potentially high risk of her transmitting infection to childbearing women’ (Leap and Hunter p.10). Indeed, the Central Midwives Board absolutely forbade midwives to lay out bodies (though there is research arguing that ‘handwashing’ rituals were embedded in the habits of handywomen which actually mitigated this risk). (2) I speculate that genuine clinical issues apart there may too have been an anthropological element in this central Midwives Board prohibition – a newer cultural sense that birth and death should be separated between different practitioners as absolute opposites. Whatever the scientific or spiritual underpinnings, Mrs Bull was clearly in breach of this injunction and still following older precepts during the nineteen-thirties. Of course, one issue here was economic, since ‘laying in’ and ‘laying out’ between them were more likely to bring in a sufficient living income than either as single specialisms. This economic logic may also be why, as with other historical handywomen, Mrs Bull will sometimes take on some nursing of the sick and even some childcare. I should emphasise that Leap and Hunter are not arguing from their oral history interviews that the professionalisation of midwifery was a bad thing, on the contrary, but that any assumption that all handywoman lacked knowledge is a simplification. Indeed, they produce much oral-history testimony that many handywomen were highly valued in their communities and that they often (though not invariably) possessed considerable skill and knowledge about child-birth and maternity-care (see Leap and Hunter, chapter 2, ‘Handywomen: the woman you called for’).

3. Mrs Bull’s Handywoman Business in Hanky Park

Love on the Dole makes the continuing practice of Mrs Bull into the twenties and thirties very clear since its main events, as we can see from Harry’s seven-year apprenticeship and the introduction of the Means Test after he has completed this and been laid off, take place between 1924 and 1931. During the course of the story we learn that Mrs Bull has laid out Jack Tuttle, because of the ‘dialogue’ she initiates with him in the course of the séance and we also learn that her peers expect her to lay them out too since when Mrs Dorbel fantasises about winning the Irish Sweepstake, Mrs Bull says: ‘Aye, an’ Ah’d be layin’ y’ out in a month, drunk t’ death, fur coat an’ all.’ (p.100). Mrs Bull ends the scene and exits the house with a similar assertion of reality, saying Mrs Dorbell does not need her fortune told since:

‘Ah can tell it, lass, an’ Ah’m no fortune teller. Tha’ll keep on drawin’ thy owld age pension and then tha’ll dee. Ah’ll lay thee out an’ parish’ll bury y’.’ She waddled away, chuckling (p.102).

Shortly afterwards at another gathering of the older women at Mrs Nattle’s house to share a convivial glass of gin (at threepence to the host per measure), Mrs Bull laments the current state of business, making clear that her handiness still spans the two traditional realms of birth and death:

‘Yaa – Ah don’t know what’s comin’ o’er folk these days. Ah remember time when ne’er a day hardly passed without there was a confinement or a layin’ out to be done,’ bitterly: ‘Young ’uns ain’t havin’ childer as they should. An’ them as die’re bein’ laid out by them as they belong to which weren’t considered respectable in th’owld days. When Ah was a gel a ’ooman wasn’t a ’ooman till she’d bin i’ childbed ten times not countin’ miscarriages. Aaach! How d’ they expect a body t’ mek a livin’ when childer goin’ t’ school know more about things than we did arter we’d bin married ’ears?’ Nobody had an explanation to offer (pp. 106-7).

How things ain’t what they used to be is, of course, often an enjoyable conversation topic so that may be partly what motivates this exchange between these older women running their small ‘businesses’. Thus Mrs Dorbel asserts during the conversation that ‘Things ain’t bin same since genklefolk left th’owld Road,’ while Mrs Jike for her part thinks that ‘The world’s ne’er been the sime since the old Queen died’ (both from p.107). Nevertheless, Mrs Bull suggests here that for herself there are currently some specific and significant changes in the market for handywomen (though rivalry from certified midwives and the new rigour of the law are two changes she makes no reference to). She states that young people are having fewer children than they used to, or even than is ‘natural’, and puts this down to increased knowledge at an earlier age. Though very much implicit this can only be a reference to knowledge about birth control or family planning, the terms used to refer at this period to what was sometimes also called ‘family limitation’. (3) The reference to changed conditions in laying out is much briefer, and though causation remains inexplicit we could reasonably guess that respectable or not, families simply cannot afford even the handywoman’s fee under current Depressed conditions, though this would normally out of mutual interest be calculated to be within a working-family’s possible budget.

This statement from Mrs Bull makes the functions in her occupation very clear, but her (commercial) sentiments here seem slightly at odds with her general character in the novel (and indeed as developed in the play and film). In the main, Mrs Bull seems to earn the respect she is given for both her skills and her wisdom about health matters and her humane concern for others. As I have already mentioned, she discreetly suggests to Helen that one child may be enough, and she certainly recognises the suffering of Mrs Cranford who has had to have children she can neither afford nor bring up properly. In fact this statement is the only time when she seems to put her own ability to make money above humane sympathy for working women and men. It may be that the shift from sympathy to profit is motivated by needing to be part of her peer-group – a group where the profit motive always ranks above fellow-feeling, at least in the cases of Mrs Dorbel and Mrs Nattle – Mrs Jikes seems more fun-loving than grasping, and as she herself says: ‘The Lord loves a cheerful soul’ (p.162). Mrs Nattle sticks to business logic and challenges Mrs Bull’s analysis of her business prospects by suggesting that actually the Depression will do some good to handywomen since the anxiety will increase mortality sharply:

‘Well, there’s nowt like worry for poppin’ folk off. An’ that’ll be no ill wind for thee, chargin’ like y’ do for layin’ folk out. Wot Ah’ve seen o’ some folk round about here – worritin’ their guts out like damn fools – What Ah’ve seen of ’em there’ll be plenty o’ work for you, soon enough’ (pp.162-3).

However, just as in The Cleft Stick story about Joe Riley going to the infirmary, where Mrs Bull seems to nurse him for free out of charity, so also in Love on the Dole Mrs Bull confesses that she is giving another poor neighbour considerable help without any payment:

‘Ah, well, Ah must be off, Sal. Ah’ve a rare pile o’ ironin’ t’ do t’ neet. Poor soul wi’ a tribe o’ kids as lives in next street’s bin confined agen. They’d ha’ charged her ten bob for t’ washin’ if she’d ha’ sent it t’ t’ laundry. Couldn’t even afford t’ pay me for tendin’ her i’ childbed, an’ him workin’, too! Blimey, wot a life, Sal, wot a life’ (p.216).

Not only does Mrs Bull here not charge for her skills in attending at childbirth, but even takes on additional domestic labour because she knows the mother cannot do it herself nor afford to pay someone else to do it. Her closing comment in the above quotation also suggests someone who has reflected carefully on the situation of women in Hanky Park in general.

So too does her commentary about Ned Narkey’s long-suffering wife Kate Malloy in the Cleft Stick story, ‘A Son of Mars’. In Love on the Dole, we witness Sally trying to shame Narkey into marrying Kate whom he has got pregnant (p.166). In this story we see into Narkey and Kate’s married life:

‘It’s a fair shame, it is,’ said Mrs Bull. ‘That poor wife of Narkey’s is always in the family way. Expectin’ this very minute, she is. I thought she’d have bin confined afore this, bein’ as she had a shock when the chile died [one of their other infants]. She nodded towards Ned’s family running about the street. ‘And just look at them that’s livin’. Something ailin’ all of ’em. Not that she’s to blame: what can she do with a big hulkin’ brute like him? Naow! He’s a bad ‘un, is Ned’ (pp.132-3).

Mrs Bull’s view is that Ned takes no responsibility for his actions or children, and indeed forces himself on Kate despite the size of the family and his now unemployed status. Thus poverty is reproduced. In fact, Ned’s only interest in the child’s death is in claiming the insurance money, which he does in preference to going to the funeral. No wonder Mrs Bull is appalled, despite her wide experience.

Another case advised on by Mrs Bull in the novel includes a (free) word of warning to Sally about Larry’s health: though he is a ‘gradely lad’, he is not of the strongest and because of his cough it would be better if he ‘luked to his health more’ (p.164). It is a topic Mrs Bull returns to, as Sally later recalls. Mrs Bull’s view is that even if a doctor’s fee has to be paid Larry is ill enough to need medical care beyond her level of skills, and she also feels she knows how men respond to illness, by ignoring it until too late: ‘That there cough ain’t no ordinary cough an’ calls for doctor if Ah know owt about it. You see as he guz, lass. Men allus neglec’ ’emselves. Allus’ (p.191). Though the film makes nothing of this, where she does not feature at all in the scene, Mrs Bull is fetched by Harry when Helen goes into labour at Mrs Dorbell’s house and attends at once and willingly: ‘Aye, lad, Ah’ll hurry’ (p.235). Mrs Bull’s attendance is clearly always a public or perhaps better community spectacle too, involving all women neighbours:

In a moment most of the street was acquainted with the news, and in another moment a group of women had assembled in and about the front door chatting concerning the peculiarities of their confinements (p.237).

‘Confinement’ is a key, potentially hazardous and shared experience for the women of Hanky Park. We however have no record in the novel of whether Mrs Bull charges the penniless Helen and Harry for her work as handywoman, but I suspect not.

A little later we also witness Mrs Bull’s efforts to counsel her neighbour Mrs Cranford who is constantly harassed by an idle and absent husband, too many children, an insufficiency of money, and endless anxiety. Sally is present as Mrs Bull gives her advice and Mrs Cranford tells the younger woman directly to avoid marriage if she can, since the inevitable consequence is the same as hers: ‘Worritin’ me guts out tryin’ t’ mek ends meet, an’ a tribe o’ kids t’ bring up on what he and me can earn’(p.244). Mrs Cranford’s experience of marriage in poverty is:

Stichin’ till Ah’m blind. Then when there ain’t no work i’ that line Ah’m washin’ from Monday till Thursday an’ kids t’ be tuk t’ t’ clinic. Aw, Gord! Ah wish Ah wus dead an’ out o’ t’ way …’ (p.244).

Mrs Bull tries to give some cheering counsel in the novel though it is more about enduring than escaping:

‘Naterally dismal, Mrs Cranford,’ said Mrs Bull: ‘That’s allus up wi’ you. Y’ jest naterally dismal. Y’ve a lot t’ learn, lass, a lot t’ learn. Ne’er in all my life have Ah seen anybody as tuk things so serious. Allus y’ want’s a nip o’ Scotch now an’ agen. Mek y’ forget y’ troubles’ (p.245).

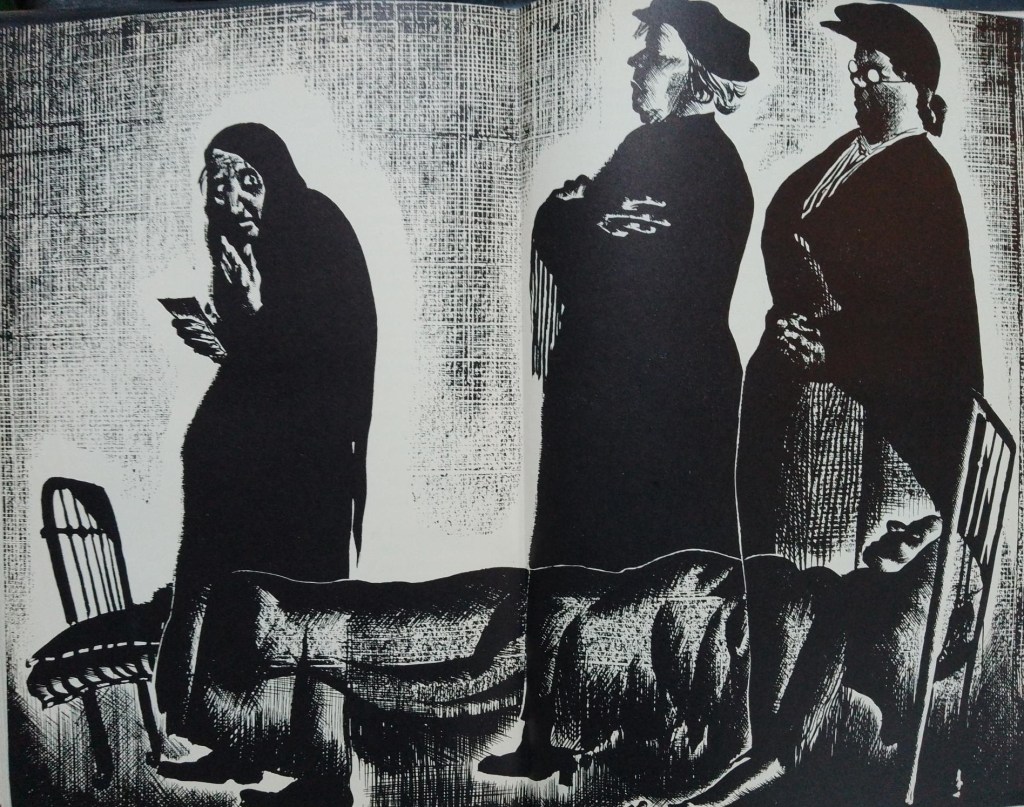

(Mrs Bull sometimes prescribes gin, and sometimes whisky – it depends on the case). Mrs Bull does add that when the children are grown up they’ll bring home their wages, but Mrs Cranford dismally protests that they will simply repeat her mistakes, marry and begin the cycle of poverty all over again. This material is a close reworking of a short story (one of Greenwood’s best in my view) which he wrote while unemployed between 1928 and 1932. Originally titled ‘Mr Cranford’s Wife’ he retitled it ‘The Cleft Stick’ for its first publication in 1937 in his and Arthur Wragg’s short story collection, The Cleft Stick or ‘it’s the same the whole world over’ (Selwyn & Blount, London, pp.59-70). There are some differences between the two versions of which the first is that in the original story Mrs Cranford feels so wretched that she tries to commit suicide – but does not have a penny for the gas meter.

In the short story Mrs Bull arrives as something of a saviour and gives some precise medical advice to Mrs Cranford, advising her that she feels so miserable because she is suffering from the menopause (‘the change o’ life’) and that this will pass AND mean that she will have no further children. This is all news to Mrs Cranford who has never heard before about this universal female life-experience. I speculate that the omission of both suicidal feelings and the menopause in the novel version of the material was because Greenwood felt it was venturing onto ‘unmentionable’ and therefore unpublishable ground, ridiculous as that seems to twenty-first century ears – though it is only in the last five years that open discussion of the impact of the menopause has been accepted in (some?) British workplaces (for a fuller discussion of the ‘Cleft Stick’ story and its Arthur Wragg illustration see Word and Image in Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg’s The Cleft Stick (1937) * ). Mrs Bull also draws on her own knowledge of serious mental distress and its strongly material causes in Hanky Park when she tries to persuade Mrs Hardcastle that Sally will after Larry’s death be better off out of Hanky Park even if she does have to become Sam Grundy’s mistress (though I have always had some difficulty in wholly accepting the logic of this):

Let me tell y’ this: if she’d ’ad much more of it Ah’m certain that she’d ha’ done wot yon poor soul i’ next street did yesterday … cut his throat an’ jumped out o’ bedroom window when he got letter from Guardians sayin’ he’d got t’ give five bob a week to his wife’s people wot come under Means Test. Five bob a week, poor soul, an’ he couldn’t keep his own, proper. Yes, Ah could see it i’ your Sal’s face all right; moonin’ about like a lost soul; sittin’, night after night on this here couch gawpin’ at nowt.… It all come out night as y’ ’usbant landed her one, now didn’t it, now? Wot she said was only wot she’d bin thinkin’ e’er sin’ Larry kicked bucket,’ a deep breath: ‘Aye, she’s had a bellyful all right. An’ she’d ha’ gone melancholy mad if it’d ha’ lasted much longer (pp.253-4).

Mrs Bull makes it clear that she recognises from experience the symptoms of a breakdown and also implicitly asserts, perhaps against some middle-class readers’ expectations, that working people cannot get used to anything which happens, but absolutely have their breaking points as people of more privileged classes also do.

Mrs Bull also escorts Sally to the safety of her house after her father has hit her as she confesses to her ‘bargain’ with Sam Grundy. The handywoman tells Mr Hardcastle that he is being a fool in committing this act of domestic violence, and he does indeed come the next day to Mrs Bull’s house to at least apologise to Sally. Next Mrs Bull continues her good work by helping Helen after the birth of her daughter. Sally has helped her brother Harry and his new wife to rent a house and the couple need to furnish the completely bare rooms with hire-purchase furniture. Mrs Bull agrees to do another thing sometimes undertaken by handywomen, some childcare, and also gives some further advice for a better future:

Y’see. Ah’m startin’ work agen soon so we’ll be able t’ pay money off quicker. An’ Ah’ll want somebody t’ luk after baby.… Y’ve bin so good.… Ah wondered, like.… Ah’d pay y’ if y’d see to her durin’ day for me.… Would …?’ ‘Aye, lass, she’ll be all right wi’ me.’ She gazed at Helen, steadfastly, ‘An’ if y’ tek my advice, lass, y’ll mek this one y’ last. One’s too many sometimes where workin’ folk’re concerned. ’Tain’t fair t’ you an’ ’tain’t fair t’ t’ child. Luk at Mrs Cranford. One reg’lar every year, an’ half of ’em dead. An’ Kate Narkey shapin’ same way. Yah, them two fellers ought t’ be casterated’ (p.254).

Of course, Helen is returning very early to work without any option because the couple need the money to make any kind of life, but at least Mrs Bull agrees very readily to provide trustworthy daytime childcare (for a presumably small fee). Her next advice though fairly discrete to begin with is clearly about family planning or birth control, and its very material benefits for working-women, with Mrs Cranford and Kate Narkey as examples of what happens to women whose husbands take no care to live within their means when it comes to children. I am certain that Mrs Bull knows there are other possible methods of birth control than the grimly comic malapropistic justice she prescribes for Jack Cranford and Ned Narkey. However, I am not certain that Helen is as knowledgeable – she finds the merely implicit reference to family planning so embarrassing that she turns the subject, and thus loses a possible learning opportunity:

Helen shifted uncomfortably, glanced at the clock then said, in genuine alarm: ‘Ooo, luk at time . . . Harry’s tea’ll ne’er be ready when he comes,’ smiling at her mother-in-law and Mrs Bull: ‘Ah’ll have t’ be goin’ (p.254).

Shortly after this the novel ends with a near repetition of its opening, suggesting that, as Mrs Cranford fears, the repetition of desperate lives and the reproduction of poverty is likely to be the fate of most in Hanky Park. Though Mrs Bull in the stage-play mostly looks like just one of the chorus of three elderly women, there are points in novel, play and film where she stands out as distinct from her peers. The first Greenwood critic to really appreciate the full importance of Mrs Bull was Jack Windle, who among other things in his wide-ranging 2011 article about how to read Love on the Dole in terms of its authentic working-class context, argued that Mrs Bull was an alternative kind of political leader in Hanky Park to Larry Meath, supplementing his partly theoretical (and male-centred?) politics with a down-to-earth practical set of tactics to try to make life more tolerable for working-class women and men in the here and now rather than the future. Windle points out that in her advice to Helen:

Mrs Bull . . . echoes the Women’s Co-operative Guild and the Workers’ Birth Control Group who campaigned for smaller working-class families and better conditions for women. With this attack on the large family conventional in working-class communities, Mrs Bull completes the novel’s sustained and devastating attack on the institution of marriage (p.44 and endnote 39). (‘ “What Life Means at the Bottom” – Love on the Dole and its Reception since the 1930s, Literature & History, volume 20, Issue 2 – though sadly this is not an open access journal – https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.7227/LH.20.2.3 ).

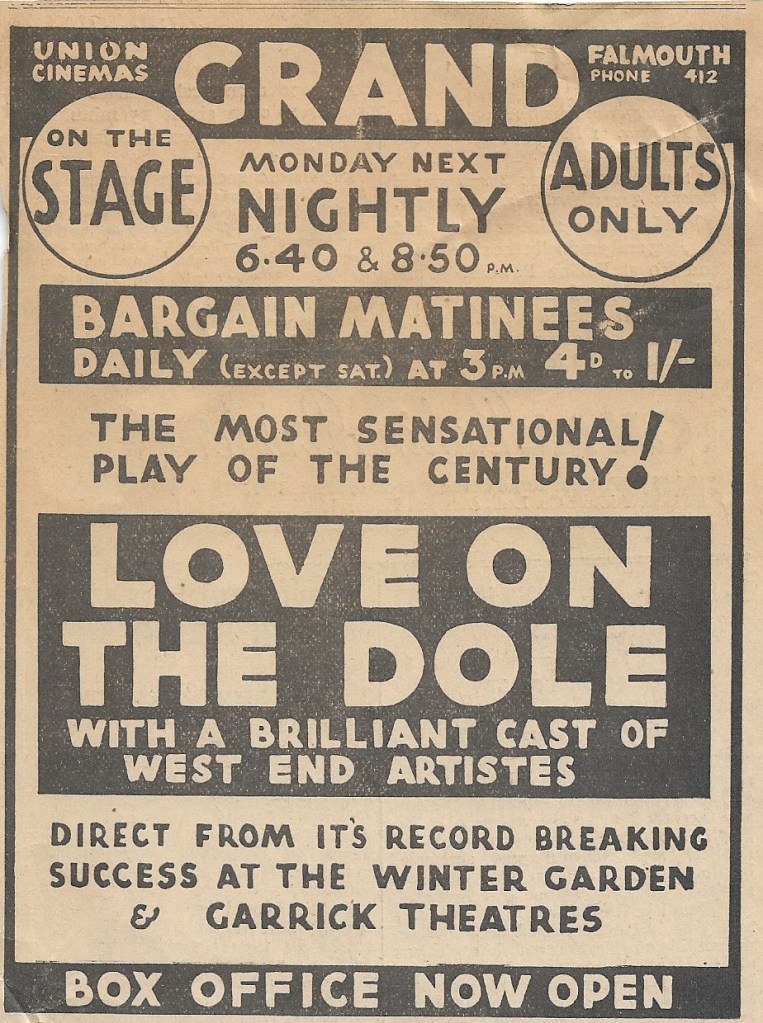

Mrs Bull’s role as handywoman is clearest in the novel of Love on the Dole, no doubt because of very real concerns about what topics could safely be mentioned in the theatre and in the cinema. However, though she is less explicitly identified as a handywoman in play-text or film-text, those who have ears can hear from key speeches by Mrs Bull in the play that she is indeed still the woman who is called to births and deaths (especially in versions of the novel speeches quoted above from pages 106-7 and 253-4, which occur in the Cape play edition on pages 42 and 115). The character description in the Samuel French editions (British and US) simply says of Mrs Bull that she is ‘a large woman’, with no mention of her skills or occupation. Nevertheless, one of the two British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) readers certainly picked up the fairly implicit reference to family planning by Mrs Bull in the play (p.42 of the Cape edition, its version of her speech in the novel on pp.106-7). Miss Shortt wrote in her report without naming the unspeakable topic of birth control that this speech would have to be cut from any film version because ‘it would be impossible according to our standards’ (BBFC Scenario notes, 1936, p. 42a, held in the BFI Ben Reuben Library; discussed in my book pp. 75-6).

In fact, the 1941 film kept a (reduced) version of this speech and indeed at least four other veiled references to related play material about sex, birth and ignorance of birth control, as well as introducing a completely new and quite risque reference to Mr and Mrs Cranford and their numerous children. This first allusion comes in dialogue between Mrs Nattle and Mrs Bull in the scene set early in the film in the pawnbrokers: https://youtube.com/clip/Ugkxb6J27oMw-fTl84zqOdl1Ya6mYDIa1lGO?si=_0nuY17VcdNH2_Ri (20 seconds). Though the comment by Mrs Bull that Satan finds work for idle hands has a comic aspect, it also, in combination with Mrs Nattle’s observation that Mrs Cranford is ‘expecting her seventh’ and Mrs Dorbell’s comment that Jack Cranford is only working three days a week, offers a severe critique of a system of social/family economy which leads to large families with no prospect of their being properly fed, housed or looked after. This is in line with other references to related themes by Mrs Bull and others kept in reduced form from the play: at 14 minutes in Mrs Bull gives her speech about the reduction of both confinements and layings-out (though the reference to young people knowing too much has gone), at 15 minutes 21 seconds in the chorus of older women talk about how Harry Hardcastle’s troubles will start as soon as he begins courting, at 1 hour 23 minutes in Helen laments not knowing that pregnancy would likely result from pre-marital sex (though she uses none of these words her meaning is very clear and its statement in the film is daring), and a minute later Mrs Dorbell comments on the results of ‘sitting out’ with men on Dawney Hill (a patch of green land in Hanky Park), while Mrs Jike tells Mrs Bull that Helen’s confinement will mean a job for her. Though these are all allusive references, they are unexpectedly plain enough to any (informed?) adult, despite the BBFC’s generally prohibitive attitude to even the hint of such contents. The extraordinary intervention of the Ministry of Information in the judgements of the BBFC in 1940 might have given the film a certain special status, but nevertheless it certainly was not freed from all the usual protocols exercised by the BBFC, as the memories of one of the screenwriters, Barbara K. Emary confirms – she recalls a process of ongoing and difficult negotiation with the censors by the director John Baxter throughout the production period (see Screenwriter Barbara K. Emary Looks Back on the Making of the 1941 Love on the Dole (1988)*). I am more inclined therefore to regard these allusions as things the film got away with rather than things it was specially permitted. One might also bear in mind that while for some picture-goers the film was their first meeting with Love on the Dole, for many others it was not, since the novel and even more so the play had had large audiences. Attentive readers might well be perfectly well-aware of the systematic references across the three texts to the effects of unplanned birth in conditions of poverty and unemployment, and to Mrs Bull’s quiet advice. Adverts for both play and film warned of (or promised?) adult content, which surely included this kind of material.

Our tracing of Mrs Bull’s activities in the novel, and their echoes in play and film, does indeed suggest that she is something of a working-class heroine, helping her neighbours when they are in most need, as well as making a living from her diverse caring skills. I note that no-one ever complains in novel or play or short stories or film that her skills are in any ways deficient, despite that lack of certificate.

4. Meeting Mrs Haddock, ‘Certificated Midwife’

Mrs Haddock is a very different character from Mrs Bull. She figures in The Cleft Stick short story ‘The Practised Hand’ (Selwyn & Blount, 1937, pp. 194-211), and her status as a certificated midwife is stressed as soon as she is introduced:

[She was] wearing a striped frock reaching to her ankles, and, over this frock, a white, starched apron very clean . . . Her home was as tidy as herself. Her husband was secure in his job as a mill overlooker and Mrs Haddock augmented his wages by attending, in the capacity of usher, to the entrances to this world of all the Salfordians in the immediate vicinity of her home. A certificate testifying her capacity in this profession hung upon the wall and a brass plate, bolted to the front door, announced her trade to the prolific world (p.201).

Clearly, her qualified status matters to Mrs Haddock and is something she wants to project both in the private sphere and in her interface with the ‘trade to the prolific world’. Two unusual-seeming word-choices rather stand out here: midwifery is not usually described as a ‘trade’, and the unusual adjective for the world, ‘prolific’, is used to signal how the more births in Hanky Park the better for that ‘trade’. We get then a rather mixed opening view of Mrs Haddock: status and respectability seem to be priorities for her, but so too are her business interests.

When Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle (neither of whom are that strong on tidiness or respectability) knock on Mrs Haddock’s door to ask for her advice, she asserts her higher status by taking charge but also by continuing to drink her tea, without of course offering her prospective clients any. They are not, of course, themselves in the market for midwifery, being past child-bearing age, but Mrs Haddock assisted Mrs Nattle when her husband was dying. Of course, as we know from earlier material in this article, midwives should have no business with the dying or dead, that being in the domain only of the more versatile and disapproved handywoman. However, as it turns out, Mrs Haddock’s commerce with the dead goes way beyond anything usually practised by a handywoman. Mrs Nattle’s husband was dying slowly and she had contacted Mrs Haddock to see if she could ‘help’ him, which for a fee she was able to do. This is a kind of ‘assisted dying’, but without the preamble of any long-debated legislation, ethical review, or safeguards (still of course at present being further considered by the Westminster Parliament). Mrs Dorbell’s case is not that of a close relative but of her long-term lodger Ben, on whom she has taken out a life-insurance policy. He too though is ‘lingering’:

He’s not no better: no, nor likely to be, either. He’s a-dyin’ . . . been a-dying for fourteen weeks now, but he just won’t die. Proper cont’ary . . . It isn’t as though I want him to go; but I think he knows I’m waitin’ and he’s just tryin’ to be awk’ard . . . Ay Ben, lad, if you only knew the struggle I’ve had this last twelve years to keep you in benefit! Denied myself, I have for to do it (p.197).

This is, of course brilliantly satirical: Mrs Dorbell has done everything she can to sacrifice herself for Ben – keeping him in what sounds good for him, ‘benefit’, except of course that in this case that is an insurance term indicating the sum paid to his insurer, Mrs Dorbell, upon his death. That sum is carefully specified (and keenly anticipated) by Mrs Dorbell: it is twelve pounds ten shillings, based on her paying a weekly tuppenny premium for twelve years. One might reasonably say that she has invested all her spare change in his death, and is eager now to realise the ‘benefit’ as soon as possible since his death seems so likely. Sadly, the medical profession in the shape of doctors have done little to help Mrs Dorbel – on the contrary they seem to feel it is their duty to keep Ben alive:

‘What does the doctor say?’ Mrs Nattle asked.

‘Pah!’ snapped Mrs Dorbell. ‘He doesn’t know what he’s talking about. “Send him to Hope Hospital,” that’s what he says.’ She looked at Mrs Nattle, indignantly. ‘He wants him to get better! Did you ever?’ (p.197).

Mrs Nattle sympathises with Mrs Dorbell’s disgust with the doctor’s unnatural point of view, and suggests that he wants to keep Ben alive though he is dying in order to keep getting his fee. This is why Mrs Dorbell has come too seek advice from another branch of the medical establishment, a certificated midwife.

Luckily, Mrs Haddock feels she may be able to help, though she will need to see Ben to make sure he is really dying, before she can be sure. However, the issue of her fee comes up first in the most blatant and callous manner – she can only ‘help’ Ben if she is paid in advance: ‘Ten shillings it’ll cost you – money down, or I don’t perform’ (p.203). Mrs Dorbell is unwilling to pawn her pension book to raise the ten shillings ‘advance’ unless she can be certain of a result, but in the end is assured by Mrs Haddock’s ‘professional’ judgement that Ben really is dying, and will just need a little help to complete the process (she shifts his position in his bed so that this old and very weak man who is struggling to breathe, suffocates). The title of the story, ‘The Practised Hand’, implies that this is not the first time and will not be the last time Mrs Haddock has performed this lethal act for a fee. Mrs Nattle draws some small commission (in the shape of a whisky) from Mrs Haddock for her introduction of a new client (that is Mrs Dorbell, rather than old Ben). Mrs Nattle also offers immediately (after another whisky from her own stocks) to accompany Mrs Dorbell to make the life insurance claim:

‘Come on, now, get your shawl and I’ll go with you to see about the insurance money . . . I know all the ropes being as I drawed on my husband’ ; with sudden vehemence: ‘They’re a lot of rogues and vagabonds, them fellers; got to watch ’em like a cat watchin’ a mouse, you have. Take advantage of an ig’orant widow woman and stare her in the face as bold as brass’ (p.210).

The irony of these poor female victims being (if only potentially) the easy prey of insurance agents (though Mrs Nattle casts themselves as the cat rather than the mouse!) completes Greenwood’s most ironic narrative.

Greenwood also adapted this story into a one act play (his only short play), which played with some success, though a number of reviewers thought it crossed a line. Thus The Stage reported fairly positively on the drama of a Hulme Hippodrome production opening on 1 July 1935, but was unsure how much life it would have in the theatre because of its ‘Grand Guignol’ contents:

The piece is a composite of comedy and tragedy. While Mrs. Dorbell’s maudlin ways and Mrs. Nattle’s mean-spirited subtlety induce some laughs, the underlying current of stark horror gives something of a Grand Guignol touch to the proceedings. Convincingly played, and produced with that expert attention to detail for which Reginald Bach is noted, the piece provides another example of Mr. Greenwood’s skill in portraying human nature in the depths. How far it will be generally acceptable remains to be seen, but it certainly lacks nothing in presentation (5 July 1935, p.7).

‘Grand Guignol’ refers to a style of horrific and sensational drama developed at a Paris theatre with this name in the last few years of the nineteenth century (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Guignol) and which flourished particularly during the inter-war period. A review in The Era also gave it this genre-label and similarly thought the play effective but undesirable, while implying that this was also why the short story version had been rejected by magazine publishers (not in fact a history of which we have any records to my knowledge, though it is perfectly plausible and might perhaps have been referred to in a programme note by Greenwood – sadly I have not so far found a copy of the programme for the short run of this short play):

First written as a story, it got into print only on a last chance, after a long series of rejections. As a one-act piece, it has not cast off its repugnant features (3 July 1935, p.10).

The most shocked comment on the play version came in a review of The Cleft Stick short story in the short story collection in the Manchester Guardian by Thomas Moult: ‘how a play which any kind of audience could stomach had been made out of it . . . passes comprehension’ (17 December 1937). Clearly, Moult did not think the The Practised Hand should be staged at all. The play did not have a long run, though that might partly be because there are generally issues of audience appeal and financial return with short plays, as well as the piece’s grim comedy of death and money. Greenwood always (quite reasonably) listed The Practised Hand with his other published works under plays, but it was not published by either Cape or Samuel French (who both perhaps saw it as having limited appeal to either readers or performers, professional or amateur).

If we can be certain that Greenwood was (in the main) writing sympathetic portrayals of Mrs Bull, the illegally practising handywoman, across two texts, what is he up to here with his plainly severely negative, critical, sinister and grimly comic representation of the certificated midwife, Mrs Haddock? It seems to me that she fits into Greenwood’s general construction in his fiction of the corrupting effects of acquisitiveness on humanity and fellow-feeling and on a certain scepticism about the relation of conventional respectability to actual honesty. Mrs Haddock is strong on tidiness and on her own superiority to the likes of Mrs Nattle and Mrs Dorbell, but all three are shown as equals under the skin in their attitudes to money and to using others for their own benefit. Mrs Haddock can display her certificate in a frame and her qualification on a brass plate, but those marks of professional peer approval plainly do not in this narrative verify her ethical standards. I do not for a moment think that Greenwood is asserting that all certificated midwives are utterly untrustworthy, but in the world of Hanky Park the certificated midwife and the uncertificated handywoman are contrasted though not in the terms the Institute of Midwives would have expected. I note the contrasting animal names each bears: Haddock surely implies that she is a cold fish, unfeeling, while perhaps Bull implies the bull in the china shop – a hot-blooded and direct personality who may not be subtle but who responds to things as they happen and always make her presence felt? Indeed, going back to the interaction between legislation and practicalities which the Midwives Acts had to face, we might ask what kind of certificated midwife Mrs Haddock was? Though she has some social status (and likewise her husband who is an ‘overlooker’ or overseer in a cloth mill) in Hanky Park, it seems unlikely she could easily have passed the written exam including Latin medical terminology followed by a viva which gaining the Midwives Certificate required. Might Mrs Haddock perhaps have acquired her certificate through the bona fides interim measure which recognised experience as long as good character and respectability could be assured by a clergyman’s reference? This is not to demonise this pragmatic measure which allowed some women of ‘lower’ class to be accepted as professional midwives (as long as they did not look to be obviously working-class handywomen), but it might explain how Mrs Haddock has established a ‘higher’ conventional status than Mrs Bull ever could. I had always thought that Mrs Haddock, unlike Mrs Bull, appeared in only the one Cleft Stick Story, but she gets one further, brief but highly incriminating reference in the novel of Love on the Dole too – which I think no critic has ever noticed. When Sally helps Kate Malloy confront the dreadful Ned Narkey with the fact she is pregnant by him, he at first denies it was him and then blames Kate for not obeying him: ‘Why didn’t y’ do as Ah told y’? Ma Haddock would ha’ shifted it for y’ (pp.166-167). Abortion was of course illegal in Britain at this period except in cases of absolute medical necessity when only a doctor could intervene, which is not say it did not happen especially in poor communities and the very great attendant risks. Certificated midwives were strongly warned not to given even advice about birth control (see chapter 5, ‘Birth Control’ and chapter 6, ‘Abortion’ in Leap and Hunter) and certainly would have wanted any association whatsoever with abortion. If Mrs Haddock was known by such as Ned Narkey to be a procurer of abortions in Hanky Park then she was of course way beyond any possible professional respectability, despite her brass plate and tidy home.

One thing which seems certain is that Greenwood had more than a passing knowledge of the legislation about ‘certificated midwives’ and uncertificated handywomen, and of the underlying assumptions. I assume that he had some personal sense of both kinds of ‘birth attendant’ in his own neighbourhood, probably backed up by the reading of press reports (he was a great user of the library while unemployed). Love on the Dole is, as I think we can see even from the discussion in this article, very open to asserting the importance of material circumstances bearing especially if not only on women, and this is even more the case with The Cleft Stick stories, in which perhaps eight out of the fifteen narratives focus mainly on women’s experience in Hanky Park.

5. Walter Greenwood and Charis Frankenburg Disagree

This brings us to Greenwood’s public differences in 1937 with a well-known Salford-based child-care expert, health campaigner, midwife and champion of birth-control clinics for women called Charis Frankenburg (1892-1985; often named under the conventions of the time as Mrs Sydney Frankenburg). One of the ironies of this exchange between author and campaigner is that both clearly shared the view that knowledge of birth control could materially alter working-class lives and reduce family poverty, though politically she was unlike Greenwood in being broadly a Conservative, despite her commitment to women’s rights across all her contributions to public service. However, she did say in her 1975 memoir that she was never that interested in party politics.

Charis Ursula Frankenburg (née Barnett) came from a reasonably well-off professional background (her father was a college principal in Isleworth, while her mother was an active Suffragette, as was Charis). She started to study at Somerville College Oxford in 1912, but left on the outbreak of war in 1914 to train as a nurse and midwife in Britain (and as various press sources record gained her certificated midwife status ‘by examination’) before working from 1915 in a French maternity hospital established by the British Quakers War Victims Relief Committee. In February 1918 she married a cousin, Captain Sydney Solomon Frankenburg, then serving in France with the Manchester Regiment. After the war they moved to Salford where Frankenburg’s family rubber-making business was based (their newspaper adverts show that among other things they made bicycle tyres and hot water bottles). Charis drew on her experience of nursing and midwifery in an astonishing range of progressive social work and health-care activities in Salford, including the support of ‘properly’ trained midwives and the co-founding with her school-friend and fellow Suffragette Mary Stocks (later Baroness Stocks) of the first birth control clinic outside London. This was the Manchester, Salford and District Mothers’ Clinic, which offered free advice, though ‘only to women who were already mothers’ (see the useful Wikipedia entry on Frankenburg: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charis_Frankenburg; Frankenberg’s Oxford DNB entry provides further detail about her life and work). Frankenburg was a champion of improved maternity care and birth control advice not only in Salford, but nationally, becoming in 1924 a member of the Society for the Provision of Birth Control Clinics and its successors (the National Birth Control Association, 1931-9 and the Family Planning Association in 1939-1998) . In 1938 Frankenburg was appointed a Justice of the Peace on the Salford bench and continued to serve in that capacity until she retired in 1967, aged seventy-five. Her memoir discussed her rich life including her numerous public activities (Not Old, Madam, Vintage: an Autobiography, Galaxy Press, Lavenham, 1975).

In September 1937, Charis Frankenburg wrote a letter to the Daily Dispatch and Evening News, presumably, given the date, in response to the portraits of Mrs Bull in The Cleft Stick. The letter stated that ‘an uncertificated midwife like Mrs Bull is quite impossible nowadays as her trade is quite illegal’. Greenwood replied sarcastically to the paper declaring that:

Mrs Frankenburg has established the illegality of uncertificated midwives. And now we know that abortion, ready-money bookmaking, theft, arson and prostitution are ‘quite impossible nowadays’ since they are illegal (26 September 1937).

Clearly, Greenwood here asserts that legality does not describe the whole experience of reality, and indeed the historical work we have worked closely with suggests that he was right in maintaining that handywomen were still at work in poor areas in the nineteen-thirties. Equally, Frankenburg was perfectly correct in her statement that such work was illegal and that only certificated midwives were meant to attend at childbirths. In fact, Frankenburg and Greenwood had already had a previous exchange about the representation of reality in the same paper on 25 September 1933 in relation to the novel of Love on the Dole. This was not to do with handywomen and midwives but with the general representation of Salford; Frankenburg thought it gave only ‘a caricature of the city’ and disputed that workers began work at 6 am and that the Police used truncheons on the Means Test protesters. Greenwood answered the latter charge by saying that he was himself hit by the police at the Battle of Bexley Square (not something he ever refers to again elsewhere) and that Love on the Dole was set in 1917, when all the works did begin at 6 am. This is an odd defence because the timescale of Love on the Dole precisely because of Harry Hardcastle’s seven-year apprenticeship and the Means Test protest towards the conclusion must run from 1924 till at least October 1931. However, the novel does have a number of memories of the Great War, including one where Harry recalls Mrs Bull (in company with his mother Mrs Hardcastle) showing her humanitarian sympathies by lamenting that the soldiers killed in the trenches from Hanky Park are not even adults and are being sent to fight a war not of their making:

A vivid recollection of the war years occurred to him. He saw himself standing on the kerb clutching his mother’s skirts and thrilling to the martial music as he watched the latest batch of Lancashire soldiers marching to their death in the Dardanelles. He had thought how fine and big and strong the nineteen-year-old soldiers had looked and had been strangely perplexed by hearing his mother say, to Mrs Bull who stood with her:

‘Ay, ain’t it shameful. Childer they are and nowt else. Sin and a shame, Mrs Bull. Sin and a shame.’ ‘Them as start wars, Mrs ’Ardcastle,’ Mrs Bull had replied, emphatically: ‘Them as start wars should be made t’ go’n fight ’um. An’ if Ah’d owt t’ do wi’ it, fight ’um they would. They’d tek no lad o’ mine. Luk at them lot there, boys an’ nowt else’ (pp.75-6).

Charis Frankenberg might or might not have quite shared this view (though she was a keen supporter of war veterans). It seems a pity that she and Greenwood, who actually shared a conviction of the key role which ignorance of family planning played in the reproduction of poverty should have differed so markedly in public.

6. Some Conclusions

The quite extensive attention Greenwood paid to the characterisation of his handywoman Mrs Bull (and the slightly less extensive portrayal of his midwife Mrs Haddock) suggest how much he had reflected on the position of women in Hanky Park, and on how their lives and those of their children and indeed husbands were unnecessarily worsened by a socially enforced unwillingness to allow general access to the very material ‘facts of life’ as well as to key issues in women’s lives and in maternity care. This persistent theme in his work also shows that while he was in many respects a supporter of mainstream Labour Party policies, he was more than capable of taking an independent line and supporting causes that the leadership had been unwilling to support as too controversial. As Leap and Hunter remark,

Birth control became part of the political agenda in the 1920s when women in the Labour Party fought hard to get their party to support birth control provision. They were to be disappointed though. In 1924, the newly elected first Labour government refused to accept responsibility for such services (p.84).

This political refusal to engage with birth control advice stemmed from a number of anxieties, including that it would play poorly with male voters, and that it would be an intervention in personal life and considerable controversies about birth control, which some argued would lead to a reduction of the British population, or to ‘promiscuity’, not to mention a confusion between birth control and abortion, and probably a general embarrassment about the whole topic. This did not of course stop committed campaigners like Charis Frankenburg, though advice about maternity and family planning remained scarce and patchy until at least the nineteen-sixties.

In a quiet way that was nevertheless not too discrete to be undetectable by contemporary readers and viewers, Love on the Dole in each of its three forms persisted in addressing that vital area of loud political and popular silence. Many cinemas advertised the film as only suitable for adults and/or stated that those under 16 years old would not be admitted, or simply added that it was certificated by the BBFC as an ‘A’ film (an advisory only certificate indicating the content was more suited to adults). However, a few others took a different approach. Strangely enough, the Lancashire Barnoldswick & Earby Times on 7 November 1941 (p.2) in its advert for the film sternly stated both that it was not suitable for children and that under-16s would not be admitted. However a month later they switched from a prohibition to an exhortation, declaring that the film ‘must be seen by all over 16s’ (5 December 1941, p.6). This may well have been a unique encouragement. However, it suggests to me a recognition if only by one cinema manager that the film was a contribution to an essential education for young adults, and that surely must be about listening to Mrs Bull, to the potential consequences of pre-marital sex and the desirability of taking thought (or even better, we might think, precautions, where available). In fact from early in the reception of the novel, Greenwood had stressed that it was centrally about the impact on young working-class men and women of a life where free and safe sexual relationships were made impossible by impoverished economic and material circumstances. In his very first press interview about the novel, Greenwood stressed this core concern (though he here makes it notably male-centric):

I have tried to show what life means to a young man living under the shadow of the dole, the tragedy of a generation who are denied consummation in decency of the natural hopes and desires of youth. I have given some relief to grim realism by introducing the characteristic humour of the older inhabitants of Hanky Park (Manchester Evening News, 27 April, 1933, p.1).

There can be little doubt that Greenwood chooses the word ‘consummation’ with great care to bring out both its literal sexual meaning as well as a more metaphorical sense of fulfilment in life more generally. However, his reference to the ‘characteristic humour’ of the four older characters as bringing comic relief rather underplays the importance of at least one of them, for as we have seen Mrs Bull has a vital role as the often generous, sensible, wise and perhaps even heroic Handywoman of Hanky Park. (4)

NOTES

Note 1. See also, for example, Nursing and Midwifery in Britain Since 1700, ed. Anne Borsay and Billie Hunter (Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2012).

Note 2. See Leap and Hunter, p. 10 and their discussion which cites Ruth Richardson, ‘Laying Out and Laying In’, in Association of Radical Midwives Newsletter, July 1982, p.4. I borrow Richardson’s very evocative title phrase in my text above.

Note 3. OED implies that neither ‘birth control’ nor ‘family planning’ were terms in common use between the wars in Britain, with the first usages of the former term being given as 1906 and 1914 with few subsequent uses until the sixties, and the first British usage of the latter term being given as 1945. Much as I admire and constantly draw on OED, this limited list of usages gives a false impression. Though there were certainly continuing controversies about birth control in the period, both terms were in frequent use in the press, as a search for the date range 1900-1949 in the British Library National Newspaper Archive conclusively shows. The Labour-supporting Daily Herald was not unique but was frequent in both its discussion of the topic and its habitual carrying of adverts such as the following, which clearly addressed the issue in entirely practical terms, and was even though suitable for those ‘about to marry’:

A Book advising Birth Control, profusely illustrated, by London’s greatest authority on Family Limitation, invaluable to the married or about to marry. Should be in every home. Over one million copies sold at 6d. Now given away, cost free, to adult readers of the Daily Herald.—Call or write. Marble Arch Pharmacy, D.H.. 24, Marble Arch. London (24 April 1926, p. 6).

Note 4. I have been slightly uncertain whether this article should be given an asterisk to indicate that it is new and original research on Greenwood and Love on the Dole. The key underpinning discoveries and many insights in the piece were made in my 2018 book, that is the identification of Mrs Bull as a ‘handywoman’, the contemporary debates about the legitimacy of handywomen and midwives, Greenwood’s sustained interest in the impact of lack of birth control knowledge on poverty and on the lives of working-class women and his public debates with Charis Frankenburg. Nevertheless, this new article does expand those quite short observations to a more thorough and systematic tracing through of handywomen and midwives in Greenwood’s two thirties Hanky Park texts. I have therefore concluded that this is a new and original contribution to knowledge, though I would hope that any reader interested in this topic would read both the original brief roots in my book as well as the better developed discussion here (for the first shoots of the argument see Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole: Novel, Play, Film, Liverpool University Press, April 2018, pp. 14, 73-74, 82, 88-90).