Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg collaborated on just one book, The Cleft Stick, or ‘its the same the whole world over’ (Selwyn & Blount, 1937): I believe it was a significant achievement of which much more note should be taken. It consists of fifteen stories nearly all with a single illustration by Wragg, or to be a little more precise it consists of fourteen stories each with one illustration, plus one final autobiographical piece by Greenwood which exceptionally gets two illustrations by Wragg (text pp. 212 – 222, drawings on unnumbered pages between pp. 214 and 215, and 218 and 219). Both of these drawings include, if as part of two variously larger narrative scenes, portraits of Walter as a schoolboy, as imagined in response to the fragment by his friend and collaborator, Arthur Wragg, who of course did not actually meet Greenwood until the writer was 32, in 1935. This article is I think the first to note that Wragg had actually done these two imagined/reconstructed portraits of the schoolboy Walter, and will give an account of how Wragg pictures his friend and interprets Greenwood’s ‘Autobiographical Fragment’ in drawing. It will also conclude by thinking through why Greenwood concluded the collection of his first-written short stories with an autobiographical piece.

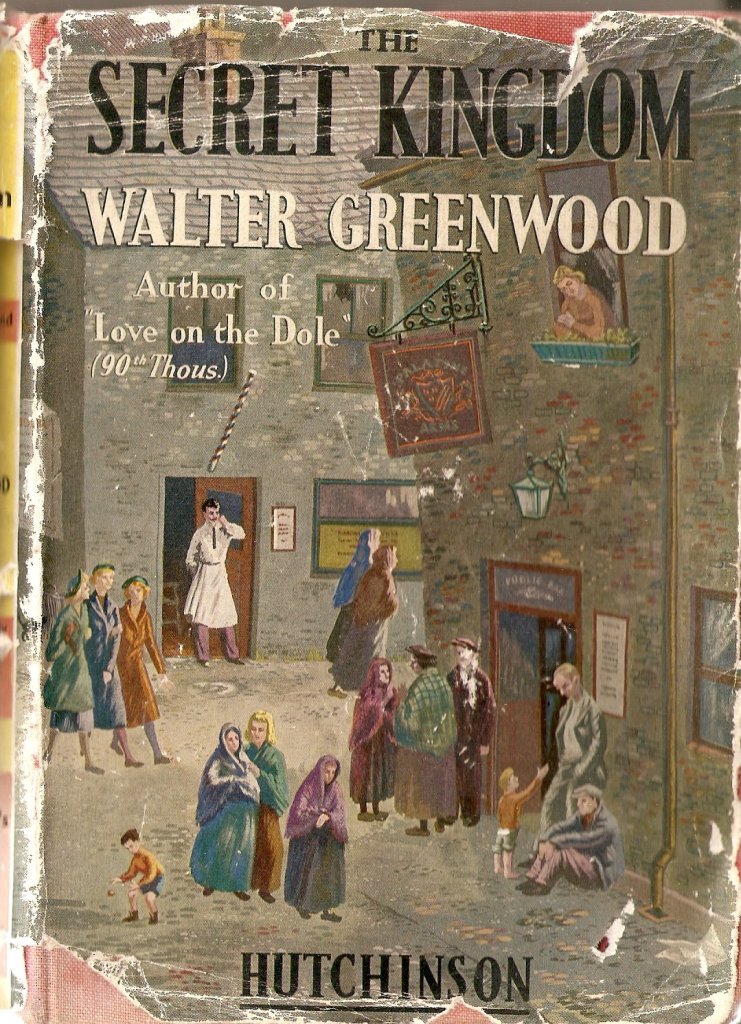

The first illustration comments wryly on the Greenwood family’s attempts to raise themselves a little in the social hierarchy of Hanky Park. This was driven by Walter’s mother, Elizabeth Matilda, nee Walter: ‘Maternal ambition was responsible for my enrolment at the Langworthy Road Council School where a “better class” of boy was reputed to attend’ (p.212). In fact this was part of a whole programme of advancement for the family for it went hand in hand with a relocation of the business and housing of the Greenwoods. (1) Tom Greenwood was a qualified hairdresser and ran a convivial barber’s shop in Ellor Street, where Walter was born. It was convivial partly because barber and clients had frequent recourse to a neighbouring pub. Greenwood returned to his parents’ early married life in his 1938 novel The Secret Kingdom. In this lively and colourful dust-wrapper for the Hutchinson 1939 reprint edition the illustrator imagines the helpful / unhelpful proximity of the barber’s shop and the Palatine Arms public house, as well as the hairdresser with fine moustaches based on Walter’s father.

Elizabeth Greenwood had her doubts about the balance of outgoing and incoming monies in this economy, though Tom always maintained that it kept the barber’s shop busy. However, on top of this day to day economy, Greenwood’s father was prone to fairly regular ‘lapses’:

He carried his clothes magnificently, but he could not carry liquor. Spasmodically he indulged heavily and I have vivid recollections of witnessing his signature to The Pledge to abstain from alcohol. Indeed, I think I still have some of the Temperance Society’s cards testifying to his vow. Much can be forgiven him for his, like mine, was a brutalised childhood (p.213).

Walter must have been witnessing these repeated pledges to abstain between his fifth and twelfth years. His father’s addiction clearly had powerful effects on the family and their potential happiness. Elizabeth’s reform programme seemed rational: ‘Thinking to reform him my mother persuaded him to move from the slum shop in which I was born to a shop in a better neighbourhood. Across the way was the School’ (p. 213). Sadly, it did not work out: Tom did not quickly establish a new clientele, and Greenwood’s memory is that at the end of his first day at school he returned to find a bailiff in pursuit of the rent. Having no spare resources, his parents had only a pragmatic solution open to them:

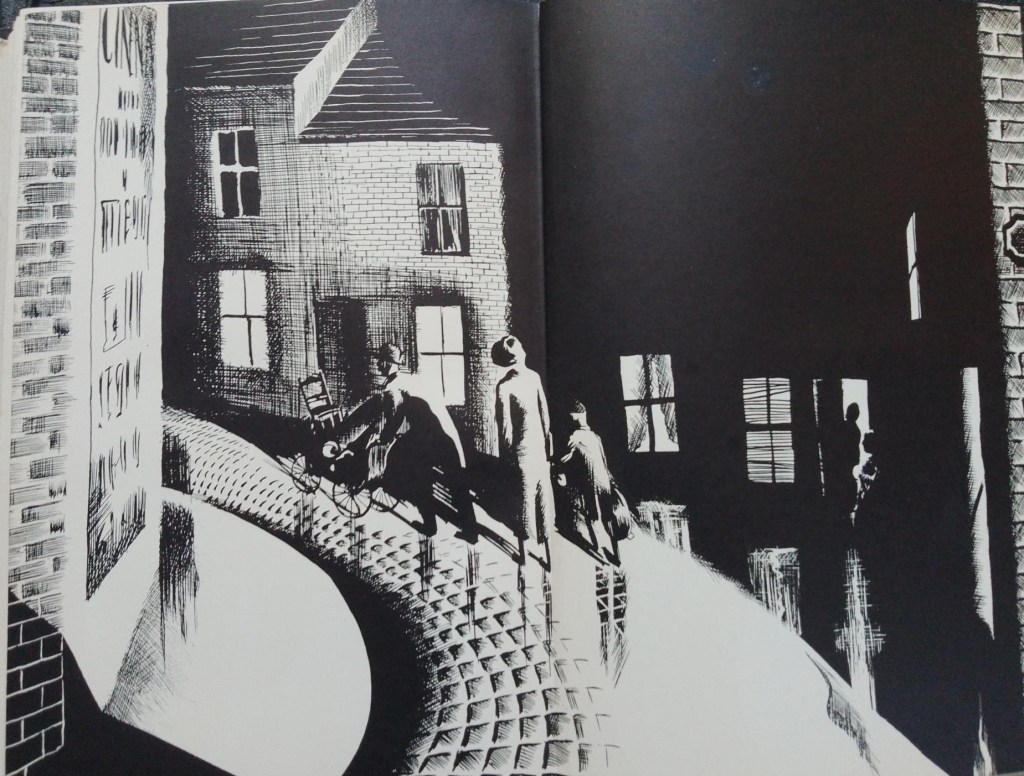

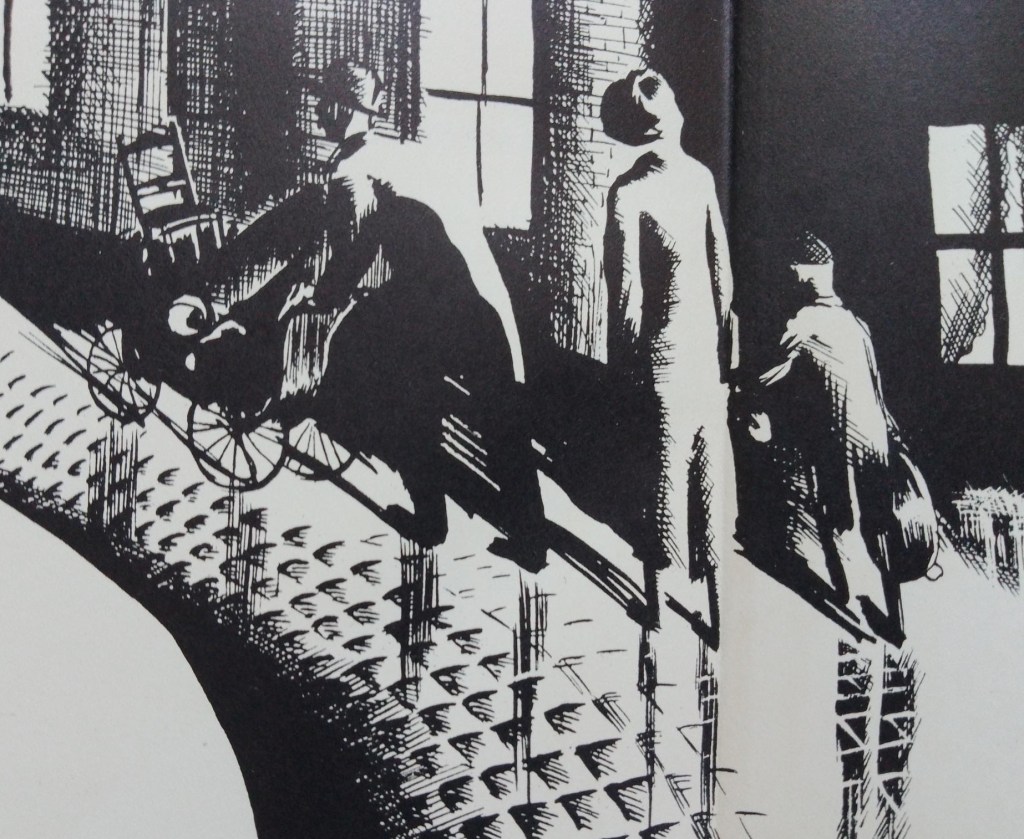

Our removal from this shop to another back in the slums again was effected with the aid of a perambulator. The streets were wet that night. I still see the silhouettes of my parents trudging in the darkness, not speaking. I dragged on my mother’s skirts, but I don’t think she was aware of the hindrance. My father carried himself very erect and with tremendous dignity as he usually did in such emergencies as this (p.213).

Greenwood’s prose here prefigures the deadpan style he applied to his memoir There was a Time some thirty-three years later in 1967. His parents clearly have many emotions about what has happened to them but only their external postures are described, without explicit attempt at interpretation. An ’emergency’ is presumably how Tom Greenwood would have seen the situation – something which had occurred quite unexpectedly and without warning – hence his expression of dignity (yet as the ‘usually’ indicates it is not actually that unprecedented a situation for him). So too, Walter’s own memories are confined to visual images he cannot forget – the wet streets, his parents’ silhouettes in the dark – without overt expression of subjective feeling either at the time or in retrospect. The reader must imagine what all the parties felt.

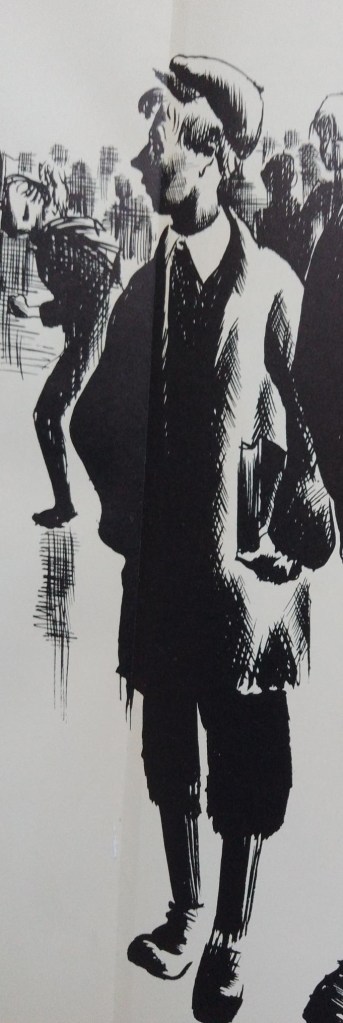

Wragg’s first Old School drawing shows his sensitive reading of this paragraph, capturing just that external scene but also its implied inner family drama.

Greenwood notes that the family (and by this point with the addition of his sister Betty) was left in a dire situation by Tom Greenwood’s early death a few years later in 1912, aged forty-five, of lung-troubles probably in addition to drink. However, Greenwood unemotionally adds that this was not a novel state:

My mother, my sister and myself were left entirely without provision. Not that this was any real catastrophe since my father’s habits had more or less accustomed us to this’ (p.218).

Nevertheless, Greenwood did continue at the allegedly better school, though found little satisfaction there:

To me, the Old School was a place to be avoided, a sort of punishment for being young . . . The teachers’ disgust of us was only equalled by our disgust of them . . . the handbell knelled us to imprisonment from 9 a.m. and 2 p.m. We were released at noon and 4.30 pm (pp. 215, 216).

The latter years of Greenwood’s schooling were affected by the outbreak of the First World War, and by military exigencies. Langworthy Road School was commandeered as a military hospital (a role for which it surely was not well-suited) and its pupils had to share another school premises: ‘Factory idiom was introduced to the time table. There were to be two shifts’ (p.220). This led to instant territorial dispute between the school populations:

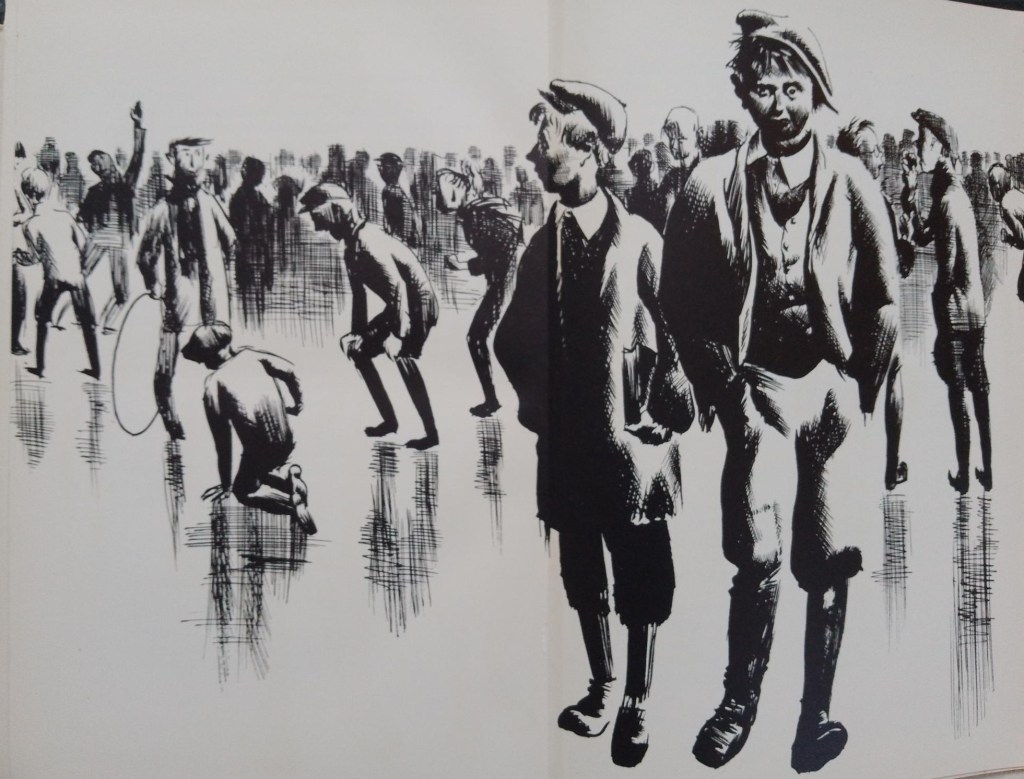

The two schools despised each other. We were regarded by the others as interlopers. Our hostility and contempt for them were unconcealed. In those days it was customary for the school’s best fighter to carry the title ‘cock o’ the school’. He held the name while he was prepared to defend, successfully, his title against all comers. Billy Bonny was our man. And since his family, like mine, was fatherless and also in poor circumstances, a vague affinity existed between us. None dared jeer at me for being the recipient of tickets for free meals since Billy, too, also received them. . . .

The ‘cock’ of the other school, a hefty rough-looking boy, arranged to meet our man after five o’clock. Both schools, yelling, attended the assigned place. All I remember was being crushed and pushed, swaying with the crowd and yelling until I was hoarse. Finally the crowd broke, Billy, fists clenched, flushed, panting, an eye half shut, flashed by, carried shoulder high. The vanquished lay alone, blubbering in the mud (p.220).

This seems an unlikely context for Walter, whose mother made him learn Wordsworth poems off by heart before letting him go to play in the street, but that is exactly the point: this was a context for him even if not one he had chosen (and remember this was meant to be a school with a ‘better class of boy’). This is an aspect of his brutalised childhood: that there must be a ‘cock’ and a fight is taken as given by all, perhaps against the background of both the expectations of working-class masculinity and the omnipresence of the adults’ war – though one notes the detail of the weeping loser returned to his real status as a vulnerable child (curiously Greenwood also recalled the fighting culture of ‘cocks o’ the street’ in his Hanky Park childhood in his very last interview in 1973- see Note 3). At the same time Billy is a kind of protector who shields Greenwood, especially from any comments about free meals, though Walter cannot himself call the relationship anything stronger than a ‘vague affinity’.

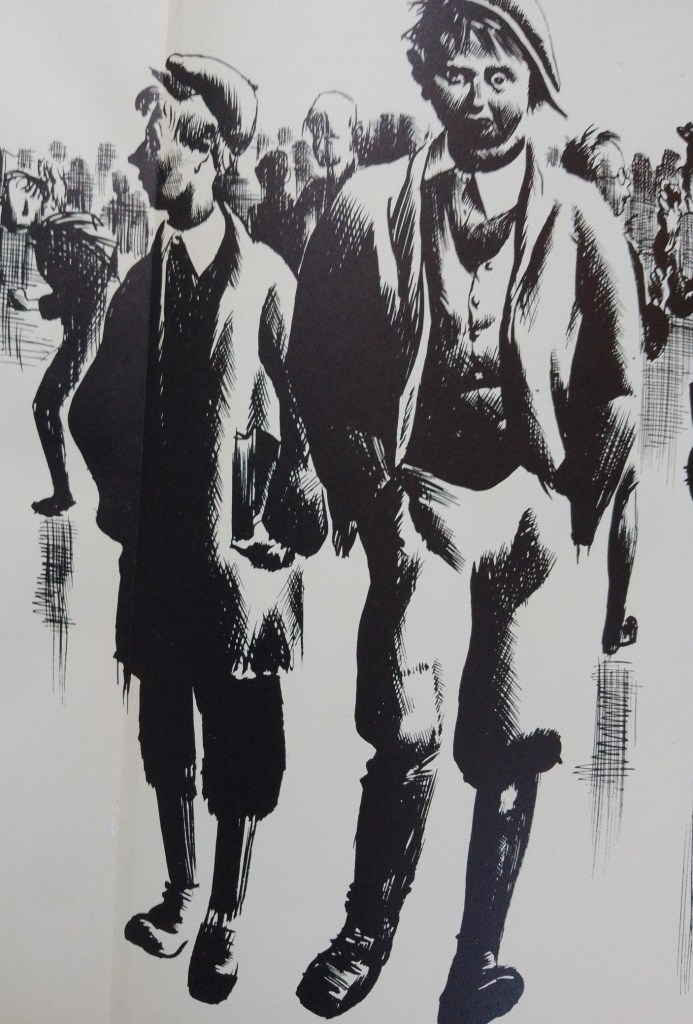

It is this strange relationship, brought about only by a shared lack of father and means, which Wragg focusses his second Old School drawing on.

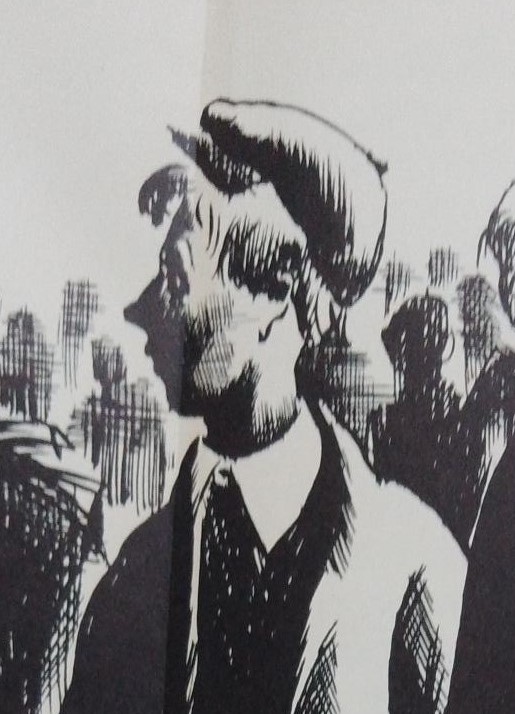

However, perhaps the most striking feature of Wragg’s portrait of Walter is his subject’s half-turn away from his companion Billy and away from the viewer. Certainly it gives the illustration a dynamism which might not otherwise be there but also creates a certain mystery for the viewer: if Walter is turning to look at the larger boy in the middle-distance with a raised arm and face is this because he is a threat or is he someone with whom Walter might actually have more affinity (or something more) but who he cannot easily join at present? Or is it that even then Walter is a keen observer of other people? We cannot know but are repeatedly invited to keep reading the fascinating image which both relates and does not definitively relate these groups of boys who form, for a while, a whole society. The schoolboy in profile, particularly the nose, mouth and chin do catch the look of the adult Walter, as I think this comparison of a further detail of the portrait and a photograph from 1934 suggests. The photograph is a scan by the Author from the original found in an early copy of Love on the Dole which Greenwood had given and inscribed to an otherwise unknown ‘comrade’, ‘Mrs Henrietta Russell’ on August 5th, 1933 (I have flipped the photo from its original orientation to give a similar left profile to Wragg’s second school portrait).

Though ‘The Old School – an Autobiographical Fragment’ was what Greenwood (and Wragg?) decided to close The Cleft Stick with in 1937, it had in fact first been published three years earlier, having been commissioned by Graham Greene for his anthology of school experiences The Old School – Essays by Divers Hands, published by Jonathan Cape. There the piece had been titled simply ‘Langy Road’, with a square bracketed sub-title: ‘A Salford Council School’.

As Natasha Periyan points out in the most substantial discussion of Greenwood’s piece, ‘despite Greene’s original intent that The Old School would be about “the horror of the public school”, the collection also contains a contribution on state education’. (2) I think Greene’s invitation to Greenwood might well have been an afterthought designed to help the new author whose novel he had praised in his Spectator review in May 1933, both in terms of further publication and perhaps a fee. In that respect Greenwood’s essay does seem the odd one out in the anthology, but as Periyan also points out Greenwood in writing it made some specific points to make clear that his school was in every way alien to the culture of a public school, and so does something to tie it in to the anthology topic, if only by contrast. One notes indeed that The Cleft Stick title of the piece borrows something from the anthology publication in renaming it ‘The Old School’.

Periyan also analyses how important for Greenwood in this piece as well as in Love on the Dole (the novel) and some key journalistic commissions was the potential political empowerment of working-class education, and by implication the deadening effect of what he and his peers experienced as their default schooling. Greenwood also makes clear that his bad school experience was bad for everyone trapped in the system:

The teachers’ disgust of us was only equalled by our disgust of them and of the School. There was nothing at all of the Harrow-and-Eton Alma Mater affection (The Cleft Stick, p.216, p. 77 in Greene’s anthology, cited by Periyan at location 3060).

It seems worth asking, though, why Greenwood (and Wragg) decided to close their illustrated short story collection with a sole autobiographical piece. Most of the fourteen stories were written when Greenwood was unemployed between 1928 and 1932 and he names in his ‘Author’s Preface’ just two as written more recently, presumably in 1936, ‘to complete the volume’: ‘Patriotism’ and ‘Any Bread, Cake or Pie?’. This seems to put the autobiographical fragment on its own both in terms of genre and in terms of composition in 1934. It seems unlikely that it was put at the end at random since the collection seems carefully conceived. However, it might be that I have not properly weighed the other autobiographical piece which is there in the book at the beginning, plain to see. The ‘Author’s Preface’ is a substantial autobiographical piece in its own right which carefully explains why and how Greenwood attempted with great determination to become a writer instead of a ‘bookkeepper-correspondence-clerk-typist’ and how this book of stories came into being (Preface p.8). Perhaps this and the autobiographical fragment bookend The Cleft Stick in reverse order with accounts of how school destined him for nothing but low-wage unskilled work and of how he defied those odds through the creative work which the short story collection finally evidences after much trial:

It was not necessary for me to look beyond my own case to see that the sooner I eschewed ‘honest toil; the better it would be for me and my immortal soul, for my prospects were such that, had I surrendered, I should have landed myself on a clerk’s stool at thirty-five shillings a week for the rest of my life . . .

Therefore I chose seventeen shillings a week on the dole, and spent my leisure observing and committing my observations to paper in the form of these short stories and a vast crude novel of noble proportions which now awaits the ministrations of a more practised hand (p.8).

The autobiographical fragment suggests just how deeply the schooling they were offered seemed empty of value to Greenwood and his peers and was another contribution to a ‘brutalised childhood’: it gave them no possibility for realising their potential. Greenwood contrasted his own and his sister’s schooldays (despite her own nonconformity) and ironically recalled the one time when his (parodic) command of language had an impact, if not in his own name:

In the whole of my school career I never won a prize nor an attendance certificate, though Betty, my sister, in spite of her defiant, argumentative nature, which was the despair of her teachers, won the School Merit Prize year after year. I used to help her with Composition and I recall the opening phrase of an imaginative essay on jungle life which I supplied to her and which, I think, gained her full marks. It ran: ‘In the dense forests of Africa, where grows in profusion creepers and all manner of plants and varied foliage, I, a mighty elephant, make my abode’ (p.214).

Of course, this imaginative opening had nothing to do with life (or even ‘jungle life’) in Hanky Park as lived by the Greenwoods and their neighbours, but was derived from books, and tales of other continents and of Empire.

And yet Walter had much potential to be worked on through his own and collective intellectual and creative labour: Wragg’s second portrait perhaps hinted at that potential as already there in his thoughtful and observant schoolboy Walter with book discretely in hand.

NOTES

Note 1. In this account of the Greenwood family in the period between 1903 and 1912 I have drawn some additional detail from Greenwood’s 1967 memoir There was a Time, while mainly following the 1934 account published in The Old School and then republished (more or less) in The Cleft Stick in 1937.

Note 2. In her The Politics of 1930s British Literature: Education, Class, Gender, Bloomsbury, kindle edition, first published 2018, location 3044):

Note 3. See the Kersal Flats interview, 1973 on Youtube, 1.0-9 to 2.12. Sadly, I have not been able to identify the interviewer so far.