1. The Typescript and its Loose-leaf Sheets

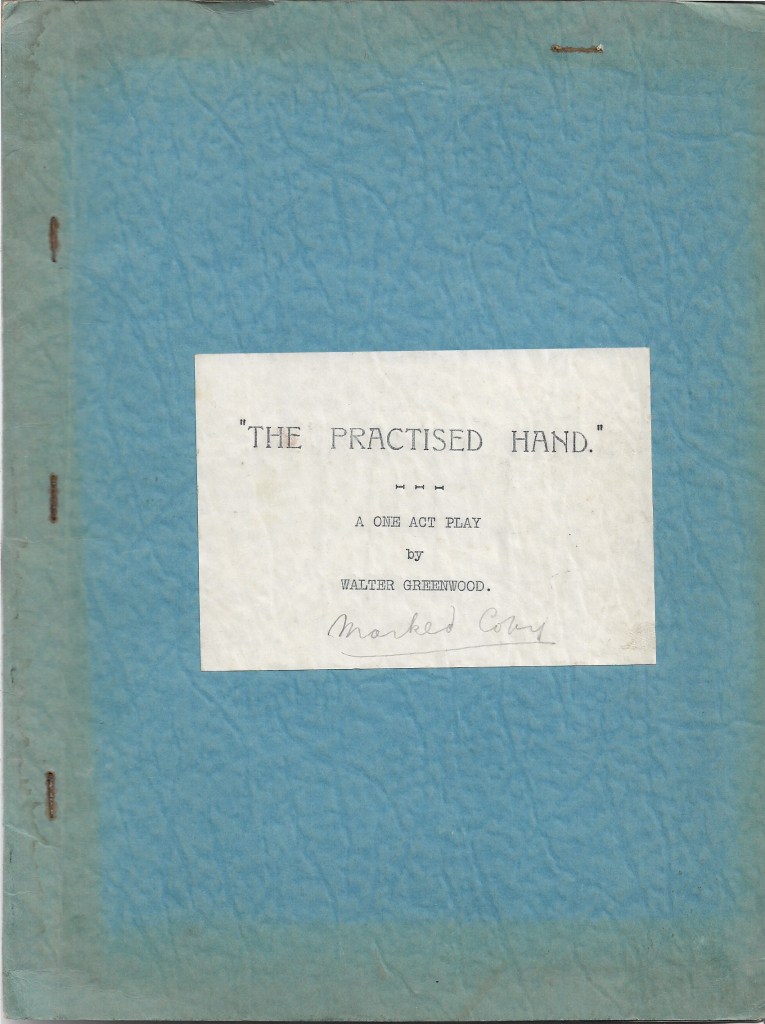

The studio sale of works by Arthur Wragg and Frederick Roberts Johnson held by Lay’s Auctions, Lanner, Cornwall on 13-14th February 2025 brought to light at least one further item of great interest to those studying the work of Walter Greenwood and Arthur Wragg (in addition to the sketch of a dust-wrapper – see Underneath the Lamp-post: Arthur Wragg’s Incomplete Sketch for a New Walter Greenwood Dust-wrapper (1930s? 1940s?) * and Arthur’s Wragg’s Original Dust-wrapper Drawing for The Cleft Stick, and his Original Drawing of an Alternative Design (1936/7) *). This second item is a seventeen-page typescript of Greenwood’s one-act play The Practised Hand stapled together with two title-pages and a cast-list for the first production inside a blue mottled card cover. Found inside the typescript were the following:

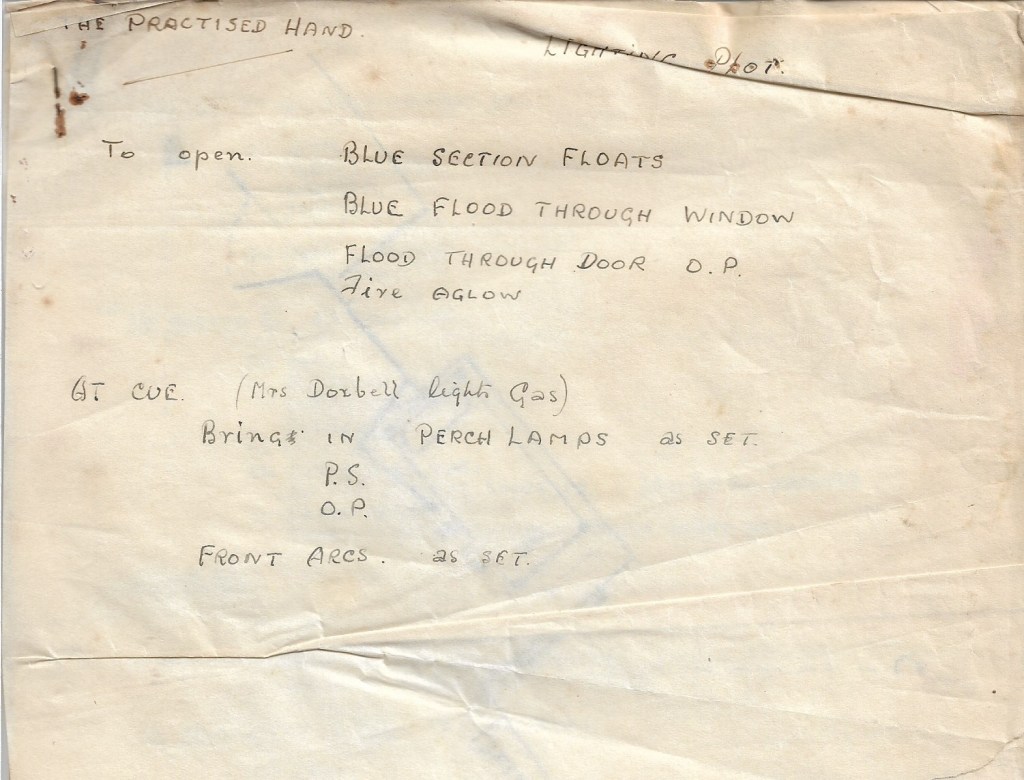

- a hand-written lighting plot in upper-case black ink letters (not I think in Greenwood’s hand)

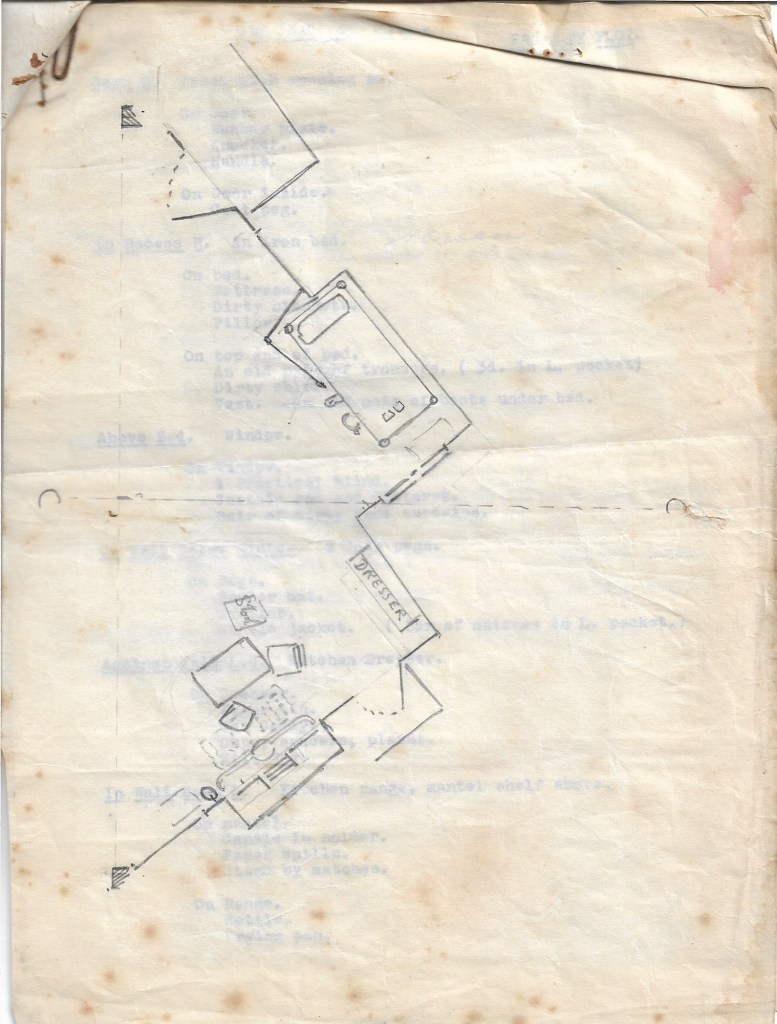

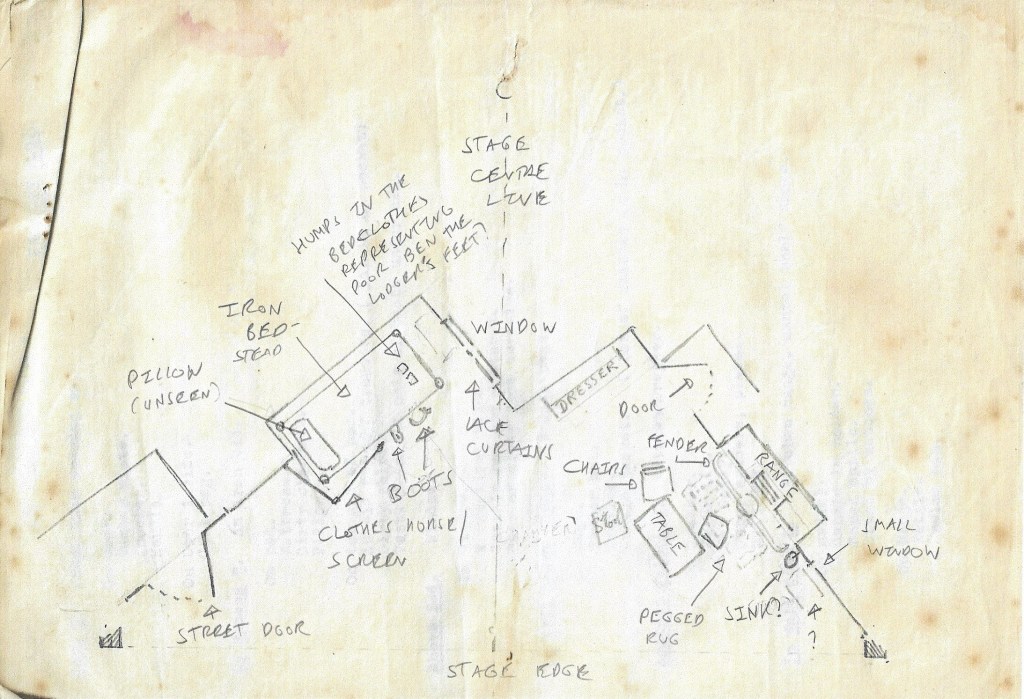

- a pencil-drawn floor-plan of the set

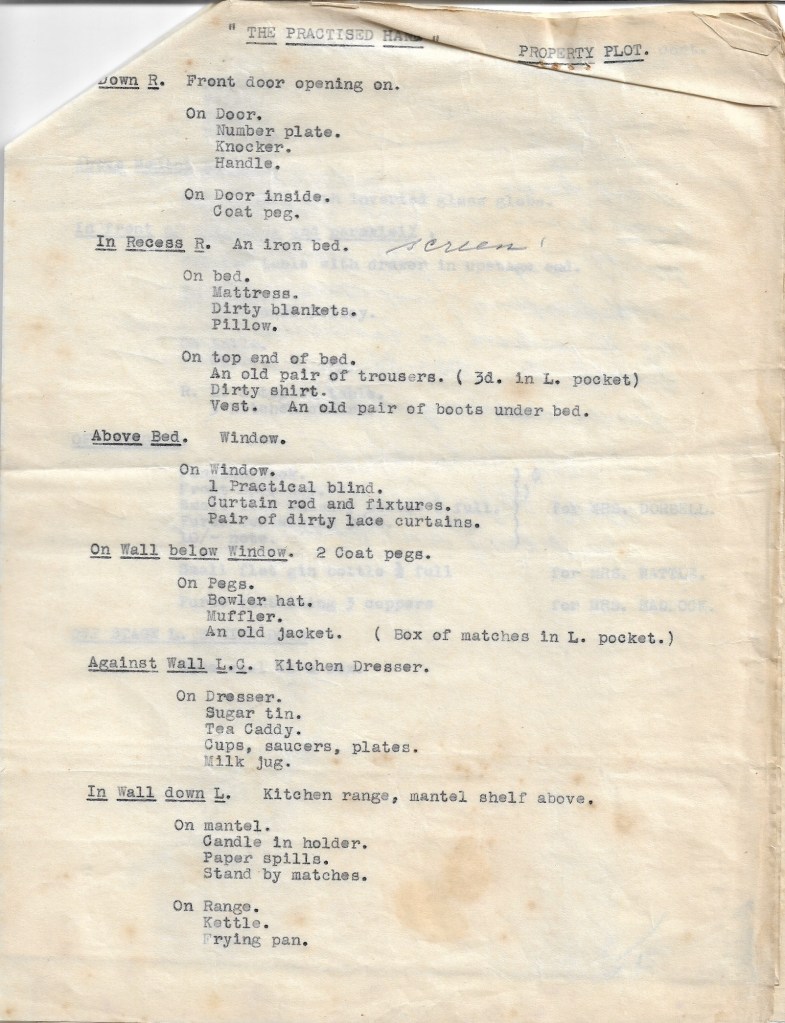

- two typed pages of a ‘Property Plot’

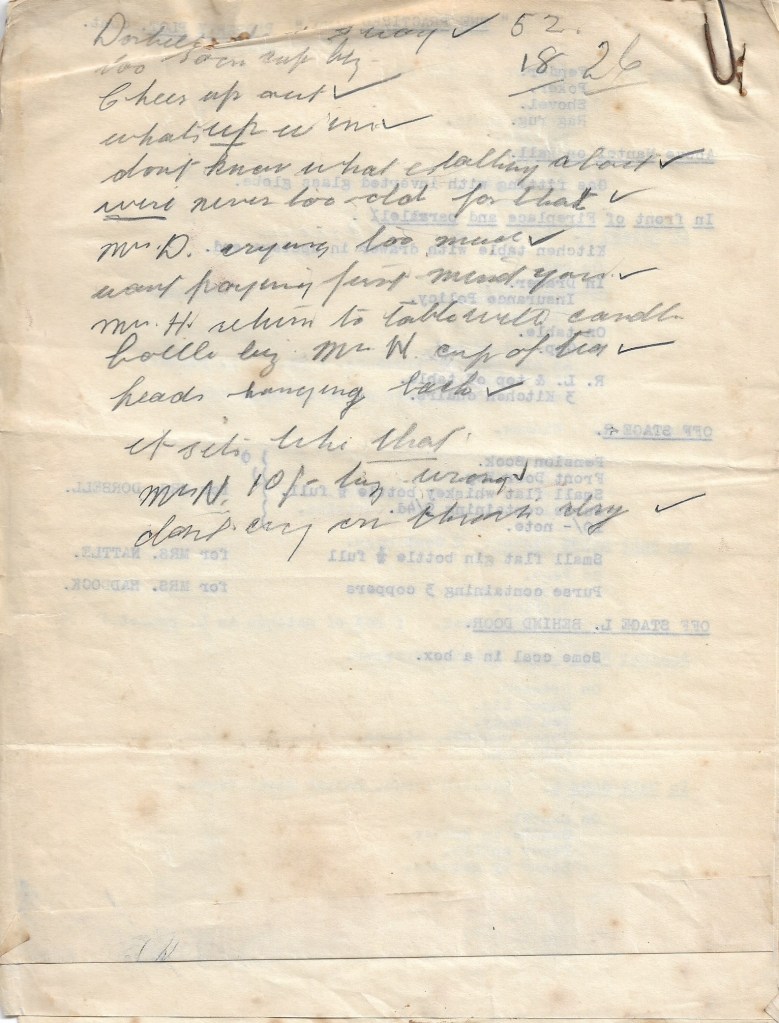

- half a page of pencilled notes about the performance, or probably a rehearsal, and usually focussing on specific lines, in Greenwood’s easily recognisable hand

- two pencil sketches of characters in the play by Wragg.

This item was kindly provided to me by Burwood Books, Wickham Market, UK (purchased 12 May 2025). This article will record and analyse all the material between the blue card covers, in eight sections and a conclusion.

2. The Practised Hand: Story and Play

The play The Practised Hand began its life as a short story, composed during Greenwood’s first explorations of writing when he was unemployed between 1928 and 1931, as is clear from his listing of when stories were written in the ‘Author’s Preface’ to The Cleft Stick (Selwyn & Blount, London, 1937, p. 9). The story concerns a long-term lodger, Ben, who has been very ill for some fourteen weeks. His land-lady Mrs Dorbell has insured his life for a benefit of twelve pounds and ten-pence on death. However, she is beginning to think Ben may linger for a long time and is losing patience. In the pub one lunchtime having a small whisky ‘for her cough’, she meets a neighbour Mrs Nattle who celebrates every pension day with a small whisky, and who becomes interested in her woes and suggests approaching the certified local midwife, Mrs Haddock, who was able to help her with a similar problem when Mr Nattle was suffering and dying excessively slowly and delaying the payment of life insurance. For a fee, Mrs Haddock will indeed ensure that Ben dies more promptly, though, of course, she ‘won’t do anything what’s wrong’ (p.199). Mrs Nattle expects a small commission in the currency of a drink from both parties (for a fuller discussion of the story in its context see ‘Call the Handywoman!’: Birth and Death in Hanky Park (1933-1937) * ).

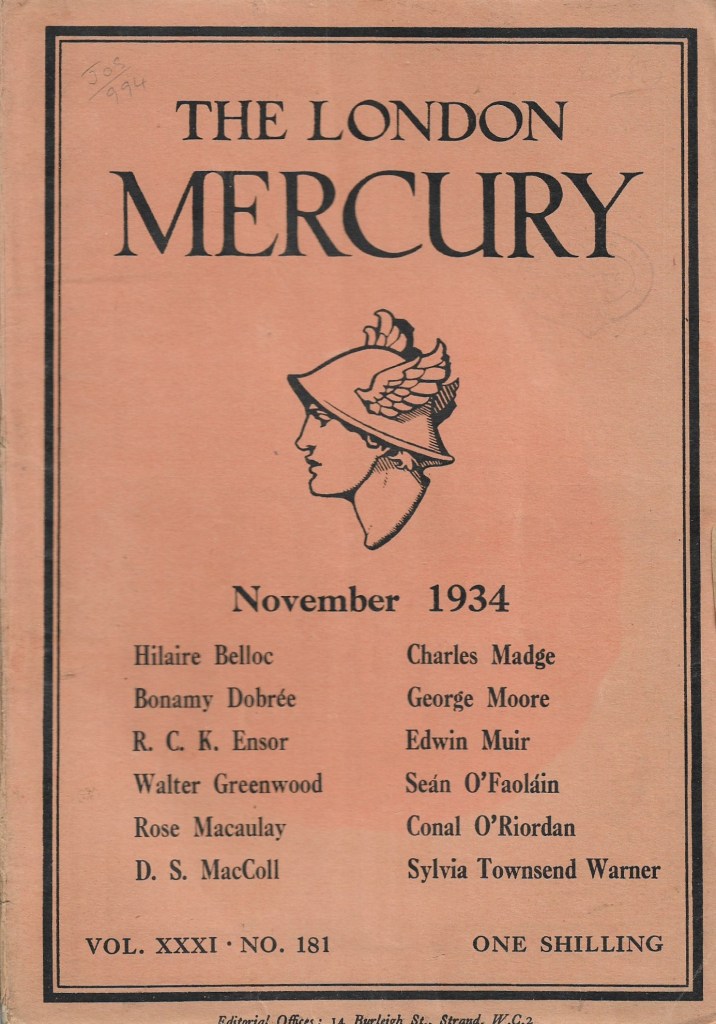

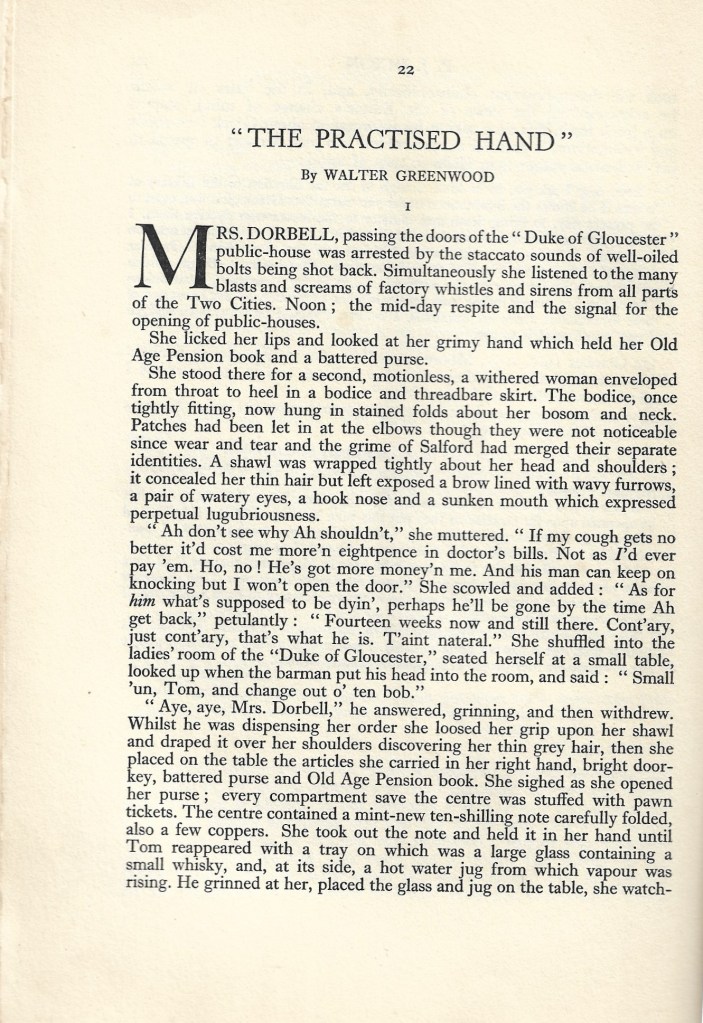

In fact, three years before its Cleft Stick publication the story had been published in the London Mercury in 1934:

Scan of the cover and the first page of the story from copy in the author’s collection (the whole substantial text occupies pp. 22-33); there is also a clipping of the Mercury publication of the story in Greenwood’s clippings book (Salford University Archives, WGC7/6/1). I think Greenwood would have been pleased to be among the authorial company listed on the cover.

Then Greenwood had published the story again in 1935 as his donation to The Centenary Hospital Gift Book – a charitable project to raise money for new buildings at the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital (for discussion of Greenwood’s contributions to two such projects see Walter Greenwood’s Two Manchester Hospital Stories (1935 and 1945) *). Having been very poor for the first thirty-three years of his life, I think it would be fair to say that Greenwood liked to get as much return as possible on his literary capital, and of course like any author he could not be certain that his good fortune in the literary market-place would persist (though he naturally provided the story for the hospital gift book for free). He was also fond of adapting his own work, and after his very successful co-written adaptation of the novel of Love on the Dole into a play version with Ronald Gow, he generally and for the rest of his life tried to place adaptations of his novels as plays, or films, or radio or TV scripts. This helped him in three aims – firstly to maintain a wide audience for his work, secondly to draw attention to the serious social themes he wanted to raise for both existing and new audiences, thirdly to enable him to live in a sustained way on his earnings as a professional writer. He really did not want to go back to being a book-keeper or clerk (see ‘Servitude at the Desk’: Walter Greenwood and Clerical Work (1916-1967)*). He clearly decided in 1935 that The Practised Hand was a suitable candidate for a theatre adaptation by his own hand.

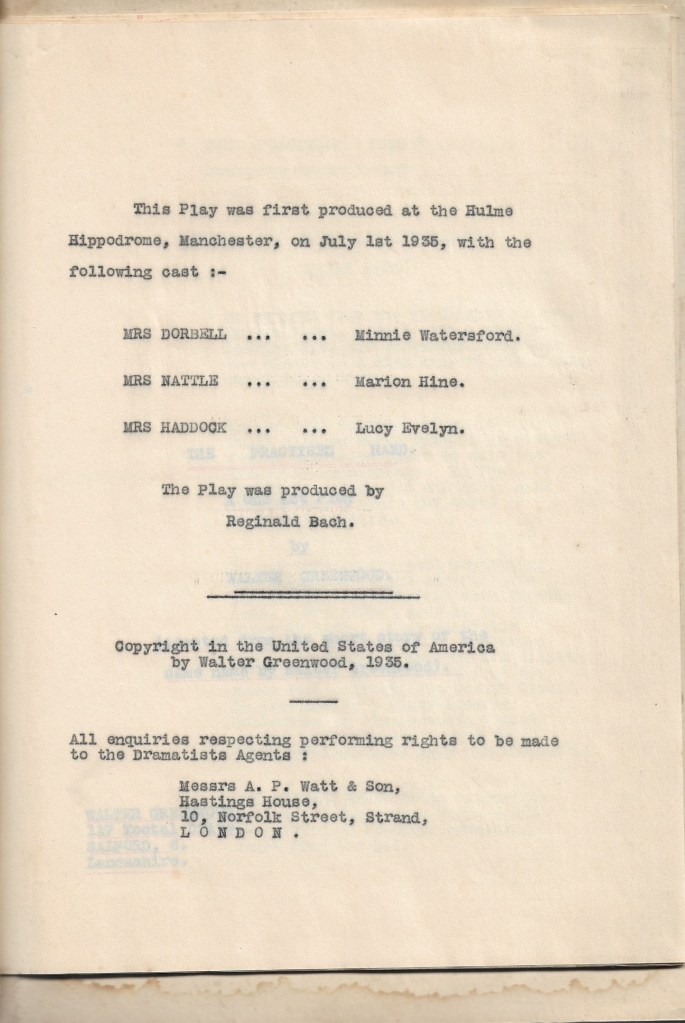

3. Performance History and Reception

The typescript itself records a first performance of the play at Hulme Hippodrome in July 1935 and lists the actors in the three-person cast, and the producer:

Greenwood always recorded the play with his other published works on the inside pages of his subsequent works, and perfectly correctly, since performance is a legitimate entry into the public realm. However, no edition was produced by either Cape or Samuel French who both published editions of the play version of Love on the Dole and between them editions of many of his other later plays. Nevertheless, taking no chances, Greenwood carefully put rights information on this typescript, asserting both US copyright and details of his literary agent, A. P. Watt, for anyone who planned to produce the play in Great Britain. The typescript has importance therefore as the only written text of the play, and though I am sure there were a small number of copies for the small cast, producer and author to use, I do not know of any other surviving copies, not even in the Walter Greenwood Collection in the Salford University Archives (though I intend to donate all my original Greenwood papers to the Archive in due course, if agreeable to the University). The typescript may then in itself be a unique survival, and certainly the associated loose-leaf sheets are very likely to be unique: together the two give insights into Greenwood’s one-act play which could not be derived from any other sources.

There were newspaper notices and a few reviews of this Hulme production in both local and national papers, but mentions were surprisingly few given the ongoing success of Love on the Dole on stage (perhaps it swamped the attention paid to the shorter play?). The Daily Herald published a notice that Greenwood had a new play on and that he was to return by plane from a visit to Gracie Fields at her home on Capri for its opening at the Hulme Hippodrome (29 June 1935, p. 11). The Manchester Evening News review praised the piece while also alerting audiences to its dark tone, though rather implying that it was based on a real event, which is not a known fact:

Mr Greenwood has painted a vivid picture of the depravity which caused this murder to be committed for £12 10s. Minnie Watersford, Marion Hine and Lucy Evelyn play the difficult parts with frightening realism. Reginald Bach’s production has captured down to the last detail the sordidness of the Hankey Park house . . . [there is] exceptional quality in this gripping play (signed N.G.R.B. , 2 July, 1935, p.2).

The Stage carried a concise but precisely accurate plot summary on 4 July 1935, and also characterised the play as a further ‘slice of life’ in Hanky Park, portrayed with ‘grim realism’. It thought the acting and production very good, but had its doubts about whether such a play would be much performed in British theatres:

How far it will be generally acceptable remains to be seen, but it certainly lacks nothing in presentation. The three artists score in their respective roles, and skill is exhibited in the lighting of the scene, an important item in so drab an environment (p.7).

The Era also published a substantial review expressing similar views about the convincing production, accepting its probable truth, but also commenting quite severely on the taste of the piece:

First written as a story, it got into print only on a last chance, after a long series of rejections. As a one-act piece, it has not cast off its repugnant features. It introduces three old women characters such as appear in Love on the Dole, and the chamber-scene in which it is played is presumably in the neighbourhood of the Hanky Park of that play. It is, at any rate, typical of low Salford. These women of The Practised Hand are, however, a source of amusement only if one sees amusement through the very grimness of their realism. A male lodger lies dying in the hovel of one of them, who has him insured; another is ghoulish go-between who introduces a third, who, for a price, can finish him at once, in a way beyond suspicion, to satisfy the impatience of number one. The setting and the conduct of this sordid and successful scheme are both so near to the real thing that the play lacks nothing in conviction. Drink, theft, murder, never overacted, and an atmosphere impregnated with crime itself, thanks to Reginald Bach’s inspiration for the author’s idea, produced the necessary effect on Monday’s audience. There are no other characters but the three women. The Era, 3 July 1935, p. 10).

The judgements of both papers turned out to be correct, for as far as I can see there was no further production of The Practised Hand, professional or amateur. It may be that both content and form worked against it, for it was clearly controversial, and short plays, which one-act plays are by definition, might deter both theatre managements and potential audiences, since they could be seen as not offering a full enough entertainment to make a production financially worthwhile. A one-act play might appeal more to amateurs, but would this one?

Two of the three actresses were experienced, while I can find little trace of the third. Indeed, Minnie Watersford had been on the stage since at least 1891 (in My Jack at her Majesty’s Opera House, Blackpool) and she went on acting until at least 1953 (according to The Stage, 2 July 1953, p. 12). Though The Stage had recorded and reviewed her work as mainly a character and comic actor in repertory over that whole period of sixty-three years, it unusually did not print an obituary, so I do not have a death-date. It did record her celebrating her seventy-fifth birthday in 1952, which gives her a birth-date of 1877 (24 July 1952, p. 12). From her frequent notices in The Stage and other newspapers she was almost never ‘resting’. However, she was looking for work in February 1936 since she posted what was known as a ‘theatrical card’ in The Stage stating that she was ‘Free. Repertory or Tour’ (6 February, p. 2). I wonder whether this was perhaps a consequence of a short run for The Practised Hand? Either by lucky co-incidence, her reputation as a character-actor or through recommendation from Greenwood she went on to play Mrs Dorbell again in one of the Vernon-Lever touring productions of Love on the Dole from early April 1936 until early June 1937, as is recorded by listings of performances at various kinds of theatre, from variety and seaside (if modernist seaside!) to grand, including, for example, the Penge Empire (The Era, 9 September 1936, p. 4), the Bath Theatre Royal (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 20 February 1937, p. 17 ) and the De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill (Bexhill-on-Sea Observer, 5 June 1937, p.5).

Lucy Evelyn (confusingly also often listed as Lucie Evelyn) does not have quite the footprint of Winnie Watersford, but is regularly noted by the Stage in comic, character and supporting parts from at least March 1914, when she played in a revival of an 1892 comedy-drama called Liberty Hall, by R.C. Carton at the Margate Hippodrome (19 March 1914, p. 27). She continued appearing as older married women, aunts or land-ladies in plays throughout the nineteen-twenties and on into the thirties. Her death is noted by the Stage in 1937 (22 July, p.6). Marion Hine cannot have been a newcomer to the stage and her acting in a difficult part was clearly praised, but I can find out very little more about her in the press. I would assume that she too was a character actor of older female roles, but it is surprising if that was the case that the Stage does not have some reference to her. The play must have been unusual then (and might still be pretty unusual) in providing three good parts for older women.

Reginald Bach (1886-1941) had a considerable reputation as an actor on stage and on screen and then as a theatre producer, though that role corresponds more closely to what we would now call a director. The Stage published an obituary recalling his large number of acting roles and work as a producer in both the US and Britain, and noted that he had a success with his production of the play of Love on the Dole on Broadway in 1936 (January 1941, p.6). He was often praised by reviewers for his contribution to the Garrick Theatre, London, production of Love on the Dole in 1935; the Stage noted that along with Greenwood and Gow he took a bow ‘and was accorded a well merited recognition’ (7 February, 1935, p. 12). As the Era review above shows, he was similarly recognised for his contribution to The Practised Hand. The Stage review too praised Reginald Bach for his work on the convincing detail of the set and the lighting: ‘he is again a prime factor in the latest Greenwood play’ (4 July, p. 7).

4. The Typescript Format, the Stage Directions, the Set Floor-plan, the Property Plot and the Lighting Plot

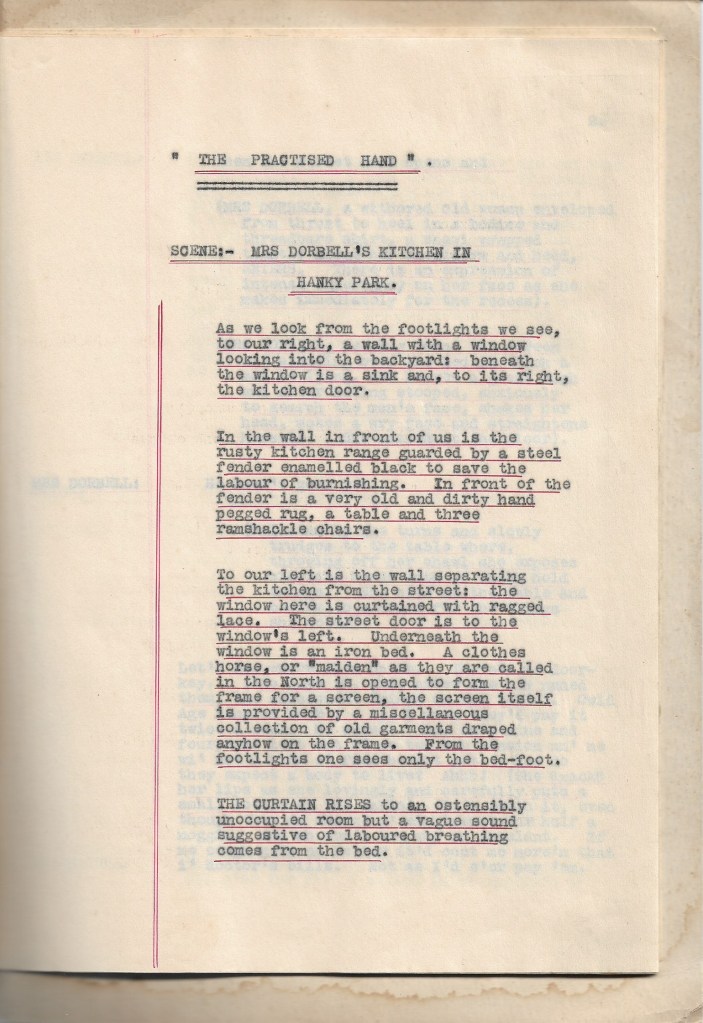

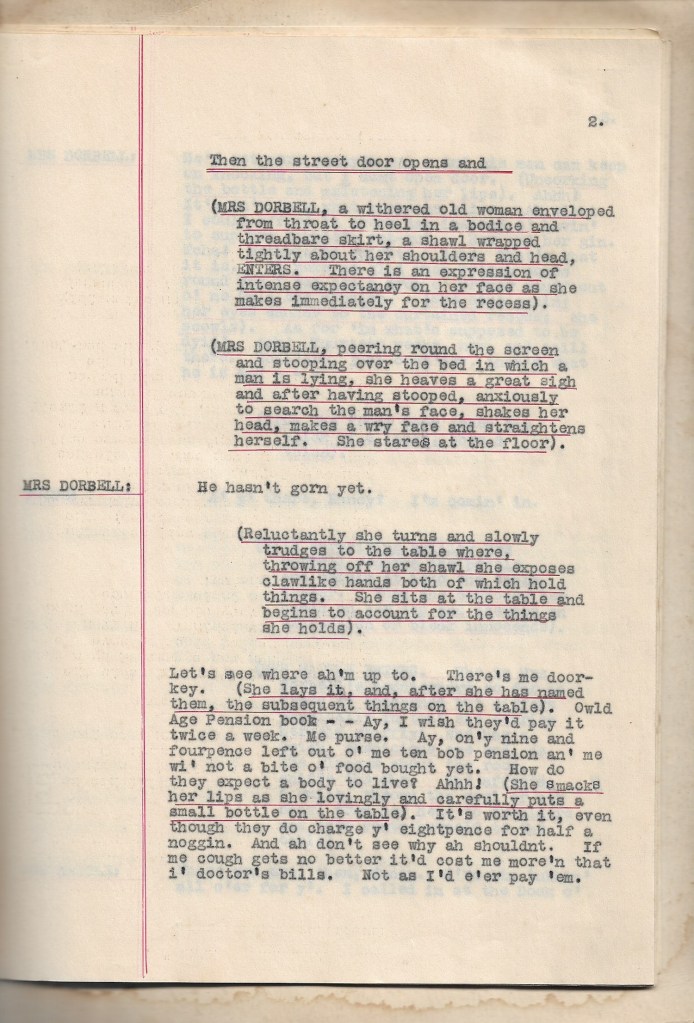

The typescript itself, which I presume without absolute evidence to have been typed by Greenwood himself on his own typewriter, has a quite complex layout, but one which seems helpful in an acting script.

The red underlining here indicates several different things: the title, the location of the scene, and the fact that these pieces of text are all stage directions rather than spoken lines. There is also a double-ruled red line to the left of the page which continues throughout the remaining sheets of the play. On subsequent pages it divides the names of the speakers from the lines they speak. I am uncertain about how this red underlining and other red lining was produced. It seems at first obvious that it is done with a typewriter (which were as I recall generally provided with a black / red ribbon in which the colours could be switched between with a special shift key), since the lines seem very even and fine. However, I am not sure how the double-underlining would have been achieved with a typewriter. Nevertheless, overall the underlining does seem too even to have been done with a ruler and red-ink nib.

This first page of the typescript contains all the stage-directions describing the set layout and corresponds closely with the pencil floor-plan of the set on the separate piece of paper, though there are some differences, including in the placing of the doors, as well as some objects not named in both.

The additions and odd differences from the written set description suggests there was room for some creativity and interpretation, and that it was the work of another hand, presumably that of the producer or stage manager rather than of Greenwood as author.

The ‘PROPERTY PLOT’ of two pages is on the other hand a good match with the written set description, but adds details of some things not evident in the set floor plan, and of course makes clear the required smaller and movable stage properties, such as the exact clothing in the room, the kitchen items on various pieces of furniture, and the off-stage properties carried on the persons of the three characters, particularly in their pockets. Page 1 omits an important prop under the heading ‘In Recess’, and this is added in pencil in Greenwood’s hand: ‘Screen !’. As we shall see, the screen is vital to the working of the play, which could not be performed without it. All the other properties are those we would expect in a play designed to offer a high sense of domestic realism, and in particular a messy and disorderly realism of poverty (the Scotsman said in its review of The Cleft Stick stories that Wragg’s drawings ‘remain in the reader’s memory like a stage setting to some ballad of poverty’, 16 December 1937, p.15). It is of course the dwelling of Mrs Dorbell, and reflects her character and way of life (as Mrs Haddock comments in the story and play versions ‘I never saw such a pig-sty in all my life’ / ‘Ne’er saw such a pig-hole in all me life’ , p.206 and p. 11). The most noticeable props which adorn much of the minimal furniture are probably the textile ones – ragged curtains, dirty blankets, old clothes, many of them clearly belonging to a man. Among the off-stage properties one also notes the ‘small flat whiskey bottle 1/2 full’ for Mrs Dorbell and ‘the small flat gin bottle 1/2 full’ for Mrs Nattle. As the Era review observed, the play is about ‘Drink, theft, murder’ and in addition the two crimes named it is indeed noticeable how persistent the drinking references are – spirits especially are a panacea in Hanky Park, both a ‘medicine’ and the only reward worth working for, though perhaps in truth really an addictive anaesthetic and drug of choice. As several reviews suggest, the atmospheric and scrupulous detail of the set doubtless owes much to the work of Reginald Bach.

To the set design we must add what was also probably the work of Reginald Bach: the ‘Lighting Plot’ (and perhaps the hand-writing here is his too?).

There is some technical stage-lighting terminology here in which I am certainly not expert, but which I will try to interpret as best I can so that we can gain some understanding of the effects aimed at. Overall the aim of stage-lighting is to combine different kinds of lighting equipment firstly to make sure the actors and set are visible to the audience and secondly to create atmosphere, including time of day or night, and specific effects, such as focus or selective visibility, which may change as the stage action develops. The apparatus used for stage-lighting has, of course, changed with new technological developments, for example from the gas-lighting introduced in early nineteenth century British theatres to the electrical lighting which largely replaced it in the first half of the twentieth century, and subsequently in the twenty-first to much more precise and flexible electronic and digital controls and new kinds of lighting effects and indeed light sources. I am assuming that this lighting plot has electric lighting primarily in mind with the kinds of relatively straightforward controls available in the nineteen-thirties (there is a very large literature on stage-lighting but my amateur overview here is derived from the Wikipedia entry on stage-lighting tigether with one more specialised resource, listed below: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stage_lighting).

The lighting plot refers to four different kinds of lights: ‘Floats’, ‘Flood’, ‘Perch lamps’, and ‘Arcs’. ‘Floats’ are lights which were traditionally used in footlights – the row of floats on the stage-edge which ‘were used to neutralise shadows cast by overhead lighting’. A ‘Flood’ is ‘a lensless lantern that produces a broad non-variable spread of light’. ‘Arcs’ are bright lights, which can be set to focus on a specific part of the stage. ‘Perch lamps’ refer to stage-lighting ‘at each side of the stage, immediately behind the proscenium’ (all definitions here are, with the exception of ‘Arcs’, from the invaluable Glossary of Technical Theatre Terms – Lighting, Beginners: https://www.theatrecrafts.com/pages/home/topics/lighting/glossary-beginners/). There are three remaining technical terms in the lighting plot. A ‘section’, refers to different parts of the stage which may need to be lit in different ways or intensities: front-stage, centre-stage and rear-stage. The abbreviations P. S and O. P indicate different positions on the stage in relation to the prompt box, traditionally at stage left (audience right); hence P.S or ‘prompt side’ (audience right) and O.P or ‘opposite prompt’ (audience left).

So we can now, if only rather minimally prepared, discuss the aims and probable effects of this lighting plot for The Practised Hand. Blue light has traditionally been used to suggest night-time or other dim-light conditions. Though the time of the play’s opening is not specified in stage directions the text itself suggests it is set in the morning and early afternoon some time between 11.30 and 2.30 and before 6.30 pm. We know this because two of the three women regret after Ben’s death that the pubs are not open (p. 16). Pubs in England were only able to open between 11.30 and 2.30 (3 pm in some areas) and from 6.30 until 11pm due to the licensing laws which operated between1914 and their repeal in 1988. Mrs Nattle has been sure to catch the lunchtime opening hours between 11.30 am and 2.30 pm to take her small whisky because as she tells us she went to look for Mrs Dorbell in ‘the Dook of Gloucester’ (pp.3-4), only to find her uncharacteristically absent. Thus after Ben has ‘died’, Mrs Nattle wishes it was after opening time: ‘I wish they wus open. I could just do wi’ one: my throat’s as dry as a bone’ (p.16). Mrs Nattle sees no irony in her simile though she has just commissioned the sudden change of Ben from living body to skeleton-in-waiting. Mrs Nattle charitably offers to sell her a nip of her gin (though earlier Mrs Dorbel has expressed her private view of Mrs Nattle’s ‘rot-gut: ‘Tcha! Methylated spirits’, p.3) . The apparently unoccupied room is presumably dimly lit then because of Hanky Park’s constant industrial smog, and also because that subdued light sets the right atmosphere for the play’s dark deeds. Thus the ‘To open’ lighting instructions apply only to the very opening when no characters apart from, as it were, Ben are on stage. My feeling is that this state of gloom might be held for some time, with just the glow of the fire, the blue floods through door and window, and the blue section floats inviting the audience to peer into the set and make what sense of it they can, including the relationship between the lighting, the set layout and the sound effect from the screened bed-stead: ‘a vague sound suggestive of laboured breathing’.

The second lighting state presumably is then held for the rest of the play. Though the Lighting Plot specifies that ‘AT CUE (Mrs Dorbell lights gas)’, there is no indication that I can see of what that cue is. It seems likely that on her entrance from the street she anxiously goes first to see if Ben is dead yet in the blue light, and perhaps only lights the gas (for which I would have expected a stage direction) when she says ‘Let’s see where ah’m up to’ (p.2). Thereafter the lighting is adjusted to the living rather than the dying, and all the action and dialogue of the play which takes place both centres on Ben and wholly ignores him. Being unconscious, he is there and not there, while one, two and then three older women debate his end and means. I assume that the various blue light effects remained in place to give a sense of the gloomy outside while the interior is lit (perhaps not very brightly) by the perch lamps to each side of the proscenium arch, and by the front arcs which focus on the table where most of the play’s conversations take place, though there is also a point where Mrs Haddock stands after her entrance to the house, and all three presumably stand and move about the room once Ben is dead. Overall, the impression might be given of a gas-lit house with plenty of shadowy areas against the background of an even gloomier exterior.

5. The Adaptation

A short story can work in ways which a play cannot, and vice-versa. Many of the adaptation decisions made by Gow and Greenwood for the play of Love on the Dole started with reducing the number of locations in the novel so that most of the narrative could be staged within the Hardcastle’s house (Act I and Act III, Scenes 1 and 2) – though it exceeds the simplest adaptation decisions by having one outdoor scene on the moors (Act II, Scene 2), regarded as having a spectacular set by some reviewers, and one urban outdoor scene (Act II, Scene 1), set at night in an alley and under the railway arches and therefore involving a set-change and indeed quite a spectacular street set. The Practised Hand similarly reduces the locations of the short story, but is more austere in relocating all the narrative into the interior of Mrs Dorbell’s ground-floor, a more suitable technique for a one-act play. In the short story are the following places, easily constructed in prose, of course, through description of environments and narrative about the movements of characters, something not so easy in a drama which is largely though not wholly done through physical representation:

- the street outside the Duke of Gloucester pub

- the interior of the pub (the ‘ladies room’)

- Consort Road runnig between the pub and Mrs Haddock’s house

- Mrs Haddock’s house (kitchen)

- Mrs Dorbell’s house (ground floor)

- Mrs Dorbell’s house (upstairs, Ben the lodger’s back bedroom)

- Mrs Dorbell’s kitchen

Greenwood skilfully adapts the narrative so that it can all be told / enacted from within Mrs Dorbell’s kitchen, which therefore has also to be Ben’s sleeping quarters.

In terms of the ‘sordid’, neglected and poverty-stricken nature of Mrs Dorbell’s house this practical decision also makes very good thematic and atmospheric sense: Ben suffers and dies while Mrs Dorbell and her acquaintances get on with their ‘normal’ life. Instead of Mrs Dorbell going out to the pub as usual on a pension day , Mrs Nattle has to come and find her, allegedly ‘worried’ about this change in her habits. Similarly, instead of Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle going to Mrs Haddock’s house to ask for her ‘expert’ advice, she must come to visit Mrs Dorbell’s residence to see Ben and to use her ‘practised hand’ if appropriate. Ben’s presence on stage throughout the other characters’ conversations is an adaptation change with large effects: though he is not obviously conscious, nevertheless the dialogues about how slowly he is dying and if things could be speeded up a bit take place in his living presence, as the audience is constantly reminded by the acting out of the stage direction that there should be ‘a vague sound, suggestive of laboured breathing’. No actor is named as playing Ben, so perhaps some mechanical device was used for this macabre and constant (up to a certain point) sound-effect (unless a stage-hand was deputed to lay down for the thirty-minute duration of the play and provide the sound-effects?). Mrs Dorbell comments heartlessly that his breathing is ‘like a h’engine’ (p.6).

In addition to these larger narrative changes, the play version also has some lines not present in the same form in the short story, not always because they are essential alterations but presumably simply because Greenwood is revisiting and reworking earlier material and cannot help some new inventiveness. Since the important topic of drinking (important to Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle, anyway) manifests itself in a new place and sequence, the playscript adds some new business and dialogue about how Mrs Dorbell conceals her habits from Mrs Nattle so as not to have to share her precious half-bottle of whisky with her. Alone (apart from Ben), Mrs Dorbell laments the amount of her pension which she has just drawn and that though she not yet bought any food at all, she has of her ten shillings a week ‘on’y nine and fourpence left’. This is based on some thoughts she has in the story in the pub but adapts it to her solitary drinking at home:

How do they expect a body to live? Ahhh! (she smacks her lips as she lovingly and carefully puts a small bottle on the table). It’s worth it, even though they do charge y’ eightpence for half a noggin. And ah don’t see why I shouldn’t. (p.2)

This sets up a new piece of stage business when Mrs Nattle calls at the front door:

(with surprising agility Mrs Dorbell recorks the bottle and whisks it into the table drawer. Then she composes her hands on her lap and assumes an expression of bleak innocence), p.3.

This in turn contributes to some grim comedy once Mrs Nattle has made her entrance and first speech, and also allows Mrs Dorbell to broach her problem in a way which makes it clear that it is from her perspective she who is suffering most from Ben’s long illness. Mrs Nattle tells Mrs Dorbell that the bar-man at the Duke of Gloucester has suggested she must be ill if she is not there for her usual pension-day whisky. Mrs Dorbell builds on this opening to tell of her pitiful state – in fact so miserable is her situation that she has become teetotal!:

Mrs Dorbell: (Gloomily). I aint bin in no mood for it, Mrs Nakkle. Last drop I had was in your house and, when I supped it, I sez to meself: ‘Y’ don’t have no more, Nancy Dorbell.’ That was the last of the Mohamicans. And not a drop ‘as touched me lips from this day to this (p.4).

In the joint perspective of these two (somewhat untrusting) ‘neighbours’ what deeper indicator of utter depression could there be than giving up drink? The confused / malapropistic reference to James Fenimore Cooper’s famous novel, The Last of the Mohicans (1826) gives a comic touch (Mrs Dorbell may be confusing the native American people with the incorrect term ‘mohammedans’, which has a certain relevance to not drinking alcohol). However, perhaps the main effect of the speech is to show off Mrs Dorbell’s self-dramatising rhetoric, which she uses to assert her simultaneous ‘victimhood’ at the hands of Ben and her alleged grief at his long suffering. Mrs Nattle does not for a minute believe in this renunciation and sniffs the room for any aroma of whisky (later, while Mrs Nattle goes off stage to fetch Mrs Haddock, Mrs Dorbell downs the rest of the bottle to make quite sure she won’t have to share it with Mrs Nattle!, p.8). Nevertheless her alleged renunciation of the demon drink means Mrs Dorbell can then easily move conversation on to her great worry about Ben’s long dying and the harm it is doing her. The drink motif is picked up again with out any hesitation about teetotalism and abstention after Ben has so suddenly ‘died’ during Mrs Haddock’s visit, when Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle agree they ‘both deserve’ a drink (p. 16).

There are three other noticeable differences from the story version, two shocking, and one surprising in that it perhaps restores some dignity to Ben’s death. In the story Mrs Haddock’s method for ‘helping’ the dying remains more or less her secret, but here she explains it in more detail to Mrs Nattle who tells Mrs Haddock that in future she could assist her. However, once Mrs Haddock has been paid her fee and departed, Mrs Nattle tells Mrs Dorbell that ‘I don’t recommend no more: I set up in business for meself in future’ (p.16). While murder by a medically qualified person is no different from murder by a layperson apart of course from the additional betrayal of trust, there is something utterly shocking in Mrs Nattle’s easy assumption that she could help people into the next life just as well herself, for a ten shilling fee, of course. Secondly, the play introduces a song which Mrs Nattle sings while the three women await Ben’s expected death. This is ‘inspired’ by Mrs Dorbell’s response to Mrs Haddock’s suggestion about which undertaker to use to bury Ben (Mrs H is on commission to one, of course) that the Parish can bury him as a pauper. This material is in the story as well, and in fact at greater length, but there is no hint of the song which Mrs Nattle sings so unexpectedly as commentary on Ben’s funeral arrangements. Here is the play dialogue about paying for the burial, the song itself and the sound which signals that Ben has breathed his last:

MRS HADDOCK: Who’re y’ going t’ get to bury him? . . . if y’ take my tip, y’ll go along to Mr Fogley . . .

MRS DORBELL: (With supreme astonishment). Undertaker! Undertaker! Why, d’y think I’m payin’ for t’ funeral? No, no! I’m not made o’ money. Poooh! Let parish bury him! He’s cost me enough already.

MRS HADDOCK: But what about th’ insurance?

MRS DORBELL: Th’ insurance? I paid that. Scraped and saved this last twelve year: aye debarred meself many a luxury. No fear, that’s to be set agen me old age.

MRS NATTLE: Aye, th’ old song’s right:

(Singing)

It’s the same the whole world over

It’s the poor what helps the blind,

It’s the rich what gets the pleasuare

It is . . . . [sic in text]

(A sound from the bed interrupts the song: the three women rush to the curtain).

MRS HADDOCK: (Pulling curtain aside). He’s a josser.

MRS DORBELL (Weeping). Poor owld Ben, Poor owld Ben. (pp, 13-14).

Mrs Dorbell’s ‘debarred meself’ is another malapropism, where she perhaps intends ‘denied’, but maybe the ‘debarred’ verb also comically suggests she (allegedly) denied her self time at the bar. Her rationale for not putting aside some of the insurance death benefit for Ben’s funeral is that it came from her sacrifice and that she will use it to survive into old age (something which Ben of course does not). Mrs Nattle’s song appears to be intended as traditional wisdom backing up the legitimacy of Mrs Dorbell’s thinking and her perspective. However, the match between song lyrics and Mrs Dorbell’s situation seems a little loose. She may (perhaps) be poor, but we have not seen her ‘help the blind’ or more generally the sick, but rather help herself. It might be said that she is rather, having gained the death benefit, to be identified (if only temporarily) with the rich who get the pleasure (I take it that ‘plesuare’ [sic] in the play typescript is intended to give a sense of how the song word syllables are sung to the tune). In short, the song has only an ironic light to cast on Mrs Dorbel’s behaviour and self-justification. I will return to the song itself again shortly, but would first like to complete this scene in its own right, and the discussion of the remaining difference from the short story version.

Mrs Haddock’s concluding comment on her own ‘handiwork’ seems especially heartless and disrespectful in its use of a slang word, even if it is an unusual one. I took it to mean from the context ‘a dead man’, ‘a corpse’, but the OED does not give this as either of the word’s two main senses, both dating only from the 1880s:

- a member of the clergy or minister of religion. Australian.

- a. a simpleton, a soft or silly fellow. So, in flippant or contemptuous use, a fellow, an (old) chap.

Ignoring the exclusively Australian usage, I think we might conclude that Mrs Haddock’s intention in her use of the word is indeed contemptuous, seeing Ben as ‘silly’, someone who has let himself be triumphed over or manipulated, who has come out of things the worse. Given that Mrs Haddock has killed him, and that he could do nothing whatever to save himself, this contempt is shocking and inhuman indeed. OED agrees that it is an infrequently used word and gives its etymology as deriving from a word of Dutch origin used in the Far East from the early 18th century on, and especially China, joss, which indicated ‘a statue or figurine depicting a god or other important figure’ (the same sense occurs in ‘joss-stick’). Presumably, a sense of a ‘small figurine’ transformed to something like ‘a puppet’ to give josser its meaning of a negligible fellow, a simpleton, and I am told that the word persists in Mancunian where it indeed still means a fool or simpleton. It seems cruel to see dying as an act of foolishness (it comes to us all). Mrs Haddock’s colloquial response to Ben’s death apparently contrasts sharply with Mrs Dorbell’s outpouring of grief, except that given our already established sense of her selfishness, we can see that ironically this is just an additional way of using Ben as a puppet, having first commissioned his death and of now hypocritically turning attention back to herself as chief mourner. Greenwood’s irony here is supreme.

Next comes the final change I can see from the short story. There Mrs Haddock and the other two women quickly lay Ben out themselves:

Let’s get him laid out and comfortable . . . he’d better have a smile on his face’, said Mrs Haddock, picking up the pillow, shaking it and placing it under Ben’s head. The two women watched Mrs Haddock push up the extremities of Ben’s mouth. ‘It sets like that when he gets cold.’ she explained (p.209).

The comment about making him comfortable seems sheer hypocrisy, given how Mrs Haddock killed Ben, but I assume that the main reason for making him look respectable and with the pillow under his head is to remove any obvious evidence of foul play, and so likewise the posthumous smile is more about appearances than about the dignity of the deceased. I generally think that if anything the play is more brutal than the story and yet its material on how Ben needs to be properly laid out seems contradictory. Here is what Mrs Haddock says in the play version immediately after Mrs Dorbell has wept at Ben’s death:

MRS HADDOCK: (In business-like tones). Y’d better get Mrs Bull in to lay him out. put kekkle on, she’ll want hot water . . . Aye, and y’d better tell Mrs Bull quick. She allus likes to see that they’ve a smile on their faces and y’can’t put one on when they’ve gone cold. (Informatively). She just pushes th’ end o’ their mouth up and it sets (she pushes the ends of her own mouth up and, retaining the expression, looks at Mrs Nattle) like that (p.14).

This certainly fulfils some reviews’ descriptions of the play as having ‘grim’ and ghoulish’ elements, as the living Mrs Haddock imitates the artificial smile imposed on the dead, which implies that they were happy at their ends, even if not in their lives. However, it seems to run counter to Mrs Dorbell’s desire to maximise the amount of the death benefit which goes to in her view to the most deserving party – for Mrs Bull will surely want her customary fee for laying out. Perhaps this is also about sustaining an appearance of normality for it is customary for Mrs Bull lays out all the dead of Hanky Park in her capacity as ‘handywoman’. However, it might also be connected to Mrs Haddock’s status as a ‘certified midwife’ (much less stressed in the play than in the story), for midwives were absolutely not meant to lay out the dead for fear of cross-infection to babies and their mothers (whereas the traditional handywoman like Mrs Bull had felt no hesitation in dealing with birth and death). Of course a deep irony is that Mrs Haddock has just had a closer engagement with death than ever Mrs Bull did (for fuller discussion of the legislation on midwives and handywomen and their functions see ‘Call the Handywoman!’: Birth and Death in Hanky Park (1933-1937) *).

6. Mrs Nattle’s Song: ‘It’s the Same the Whole World Over’

The song itself was one with considerable popularity in the thirties and after though it did not have a long history. It was known under two titles, one derived from the main verses, the other from the repeated refrain. The title derived from the main verse lyrics was ‘She Was Poor but She was Honest’, while the title derived from the refrain is the one Greenwood uses as the subtitle of The Cleft Stick collection, ‘It’s the Same the Whole World Over’. There are variations on the lyrics but the narrative looks like a traditional folk-song theme of a country-girl who is seduced and abandoned by a wealthy ‘gentleman’. The tune also feels as if it might have a folk-song origin, but it is generally agreed that it has named writers and was created mainly for music-hall performance in 1930, though one source says it was based on a traditional song. The music is said to be by Bert Lee (1880-1946), and the words jointly by Lee and R.P. Weston (1878-1936), who collaborated on hundreds of successful popular songs. The Folk-Song and Music-Hall.com website gives this version of the first two verses and the refrain, in which in the verses lines two and four rhyme and then lines six and eight, while in the refrain lines two and four rhyme:

She was poor but she was honest,

though she came from ‘umble stock,

And her honest heart was beating

Underneath her tattered frock.

But the rich man saw her beauty,

She knew not his base design,

And he took her to a hotel

And bought her a small port wine.

It’s the same the whole world over,

It’s the poor what gets the blame,

It’s the rich what gets the pleasure,

Isn’t it a blooming shame?

In the rich man’s arms she fluttered

Like a bird with a broken wing,

But he loved her and he left her,

Now she hasn’t got no ring.

Time has flown – outcast and homeless

In the street she stands and says,

While the snowflakes fall around her,

‘Won’t you buy my bootlaces.’

Information about the song is derived from a number of web-sites, listed in the end-note (1). There is general agreement too that the song was popularised and became a hit in the performances of the very well-known music-hall singer Billy Bennett (1887-1942), for whom it may have been specifically written. He recorded it on a Columbia record (DB164) in 1930 and for a Regal Zonophone disc (MR147) again in 1932: both recordings are available on YouTube, but I think the later recording has a far better acoustic and better (i.e. in tune!) singing especially of the refrain by a chorus, so will use that one. This is an extract of the first verse and the refrain, though in fact the whole side of the record only has room for two verses and the repeated refrain: https://youtube.com/clip/UgkxeS5Y1QXjxmO4Y6Bb-gg6pz7s0zs1Txkn?si=XUeiRpk806PK8OEv (as usual the clip is on a loop, so just click back to this site when you have listened enough; 0.46 seconds gratefully clipped from the Vintage British Comedy channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_DQLkccZ5uo). Though Billy Bennet was known for comic songs this song is clearly not comic and while his style may seem suited to the comic, the fate of the working-class young-woman is treated by him seriously.

The lyrics Bennett sings are identical to those given above, but the reader may have noticed that Mrs Dorbell’s short rendition of the refrain has some differences. Her second line has ‘it’s the poor what help the blind’ in place of ‘it’s the poor what gets the blame’. This may be a joke along the lines of a malapropism in that Mrs Nattle can’t correctly reproduce the words of this well-known song, and may set up some curiosity in the audience about how she is going to make the rhyme in the fourth line work with ‘blind’ instead of ‘blame’. She is luckily saved by interruption. Perhaps this mistake underlines the fact that this song does not match the actual situation it is meant to comment on. A further irony may be that while the song is about the exploitation of young women by older men, in this instance an old man is being (more unusually) exploited by three older women.

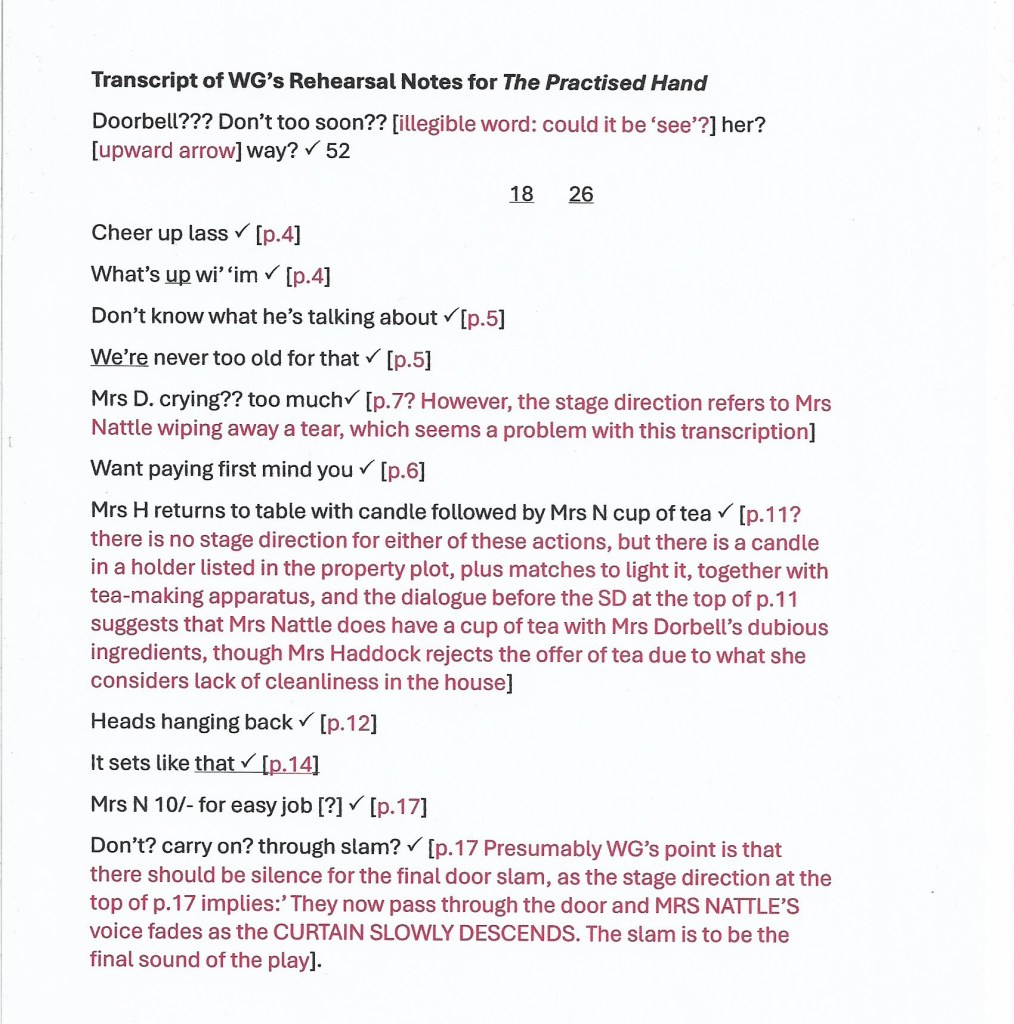

7. Walter Greenwood’s Rehearsal Notes

Now I generally maintain that Greenwood had a clear and legible hand, but these notes are more challenging than most examples of his handwriting I have seen, perhaps because they are in pencil, perhaps because they were written hurriedly during a rehearsal or performance? I have mainly managed the notes, though there are a number of uncertainties. My typed transcript is added below. Everything in black font is a reproduction as best I can of Greenwood’s words and signs, while my commentary and best guesses at uncertain portions of transcription are indicated in the red-brown font, as is my addition of the page-number of the typescript where the line or other stage business is to be found, or in some cases probably found. The ticks are of course Greenwood’s and presumably imply that he now considers this issue addressed, at least.

The majority of the notes refer to specific spoken lines in the typescript text and so were fairly easy to transcribe with reasonable confidence (though the lines are not always exactly as printed). More challenging were the references to stage business, especially as these did not always seem to refer to the actual printed stage directions. These include Greenwood’s first note about ‘Dorbell’, a second note starting ‘Mrs D’, the note about the actions of Mrs H and Mrs N, and the final note about the end of the play. I am reasonably confident that my interpretations are broadly right, though the reference to Mrs Dorbell crying (?) on p. 7 is puzzling, as is the first note where I sadly cannot figure out what the verb is (though I speculate that the intention is about Mrs Dorbell at her first entrance not being distinctly seen in the best-lit part of the stage ‘too soon’). I have not been able so far to make any sense of the numbers early on – they are not page numbers and do not seem to make any sense as hypothetical line-numbers either.

I think we can conclude from the notes that Greenwood took a close interest during rehearsal of both how lines were spoken and whether stage business did what he thought it should. In the notes on lines I take it that his underlining of words indicate that he thought this was the emphasis should fall, and perhaps imply that he thought the current speaking of the lines by the actresses was not quite what he had anticipated. Equally, his attention to stage business suggests that what is happening at present does not seem to him effective, or perhaps even that he is seeing some lacks in his own stage directions. It would be fascinating had any documents like these survived from the rehearsal process for Love on the Dole too, but still additions to the typescript are invaluable in getting an even better sense of The Practised Hand on stage. The most famous final door-slam in theatre is that at the end of Ibsen’s The Doll’s House (1879), when the wife Nora leaves her husband’s home and by implication the whole patriarchal system. Here perhaps instead the door slam indicates Ben’s ironic complete and undisturbed temporary possession of the house, though it will do him no good, while Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle go out to claim their wordly ‘inheritance’.

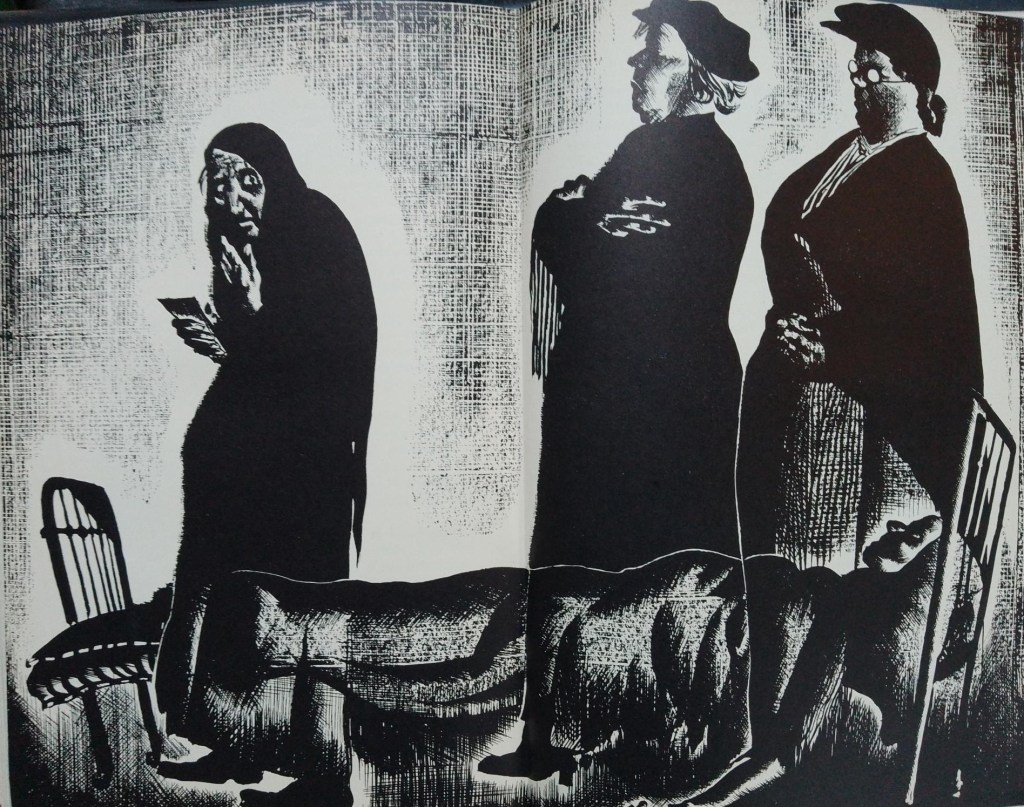

8. Arthur Wragg’s Rehearsal Sketches

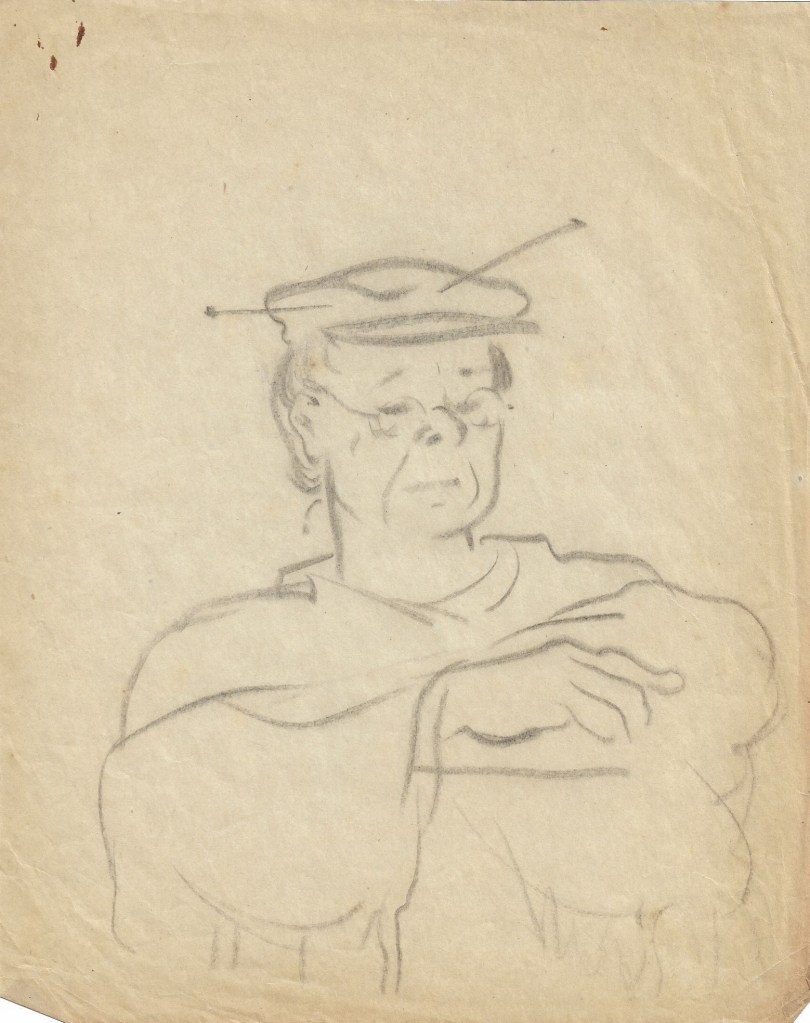

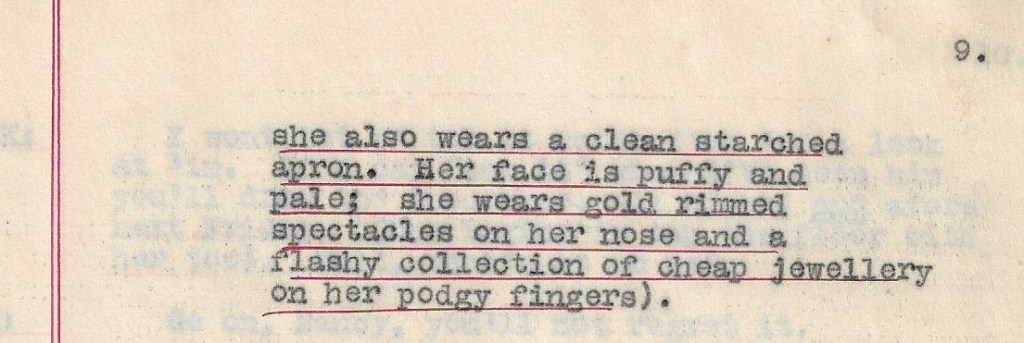

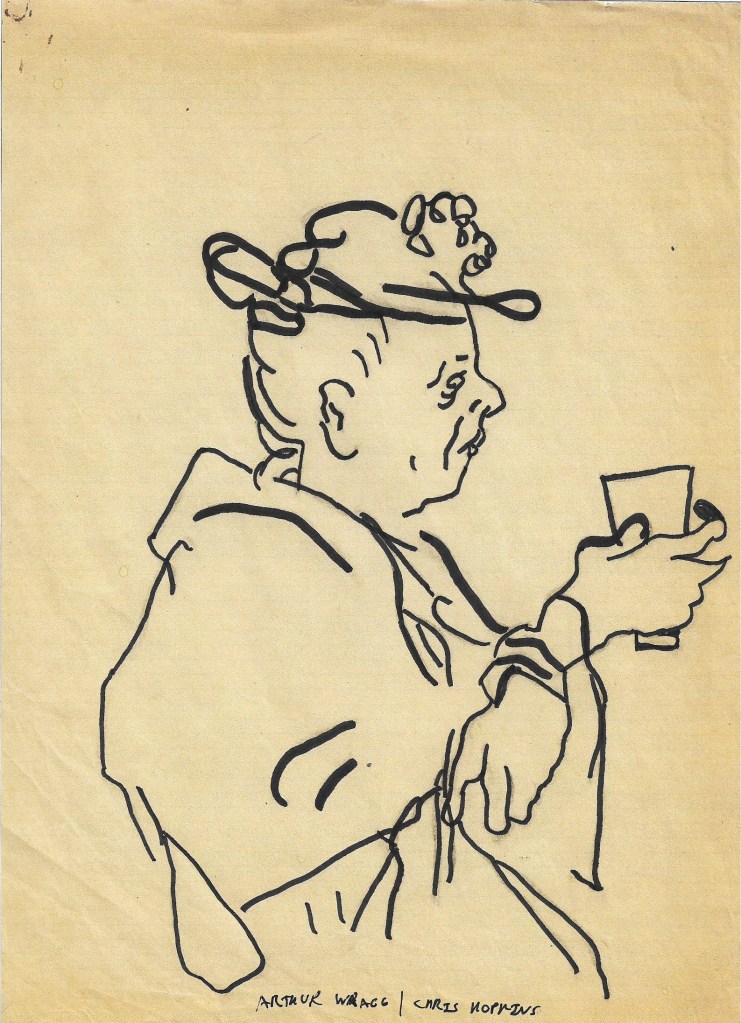

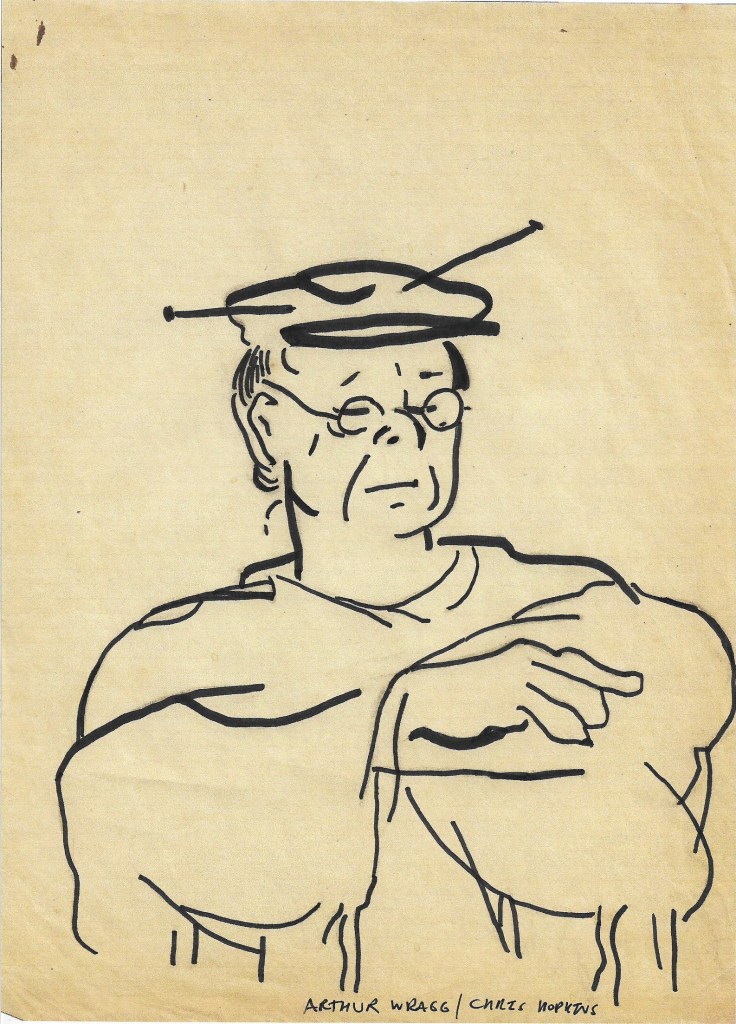

Finally in our loose-leaf insertions in the typescript are perhaps the two most surprising and indeed extraordinary finds. While the other leaves are wonderful, they are what one might expect in a production and rehearsal process. But sketches by a celebrated artist of two of the characters in costume and in their parts is surely not so usual. Each of the sketches is on a piece of remarkably thin cream/ivory cartridge paper (or at least it is cream/ivory in tone now), measuring 8 inches x 10 inches (21 cms x 26 cms). The sketches are both in pencil and are unsigned.

Mrs Nattle (I believe)

Mrs Haddock, undoubtedly. Both sketches scanned by the Author from the originals.

The Burwood Books description identifies the two sketches as ‘likely to be Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Haddock’. In fact, while I agree that the second pictured above is Mrs Haddock, I think that the first is Mrs Nattle, Mrs Dorbell’s friend (?) and helper (?), partly because the featured cup of tea links her to the stage business described above when Mrs Nattle helps herself at Mrs Dorbell’s invitation to what is, after all, a free cup of tea. However, the two sketches are not wholly without puzzling aspects. At her first entrance Mrs Dorbell’s clothes are described thus:

Clearly, her dress signals poverty and wretchedness, though as we learn during the play she perhaps spends some income on what are for her competing priorities. The description does not closely match Wragg’s sketch. While the shawl is there as the main piece of clothing, no hat is described and in the sketch this is a dominating characteristic.

At her first entrance a page later, Mrs Nattle’s costume is also described, but it also makes no mention of a hat – let alone one with a prominent flower adornment at the front:

However, the two descriptions do make clear a certain hierarchy across the two characters – while both wear the typical clothes of a poor working-class woman in Hanky Park, Mrs Nattle seems to carry herself with more alertness to opportunity and indeed with potential authority. Of course, it is notable that what we do not have is a third sketch of Mrs Dorbell with which to compare her friend. What we do have are the descriptions of their dress in the short story version, which are closely related to these stage descriptions but with some additional details which confirm the contrast I have outlined. Here is the description of Mrs Dorbell on the first page of the story (p.194):

This confirms the poverty and/or inattention to dress, as well as the lack of cleanliness. The ‘grime of Salford’ merges all her clothes into one, and perhaps it is implied that she too is inseparable from her literal and metaphorical environment. Her ‘perpetual lugubriousness’ is presumably an expression of her sustained attention to what she feels she lacks and believes she should have. The story description of Mrs Nattle is more concise and closer to that in the play, though with one significant expansion: ‘she was Mrs Dorbell’s counterpart so far as dress was concerned, but she differed from Mrs Dorbell in that she carried herself stiffly after the manner of one accustomed to give orders and to be obeyed’ (pp.195-6). However, still no hat. I do not think Wragg would have added such a significant feature without warrant and my assumption is that in the staging of the play it was decided that Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle needed to be more firmly distinguished and perhaps too the (relative) social superiority of the latter signed by her possession of a flowered hat. I think the firm facial expression given by Wragg to Mrs Nattle nicely picks up her habits of command and control.

The play describes Mrs Haddock at her first entrance thus (pp.8-9):

There are clearly some clothing/costuming differences which distinguish her from both Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle and give her top place in the hierarchy. Mrs Haddock has the possession of a proper dress, in place of their ‘bodices’, which according to OED can be inner or outer garments, but are probably worn by two of our principals for informal comfort and ease of maintenance (if any), and perhaps as clothes which were more fashionable in their younger days. The dress is ankle-length suggesting a contrasting respectability, and since it is not described as ‘stained’ is presumably clean, which seems to be especially backed up by the specifically ‘clean starched apron’. Her gold-rimmed spectacles surely add another layer of both respectability and relative wealth, as does if only up to a point her ‘flashy collection of cheap jewellery’. Presumably the jewellery impresses her clients if they are like Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle, but not any observer who knows anything about jewellery and/or conventional taste. I am not sure what her face signifies – is she pale because she spends much time indoors, which might be a kind of status-marker, but ‘puffy’ because she does not go short of food nor alcoholic drink?

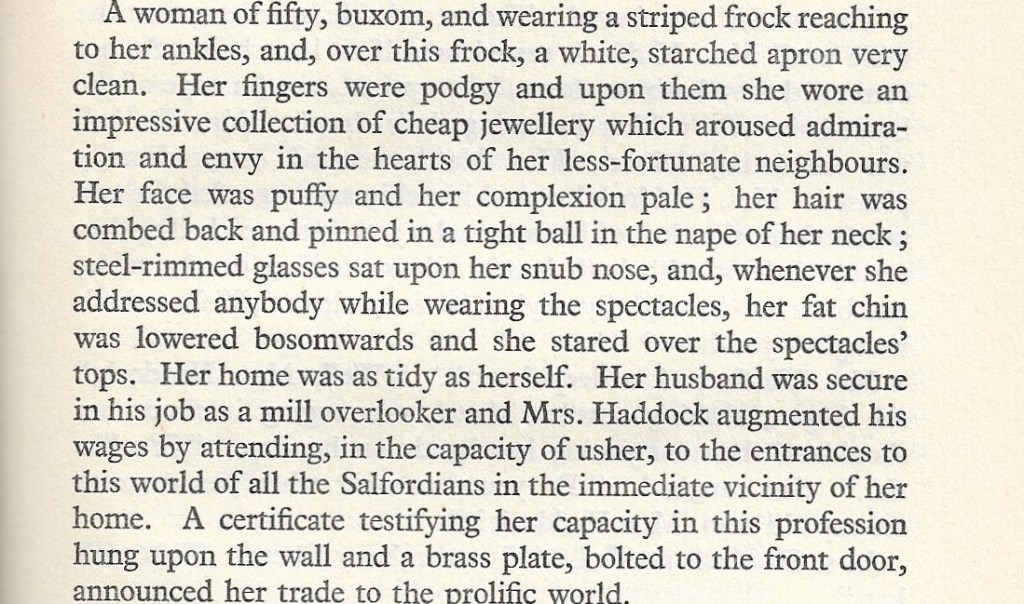

Her description in the story version is very similar but expands a few points with the relative leisure given by prose:

The dress, or frock is there, as is the very clean white apron, and the ‘impressive collection of cheap jewellery which aroused envy in the hearts of her less-fortunate neighbours’. The gold-rimmed spectacles are however here only ‘steel-rimmed’. We also see her in her home context, something the play cannot do with its sole setting in Mrs Nattle’s house, and which bears witness to her love of tidiness and secure status, including her status as certificated midwife (of course as we see, moral tidiness or order concerns her less). Again what we do not have here is any sign of a hat – even when Mrs Haddock goes out to see Ben in his lodgings. Again, I assume that Mrs Haddock’s hat was added as a part of her stage costume and characterisation, though its style is not what I would have expected. Perhaps the hats were staging details suggested by Reginald Bach? (though Greenwood would I think have had to approve). Presumably the hatless Mrs Nattle is under this hat hierarchy necessarily ranked lowest.

Wragg’s sketch captures the gold-rimmed spectacles but actually none of the other dress features in the stage description appear in his drawing: no striped dress, no white apron, no jewellery, but instead an all-enveloping shawl for outdoor wear, just like those worn by Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle (though let us imagine it as cleaner than the first such shawl, at least). Her hat is not adorned with a flower but seems instead to be a man’s cap, though it is kept very tidily and firmly in place with two terrifyingly long hat-pins. These must surely also have been worn by Lucy Evelyn as she played the role of Mrs Haddock, and naturally Wragg worked from what he saw on stage rather than from the written description. Perhaps masculine cap and sharp hat-pins suggested a suitably ruthless determination in her character?

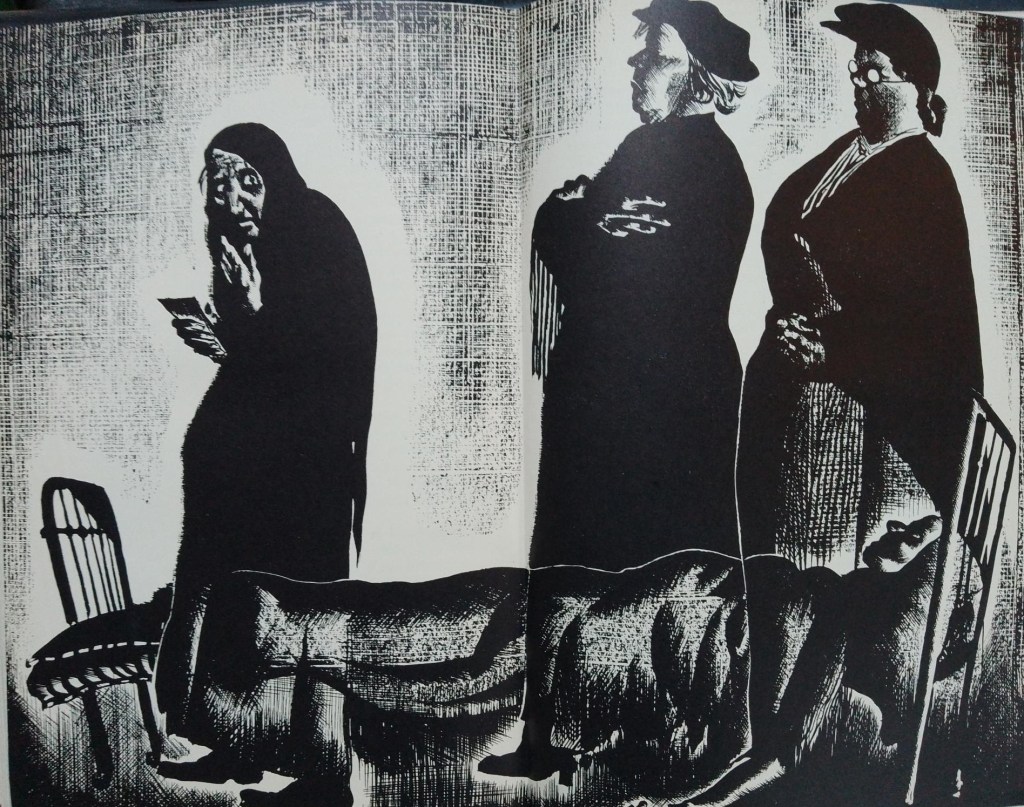

I have the advantage of knowing very well the illustration Wragg did for The Cleft Stick version of the short story, and which I think he likely developed from these sketches – though there are certainly differences – and of course he had to start Mrs Dorbell from scratch (perhaps this sketch is simply missing, but I think it more likely that in a half-hour run through of the play Wragg might not have had a chance to complete three sketches). The completed picture for The Cleft Stick collection story will almost inevitably suggest itself as the end-point and final form of these two sketches and perhaps that is right – but the two sketches may stand in their own rights as well as contributing much to our understanding of the process by which Wragg got to his superb rendition of the three sinister women. Here it is:

I have discussed this illustration before (see Walter Greenwood’s Two Manchester Hospital Stories (1935 and 1945) *) so here will focus mainly on similarities and differences to the two sketches. First, of course, the two sketches are separate character studies, and rather than being full-length are half-length portraits. Each also has a different orientation to the ensemble drawing, where Mrs Nattle and Mrs Haddock both appear in left profile, looking towards Mrs Dorbell’s face-on / turned to the right orientation: in her sketch Mrs Nattle appears in right profile, while in hers Mrs Haddock appears almost face on, but with a slight turn of the head to the right. This is no doubt partly a consequence of the depiction in the story drawing of a dramatic moment involving all three characters in which their gazes express relationships, or anyway lines of force, between the three, and indeed between one of them and Ben. My reading of the moment is that it is when Mrs Dorbell has to accept that Mrs Haddock can ‘help’ Ben on his way swiftly but must decide to trust her and risk pawning her pension-book in order to raise the ten shillings fee in advance (if Ben does not die quickly she will have to go without her pension for a week and hence food and drink, or rather, drink and food). It is for her a difficult decision – though not a difficult moral decision, but rather one about financial risk, which concerns her much more. She holds the crucial pension book in her hand as she ponders the decision. The arrangement of the three figures (and the three haloes of white light round each figure?) suggests that Mrs Haddock and Mrs Nattle are using moral persuasion to urge Mrs Dorbell to make her decision, but usual expectations are reversed and it is really immoral persuasion and in each case an entirely self-interested exercise of power. Mrs Nattle’s hat here is not only flowerless, but also looks much more used, with a squashed and pulled-down look. Her hair too is tousled rather than tidy. Mrs Haddock’s hat is clearly too big for her here and hence obviously not her own, while her face has become rounded and more elongated, though with a double-chin, rather than square.

I think the sketches probably also capture particular moments in the play’s drama, but since they are individual and separate they do not so clearly convey the dramatic interactions of the book illustration. I take it that the sketch of Mrs Nattle shows her taking her cup of tea as she quizzes Mrs Haddock about how exactly you help someone like Ben who is slow to die (typescript pp.10-11), while the sketch of Mrs Haddock with her arms folded and eyes shut may show her making it clear for the second time to Mrs Dorbell that she has to be paid in advance for her services: ‘And there wont be no performin’ till you get back wi’ the ten bob’ (p.10). Mrs Nattle’s folded arms and Mrs Haddock’s hands folded across her stomach in the story illustration of a similar moment may well have their origins in the second sketch.

Wragg has clearly altered his mind about some details from the sketches to the book illustration – no flower for Mrs Nattle’s hat (perhaps it made her too respectable or feminine?), and no hat-pins for Mrs Haddock (perhaps these made her look too eccentric when she should look superficially respectable?), though she retains her man’s cap. She also keeps her shawl but it is open to show what is surely her trade-mark striped dress, though no starched apron. Her spectacles which in the sketch show her closed eyes behind the lenses are here finished with one of the few areas of pure white in the drawing, ironically suggesting not innocence but the terror of her blank and unreadable gaze. Of course, the finished nature of the illustration gives it different characteristics from the sketches: while the sketches are outline drawings only, enabling speed and immediacy in Wragg’s rendering of what he saw on stage, the illustration is done after reflection and with less of a time-constraint, and finished with characteristic subtle hatching in the background (probably in this case produced by scratching lines through a layer of back ink) and with thick black ink washes to depict the majority of the clothing of all three women conspirators. One notable feature of the illustration which I think may reimagine an effect from the play for this new medium is the depiction of Ben the lodger. In the play he is a constant presence/absence and Wragg echoes this marginal state of being in his drawing, which shows a human being who is already barely there, ghostly and apparently semi-transparent. In a literal sense we can see the shoes of Mrs Dorbell and Mrs Nattle underneath the iron bedstead because of its very inadequate bedding, but we also seem to be able to see though Ben to Mrs Dorbell’s skirt and Mrs Nattle’s skirt and legs due to some suggestive vertical lines in the drawing.

The sketches are really finished: they had done their job in capturing quickly the characters and costumes (and I suspect too likenesses of Minnie Watersford, Marion Hine, and Lucy Evelyn) which Wragg could then work up into a finished illustration. Nevertheless, it might be satisfying to see what they might have looked like had the artist gone on to his usual next stage of adding to the drawing in pen and black ink and/or small brush and black ink (in as far as my untutored efforts can follow his work).

The two sketches with ink applied (in fact with a fine and a broad lettering pen) following Arthur Wragg’s pencil marks. The signature is, of course, not Arthur Wragg’s but indicates his authorship together with my modest contribution. I added ink strokes to print-outs of scans of the original pencil sketches, of course. Below is Wragg’s finished illustration again together with the two ink sketches, but this time flipped so the profiles are more like, and at a closer size for handier comparison of the treatments of Mrs Nattle and Mrs Haddock (the flip makes the signatures into mirror-writing).

9. Some Conclusions

My first commitment in this article was to record as exactly as possible what this unique new contribution to Greenwood (and Wragg’s) oeuvre consisted of, and then to discuss and explain what fresh knowledge it might add to our understanding of their work and collaboration. The typescript is the first / only known copy of Greenwood’s stage adaptation of his early short story ‘The Practised Hand’, which dated back to his period of unemployment between 1928 and 1931. Together with his rehearsal notes, the property and lighting plots (probably the work of the producer Reginald Bach) and Wragg’s two character sketches, the whole typescript and its associated loose-leaf pages add enormously to our knowledge of Greenwood’s only one-act play, and indeed one of his most controversial texts. It also suggests that the writer and artist were working on both the play adaptation and the volume of short stories sometime over the summer of 1935, though given the publication date of The Cleft Stick in 1937, this collaboration must have extended into 1936, especially as all of Wragg’s fifteen illustration for the book were new work – with the exception of that for ‘The Practised Hand’ for which he at least had some preliminary sketches! The whole idea of a collaboration between the two went back to a joint lunch invitation from the important Labour Party leader, Sir Stafford Cripps, as we learn from a frustratingly undated letter (Wragg almost never dated his letters) from the artist to his friend Canon Dick Sheppard ‘I like Cripps . . . for instance he got Walter Greenwood and self together to make and do a book together, and it was fixed up at his house’ (V&A Archives, Papers of Arthur Wragg’s, Box AAD/2004/8, R45). (2) The two clearly worked closely together on the short story project at Wragg’s home in Polperro, but this typescript and the sketches suggests that at some point before 1 July the artist also visited the Hulme Hippodrome to contribute to the production and rehearsal of the play.

Greenwood’s work was often characterised as grim, but its truth to reality was also usually acknowledged, as well as its tragi-comic inflections . However in the case of ‘The Practised Hand’ some reviewers felt he had passed from realism into the ‘macabre’ (Thomas Moult, Manchester Guardian review of The Cleft Stick, 12 December 1937, p.7) or even something verging on ‘Grand Guignol’ (Stage review in sentence not quoted above, 5 July 1935, p. 7). I think the play version with a dynamic drawing on constant switches between self-serving and self-pitying sentiment and utterly selfish decisions about the value of cash in hand (or drink in hand) as compared to the ‘merely’ abstract value of a human life would have worked well, and while not necessarily totally implausible also continued a sharp satirical vein in Love on the Dole in which the economic practices of Mrs Nattle are asserted to be completely mainstream: ‘conducted on very orthodox lines; to be precise, none other than those of the Bank of England’s or of any other large money-lending concerns’ (novel, p. 103). At last, with the re-emergence of this acting copy and its supporting material we can see how Greenwood transferred this realist-tragi-comic-mock-sentimental-satire about lodgers, liquor, and life-insurance onto the stage, and how Wragg developed his sympathetic social and visual understanding of the forces at work in it.

NOTES

Note 1. See the Wikipedia entry for the song (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/She_Was_Poor_but_She_Was_Honest), the Folksong and Music hall song site (https://folksongandmusichall.com/index.php/she-was-poor-but-she-was-honest/), and the wikipedia entries for the composers and performer: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bert_Lee, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._P._Weston , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Bennett_(comedian). It is the Folksong and Music Hall Song site which suggests that Lee acknowledged a traditional origin for the song, but the reference is slightly unclear – it looks as if it may be quoting a statement on a sheet-music publication of the song, but that is not certain. I have searched for a sheet-music edition of which there surely must have been one, but so far without success.

Note 2. Quoted from at further length in my article about Greenwood and Wragg for Word & Image, Vol 36, 2020 – see https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02666286.2020.1758882# .